Income inequality has been rising for decades in the United States. While there are many reasons why this trend may be concerning, one particular worry for economists and policymakers is the effect that it might have on macroeconomic activity through what is sometimes called the aggregate demand channel. The argument is as follows: There is some evidence that the rich save more than the poor. A rise in income inequality implies more income accruing to the rich, a trend that may be depressing overall consumption and in turn lowering aggregate output and employment.

A competing argument, however, focuses on the resulting increase in savings, which could be expected to translate into an increase in investment, raising the capital stock and economic output in the future. In this view, higher income inequality creates some losers, but it leads to an increase in aggregate Gross Domestic Product. Whether the first or the second effect dominates depends on what macroeconomists call general equilibrium considerations, and in particular, on our presumptions about the response of monetary policy to rising income inequality. This column examines those two effects, based on our newly released working paper.

A model of the effect of income inequality on aggregate demand

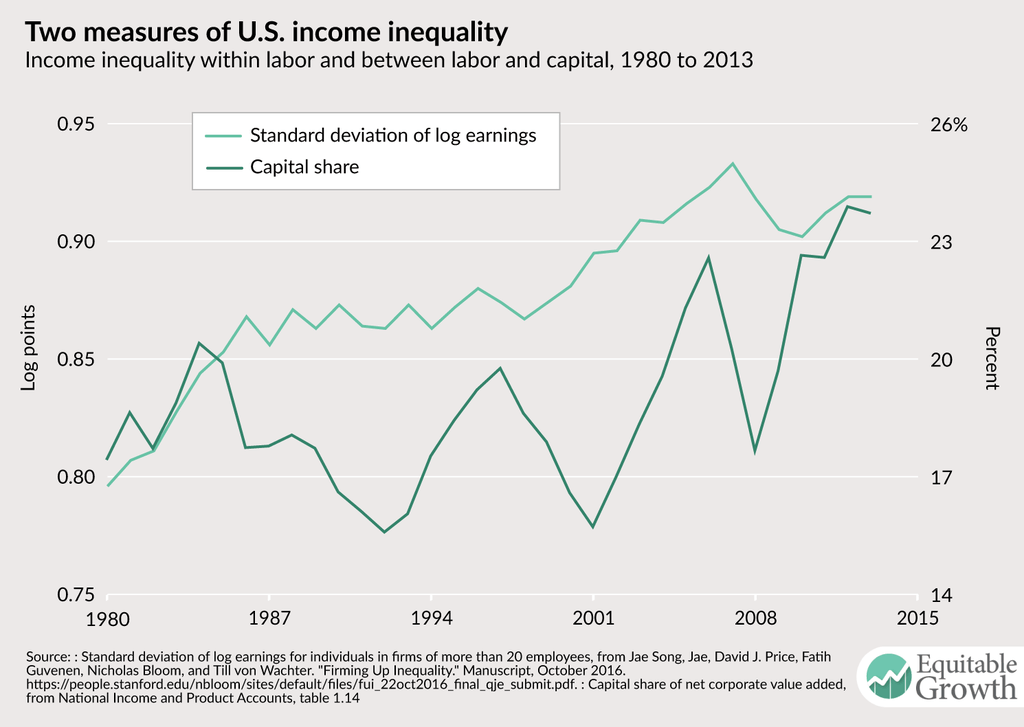

Before turning to that analysis, let us first briefly establish the basis of our inquiry-rising income inequality. Two common measures of inequality in the United States are the standard deviation of log earnings (a measure of inequality within labor income) and the capital share (a measure of inequality between labor and capital). As has been widely documented, both measures have risen since the 1980s.1 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Up until now, most general equilibrium macroeconomic models that were used to evaluate the effects of rising inequality were built under the assumption that the U.S. Federal Reserve would immediately accommodate increases in income inequality by lowering interest rates. Those models accord with the second view-that inequality leads the Fed to lower the cost of capital, encouraging investment, which can lead to an economic boom. In our paper, we show that if we assume that monetary policy has limited willingness or ability to respond to the rise in inequality, then the outcome for GDP looks more concerning.2 Lower consumption lowers employment and individual incomes, feeding back into even lower consumption. Firms disinvest because they anticipate lower employment in the future, and this lowers incomes even further.

