This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Thomas Piketty caused a bit of a stir within economics when he called for a 3 percent global wealth tax in his book “Capital in the Twenty-First Century.” But now, more than a year later, parts of the economics profession seem to be engaging more with the idea of a tax on wealth. One session at the Allied Social Science Associations annual meeting last week is a good example of this trend.

Wage and earnings inequality can be very abstract concepts and seem detached from the real world at times. A “worker at the 30th percentile” isn’t something we all naturally think of. In a new interactive, Kavya Vaghul, Austin Clemens, and John Schmitt explore how earnings inequality looks once we consider the race, gender, and occupations of workers.

The vast majority of the studies on the effects of raising the minimum wage investigate how it affects workers. But it influences outcomes for firms as well. A new study looks at what happens to the flow of firms after a minimum-wage hike, with quite interesting results.

Speaking of the behaviors of firms, the declining business startup rate in the United States has increasingly become a subject of worry. And not only are there fewer startups, but they aren’t growing as quickly as before. New research indicates it’s because firms are hiring less once they become more productive.

Tuesday night, President Obama delivered his final State of the Union address, in which he noted the improvements in the U.S. economy. But as Heather Boushey notes, the economy is a bit like an inkblot in a Rorschach test these days.

Many studies of intergenerational mobility focus on earnings, particularly for men, due to data issues. But a new study, highlighted by Bridget Ansel, looks at how educational attainment is passed along three generations of women.

The D.C. Council is currently considering a bill that would implement a universal paid leave system in the District. The council met on Thursday to consider the legislation and Heather Boushey testified on the economics of paid leave.

The third installation of Equitable Growth’s “History of Technology” series was published this week. Adelheid Voskuhl of the University of Pennsylvania takes a look at how the transformation of the engineering profession during the Second Industrial Revolution can inform the changes we’re seeing during the “Fourth” Revolution.

Links from around the web

Prominent venture capitalist Paul Graham recently published an essay about inequality and its relative merits that received a considerable amount of feedback. He argues that inequality is a necessity for economic growth and innovation. Jim Tankersley writes that the economics research is starting to show perhaps the exact opposite is true. [wonkblog]

In a continuing series about the influence of changing demographics on the economy, Matthew Klein highlights four major reasons to believe that demographics are not destiny when it comes to inequality, the bargaining power of labor, and inflation. [ft alphaville]

The Federal Reserve has started its “normalization” process of raising interest rates, but the pace has yet to be determined. Carola Binder argues the central bank should be aware of the ways its actions affect inequality and how inequality affects how monetary policy is conducted. [quantitative ease]

Labor market statistics are necessarily aggregations, and that includes when we try to slice statistics like the employment rate by age. But according to analysis by Josh Lehner, if you are under 55, you’re less likely to have a job today than a worker the same age in 2000. [oregon economic analysis]

The declining labor force participation rate in the United States has been one of the most important economic trends of the last several years. The causes of the trend are multifaceted and economists are still untangling them. But why do people say they are out of the labor force? Timothy Taylor investigates. [conversable economist]

Friday figure

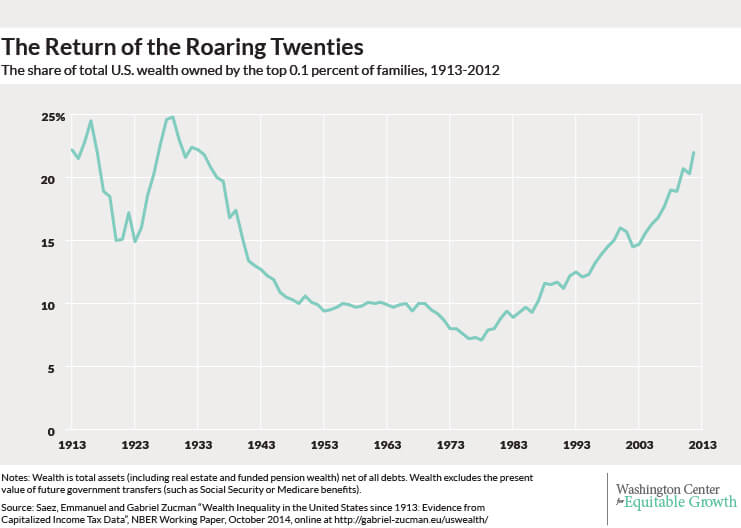

Figure from “Exploding wealth inequality in the United States” by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley.