Should-Read: From four years ago. Interesting that in Dan’s view Beltway types have neither the speed of analysis of the money people nor the depth of knowledge of the academics, and in fact have no strengths at all—unless you want to claim that its major additional weakness, groupthink, is also a strength. The major weaknesses of the other two are nicely phrased: money types tending to oversimplify, and academics to overcomplicate: Dan Drezner (2014): What Nick Kristof Doesn’t Get About the Ivory Tower: “Three tribes that dominate the discussion of foreign affairs—academics, Beltway types and money folks… Continue reading “Should-Read: Dan Drezner (2014): What Nick Kristof Doesn’t Get About the Ivory Tower“

Category: Equitablog

Should-Read: Katrine Jakobsen et al.: Wealth Taxation and Wealth Accumulation: Theory and Evidence from Denmark

Should-Read: Katrine Jakobsen et al.: Wealth Taxation and Wealth Accumulation: Theory and Evidence from Denmark: “Denmark… the effects of wealth taxes… on wealth accumulation…

…Denmark used to impose one of the world’s highest marginal tax ates on wealth, but this tax was drastically reduced and ultimately abolished between 1989 and 1997. Due to the specific design of the wealth tax, these changes provide a compelling quasi-experiment for understanding behavioral responses among the wealthiest segments of

the population.We find clear reduced-form effects of wealth taxes in the short and medium run, with larger effects on the very wealthy than on the moderately wealthy. We develop a simple lifecycle model with utility of residual wealth (bequests) allowing us to interpret the evidence in terms of structural primitives. We calibrate the model to the quasi-experimental moments and simulate the model forward to estimate the long-run effect of wealth taxes on wealth accumulation. Our simulations show that the long-run elasticity of wealth with respect to the net-of-tax return is sizeable at the top of distribution. Our paper provides the type of evidence needed to assess optimal capital taxation…

Should-Read: Noah Smith: Rational Markets Theory Keeps Running Into Irrational Humans

Should-Read: Noah Smith: Rational Markets Theory Keeps Running Into Irrational Humans: “To many young people, the idea of efficient financial markets—the idea that…

…in the words of economist Eugene Fama, “At any point in time, the actual price of a security will be a good estimate of its intrinsic value”—probably seems like a joke. The financial crisis of 2008, the bursting of the housing bubble, and gyrations in markets from gold to Bitcoin to Chinese stocks have put paid, at least for now, to the idea that prices are guided by the steady hand of rationality. The theory won Fama an economics Nobel Prize in 2013, but he shared it with Robert Shiller, whose research poked significant holes in the idea decades ago. But believe it or not, there was a time when efficient markets theory occupied a place of honor in the worldview of economists and financial professionals alike….

In “ETF Arbitrage and Return Predictability,” economists David Brown, Shaun Davies and Matthew Ringgenberg take advantage of the way exchange-traded funds are structured. An ETF typically has a designated set of traders called “authorized participants” (APs) who are able to carry out arbitrage between the fund and its underlying assets, whether stocks, bonds or commodities. When the price changes, APs respond by buying and selling the underlying assets, and by either creating or redeeming shares of the ETF, until the two values come back into line. They are, by design, rational arbitrageurs. Generally, an ETF’s APs do a good job of keeping the fund’s value close to the value of the assets it owns. Many studies confirm this. But Brown et al. find that APs’ arbitrage coincides with a deviation of asset values from their fundamentals. When traders other than the APs push around the price, the changes in the prices of the assets tend to reverse themselves over the subsequent months. Anyone watching the APs’ arbitrage trades—which are public record, since they involve the creation and destruction of ETF shares—can then bet that the recent rise or fall in the price of the assets underlying the ETF will be reversed. And make a lot of money. Under efficient markets theory, that’s not supposed to happen….

Efficient markets theory never really fits the facts, but it never quite dies, either.

