Elisabeth Jacobs, Senior Director for Policy and Academic Programs, Washington Center for Equitable Growth, testifying before the United States Joint Economic Committee on “What Lower Labor Force Participation Rates Tell Us about Work Opportunities and Incentives”

I would like to thank Chairman Coats, Ranking Member Maloney, and the rest of the Committee for inviting me here today to testify.

My name is Elisabeth Jacobs and I am Senior Director for Policy and Academic Programs at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. The center is a research and grant-making organization dedicated to understanding what grows our economy, with an emphasis on understanding whether and how economic inequality impacts economic growth and stability.

I am pleased to be here today to address an important topic for understanding the health of the labor market and the economy overall: the labor force participation rate, which currently stands at 62.6 percent. The continued decline of the unemployment rate since 2010 is the most commonly cited piece of evidence that the labor market is recovering. Indeed, it is undeniable that the labor market has improved considerably in the years since the Great Recession, as unemployment has fallen to 5.3 percent, its lowest rate in seven years. Despite this progress, however, the labor market remains troubled. Simply relying on the unemployment rate as an indicator of the health of the job market masks underlying problems, many of which have persisted for decades. In order to fully understand the current state of the labor market, policymakers need to take into account not just the unemployment rate, but also other indicators of how the labor market is functioning, including the labor force participation rate.

My testimony draws five major conclusions:

- The labor market is recovering from the deepest economic downturn since the Great Depression. The private sector has added 12.8 million private-sector jobs over 64 straight months of job growth, the longest streak of private-sector job creation on record. The unemployment rate is down to 5.3 percent, a seven-year low.

- While the labor market is on the mend, looking solely at the falling unemployment rate overstates that recovery. Other indicators of labor market health, including the labor force participation rate, suggest that there is more work to be done.

- The decline in the labor force participation rate predates the Great Recession and is mainly the result of several structural changes in the labor market, including the aging of the workforce.

- Recent declines in the labor force participation rate that are not explained by long-standing structural changes are largely due to persistent business cycle effects. Five years into the labor market’s recovery from the most severe recession in recent history, demand remains slack.

- Policy can play an important role in boosting the labor force participation rate, but policymakers need to focus on the correct levers. Persistent slack demand suggests that fiscal and monetary policies are an important first step. In the absence of political action on those fronts, however, family-friendly policies and criminal justice reform are important options.

The rest of my testimony will 1) discuss recent trends in the unemployment rate and other measures of the health of the labor market, 2) examine the potential reasons for the long-run decline in the labor force participation rate, and 3) review the research on the trends in the labor force participation rate since the Great Recession. I conclude by suggesting key implications for policy moving forward.

