Overview

In the early 2000s, manufacturing-intensive communities in the United States entered a period of economic upheaval that would reshape their labor markets over the next two decades. China’s dramatic rise as the world’s leading exporter of manufactured goods, abetted by receipt of Permanent Normal Trade Relations from the United States in 2000 and accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, exerted immense pressure on manufacturing in the United States and many other high-income countries.1 Entire industries—textiles, furniture, and home electronics among them—struggled to compete with surges of low-cost imports.

In the United States, the China trade shock accounts for approximately one-quarter of the decline in manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2007.2 Although the aggregate loss of U.S. manufacturing jobs attributable to China’s changing competitive position in those 7 years—approximately 1.5 million to 2 million manufacturing jobs lost—is modest relative to the overall size of the U.S. labor market, these impacts are highly geographically concentrated, meaning that they loom large in places that specialize in producing the goods in which China rapidly gained global market share.

While economists anticipated manufacturing workers in heavily China-shocked locations to encounter some difficulties in adjusting to changing labor market conditions over the course of their careers, the extent of the disruption and the slow and faltering pace of adjustment proved far more severe than expected. The economic distress brought on by the China trade shock reshaped the lives of U.S. workers and families in trade-exposed regions along multiple dimensions. Earnings for low-wage workers fell.3 Children became more likely to live in poor, single-parent households.4 And deaths of despair among working age-adults—primarily due to drug overdoses among men—increased.5

