This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Quite a few researchers have had their eyes on the decline in the U.S. labor force participation rate since 2000. A number of factors seem responsible for the decline, but a new report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development highlights one policy that could help reverse the trend: paid leave. Bridget Ansel looks at the promise of the policy.

With research showing the low level of intergenerational mobility in the United States, policymakers and researchers are looking for ways to boost mobility for children from low-income backgrounds. Seems as though simple cash transfers to parents may help, Bridget Ansel reports.

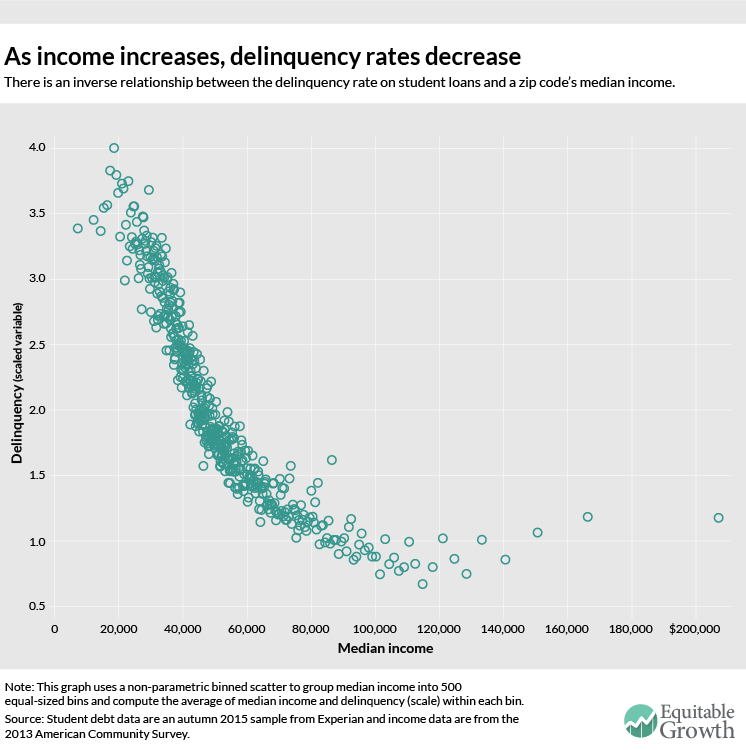

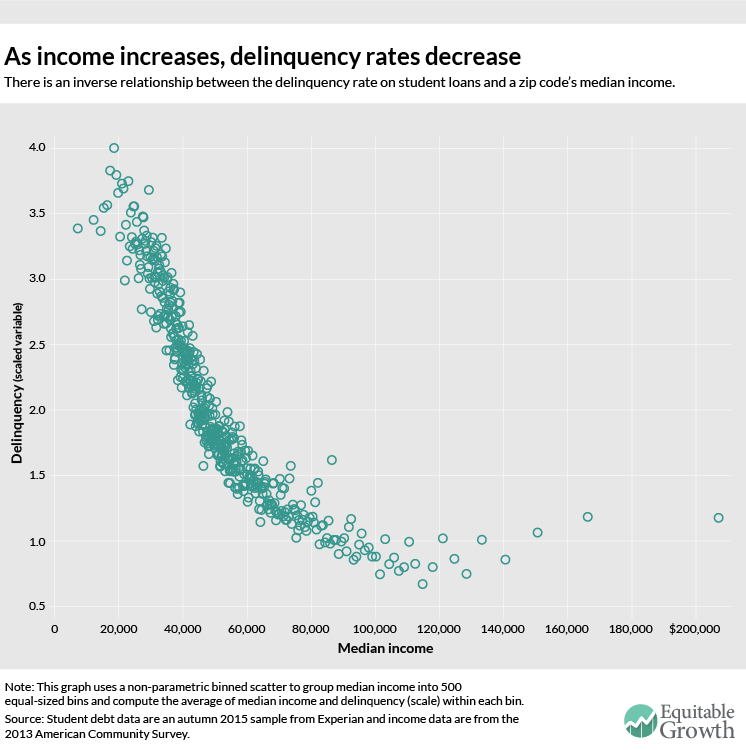

The explosion in student debt in the United States over the past decade has been widely reported and has spurred research into the consequences of this phenomenon. Marshall Steinbaum and Kavya Vaghul share their analysis of a new dataset on the geography of student debt.