Download the full pdf for a complete list of sources

Trends in the unemployment rate and the health of the labor market

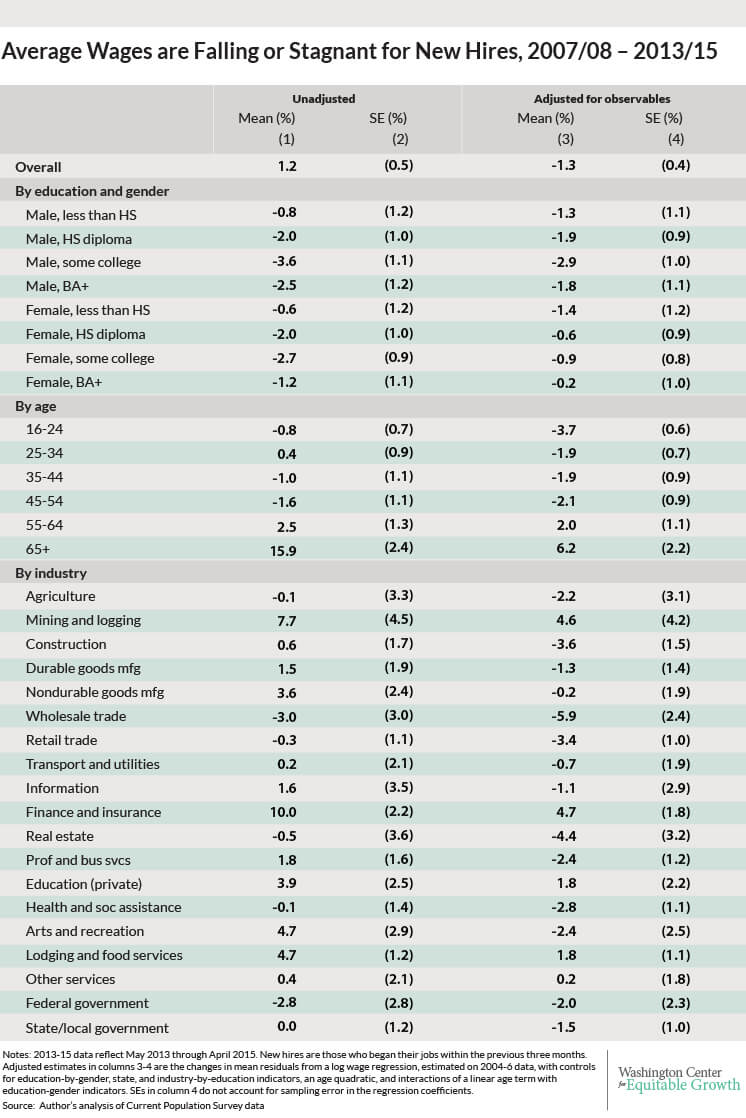

The Great Recession’s impact on the labor market was devastating. In December 2007, the month the recession began according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the unemployment rate was 5 percent. By the end of the recession, in June 2009, the unemployment rate hit 9.5 percent and continued to climb until it peaked at 10 percent in October 2009. Over the past five and a half years, the labor market has made substantial progress back toward where it was before the financial crisis. The economy is in the midst of the longest streak of private-sector job growth on record, with 12.8 million jobs created over 64 straight months. The most notable headline has been the continued downward trajectory in the unemployment rate. Joblessness as defined by the official unemployment rate has been on the decline more than 5 years, and stood at 5.3 percent in June, according to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Indeed, an observer looking solely at the unemployment rate might conclude that the labor market is roughly as healthy as it was prior to the Great Recession. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