Should-Read: Paul Krugman: Unicorns of the Intellectual Right

Should-Read: Paul Krugman: Unicorns of the Intellectual Right: “Economics… a field with a relatively strong conservative presence…. [But] trying to find influential conservative economic intellectuals is basically a hopeless task…

…While there are many conservative economists with appointments at top universities, publications in top journals, and so on, they have no influence on conservative policymaking. What the right wants are charlatans and cranks, in (conservative) Greg Mankiw’s famous phrase. If they use actual economists, they use them the way a drunkard uses a lamppost: for support, not illumination. The appointment of Larry Kudlow to head the National Economic Council epitomizes the phenomenon…. Kudlow… is basically a TV personality, whose shtick is preaching the magic of tax cuts, and nothing–not the Kansas debacle, not the Clinton boom, not the strong job creation that followed Obama’s 2013 tax hike–will change his mind. And it’s not just that he’s incurious and inflexible: selling snake oil is his business model, and he can’t change without losing everything. And that’s the kind of guy Republicans want…. If you get a conservative economist who isn’t a charlatan and crank, you are more or less by definition getting someone with no influence on policymakers. But that’s not the only problem….

Conservative economic thought is… [also] in an advanced state of both intellectual and moral decadence…. I’ve written a lot about the intellectual decadence…. Anti-Keynesians refused to reconsider their views when their own models failed the reality test while Keynesian models, with some modification, performed pretty well. By the time the Great Recession struck, the right-leaning side of the profession had entered a Dark Age, having retrogressed to the point where famous economists trotted out 30s-era fallacies as deep insights….

There has been a moral collapse–a willingness to put political loyalty over professional standards. We saw that most recently in the way leading conservative economists raced to endorse ludicrous claims for the efficacy of the Trump tax cuts, then tried to climb down without admitting what they had done. We saw it in the false claims that Obama had presided over a massive expansion of government programs and refusal to admit that he hadn’t, the warnings that Fed policy would cause huge inflation followed by refusal to admit having been wrong, and on and on…. I suspect… it’s… a desperate attempt to retain some influence on a party that prefers the likes of Kudlow or Stephen Moore. People like John Taylor just keep hoping that if they toe the party line enough, they can still get on the inside. But so far this keeps not happening…. And no, you don’t see the same thing on the other side….

Am I saying that there are no conservative economists who have maintained their principles? Not at all. But they have no influence, zero, on GOP thinking. So in economics, a news organization trying to represent conservative thought either has to publish people with no constituency or go with the charlatans who actually matter. And I think that’s true across the board. The left has genuine public intellectuals with actual ideas and at least some real influence; the right does not. News organizations don’t seem to have figured out how to deal with this reality, except by pretending that it doesn’t exist. And that’s why we keep having these Williamson-like debacles.

Weekend reading: “monopsony and March jobs market” edition

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Wealth taxation is an increasingly popular topic of discussion among policymakers as a way to reduce economic inequality. Yet there’s been little empirical research on it. Nisha Chikhale writes about recent research looking at the experience of a Danish wealth tax.

What does a settlement between the National Labor Relations Board and McDonald’s tell us about how the labor market works? Kate Bahn discusses how a joint employer standard is necessary in a world with monopsony.