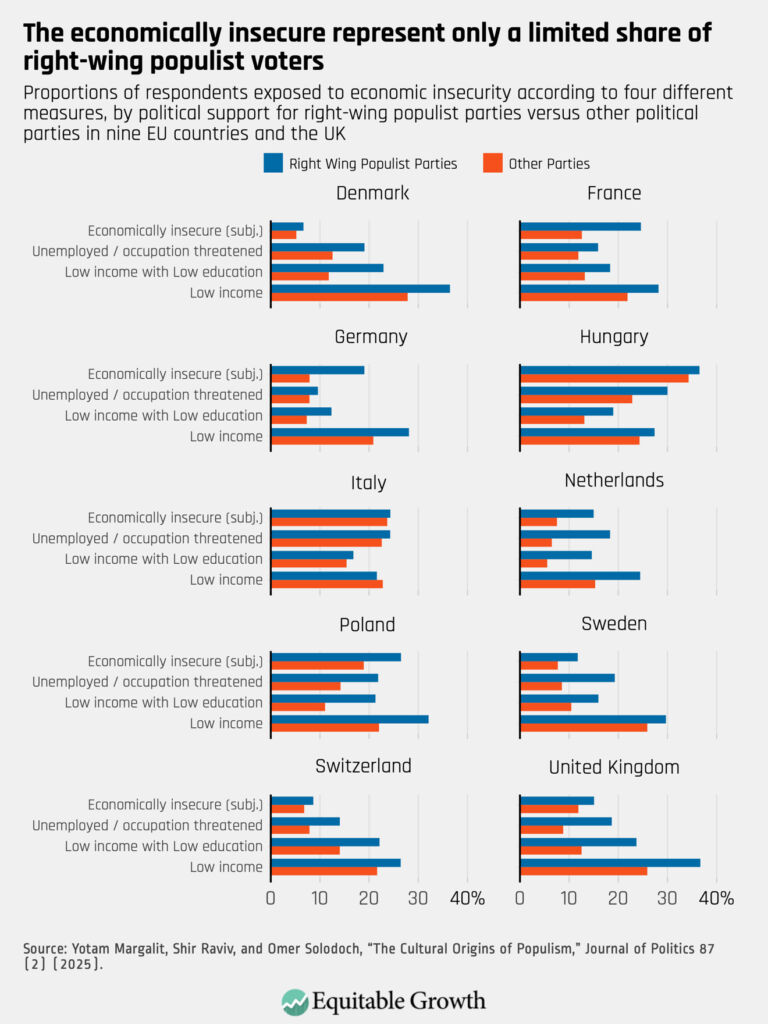

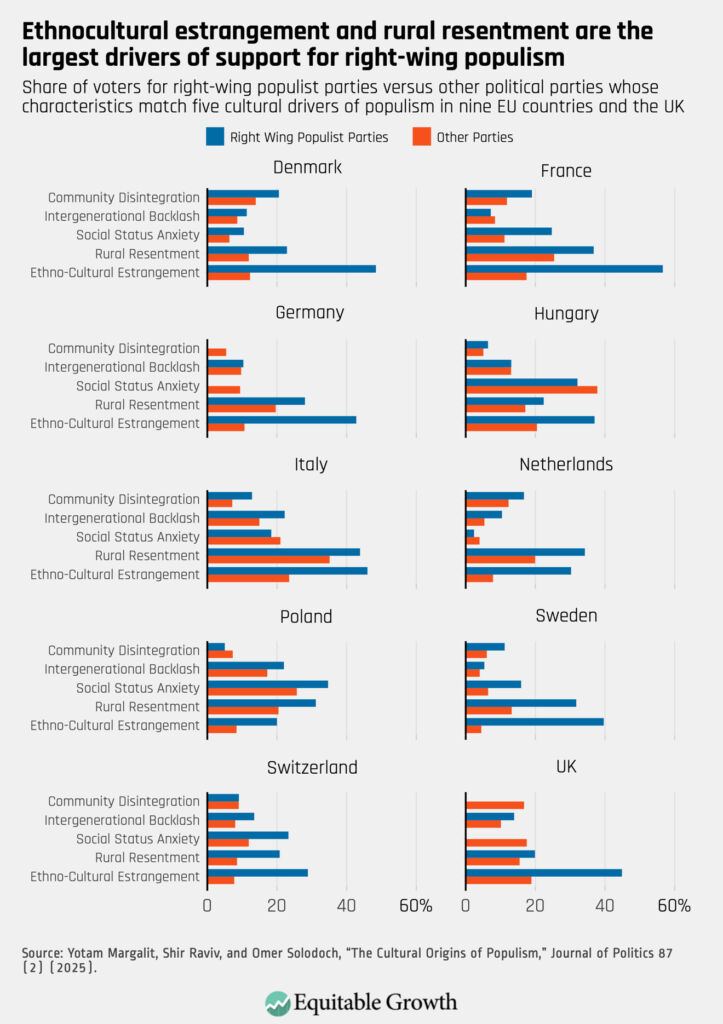

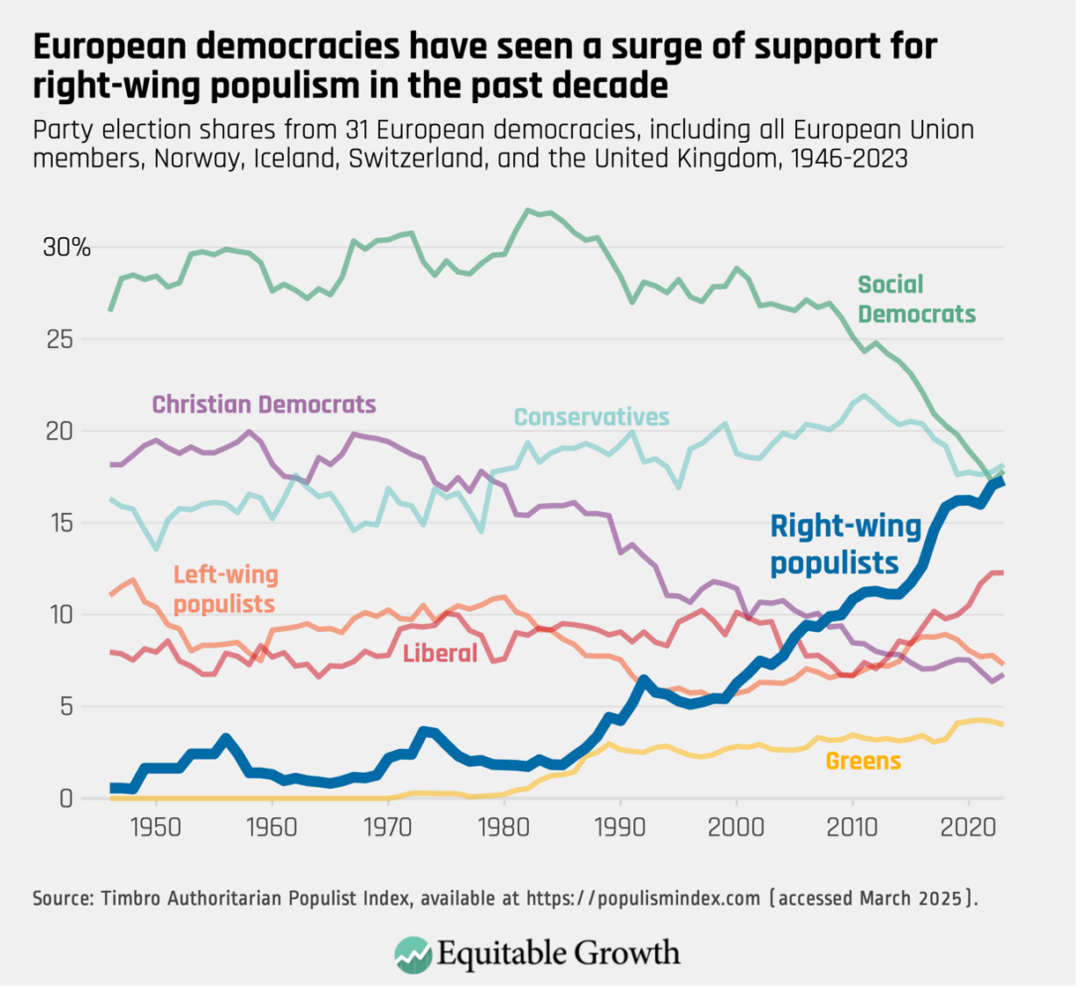

The profound economic and social consequences of the China trade shock shaped U.S. political preferences and electoral results. Across the country, trade-exposed regions became more likely to elect politicians from the right wing of the Republican party, often at the expense of moderate Democrats.6 The same trends are evident in European countries, where local exposure to Chinese import competition similarly favored nationalist and isolationist parties.7

This essay provides an empirically grounded perspective on how the China trade shock of the early 2000s shaped the evolution of trade-exposed local labor markets in the United States during the ensuing two decades, from the onset of the 21st century to the year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. Much of the extant research on the China trade shock focuses on the first decade of the 2000s, when China’s goods exports to the United States and other high-income countries surged. Chinese exports to the United States stabilized (at high levels) after approximately 2010, however, thereby affording a sufficient time window to characterize how trade-exposed local labor markets and workers adapt to changed circumstances.

Examining changes in the labor market composition of communities affected by the China trade shock alongside the evolving prospects of their incumbent workers, relative to less affected communities across the United States, provides economic context for understanding how individual experiences of globalization may contribute to the rise in right-wing populism. To provide this long-term perspective, we draw on annual worker-level data on earnings, employment, and geographic movement from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamic data, which we augment with data from several other sources.

These data facilitate two vantage points for understanding the adaptation of U.S. workers and their local labor markets to the China trade shock. The first characterizes how trade-exposed places adapted, meaning how employment, industrial structure, and earnings evolved in these locations. The second characterizes how trade-exposed people adapted, referring to paths of employment, earnings, and the geographic and sectoral mobility of workers who were employed in highly exposed labor markets in the year 2000. These two perspectives suggest distinctly different conclusions about the nature and extent of the recovery from the shock.

The first key finding of our study—and an unexpected one—from the perspective of places is that starting approximately one decade after the onset of the China trade shock in the early 2000s, trade-exposed local labor markets began to recover robustly. This recovery was enabled by the entry of a demographically distinct set of workers from the previous groups of incumbent workers. These entrants were disproportionately younger (under age 18 at the time of the shock onset), female, U.S.-born Hispanic, foreign-born non-Hispanic, and college-educated workers.

These new local labor market entrants disproportionately flowed into nonmanufacturing employment, typically into low-wage sectors with lower earnings than the manufacturing industries displaced by the China trade shock. This rapid, post-2010 transformation of the industrial and demographic structure of trade-exposed labor markets arguably reflects a manifestation of what the economist Joseph Schumpeter termed “creative destruction.”

The second key finding, from the vantage point of people, is that we find no similar worker-level dynamism. Although employment in manufacturing drops steeply and persistently in the two decades after the China trade shock, this contraction is due to the decline in workers entering manufacturing, not due to greater mobility out of manufacturing jobs by incumbent workers to other labor markets or sectors.

Indeed, only a small share of incumbent manufacturing workers moved to nonmanufacturing jobs, while another subset of these workers simply exited the labor market altogether. The majority, however, remain in manufacturing until retirement, albeit with diminished earnings growth. And opposite to the widely held expectation that incumbent workers in trade-exposed places would relocate to growing labor markets elsewhere, we instead find reduced outmigration of incumbent workers, perhaps reflecting the difficulty of relocating their households under economic duress.