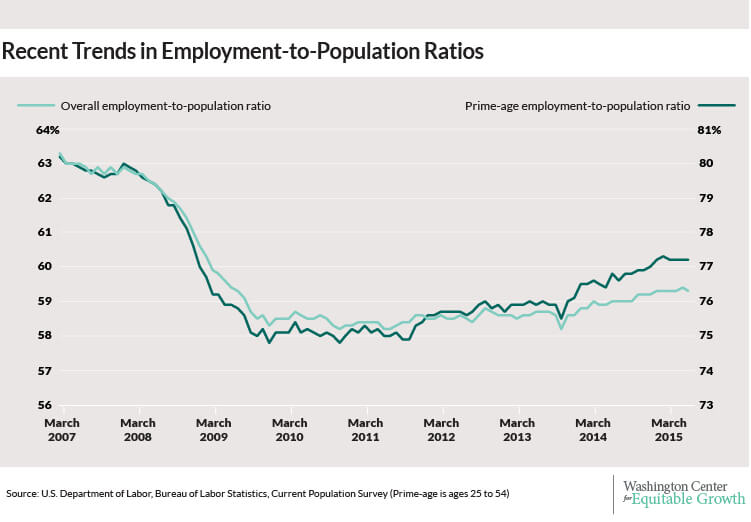

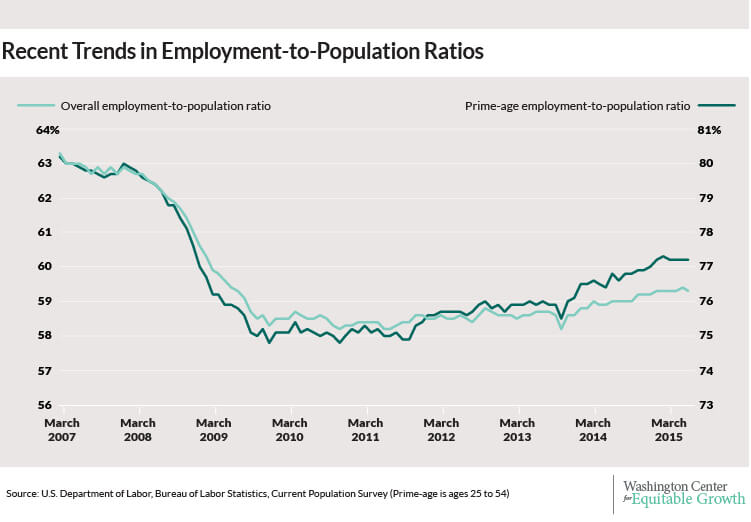

Yet, other measures of the labor market tell a more complicated story. Consider the employment-to-population ratio, which is the share of the total population currently employed. Whereas a decreasing unemployment rate is a sign of improvement in the labor market, an increasing employment ratio can be an even stronger signal of improvement. Unfortunately, the trend in the employment ratio is less sanguine than trend in the unemployment rate.

The employment ratio plummeted during the Great Recession, unsurprisingly. In December 2007, the employment ratio was 62.7 percent, and it fell to a nadir of 58.2 percent in November 2010. The share of the population currently employed has improved over the course of the recovery, and has been growing for just under four years, reaching 59.3 percent in June. Yet it remains 3.4 percentage points below its level prior to the Great Recession, suggesting continued weakness in the labor market. A second key point to keep in mind is that, like many indicators of underlying labor market health, the downward trajectory of the employment ratio pre-dates the Great Recession. The employment ratio peaked in December 2006, a year before the financial crisis, and was higher still in April 2000, when it hit 64.7 percent.

The prime-age employment ratio, or the share of the total population between the ages of 25 and 54 years old with a job, has followed a similar trajectory. Its pre-recession peak, in December 2007, was 79.7 percent. But the prime-age employment ratio was just 77.2 percent in June, a current gap of 2.5 percentage points. The labor market has made considerable gains in the light of the worst recession since the Great Depression. But looking at these employment-to-population ratios is one indication that reveals how those gains are incomplete. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Why does the unemployment rate indicate a more complete labor market recovery than does the employment rate? The answer has to do with the intertwined and complicated relationship between the unemployment rate and the labor force participation rate.

The unemployment rate is calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics using the Current Population Survey, or CPS, a survey that interviews a sample of households every month and details information about individuals over the age of 16. Individuals who had a job during the week they were interviewed are counted as employed. But not all workers who lack a job are counted as unemployed. According to the CPS, a worker is only officially unemployed if she lacks a job, has actively searched for a job in the last four weeks, and is available to work. Employed workers and officially unemployed workers are together the “labor force.” Any worker without a job who is not counted as officially unemployed is considered to be “not in the labor force.” The official unemployment rate is then calculated by dividing the number of officially unemployed by the labor force. It is an important measure of labor market health because of the clarity of what’s being counted: the unemployment rate is a clear indication of the share of Americans who are actively looking for work. The labor force participation rate is the labor force divided by the total population.

When we think about the unemployment rate declining, we usually think of a situation where an unemployed worker gets a job, moving from unemployment to employment. The ranks of the unemployed would decline, while the size of the labor force would stay the same. The result would be a lower unemployment rate. But the unemployment rate could decline in another way. An unemployed worker could drop out of the labor force, reducing the size of both the number of officially unemployed workers and the labor force. This also would also lead to a decline in the unemployment rate.

An example can help clarify this point. Imagine a labor market with 150 potential workers: 95 are employed, 5 are officially unemployed and 50 are not in the labor force. The official unemployment rate would be 5 percent (5 unemployed workers divided by a labor force of 100 workers.) If one of the unemployed workers got a job, then the unemployment rate would decline to 4 percent (4 unemployed workers divided by a labor force of 100 workers). But if instead an unemployed worker retired and left the labor force, then the unemployment rate would decline to 4.04 percent (4 unemployed workers divided by a labor force of 99 workers). In the first case, the labor force participation rate would stay the same at 66.7 percent (100 divided by 150), but in the second case it would drop to 66 percent (99 divided by 150).

So trends in the unemployment rate are intimately tried to trends in the labor force participation rate. While the decline in the labor force participation rate was particularly stark during the Great Recession, the trend predates it. It’s to the long-term term that I now turn.