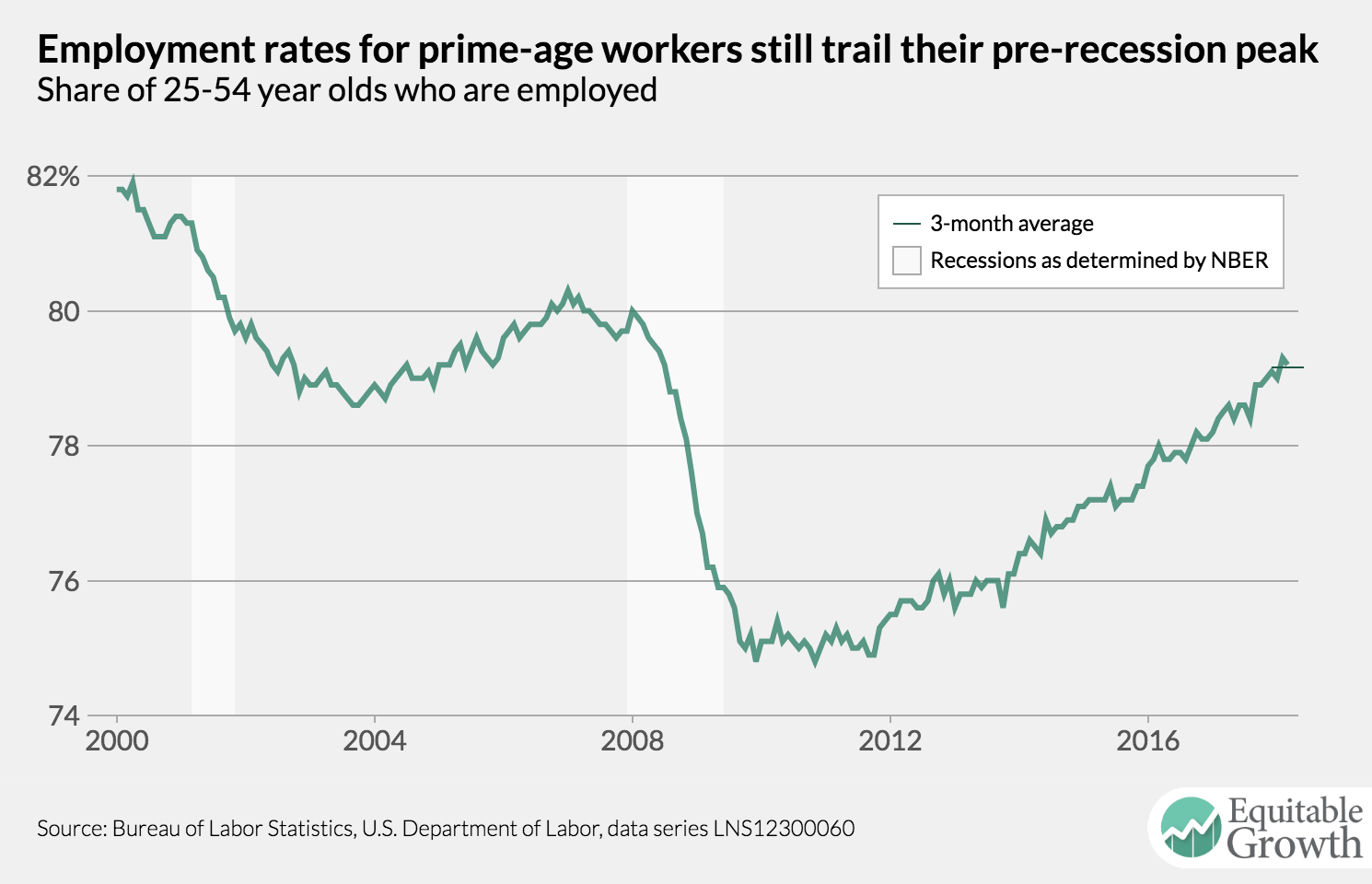

Earlier today the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released new data on the labor market in the month of March. Check out five key graphs chosen by Equitable Growth staff made with the new data.

Links from around the web

The simple “Econ 101” supply and demand theory of the labor market is no longer useful, Noah Smith argues. More and more evidence is showing that employers have considerable power over workers and theories need to reflect that. [bloomberg view]

Speaking of labor market power, Ioana Marinescu of the University of Pennsylvania talks Rob Ferrett about her research on how the declining number of employers is holding down wage growth. [wpr]

Fifty years ago the Kerner Report looked at the systematic inequalities faced by black Americans after the urban riots of the 1960s. Ariel Aberg-Riger took a look at the context for the report and the reaction to it. [citylab]

How do you reduce gender wage inequality? The U.K. government recently required large employers to disclose the gap between average pay for men and women they employ. The Economist notes that this move toward transparency can help reduce gender pay inequality. [the economist]

Looking for a job? U.S. workers who are employed are more likely to end up with an offer with higher wages and benefits than an unemployed worker and also more likely to receive an offer unsolicited. That’s according to data from several economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. [Liberty Street Economics]

Friday figure

Figure is from “Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: March 2018 Report Edition”

Now That John Williams Is President of the New York Fed, He Really Should Convene a Blue Ribbon Commission on What the Inflation Target Should Be

From June 2017: Fed Up Rethink 2% Inflation Target Blue-Ribbon Commission Conference Call: I hear four arguments for not changing the 2%/year inflation target, even though pursuing that target found us in a situation where monetary policy was greatly hobbled in its ability to manage the economy for a solid decade. And, as best as I can evaluate them, all four of these arguments seem to me to be wrong. They are:

-

The Federal Reserve, even at the zero lower bound, has powerful tools sufficient to carry out its stabilization policy tasks….

-

The problem is not the 2%/year target but rather pressure on the Federal Reserve… from substantial numbers of economists and politicians practicing bad economics and motivated partisan reasoning….