Seen from the perspective of incumbent workers—particularly, U.S.-born, noncollege, White males, who are heavily overrepresented in manufacturing—the adjustment therefore looks static and largely unsuccessful, as another essay in our series also explores.8 These workers age in place as the labor market changes dramatically around them.

In short, labor market adaptation to the China trade shock appears generational. Incumbent manufacturing workers remained largely frozen in the declining manufacturing sector in their original locations, while a fresh set of workers—mostly younger, demographically distinct, and, in many cases, immigrants—entered employment in nonmanufacturing sectors of these local economies. At the level of local labor markets, this looks like a long-run adjustment, but it is easy to see how the dynamic of incumbent manufacturing workers slowly adjusting to living in rapidly changing places might give rise to divisive politics. We return to this point at the close of this essay.

U.S. manufacturing did not recover from the China trade shock

Manufacturing industries historically provided relatively high-paying job opportunities for workers without 4-year college degrees, whom we refer to as noncollege workers for brevity. Forty-three percent of noncollege manufacturing workers in 2000 were in the top one-third of all wage earners, as compared to only 23 percent of noncollege workers in nonmanufacturing jobs.9 Throughout the 2000s, manufacturing as a share of all jobs sharply declined: At the outset of 2000, manufacturing encompassed 13.2 percent of total U.S. employment. By the close of 2019, that share was 8.4 percent.10

To characterize the relationship between exposure to trade shocks and labor market adjustments, our analysis reports the estimated impact of a one-unit (one standard deviation) trade shock between 2000 and 2007 (the height of the China shock, prior to the Great Recession of 2007–2009) on the manufacturing employment in U.S. commuting zones over varying time horizons. This impact is expressed as a percentage of the total local working-age populations in these commuting zones in 2000.