The long-run decline in the labor force participation rate

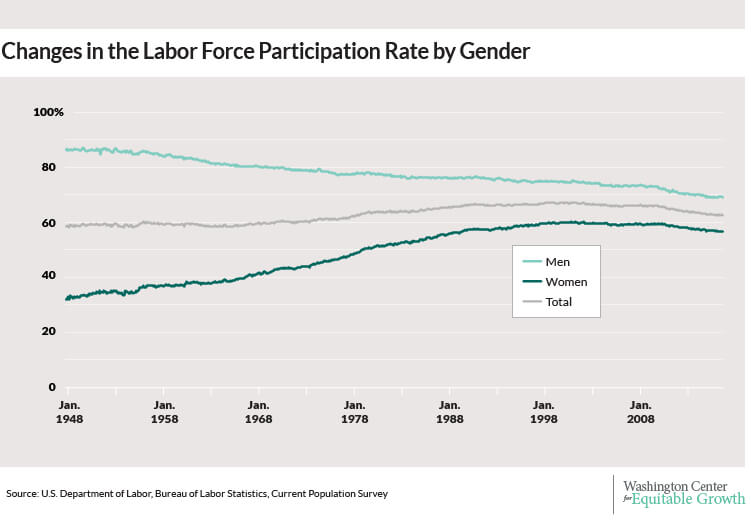

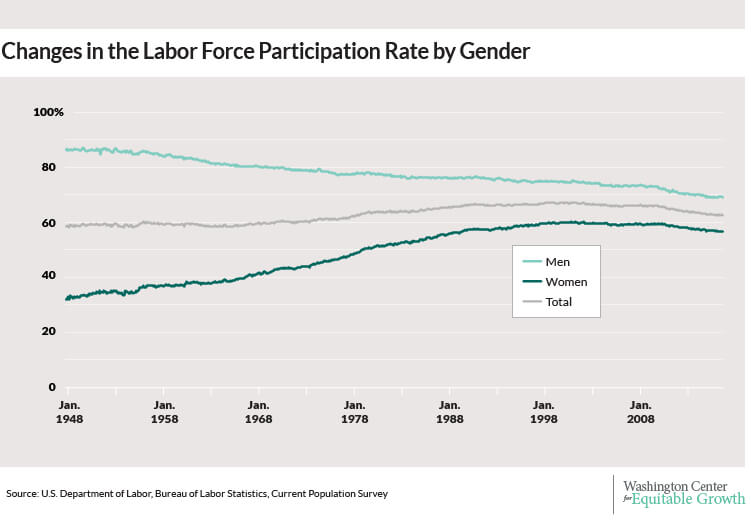

The Bureau of Labor Statistics has been keeping track of the labor force participation rate since January 1948, when the rate was just 58.6 percent. Labor force participation stayed at about this level until 1965 when it began a climb that would last 35 years, until it peaked in April 2000 at 67.3 percent. What caused the steady increase in the rate? Looking at the difference in labor force participation by gender reveals the answer. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The labor force participation rate for men has been on a downward trajectory for nearly 60 years, almost from the moment the agency started keeping track of the statistic. In January 1948, male labor force participation was 86.7 percent. By April 2000, when overall labor force participation peaked, male labor force participation had fallen to 74.9 percent. For women, the trend has operated in precisely the opposite direction. In April 1948, the participation rate for women was 32 percent. Female labor force participation steadily increased for the next half century, peaking at 60.3 percent in April 2000. Over the second half of the 20th century, women moved into the labor force—and were increasingly likely to stay there, even after becoming mothers. This sea change in women’s labor force participation is what helped buoy the overall labor force participation rate, even as men were increasingly less likely to be in the labor force.

Since 2000, however, the growth in women’s labor force participation has stalled out. Men’s labor force participation has continued to decline. So the question remains: what is responsible for the decline beginning in 2000?

The clearest cause of the decline in the overall labor force participation rate is the aging of the population. The Baby Boom generation, born between 1946 and 1964, is a large cohort of workers whose retirement age coincides with decline in labor force participation that began in 2000. As these workers retired, they left the labor force and in turn pushed down the total labor force participation rate.