Universal prekindergarten has become an increasingly popular policy proposal for dealing with low levels of economic mobility, slowing economic growth, and high levels of inequality. In a new report, Robert Lynch and Kavya Vaghul calculate the costs and benefits of a nationwide high-quality universal prekindergarten program.

As for those costs and benefits, Austin Clemens, Robert Lynch, and Kavya Vaghul created interactive maps and graphs to show the state-by-state effects of a universal pre-K program.

The global corporate income tax system has a problem with “stateless income” and profit shifting across borders. The Group of 20 and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development recently released new proposals for combating this problem. They are good first steps to bring more corporate profits into the light, but they may not be enough.

Inequality is not a monolithic concept. While the inequality of wages among U.S. workers has increased, another form of inequality—the share of income going to labor instead of capital—has declined. Which trend has contributed more to rising household income inequality? Looks like wage inequality. But who knows about the future.

Wage and earnings growth in the United States has been far from strong since the Great Recession. But how much do these trends differ by what kind of job a worker has? Austin Clemens built a few interactive graphs to let you see the trends for yourself.

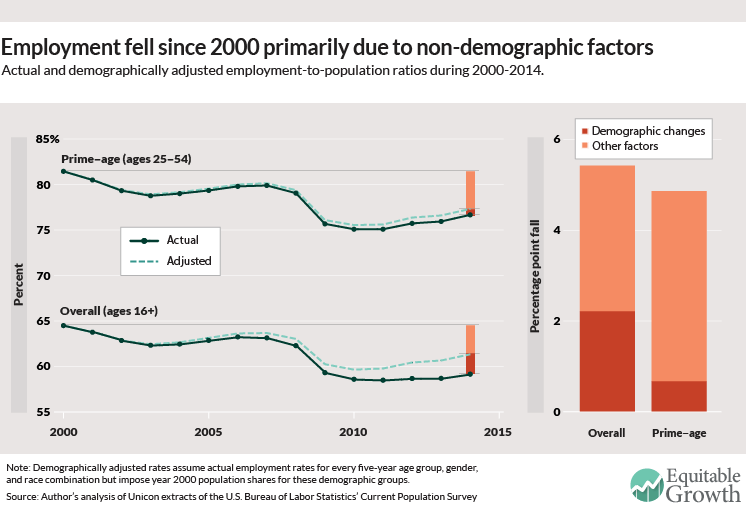

The U.S. unemployment rate has been on the decline for several years now, but the employment rate has been essentially stagnant. Some analysts argue that the aging of the workforce can explain most of this decline, but Ben Zipperer shows that the decline is due primarily to non-demographic reasons.

Links from around the web

For many years, the predominant explanation for the rise in income inequality in the United States was a hypothesis called “skill-biased technological change.” In essence, increasing demand for skills supposedly pushed up the wages of skilled workers. Paul Krugman argues, however, that this is no longer a good explanation and that the focus should shift to changes in market power. [nybooks]

Increased intergenerational transmission of wealth through inheritance is one of the concerns about rising wealth inequality in the United States. But we can’t look at that concern in isolation—wealth inequality and inheritance in the United States can’t be separated from race, says Mel Jones. [the atlantic]

Economists always assumed that nominal interest rates could only go as low as zero percent. But the last few years have shown that if there is a lower bound for interest rates, it isn’t at zero. Neil Irwin looks at what negative interest rates being the new normal means for the economy. [the upshot]

No one will deny that it’s difficult to project what will happen to the economy, or even parts of it. But when predictions go south, they can provide good learning opportunities. Betting that demographics would predict housing prices, for example, ended up being a bad idea, as Matthew C. Klein shows. [ft alphaville]

Productivity usually results in economies increasing the amount of capital per worker. But in the United States, capital per worker seems to have declined from 2011 to 2013. Dietz Vollrath digs into the data to try to understand why capital investment per capita declined. [growth economics]

Friday figure

Figure from “An introduction to the geography of student debt” by Marshall Steinbaum and Kavya Vaghul.