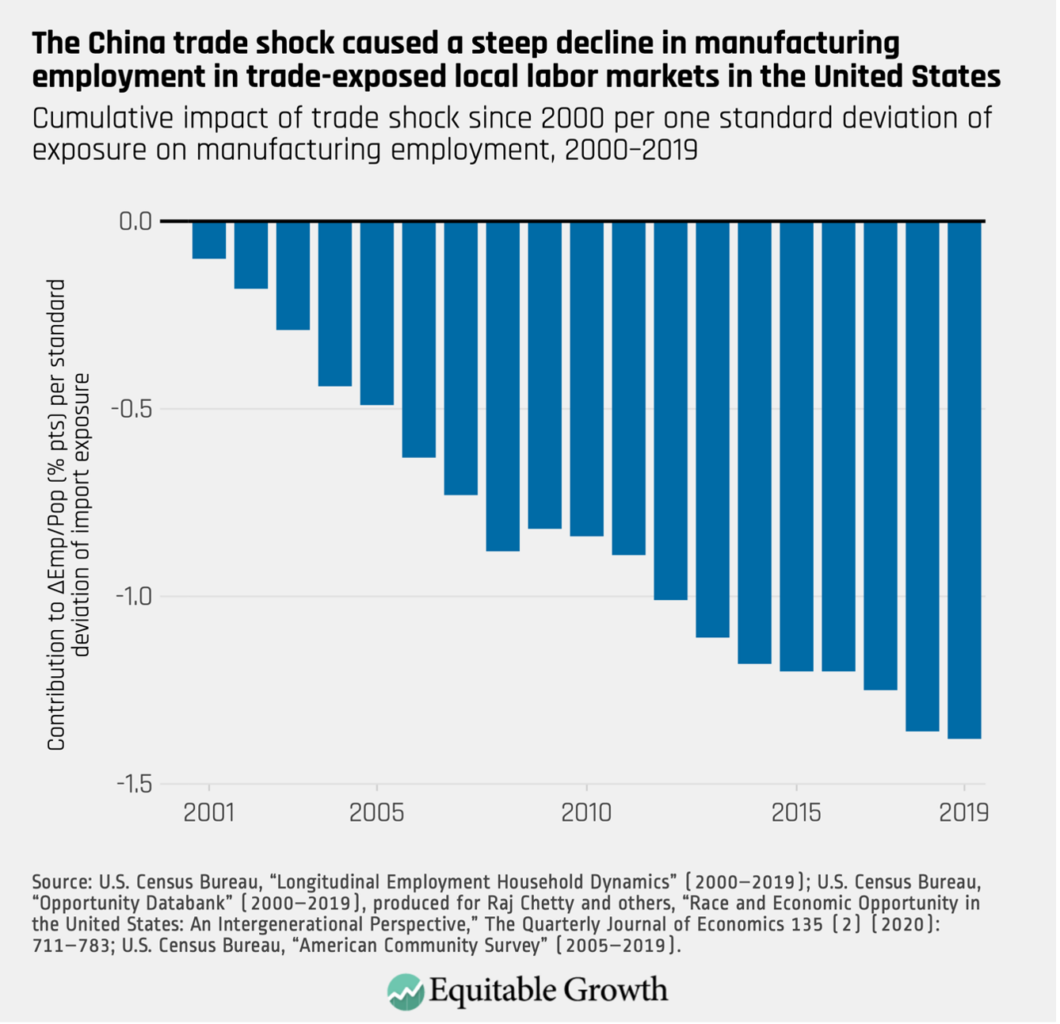

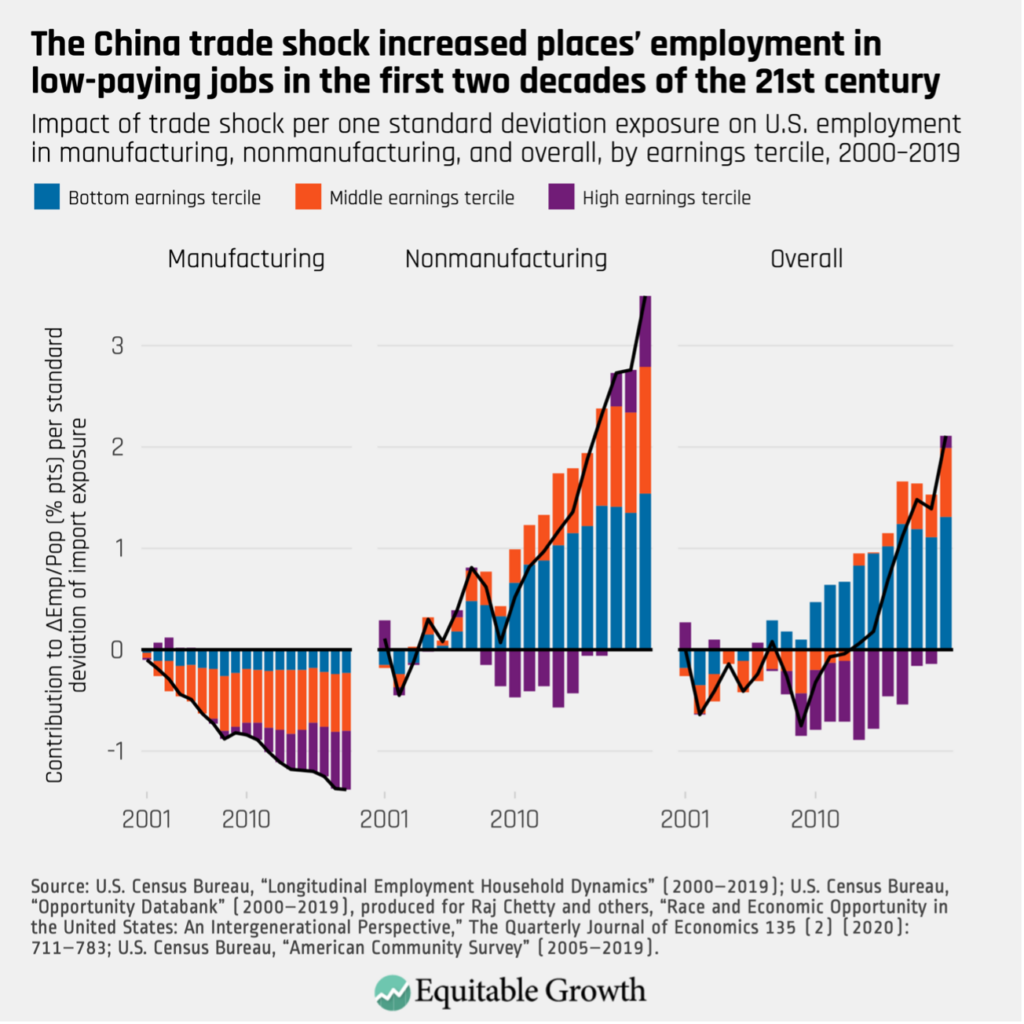

The role of the China trade shock in the decline in manufacturing employment is large, persistent, and cumulative. Between 2000 and 2019, manufacturing employment as a share of places’ initial working-age populations fell by an average of 1.4 percentage points per standard deviation of import exposure—amounting to the net displacement of 1 in 7 manufacturing workers. More than one-third of manufacturing workers (36 percent) were exposed to a shock of at least this size. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Economic theory suggests four main channels by which workers will adjust to adverse trade shocks. Workers will flow into and out of employment. They will flow across sectors, from manufacturing and nonmanufacturing jobs. They will flow to jobs in different labor markets that are presumably less exposed to trade shocks. And older workers will flow into retirement, replaced by young adults reaching working age. None of these four channels appear to have operated as robustly as economic theory expected in response to the China trade shock.

What’s more, the inflow of immigrant workers is the opposite of what economic theory predicts. In general, economists expect places experiencing economic duress to attract relatively few new job-seeking entrants. And in the case of U.S.-born White and Black workers, this is precisely what we find. But after 2010, trade-exposed local labor markets saw large influxes of U.S.-born Hispanic adults and foreign-born adults (primarily non-Hispanics).

Foreign-born workers, who tend to be much more geographically mobile than U.S.-born workers, tend to flow toward places with strong job growth in new, expanding industries, such as biotech, digital technology, and business and professional services. This is what occurred in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. The commuting zones whose manufacturing industries had been hollowed out by the China trade shock after 2000 by and large lacked a footprint in the most innovative sectors, making them unlikely job magnets. We suspect, however, that trade-exposed places offer a “brownfield” opportunity, in which rents were low, commercial properties were readily available, and where a growing retiree population—supported by earned Social Security retirement and Medicare benefits—had substantial need for care and hospitality services.

Our first finding is that as older manufacturing workers aged into retirement, new workers were not hired to replace them. That is, local labor markets exposed to the China trade shock did not register a subsequent manufacturing rebound. Instead, these labor markets experienced a continuous manufacturing decline through at least 2019, the end point of our sample.

A sharp decline in young workers entering manufacturing is the primary numerical contributor to the long-term decline in manufacturing employment, responsible for 56 percent of the contraction from 2000 through 2019. Among adult workers, the decline is due to reduced inflows into manufacturing employment of young, White and Black, non-college-educated men and women.

Economic theory also anticipates that workers exposed to adverse local labor market conditions would relocate to other labor markets to seek employment. For trade-exposed manufacturing workers in the first two decades of the 21st century, however, this is not what the data show. Rather than relocating to less trade-exposed labor markets, these workers became more likely to stay in their original locations. Some manufacturing workers did move, of course, to other labor markets in both exposed and nonexposed labor markets. But the geographic mobility of manufacturing workers in trade-exposed local labor markets fell, relative to comparable workers residing in nonexposed markets after the onset of the China trade shock.

Manufacturing workers’ geographic mobility in response to the trade shock also differed substantially by race and gender. In particular, the entirety of the increase in staying in trade-exposed labor markets was due to the reduced mobility of White male workers, who were and remain today the largest demographic group in the manufacturing sector.

What might explain this immobility? There are several plausible explanations. Place-based conceptions of personal identity are one explanation.11 Financial constraints or kinship ties that may deter workers from leaving are another.12 Tax-and-transfer payments, or income supports, provided to manufacturing workers, in combination with shock-induced lower costs of living may have incentivized workers to remain.13 The concurrent trade shock exposure of similar labor markets may also have reduced the attractiveness of moving.14

Unsurprisingly, workers from other locations also became increasingly less likely to migrate into manufacturing in trade-exposed labor markets. Thus, cross-market worker migration did reduce employment in trade-exposed locations. But it did so by deterring worker inflows by even more than it deterred outflows. The movement of manufacturing workers out of the labor force contributes modestly (by about one-third) to the numerical decline of manufacturing employment. Yet this impact dissipates by 2019 so that it is not much greater over the long run in trade-exposed versus nonexposed labor markets.