At the same time, the participation rate for younger workers (age 16 to 24 years) has been on the decline for decades as well. The downward trend in labor force participation for younger Americans is explained by increased schooling: younger workers are more likely to stay in school longer, as college attendance has become substantially more common. So, a positive development—increased educational attainment—pushed down the labor force participation rate.

Yet the demographic shifts described above cannot explain the entire decline in the labor force participation rate. Prime-age workers’ labor force participation has also been on the decline. The rate of participation for workers ages 25 to 54 declined from 84.4 percent in April 2000 to 83.1 percent in December 2007, on the eve of the Great Recession.

Women’s labor force participation was driving the overall upward trend in labor force participation through 2000, so the plateau and then decline in women’s participation in the ensuring years is an important factor for explaining the national trend. Understanding why women’s labor force participation has stalled is key to reversing the downward trends in the national rate. In 1990, the United States had the sixth-highest female labor force participation rate amongst 22 high-income OECD countries. By 2010, its rank had fallen to 17th. Why have other high-income countries continued their climb while the United States has stalled? Research by economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn suggests that the absence of family-friendly policies such as paid parental leave in the United States is responsible for nearly a third of the U.S. decline relative to other OECD economies. As other developed countries have enacted and expanded family-friendly policies, the United States remains the lone developed nation with no paid parental leave.

Trends in labor force participation since the Great Recession

While labor force participation was declining before the Great Recession, the downward trend accelerated during the economic crisis. The raw data cannot tell us how much of the decline since the end of 2007 is a continuation of the longer-term trends discussed above, and how much of the decline is due to the lingering effects of the Great Recession. Untangling these two trends—the structural and the cyclical—has become an important and highly contested debate amongst economists and other labor market analysts.

Some research on the recent decline argues that a large portion was due to the structural forces in place before the recession, and concludes that not much of the current lower rate is due to weakness in the labor market due to the Great Recession. A 2014 study by economist Stephanie Aaronson and her colleagues finds that the majority of the decline is due to structural forces. According to their calculations, cyclical weakness is responsible for pushing down the labor force participation rate between 0.24 and 1 percentage point in the second quarter of 2014. In June 2014, the participation rate was about 3 percentage points below its pre-recession level, meaning the recession was only responsible for, at most, one-third of the lower rate.

Other research finds a much larger role for the recession, albeit over a different time frame. A 2012 study by economist Heidi Shierholz finds that only one-third of the decline between 2007 and 2011 was due to structural factors and the other two-thirds of the decline was due to the cyclical impact of the Great Recession.

An analysis from White House Council of Economic Advisers finds a result somewhere in the middle of these two estimates. The CEA, using conservative estimation techniques, concludes that about half of the decline from 2007 to the middle of 2014 is due to the aging of the population, one-sixth is part of a cyclical decline consistent with what we would expect given previous recessions, and the final third is a combination of other structural trends from before the recession and “consequences of the unique severity of the Great Recession.”

So, while there is room for the rate to move upward as the economy strengthens, long-term forces will continue to exert downward pressure on labor force participation. So far in 2015, the labor force participation rate has been holding fairly steady, moving sideways instead of downward. While the June report saw a 0.3 percentage point decline in the participation rate, we should be cautious about drawing conclusions from this dip. The monthly CPS data are noisy, meaning that several months’ of consistent movement are necessary before concluding that a trend is in place. Drawing conclusions from last month’s numbers is particularly risky, due to an anomaly in the timing of survey data collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for the June report.

Policy implications moving forward

What are the implications for future policy? If policy makers want to raise the labor force participation rate, or at least keep it as high as possible, a variety of options belong on the table.