-

A higher inflation rate would bring shifting expectations of inflation back into the mix, distract people and firms from their proper task of calculating real costs and benefits to worry about monetary policy, and make monetary policy management more complicated….

-

The Federal Reserve needs to maintain its credibility, and if it were to even once change the target inflation rate, its commitment to any target inflation rate would have no credibility….

Should-Read: Mary Daly: Raising the Speed Limit on Future Growth

Should-Read: The eminent and brilliant Mary Daly is one of the people on the shortest of my short lists of people who would be a good next president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Here she is talking in Phoenix, AZ: Mary Daly: Raising the Speed Limit on Future Growth: “Why aren’t American workers working?…

Some of the drop owes to wealthier families choosing to have only one person engaging in the paid labor market (Hall and Petrosky-Nadeau 2016). And I emphasize paid here…. Some of the lost labor market participation seems related to having the financial ability to make work–life balance choices. Another factor… is ongoing job polarization that favors workers at the high and low ends of the skill distribution…. Our economy is automating thousands of jobs in the middle-skill range, from call center workers, to paralegals, to grocery checkers…. These pressures on middle-skilled jobs leave a big swath of workers on the sidelines, wanting work but not having the skills….

The final and perhaps most critical issue…. We’re not adequately preparing a large fraction of our young people for the jobs of the future…. By 2020, for the first time in our history, more jobs will require a bachelor’s degree than a high school diploma (Carnevale, Smith, and Strohl 2013)…. In 2016 only 37% of 25- to 29-year-olds had a college diploma (Snyder, de Brey, and Dillow 2018)…. So where should we focus our efforts when it comes to getting more young people into college? One place to start is in working to equalize educational attainment across students of different races and ethnicities…. Given the important role that education plays… equalizing… educational attainment across these groups has big benefits….

The really good news is that education is generally a win–win, beneficial to individuals and to taxpayers. We know that those with a college degree are much more likely to become top earners during their career, regardless of their financial background (Daly 2012; Daly and Bengali 2013, 2014; and Daly and Cao 2015). They have lower unemployment rates, and they’re less likely to become unemployed during a recession. And while there’s no doubt the cost of college is a strain for many, the average time it takes to recoup that cost is 10 years (Abel and Deitz 2014). This means that, relative to many other investments, education pencils out, even if graduates don’t go on to earn top salaries. For taxpayers the math is even more straightforward. A detailed study by the OECD shows that college is a great investment for taxpayers (OECD 2017). The costs paid to educate are more than covered by increased productivity, longer and more stable work lives, and higher tax revenues from graduates…. Education is incentive compatible, good for everyone involved…

Should-Read: Larry Summers: No, “Obamasclerosis” wasnt a real problem

Should-Read: I need to figure out why the usually-reliable Greg Ip has started giving more credence than he should to the claims of Trump hacks and flacks like Kevin Hassett, Larry Kudlow, Peter Navarro, and their ilk: Larry Summers: No, “Obamasclerosis” wasnt a real problem: “The Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip… finds credible… claims that President Barack Obama’s policies… materially slowed economic growth…

… even though Ip acknowledges that the CEA’s assertions regarding magnitudes are likely exaggerated.

The CEA’s thesis is that a wave of tax and regulatory policies reduced both workers’ incentives to work and businesses’ incentives to invest, leading to slower economic growth than would otherwise have been achievable…. At least three broad features of the economic landscape make the CEA’s view an unlikely explanation for disappointing economic growth….

- The dominant reason for slow growth has been what economists label slow “total factor productivity” (TFP) growth…. There is no basis for supposing that levels of labor input or capital are less than one would expect given the magnitude of the Great Financial Crisis…. This suggests the lack of importance of the various factors adduced by the… [Trumpists’] report….

The biggest surprise of the last few years has been the remarkably low rate of inflation even as the unemployment rate has reached 4 percent….. If, as the CEA believes, our slow economic growth is a result of too little supply of labor and capital, one would expect surprisingly high, rather than surprisingly low, inflation as demand growth collided with constricted supply…. The secular stagnation hypothesis that emphasizes issues on the demand side would predict exactly the combination of sluggish growth, low inflation and low capital costs that we observe….