Earnings also were adversely impacted. Through 2019, earnings of trade-exposed manufacturing workers remained depressed relative to comparable workers in nonexposed locations. These outcomes, however, differed substantially according to workers’ initial earnings levels. Manufacturing workers initially in the bottom third of the U.S. wage distribution experienced a sharp reduction in employment. Workers initially in the middle third of the earnings distribution also experienced a reduction in employment, as well as an increase in their likelihood of falling into the bottom third of earnings. Workers initially in the highest third of earnings sustained a slight decline in employment, but by 2019, they essentially regained their ground relative to comparable workers in nonexposed locations.

Finally, while economic theory anticipates that trade-exposed manufacturing workers would transition to nonmanufacturing jobs, relatively few do so. This does not mean jobs aren’t reallocated within firms across sectors. Recent research documents that 40 percent of trade-induced job reallocation from manufacturing to nonmanufacturing stems from shifts within firms across locations.15

Our findings indicate, however, that manufacturing workers are not reallocated in tandem with these jobs. Though trade-exposed manufacturing firms may increase nonmanufacturing employment in less-exposed locations, these expansions do not, for the most part, directly re-employ workers displaced by the trade shock.16

This is ultimately not altogether surprising. Much of the job losses at these firms occurred in low-wage, less-educated areas in the South, where production work was concentrated. Much of the reallocation into nonmanufacturing by these same firms occurred in high-wage, high-education areas where design, management, and marketing were concentrated.

Local labor market adjustments are generational

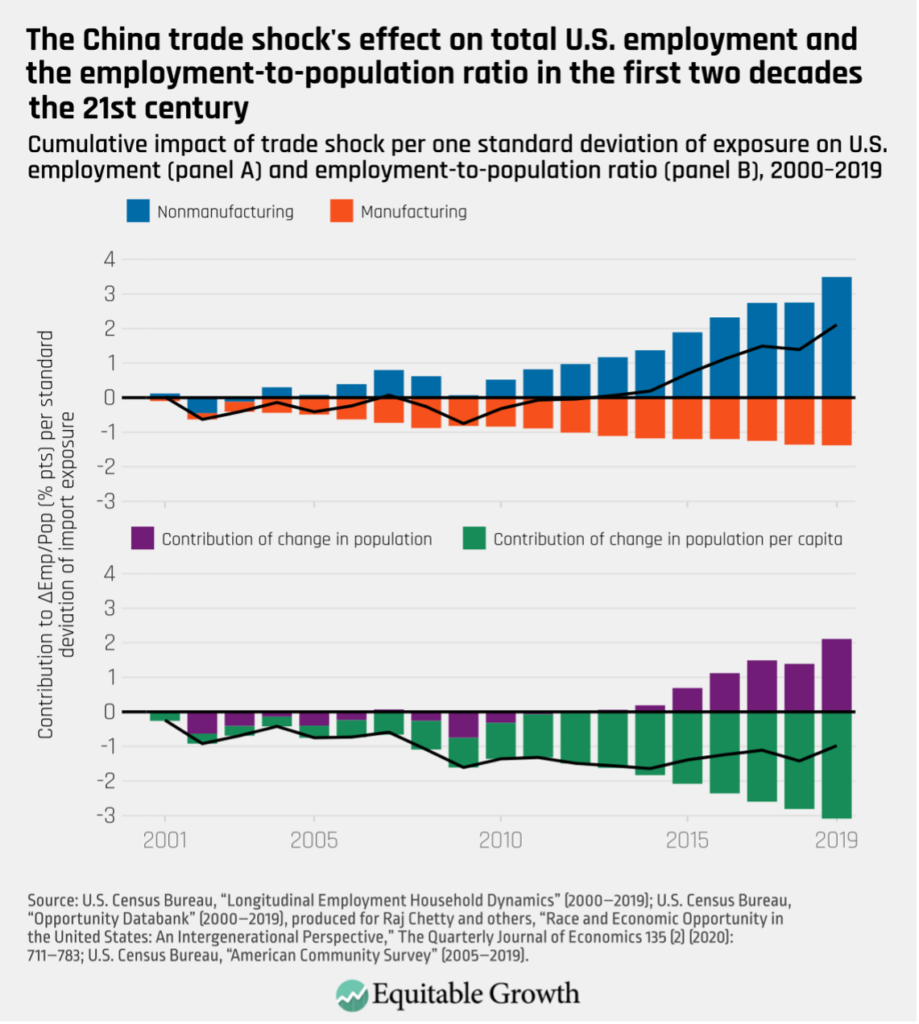

Although the employment and earnings prospects of workers who were initially employed in 2000 in trade-exposed labor markets declined, the labor markets in which they are located began to reconstitute in the first decade after the initial onset of the China trade shock. More specifically, increases in nonmanufacturing employment fully offset the numerical decline in manufacturing employment by 2013. From that year forward, employment grew more rapidly in trade-exposed labor markets, compared to nonexposed ones. Despite this rebound in the number of jobs, however, the employment-to-population ratio remained depressed in these locations as population growth outpaced employment growth. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The employment growth seen in Figure 2 after 2010 stems from two tributaries. Between 2001 and 2019, trade-shocked labor markets received steadily increasing inflows of workers who were already of working age (18 and over) in the year 2000 but not employed in the United States. As it turns out, these workers were largely immigrant adults who disproportionately found their first U.S. jobs in trade-exposed labor markets.

The second tributary of new workers—and the most significant driver of long-term growth in nonmanufacturing employment—was the entry in trade-exposed labor markets of young adults who reached working age approximately a decade after the initial shock in 2000. Many of these new entrants were U.S.-born Hispanics, but approximately one-quarter are immigrants.17

By contrast, the entry of U.S.-born White workers into trade-exposed labor markets fell sharply after the onset of the China trade shock, both in manufacturing and nonmanufacturing industries. The net increase in employment of young labor market entrants thus reflects a dramatic rise in inflows of U.S.-born Hispanics and immigrants, primarily non-Hispanic immigrants, offset in part by declining inflows of U.S.-born White workers. Also noteworthy is that women and college graduates were substantially overrepresented among these new entrants.18

Although the employment levels of U.S.-born White workers in trade-shocked areas remained largely unchanged between 2000 and 2019, their share of employment in these locations dropped while their average age rose (due to a decline in both the entry and exit of workers in this demographic group). Simultaneously, inflows of younger U.S.-born Hispanics and immigrant workers rapidly reshaped the demographic composition of local workforces.