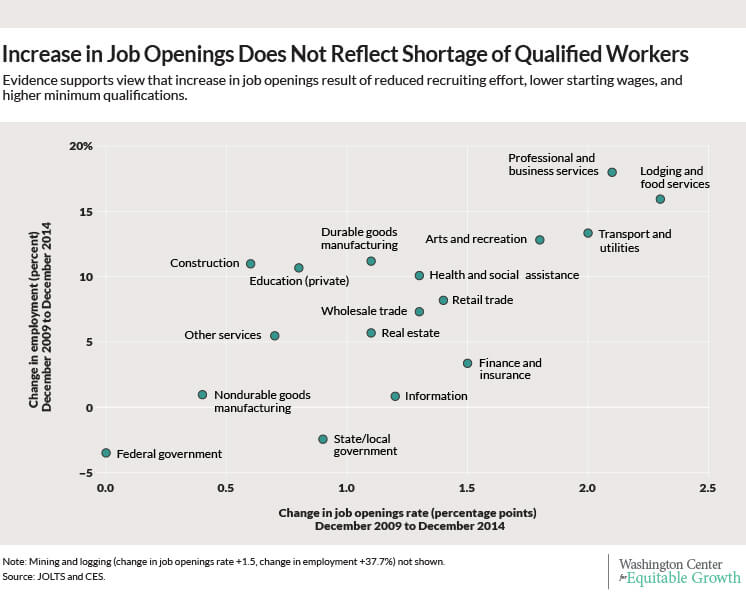

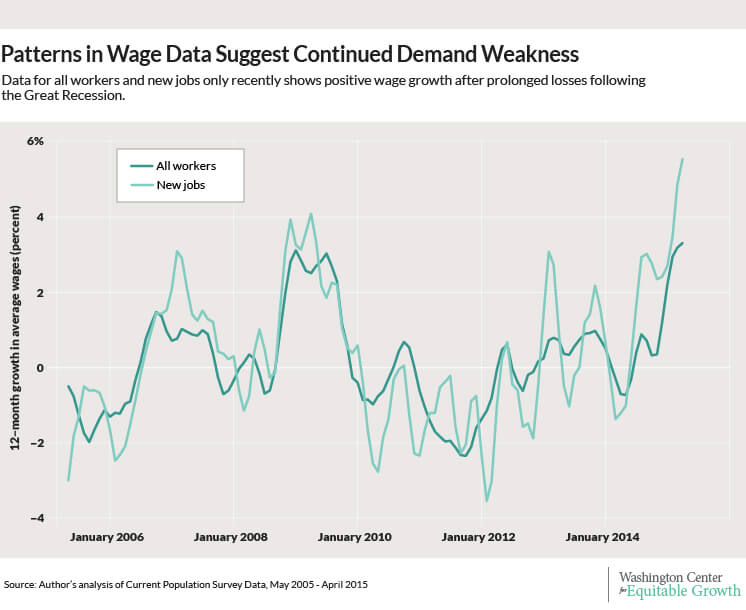

Fiscal and monetary policy that focuses on strengthening economic growth and prioritizing full employment can help boost the labor force participation rate. A new study from economist Jesse Rothstein finds lackluster employment growth across nearly all industries between 2009 and 2014, reflecting a continued shortage of demand for all workers. Stronger economic growth can help pull more workers into the labor force if they see higher wages being offered by employers. Doing so requires more stimulus through fiscal policy, such as increased infrastructure investment. According to the International Monetary Fund, boosting infrastructure spending can accelerate economic growth by 1.5 percent in the short-term. This increased growth would help create jobs and pull discouraged workers back into the labor force, as well as improving the health of the economy in the longer-term. More accommodative monetary policy also has immense potential to stimulate labor demand. Fiscal and monetary policies are immensely important, but smart microeconomic policies could help as well.

First, the absence of family-friendly policies in the United States is a key reason for the decline in the overall labor force participation rate and the stalling out of women’s labor force participation. The Mad Men Era is over, to the great relief of many women. But public policy has not kept up with the needs of working families, and balancing the competing demands of work and home remains a fundamental challenge for millions of households. Recent research suggests that the failure to adapt our policies to meet the demands of the modern American family means that women’s labor force participation has stagnated. Paid family leave, flexible scheduling, affordable high-quality childcare, and universal pre-kindergarten are all policies that could play a major role in jump-starting the engine of women’s labor force participation. By providing policies that recognize individuals’ dual roles as both workers and caregivers, we have the opportunity to attract and retain talent in the labor force.