The… thesis… that capital has been greatly burdened in recent years by onerous regulation, high taxes and a lack of availability of labor… is belied by the behavior of the stock market and of corporate profits…. The observation that share buybacks appear to be the largest use of the proceeds from the Trump tax cuts points in the same direction. Costs of capital have not been responsible for holding back investment in the United States in recent years.

If the “Obamasclerosis” theory does not fit the facts of slow growth in recent years, what are its likely causes?… My guess is… hysteresis effects from the financial crisis and associated recession, reduced application of innovation in the economy in recent years, and possibly the adverse effects of rising monopoly power and diminishing competition…

It is puzzling. Kevin Hassett’s arguments seem transparently false—claims on the other of magnitude as “supply curves slope up” and “burdensome regulations raise stock prices”. They are not the type of thing that I would have expected anyone working for the Wall Street Journal news pages to validate.

It is the case that some Wall Street Journal insiders claim that editor Gerard Baker was a catastrophic choice: that he is a Trumpist true believer who has created a pre-1990 Eastern European atmosphere at the news pages of the Journal as he has decided to light the news pages’ credibility as an information intermediary on fire in an attempt to make Trump look less bad in relative perspective by making everybody else look as bad as possible.

Others say that the pressure is coming from Rupert, James, and Lachlan Murdoch and that Baker is trying hard to do as good a job as possible under the circumstances.

Should-Read: Mark Antonio Wright: Oklahoma’s Teachers & Education Funding Issues

Should-Read: Read National Review before… well, before today… about Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin, and you read things like “There’s still quite a bit of experienced managerial and legislative talent walking through the lobby of Trump Tower these days… Oklahoma governor Mary Fallin…” and “A Mama Grizzly Wins in the Sooner State”. All that is now, as they say, inoperative. But surely NR could have given its loyal readers a heads-up sometime in the past eight years that MISTAKES WERE MADE?: Mark Antonio Wright: Oklahoma’s Teachers & Education Funding Issues: “No reasonable examination of the facts can avoid laying blame at the feet of Republican governor Mary Fallin…

…Once a rising conservative star, Fallin served three terms as Oklahoma’s lieutenant governor and two terms in the U.S. House before she was elected to the governorship in the GOP-wave year of 2010, accompanied by big Republican majorities in both houses of the legislature. The ensuing years, however, have seen a constant stream of budget and funding missteps…. Government in Oklahoma needs deep reform. If the states are meant to be, in our federal system, sovereign “laboratories of democracy,” then Oklahoma’s leaders should realize that their current experiment is failing…. Four-day school weeks, classrooms with 40 kids, and students forced to sit on the floor is no one’s idea of a successful educational environment. Conscientious Okies should get to work…

McDonald’s, monopsony, and the need for joint employer standards

McDonald’s Corp. is involved in a case with the National Labor Relations Board regarding the company’s responsibility under the so-called joint employer standard for the firing of workers at their franchises for labor organizing under the “Fight for Fifteen” campaign to raise the minimum wage. The corporation reached a resolution with the NLRB, and there will be a settlement hearing on April 5. The settlement, however, is a result of the Trump administration’s vacating Obama administration standards for joint employment—standards that held a corporation responsible for the labor decisions and outcomes at its agency franchises. How the resolution is worded when it’s unveiled tomorrow may well determine whether rising income inequality in the United States can be addressed through collective bargaining in one of the most important industries for low-wage workers.

The joint employer standard is significant for labor organizing because it is easier to unionize across establishments within the same company than at individual establishments one by one. More specifically, recognizing this standard could help address wage stagnation resulting from the dual effects of increasing market concentration and so-called job search frictions in the fast-food industry, which can lead to depressed wages across the industry alongside the fissuring of the workplace—similar to the franchising model that divides workers within a single corporate business model. These twin forces contribute to stagnating wages, including a federal minimum wage that has not kept up with inflation, and decreasing worker power.

Economists have a term for this kind of situation in the marketplace and in the labor market. It’s called monopsony—originally conceptualized by Joan Robinson in The Economics of Imperfect Competition in 1933 as a labor market with only one employer who holds complete sway over the wages it offers to its workers rather than the competitive market determining the going wage rate. More recently, job search theory demonstrates that search frictions result in monopsonistic conditions, where a small group of employers exert wage-setting power in an uncompetitive labor market. Recent research supports the idea that low-wage labor markets show signs of lack of competition, resulting in persistent low pay, which in turn indicates that the U.S. labor market can bear an increase in the federal minimum wage and also more clout for workers to collectively bargain for their wages.

