- : The Protestant Reformation, Economic Institutions, and Development

- : Can We Get Rich by “Doing Business” Better?

- : Brownback’s Kansas Experiment a Failure

- : The Political Legacy of American Slavery

- Comment of the Day: Tacitus “It belongs to human nature to hate those you have injured…”

- Weekend Reading: Alexis de Tocqueville: Book II Chapter 20 The Aristocracy of Manufacturers

- Weekend Reading: Paul Krugman (2015): Annoying Euro Apologetics

Category: Equitablog

Must-Read: Jeremiah Dittmar and Ralf R Meisenzahl: The Protestant Reformation, Economic Institutions, and Development

Must-Read: : The Protestant Reformation, Economic Institutions, and Development: “Origins of growth: How state institutions forged during the Protestant Reformation drove development…

…Throughout history, most states have functioned as kleptocracies and not as providers of public goods. This column analyses the diffusion of legal institutions that established Europe’s first large-scale experiments in mass public education. These institutions originated in Germany during the Protestant Reformation due to popular political mobilisation, but only in around half of Protestant cities. Cities that formalised these institutions grew faster over the next 200 years, both by attracting and by producing more highly skilled residents.

The state can be a rent-extracting institution or a provider of public goods. What happens when the state becomes the provider of public goods?

Recent research suggests that where states have greater capacity to provide public goods, economic outcomes may be superior (Besley and Persson 2009, 2010, Acemoglu et al. 2015). The economics literature has emphasised expansions of state capacity that emerged for geostrategic and military reasons in European history ‘from above’.

In a recent paper (Dittmar and Meisenzahl 2016), we study a unique experiment that shifted legal institutions at the local level – the institutional public goods programme of the Protestant Reformation in Germany.

The institutions that we study were city-level laws that established Europe’s first large-scale experiments with mass public education and significantly expanded the social welfare bureaucracies and state capacities of cities. These legal institutions established a fundamental innovation in funding and oversight for municipal activities – the ‘common chest’, a literal box of funds used to support public services. Significantly, the adoption of these institutions reflected popular political mobilisation.

In our research, we study the local variation in institutions and answer three interrelated questions:

- How did these innovations shape development?

- Why did some but not all cities adopt these institutions?

- What was the political process driving these transformations in German society?

Mapping an institutional upheaval: The local adoption of these new legal institutions was highly variable. In fact, fewer than 55% of cities that adopted Protestantism established legal institutions to support the provision of public goods. We observe variation across neighbouring cities in the same territory, subject to the same territorial lord.

The impact of institutions on long-run development: We test the hypothesis that cities with city-level Reformation laws by 1600 subsequently grew relatively quickly. Our first finding is that cities that adopted the Reformation institutions grew to be at least 25% larger in 1800 than observably similar cities. In contrast, we find no variation in growth associated with Protestant religion conditional on public goods institutions.

Historical evidence suggests that migration drove city growth in pre-industrial Europe (de Vries 1986, Bairoch 1991, Reith 2008). Existing quantitative evidence on migration is limited. We collect novel microdata on the migration and local formation upper tail human capital (Mokyr 1999, Squicciarini and Voigtlander 2015). Our data, drawn from the Deutsche Biographie, comprise thousands of the most important cultural and economic figures in German history between 1300 and 1800 – jurists, merchants, writers, artists, composers, and educators. We use the data to document the human capital response to institutional change.

Figure 2 shows how migration responded to institutional change by plotting the number of upper tail human capital migrants observed in cities that adopted public goods laws, cities that became Protestant but did not formalise public goods provision, and Catholic cities. These cities were attracting similarly small numbers of migrants before the Reformation, which is marked by the vertical line at 1518. A large shift in migration towards cities with public goods institutions appears in the 1520s, as legal reforms were passed. This gap persisted over the next 200 years and notably was driven by differences in migration from small towns to cities, not by a ‘brain drain’ from less to more desirable cities.

We similarly find that cities with public goods institutions began producing more upper tail human capital starting after 1520. We find no differences in the local formation of upper tail human capital before the Reformation and 50-200% higher formation of upper tail human capital after the Reformation when we compare cities with laws supporting public goods provision to cities without these institutions.

Why not all cities adopted public goods institutions: The Protestant Reformation was both a religious revival movement and an anti-corruption movement with an institutional agenda. The institutional agenda was designed to expand the provision of public services.

Popular political mobilisation drove the Protestant Reformation. Local elites and city councils initially resisted the introduction of Protestantism (Cameron 1991, Dickens 1979). Civil disobedience and unrest pushed policymakers to meet citizen demands and pass laws establishing the public goods institutions of the Reformation. Differences in institutional outcomes across municipalities reflected differences in local preferences and in political mobilisation, which varied across cities even within the same territory.