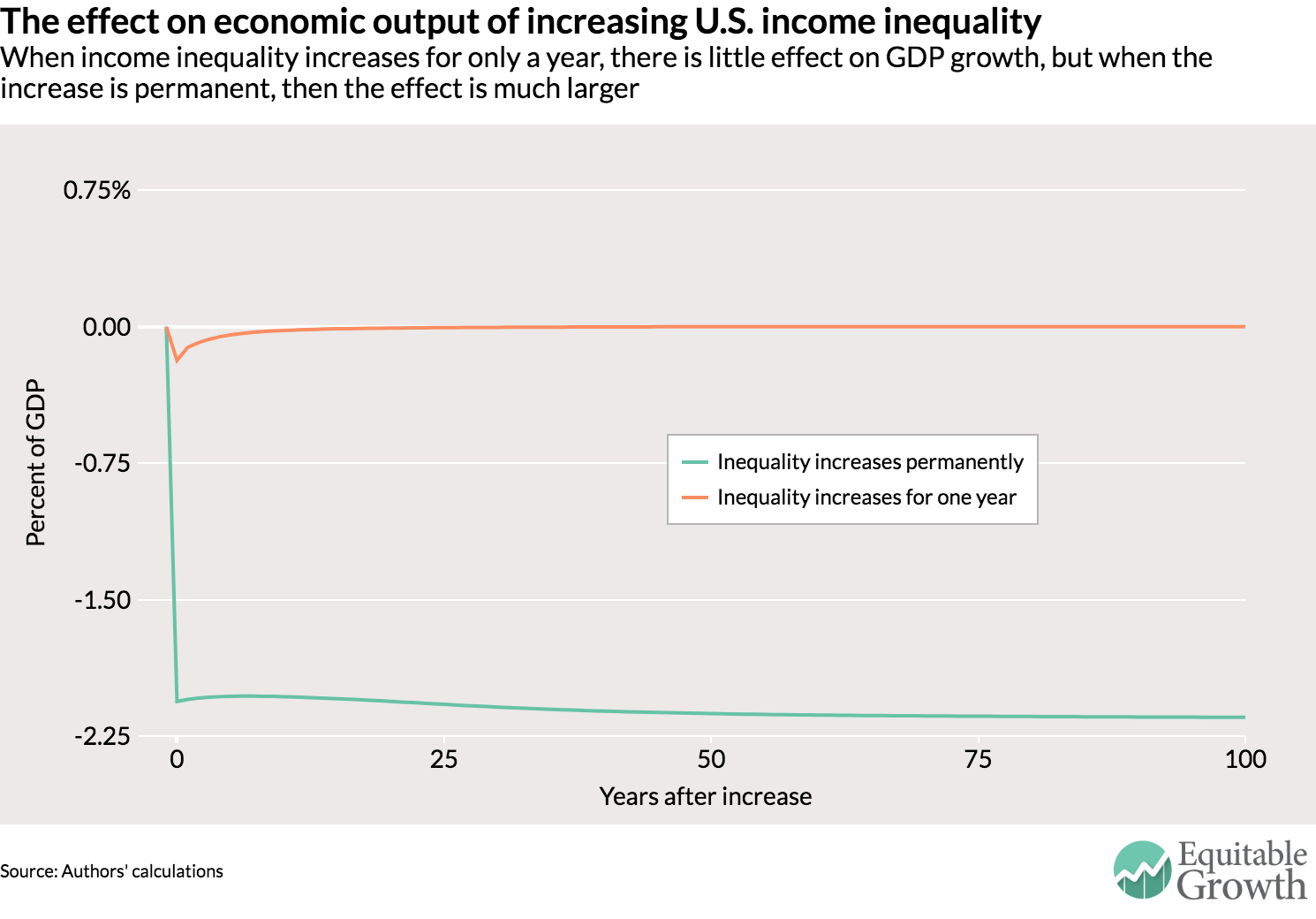

Our new model fits known facts about individuals’ marginal propensities to consume and their saving behavior. We use the model to predict the potential effect of an increase in inequality on economic output, assuming that monetary policy is at the zero lower bound for nominal interest rates, so that it is constrained not to respond to increases in inequality. We show that the key determinant of the effect of inequality on GDP is its effect on asset demand. This is the answer to the question: How much would aggregate wealth increase if we were to artificially hold all other macroeconomic factors such as interest rates and incomes constant? For illustration, we consider two scenarios: one in which inequality rises temporarily-as in the year-to-year fluctuations in the 1990s-and one in which it increases permanently. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

In each case, we assume an increase in inequality of four log standard deviation points (the extent to which the light green line in Figure 1 rose since the 2000s). The orange line in Figure 2 shows that if this increase lasts for only a year, then the effect on output is negative but small-less than two-tenths of a percentage point of GDP. The reason is that marginal propensities to consume are negatively correlated with individual incomes, but this correlation is small-a fact that holds not only in our model but also in datasets that have information about individuals’ incomes and marginal propensities to consume. Hence there is a small effect on asset demand, and a small effect on output.

Our more provocative result is the red line in Figure 2-the case of a permanent increase in inequality. There, our model predicts that the level of output could fall permanently by around 2 percentage points as a result. The reason is that inequality causes individuals’ asset demand to rise permanently by a large amount. In our model, this is because inequality leads individuals to face more risk and volatility in their incomes-and that of their offspring-going forward, leading them to increase savings for precautionary and income smoothing purposes.3 In general equilibrium, employment has to fall by a substantial amount to restore equality between the demand and the supply of assets.

Asset demand, asset supply, and equilibrium interest rates

While this is a stark outcome, our new paper suggests ways in which policy can mitigate the effect of income inequality on aggregate demand. The first is fiscal policy, including government spending and budget deficits. In our model, increases in budget deficits help mitigate the fall in economic output because more government debt increases asset supply.