Monopsony theory predicts the situation facing workers at McDonald’s franchises today. But to understand more fully why joint employer standards are important for industries such as fast food, we need to understand the most recent data-driven evidence of monopsony and what the theory of monopsony tells us about collective bargaining. Let’s turn first to a recent working paper by economists Arin Dube at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Alan Manning at the London School of Economics, and Suresh Naidu at Columbia University. They find that the lack of competition in labor markets help explain why wages are often “bunched” around round numbers similar to how they are today around the current minimum wage in the fast-food restaurant industry. Prior research by Dube, along with his colleague Doruk Cengiz at the University of Massachusetts, Atilla Lindner at the Institute of Labor Economics, and Ben Zipperer (now at the Economic Policy Institute) also found that this kind of bunching around the minimum wage, common in the fast-food industry, was prevalent.

Dube, Manning, and Naidu in their recent paper provide evidence that many markets have a combination of imperfect competition, as in monopsony, and imperfect firm optimization, which is when firms aren’t earning the maximum possible profits. Competitive markets economic theory explains bunching as “left-digit bias,” where workers (or consumers) believe a wage (or a consumer good price) of $10 is much higher than a wage (price) of $9.90. Dube, Manning, and Naidu use administrative unemployment insurance data from Washington and Minnesota, two states that collect detailed hourly information in their payroll taxes, to estimate the extent to which bunching is explained by this left-digit bias. They also examine labor market competition—measured by labor supply elasticity, which estimates the degree of monopsony—and employer mis-optimization, which is how much profit employers are willing to give up in order to pay their employees a round number. Their study explicitly examines wage bunching at $10, which is within the universe of pay among restaurant workers.

With limited evidence of worker left-digit bias, the three economists find a trade-off between employer market power and optimization frictions—when employers exert market power and thus are able to maintain subcompetitive wages at a “bunched” level. When there are optimization frictions, firms give up profits in order to maintain wages at a bunched level. This kind of monopsony in low-wage work is further supported by a 2010 study by Dube, T. William Lester at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Michael Reich at the University of California, Berkeley. They found that minimum-wage increases did not decrease employment levels in restaurant employment, as would be predicted under the assumption of competitive markets. That 2010 study estimated the effect of an increase in the minimum wage across contiguous counties using the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages. The three researchers found that restaurant workers in those counties that had a minimum-wage increase experienced increases in their incomes with no discernible disemployment effects.

Further work by Dube, Lester, and Reich from a 2014 study using Quarterly Workforce Indicators examined the underlying dynamics behind this earlier finding. That study noted that if there were search frictions in a labor market, as described by Alan Manning, then increases in the minimum wage would reduce job-to-job transitions. Using information on the duration of nonemployment in the industry for restaurant workers and teen workers—two common minimum wage groups—they find this to be the case. The authors note these findings are “rough,” but they are able to roughly estimate that job-to-job transitions account for more than half of separations (economics-speak for leaving a job) for restaurant workers. The authors find that an increase in the minimum wage of 10 percent reduces the turnover of restaurant workers by 2.1 percent, which means workers’ tenure increased, and did not result in less employment.

Indeed, one of the important implications of these findings as they relate to the theory of monopsony is that employers can bear higher wages such as those induced by government increases in the minimum wage. The same monopsonistic findings hold for collective bargaining, too. When individual employers face an upward sloping supply-of-labor curve that falls below their marginal-cost curve, they pay less and employ fewer workers than would be predicted by a competitive model. If wages were collectively bargained to go higher along the labor supply curve, then employers could bear wage increases up to the point where supply and demand meet. Unionization, then, among fast-food workers can lead to the wage and employment levels that would be predicted by such a supply-demand equilibrium in a competitive model.

Because of the structure of fast-food employment generally, and the business model of McDonald’s in particular, workers may face low wages due to monopsonistic forces, yet they are constrained in their ability to bargain collectively for wages that would correspond to their productivity. Joint employer responsibility is a key tool for workers to organize across establishments so they can garner the power through collective action needed to balance the wage-setting power at individual establishments, both corporate-owned and franchised.