The potential impact of paid family leave on the labor force participation rate is worth discussing in a bit more detail because of the demographic trends discussed earlier. Research suggests that paid parental leave can substantially improve mothers’ labor force participation, because it encourages them to return to their job following a period of bonding with a new baby. But caregiving extends beyond children, as anyone who has provided care for an aging relative well knows. The share of prime-age workers with eldercare responsibilities is increasing as the Baby Boom cohort ages. Unpaid family caregiving is the most common form of eldercare for people of advanced age. Nearly half of all individuals who provide eldercare are part of the “Sandwich Generation,” simultaneously responsible for both aging parents and young children. Paid family leave that allows workers to take temporary time off to care for a loved one—whether that loved one is a new child or an aging parent—is a potentially powerful tool for bolstering labor force participation.

A second proactive policy option to improve labor force participation is a criminal justice reform agenda that includes a reduction in the incarceration rate and policies to reduce discriminatory employment practices against those with criminal records. The U.S. incarceration rate is currently the highest in the world, a consequence of three decades of dramatic growth in the prison population. While the crime rate has fallen over the same period that the prison population has grown exponentially, research shows that the efficacy of increased incarceration as a crime control technique is virtually non-existent; crime rates rise and fall independent of incarceration rates since the 1990s. Coupled with the rise in incarceration, nearly one in three adults in 2010 had a serious misdemeanor or felony arrest that can show up on a routine background check for employment, and a substantial share of discouraged workers report a felony conviction. Nine in ten large corporations report that they conduct criminal background checks, and a wide range of research suggests that a criminal record (both felony and misdemeanor charges, regardless of age) plays a significant negative role in an individual’s employment prospects. New research by economist Michael Mueller-Smith shows that overly aggressive criminal justice policies can significantly reduce the labor force participation of individuals once they leave prison or jail.

Taken together, the impact of our nation’s current criminal justice policies suggest that reform could play a significant role in improving labor force participation. In the long run, reducing flows into the prison population could help boost the labor force participation rate. In the short-term, “ban the box” policies that remove the criminal history question from job applications and postpone the criminal background check until later in the hiring process could help pull some discouraged workers back into the labor force.

It is important to avoid being distracted by policies that have little to do with the trends in the labor force participation rate. Social Security Disability Insurance, or SSDI, for example, has been cited as a program that reduces the participation rate by discouraging work. Proponents of this hypothesis argue that more relaxed medical screening for disability and an increase in the program’s income-replacement rate have increased the disability rolls and pulled able-bodied workers out of the labor market. But studies suggest that the increase in the number of Americans receiving SSDI may be a simple matter of demographics. For instance, economist Monique Morrisey uses the demographic-adjusted disability incidence rate, which shows that after controlling for the aging of the population the rate for men has been on the decline for the last 20 years. At the same time, the age-adjusted rate for women has increased, but to a level similar to the age-adjusted rate for men. This analysis indicates that disability has not become more prevalent, but rather that the aging of the workforce has been the primary cause of the increase in SSDI receipt. Of course, policymakers may have other reasons for wanting to reform the disability insurance program, but we should not expect changes in SSDI to provide a major boost to the labor force participation rate.

Similarly, the Affordable Care Act has been cited as a program that could reduce the labor force participation rate and depress overall labor supply. To a certain extent, this is true. The Congressional Budget Office’s model predicts that workers will supply less labor once the five-year-old health care law is fully implemented in 2016. Note, however, that this reduction in labor supply is due to choices by the workers, not because of a reduction in employers’ demand for labor. Some of this decline in labor supply will come as a reduction in the hours worked by some workers, rather than a decline in the number of workers employed. In other words, the program may lead to an increase in voluntary part-time work. Data from the past several years shows just that trend: an increase in workers voluntarily working part-time. While the ACA may have impacts on labor supply, those effects generally reflect a positive outcome for workers.

Conclusion

Untangling the causes of causes of labor market trends is a tricky endeavor, particularly given the intersection of a long-run trend with the cataclysmic recession of 2007-2009. The drop in the labor market participation rate means that the unemployment rate overstates the extent of the labor market recovery. While the decline in labor force participation was underway decades before the Great Recession began, the downturn played a significant role in the accelerating the recent decline. Demographic forces, namely the aging of the population, are putting significant downward pressure on the labor force participation rate. While the primacy of demographics means limits the extent to which policies can impact increase labor force participation, this structural challenge does not mean that policy has no role to play. The trick for policymakers is to be strategic, and to pull the levers with the most potential to jump-start the labor market back into high gear.