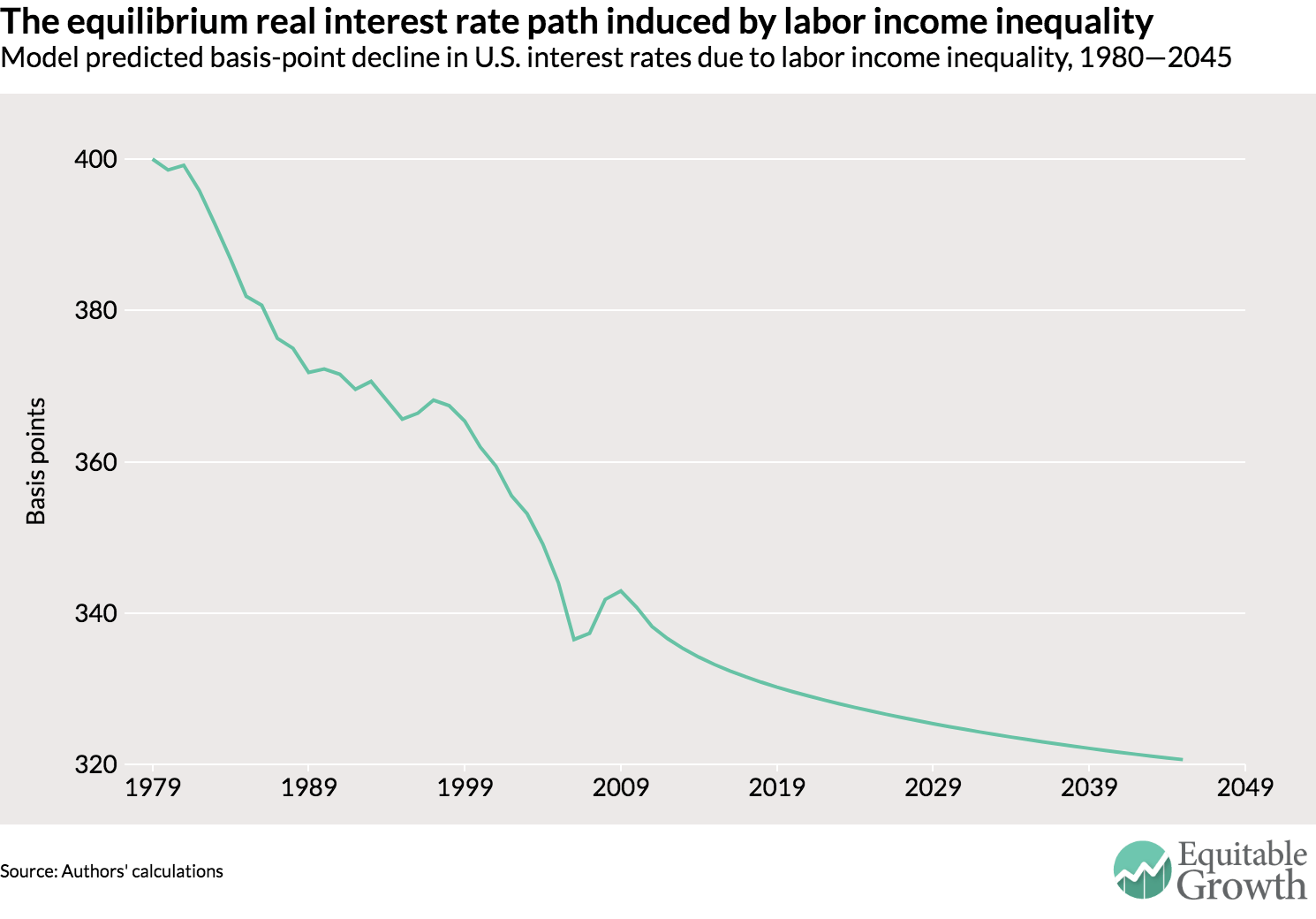

Similarly, monetary policy can respond by lowering interest rates. In fact, the decline in U.S. interest rates that we have observed since the 1980s could have been a response, in part, to rising inequality. Our model predicts what might have been the effect of rising inequality (as in the light green line of Figure 1) on the “equilibrium” or natural interest rate-the interest rate that the Fed needs to set in order to maintain full employment without generating inflation. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Our model suggests a decline of 80 basis points in that equilibrium rate due to rising income inequality, about one-fifth of the 4 percentage point decline documented by Federal Reserve economists Thomas Laubach and John C Williams between 1980 and 2013.4 One implication of our finding is that inequality might have been one of the factors bringing the Fed closer to the zero lower bound of interest rates in the aftermath of the financial crisis beginning in 2008.

Another implication of our demand-supply framework is that of the effect of a rising capital share on equilibrium interest rates and aggregate demand. The dashed red line in Figure 1 shows an increase in that share over the past 30 years. Economists Paul Krugman and Lawrence Summers have argued that this might have contributed to depressing the equilibrium interest rate-or that further increases in market concentration today would be detrimental to aggregate demand.5 In our model, these claims are incorrect. We find that an increase in the capital share always leads to an increase in asset supply because more profits get capitalized into assets that households can trade. This increase in the supply of tradable assets has the exact opposite effect from the increase in asset demand due to higher income inequality: It raises equilibrium interest rates and raises output in liquidity traps.

Policy implications

Our work has a number of important policy implications. First, it suggests that the Federal Reserve and other central banks should keep track of income inequality over time because it influences the decisions that central banks ought to take. Second, our work suggests that not all forms of income inequality have the same effect on equilibrium interest rates: Inequality that raises future risk depresses the natural rate of interest, but technological advances that raise the capital share raise can have the opposite effect. Our model also suggests a more benign view of fiscal deficits than is often assumed in policy discussions because of their beneficial effects on asset supply. A combination of detailed data work narrowing in on the causes of rising income inequality, combined with a model that teases out its aggregate implications, can help the Fed conduct better monetary policy.

Adrien Auclert is an assistant professor of economics at Stanford University and Matthew Rognlie is an assistant professor of economics at Northwestern University. Auclert is a Washington Center for Equitable growth 2015 grantee.