Job quality in trade-shocked places declines

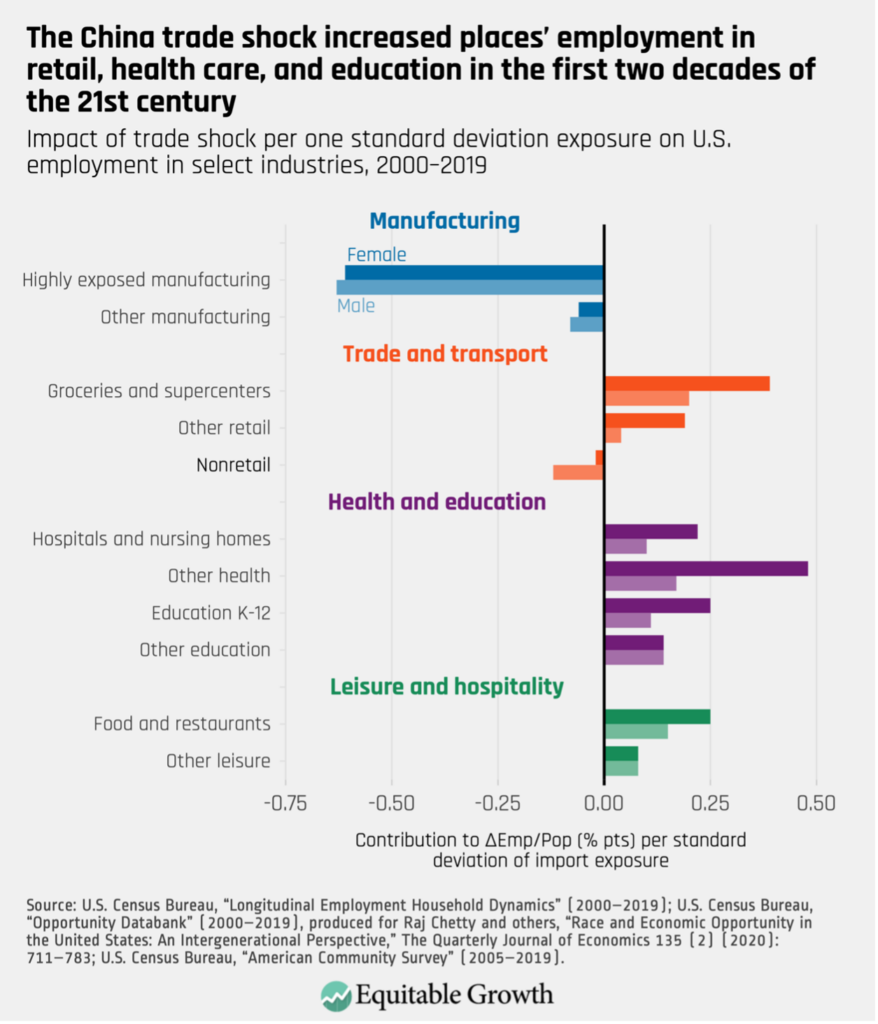

While manufacturing employment in trade-exposed local labor markets declined continuously after 2000, growing nonmanufacturing employment more than offset these losses from 2010 forward. The retail, health care, and education sectors experienced the largest employment growth, particularly in retail grocery, physician’s offices, Kindergarten-through-12th grade education, and restaurants. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Figure 3 also highlights that as trade shocks remade the industrial composition of trade-exposed labor markets, the gender composition of employment shifted markedly. Despite the overrepresentation of men in manufacturing, trade-induced losses in manufacturing were equally sizable among men and women.19 But the growth in nonmanufacturing employment had a distinct gender skew: Women’s employment in nonmanufacturing rose by 1.54 percentage points per standard deviation of shock exposure between 2000 and 2019, while men’s employment rose by just 0.57 percentage points. Thus, more than three-quarters of net employment growth in trade-exposed labor markets reflected an increased employment of women.

In the three largest growth subsectors—retail, health, and food and restaurants—women’s employment increased by more than twice that of men. One proximate explanation for this pattern is that the sectors leading the employment recovery were all disproportionately female, though of course men entered these sectors as well. The rise in female employment was disproportionately driven by the entry of adult female immigrants. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Since post-shock employment increases were disproportionately concentrated in traditionally low-paid service-sector industries, it is no surprise that the wage structure in trade-exposed labor markets shifted toward lower pay. As shown in Figure 4, almost all trade-induced job losses in manufacturing are accounted for by a loss of middle and upper-third jobs. Conversely, almost all employment gains in nonmanufacturing are accounted for by bottom-third and (secondarily) middle-third jobs. As such, approximately two-thirds of overall employment growth in trade-exposed labor markets between 2000 and 2019 is accounted for by rising employment in the bottom third of the earnings distribution.

In summary, the post-shock labor force in trade-exposed local labor markets as of 2019 consisted of two distinct groups: a new generation of workers who found employment in low-paid jobs concentrated in the service sector and a cohort of long-term incumbent manufacturing workers whose employment and earnings did not rebound from the manufacturing trade shock that began at least a decade earlier. Despite the eventual rebound in overall employment, the employment-to-population ratio remained depressed, low-pay jobs replaced high-pay jobs, and there remained groups of long-term economic losers in trade-exposed places.