How plague outbreaks shifted politics and institutions:The very features that led some communities to welcome religious innovation and to mobilise in support of institutional change may have had independent implications for economic development.

To untangle cause and effect, we study how plague outbreaks in the critical juncture of the early 1500s shifted local politics and pushed otherwise similar cities towards institutional change.

During plague outbreaks incumbent wealthy elites typically fled their home cities or died, reducing their political power (Dinges 1995). Following plague outbreaks, migration into cities increased, changing the composition and politics of the population (Isenmann 2012). During these periods, suffering was acute and civic order could break down. Before the Reformation, plagues led to religious innovations within Catholicism – such as the development of penitential rituals and marches and the construction of church altars to ‘plague saints.’

During the Reformation – with the introduction of political and religious competition – plagues suddenly operated as institutional shifters. Plagues operated as institutional shifters not only because they caused extreme suffering, but specifically because Protestants and Catholics were differentiated in the market for religion in their institutional programme and teachings regarding the plague.

We study local plague outbreaks in the early 1500s as a source of plausibly random variation in institutional change. The intuition is that plagues that hit the generation in place when the Reformation broke across German cities were random, conditional on long-run levels and trends. In the data, we find that an additional plague in the early 1500s increased the probability of adopting the new legal institutions by 10-25%.

To illustrate the research design, Figure 3 shows the timing of plague outbreaks in select cities. In Figure 3, we highlight the period 1500 to 1522, which serves as the baseline period that we use to study the implications of the plague for institutional change.

To document the unique relationship between plagues in the early 1500s, institutions, and growth, we study plague outbreaks across the entire period from 1400 to 1600. Figure 4 plots the point estimates from rolling instrumental variable (IV) regressions that study log city population in 1800 as the outcome. We estimate these regressions shifting the time period, which we use as the plague exposure IV for institutional change year-by-year. There is no significant relationship between plagues across the 1400s and subsequent institutional change and the 2SLS estimates of the population growth impact of induced variation in institutions are insignificant. In the early 1500s, these relationships change. With the introduction of religious and political competition, we see plague exposure being activated as an institutional shifter with development consequences in the early 1500s.

Conclusion: During the Protestant Reformation, some but not all German cities adopted new municipal legal institutions. These institutions expanded state capacity and established public schooling. The cities that adopted these institutions grew faster over the next 200 years. These cities attracted and produced more upper tail human capital individuals and embarked on more dynamic development trajectories. Cities that adopted Protestantism but did not formalise public goods institutions in law had no similar advantage.

Our results strongly suggest that human capital was not dormant, waiting to be ‘activated’ during the Industrial Revolution – it was instead a fundamental driver of growth over the early modern period. More broadly, our findings suggest that the Protestant Reformation was a canonical model of the emergence and implications of state capacity driven by political movements that challenge elites.

Authors’ note: The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

References:

Acemoglu, D, C Garcia-Jimeno and J Robinson (2015) ‘State capacity and economic development: A network approach’, American Economic Review, 105: 2364-2409.

Bairoch, P (1991) Cities and economic development: From the dawn of history to the present, University of Chicago Press.

Besley, T and T Persson (2009) ‘The origins of state capacity: Property rights, taxation, and politics’, American Economic Review, 99: 1218-44.

Besley, T and T Persson (2010) ‘State capacity, conflict, and development’, Econometrica, 78: 1-34.

Cameron, E (1991) The European Reformation, History Reference Center, Clarendon Press.

De Vries, J (2006) European Urbanization, 1500-1800, Routledge.

Dickens, A (1979) ‘Intellectual and social forces in the German Reformation’, in Mommsen, W (ed), Stadtburgertum und Adel in der Reformation, Ernst Klett.

Dinges, M (1995) ‘Pest und Staat: Von der Institutionengeschichte zur Sozialen Konstruktion?‘, in Dinges, M and T Schilch (eds) Neue Wege in der Seuchengeschichte, Franz Steiner, Stuttgart.

Dittmar, J and R Meisenzahl (2016) ‘State capacity and public goods: Institutional change, human capital, and growth in early modern Germany’, Working paper, LSE Centre for Economic Performance and Federal Reserve Board.

Isenmann, E (2012) Die Deutsche Stadt im Mittelalter 1150-1550, Bohlau.

Mokyr, J (2009) The enlightened economy: An economic history of Britain, 1700-1850, New Economic History of Britain, Yale University Press.