Trade shocks, tariffs, and the U.S. political landscape

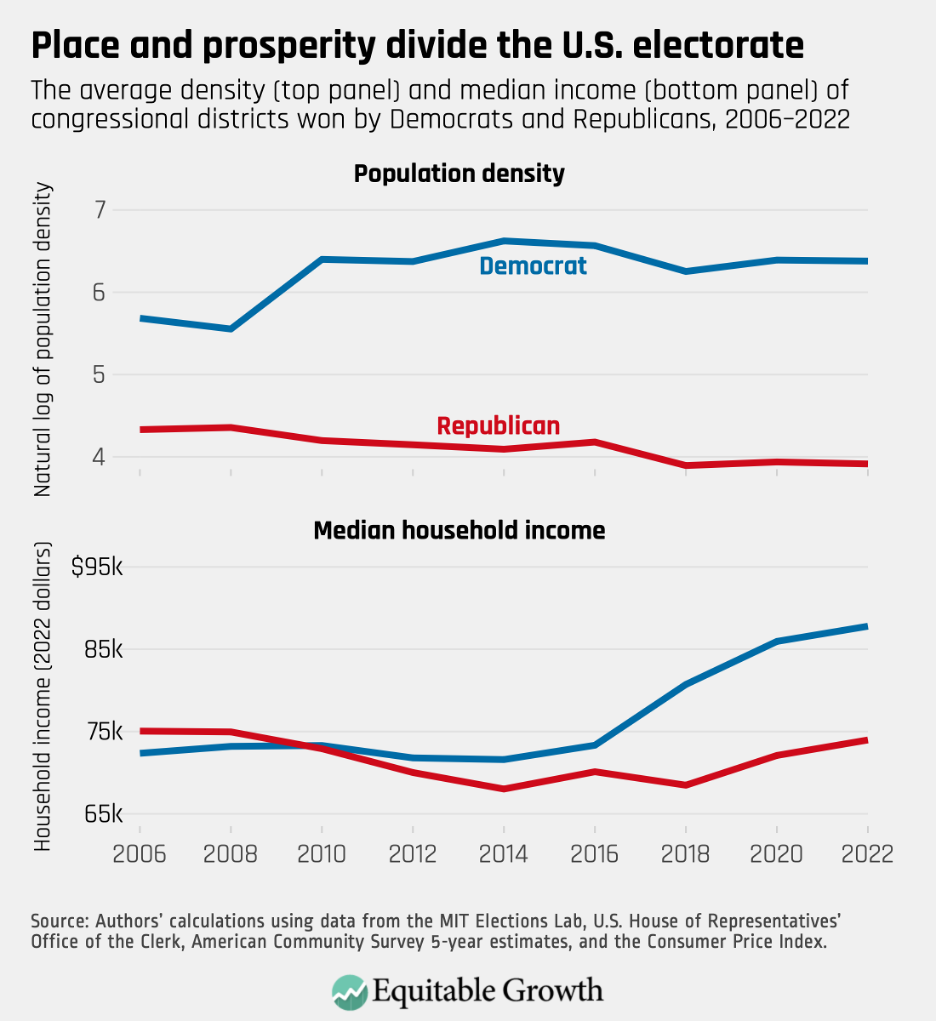

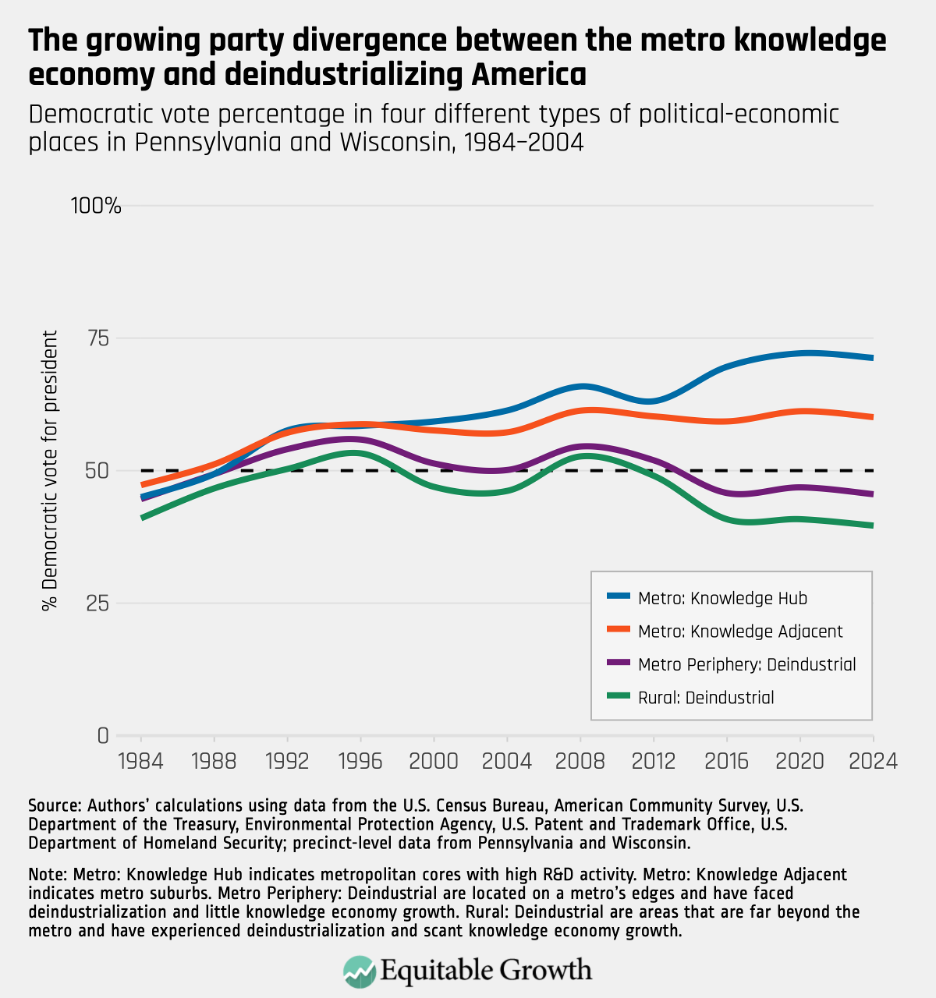

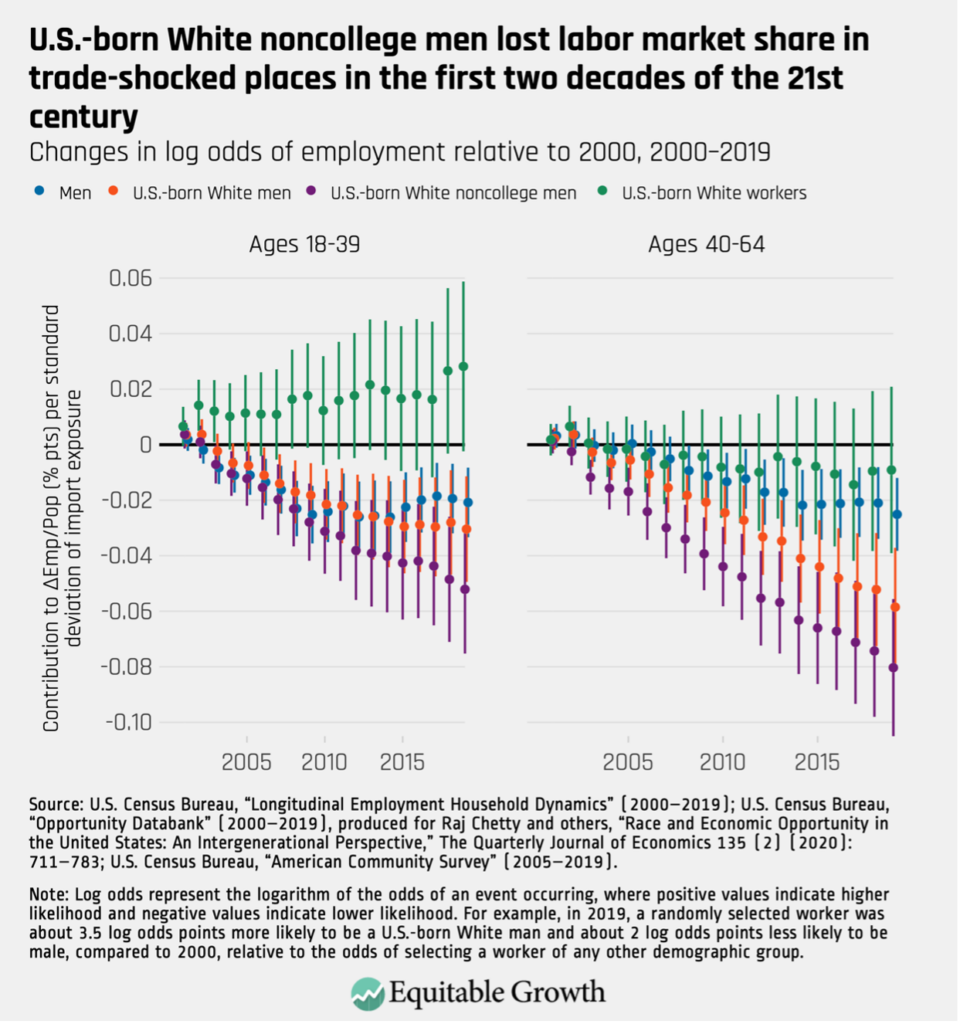

By reshaping employment and opportunity, perceptions of the China trade shock may also recast political preferences, including support for right-wing populist candidates and parties. As seen above, White non-college-educated males, a core constituency of President Donald J. Trump, experienced particularly adverse employment outcomes post-shock. For incumbent manufacturing workers in trade-shocked areas, declining economic prospects were closely followed by the arrival of immigrants and broader demographic shifts. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

The relative decline in the prevalence of U.S.-born, White, noncollege male workers in trade-exposed labor markets is shown vividly in Figure 5. While the share of U.S.-born White workers in trade-exposed labor markets remained relatively stable in the two decades following the China trade shock, the prevalence of noncollege U.S.-born White men fell steeply—by 8 percentage points for workers ages 40 to 64 and by 5 percentage points for workers ages 18 to 39. White noncollege men thus increasingly found themselves working in more diverse labor markets alongside colleagues of different racial, ethnic, and national backgrounds.

Against this backdrop, it is natural that the Fox News Network, with its appeal to conservative voters, generally aligned against freer immigration and in favor of strengthening U.S. manufacturing and gained media share in trade-exposed markets as ideological affiliations and voting patterns of White voters shift to the right.20 The China trade shock’s polarizing ideological impact is directly manifest in the increased electoral success of Republicans at the expense of moderate Democrats in trade-exposed voting districts over the first two decades of the 21st century.

Investigations into the political effects of surges of Chinese import competition in Europe yield corresponding patterns. In Germany, France, Italy, and other Western European nations, local exposure to Chinese import competition induced electoral shifts to the right.21 These studies highlight the relevance of economic experiences, such as trade shocks, in shaping political outcomes.

Under the first Trump administration’s trade war in 2018–2019, its promised manufacturing employment growth from tariffs failed to materialize while consumer prices rose.22 Even though 37 percent of Republican voters agreed with the proposition that the United States is hurt more than China by tariffs, 80 percent remained in favor of tariffs in a 2019 poll.23 Voters in communities protected by new U.S. import tariffs also became less likely to identify as Democrats and were more likely to support President Trump in the 2020 presidential election.24

In response to the increasing political resonance of trade, Republicans became more likely to interact with trade issues via China-critical communications strategies.25 Trade and trade policies have remained salient political issues through the start of the second Trump administration. Surging imports of critical value-added goods from China—such as electric vehicles, solar panels, and semiconductor chips—present a not insignificant risk of a second China trade shock. The political and economic consequences will depend not only on the actions of foreign exporters, but also on how the United States responds.

Conclusion

The persistent earnings losses and employment displacement triggered by the China trade shock did not just alter local labor markets—they also reshaped political behavior, as declining job prospects, demographic shifts, and foregone mobility fueled a concentrated and understandably bitter electoral response. While net employment in trade-exposed places eventually rebounded by 2019, incumbent manufacturing workers’ economic prospects did not. Trade-shocked places adapted through generational adjustments made possible by immigrants and young workers entering the labor force.

An at-first-blush appealing response to these findings, and the continuing impact of the China trade shock over the past 4 years, is that governments should invest in place-based policies that assist displaced workers to adapt by investing in their communities. As our results imply, however, place-based trade-adjustment policies carry complex targeting effects—offering stability for incumbent workers who are less likely to relocate while simultaneously shaping opportunities for new local labor market entrants.

To the extent that workers’ experiences of the economic adjustment process contribute to political polarization, place-based policies that mitigate local trade-shock-induced distress may plausibly temper its scope and trajectory.26 Even as the economic consequences of the China trade shock constrained the geographic mobility of incumbent workers—narrowing the physical and economic boundaries of their lives—the political reverberations of this same shock extend nationally, as concentrated disaffection becomes increasingly consequential in a polarized and closely contested electoral landscape.

About the authors

David Autor is the Daniel and Gail Rubenfeld Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is co-director of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Labor Studies Program and co-leader of both the MIT Work of the Future Task Force and the MIT J-PAL Work of the Future experimental initiative.

David Dorn is a professor of globalization and labor markets at the University of Zurich and affiliated professor at the UBS Center of Economics in Society. He was previously a tenured associate professor at the Center for Monetary and Financial Studies in Madrid, a visiting professor at Harvard University, and a visiting scholar at Boston University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Chicago.

Gordon H. Hanson is the Peter Wertheim Professor of Urban Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. He is a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and co-editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives. *

*The authors note that the U.S. Census Bureau has ensured appropriate access and use of confidential data and has reviewed these results for disclosure avoidance protection (Project 7511151: CBDRB-FY24-CES014-008, CBDRB-FY24-0253, CBDRB-FY24-0328, CBDRB- FY24-0391, CBDRB-FY24-0433, CBDRB-FY25-0060). They also note that the main findings presented in this essay were originally reported in “Places versus People: The Ins and Outs of Labor Market Adjustment to Globalization” by David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, Maggie R. Jones, and Bradley Setzler (2025).27

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!