Reith, R (2008) ‘Circulation of skilled labour in late medieval Central Europe’, in Epstein, S and M Prak (eds) Guilds, Innovation and the European Economy, 1400-1800, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Squicciarini, M and N Voigtlander (2015) ‘Human capital and industrialization: Evidence from the age of Enlightenment’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130: 1825-83.”

Must-Read: Dietrich Vollrath: Can We Get Rich by “Doing Business” Better?

Must-Read: : Can We Get Rich by “Doing Business” Better?: “Below I’m going to get to the gory details of why the Doing Business (DB) indicators generally suck…

…But let me start with this note. The DB index [John] Cochrane uses is a ‘distance to the frontier’ index. Meaning you get a number that tells you how close to best practices in business conditions a country gets. If you are at the best practices in all categories, you’d get a 100. Cochrane says, and I quote, ‘If America could improve on the best seen in other countries by 10%, a 110 score would generate $400,000 income per capita…’. Stew on that for a moment. Think about how that DB frontier index is constructed.

Cochrane went there. He said it could go to 11….

[…]

It Gets Worse: In the follow up post, Cochrane appeals to a graph from my textbook with Chad Jones… the relationship of an index of ‘social infrastructure’ and TFP…. I calculated it, graphed it, and stuck it on the slide that Cochrane linked to. I simply scaled and averaged the 6 different components of the World Bank’s governance indicators, much like the DB index. It has all the issues I described above, except worse. This figure tells us very little. Which is why in the book we immediately say that you cannot infer anything causal from it, and then go on to talk about some of the better studies done looking at specific institutions and their effects on economic outcomes…

Must-Read: Justin Wolfers: Brownback’s Kansas Experiment a Failure

Must-Read: : On Twitter:

Its time to declare Brownbacks Kansas experiment a failure: https://t.co/6R7dHrPk1K

More: https://t.co/DP4QLSkQi2 pic.twitter.com/lUgLMa38Ch— Justin Wolfers (@JustinWolfers) April 26, 2016

Must-Read: Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen: The Political Legacy of American Slavery

Must-Read: Fruit of a badly-poisoned tree…

: The Political Legacy of American Slavery: “We show that contemporary differences in political attitudes across counties in the American South…

…in part trace their origins to slavery’s prevalence more than 150 years ago. Whites who currently live in Southern counties that had high shares of slaves in 1860 are more likely to identify as a Republican, oppose affirmative action, and express racial resentment and colder feelings toward blacks. We show that these results cannot be explained by existing theories, including the theory of contemporary racial threat. To explain the results, we offer evidence for a new theory involving the historical persistence of political attitudes. Following the Civil War, Southern whites faced political and economic incentives to reinforce existing racist norms and institutions to maintain control over the newly freed African American population. This amplified local differences in racially conservative political attitudes, which in turn have been passed down locally across generations.

Must-Reads: May 21, 2016

- : Helicopter Money and Fiscal Policy

- : Remembrance of Bloggy Things Past

- : The Fed Ruins Summer: America’s Central Bank Picks a Poor Time to Get Hawkish

- Mark Thoma sends us to: **: Obama’s War on Inequality

- : EconoSpeak: Eduardo Porter on the Need For Fiscal Stimulus

- : Economics Has Failed America: “When it comes to the impact of global trade, the dismal science has done a dismal job explaining how to help workers hurt by globalization…”

- Weekend Reading: RIchard Hofstadter (1954): The Pseudo-Conservative Revolt

- Live from the Self-Made Gehenna That Is Twitter: Matt Bruenig is a very smart man…. Not on Twitter, Matt Bruenig is almost always very much worth reading…. On Twitter–that wretched hive of scum and villainy–not so much: Kevin Drum: The Great Matt Bruenig-Neera Tanden Kerfuffle Sort of Explained

Must-Read: Simon Wren-Lewis: Helicopter Money and Fiscal Policy

Must-Read: What I often hear: “Expansionary fiscal policy increases the burden of the national debt. That’s the reason expansionary fiscal policy is too risky. Helicopter money–social credit–is expansionary fiscal policy. But expansionary fiscal policy is too risky. Hence helicopter money is too risky.”

Stupid or evil? Simon Wren-Lewis does some intellectual garbage collection:

: Helicopter Money and Fiscal Policy: “John Kay and Joerg Bibow think additional government spending on public investment is a good idea…

…We can have endless debates about whether HM is more monetary or fiscal. While attempts to distinguish… can sometime clarify… ultimately… HM is what it is. Arguments that… use definitions to… conclude that central banks should not do HM because it’s fiscal are equally pointless. Any HM distribution mechanism needs to be set up in agreement with governments, and existing monetary policy has fiscal consequences which governments have no control over…..

At this moment in time… public investment should increase in the US, UK and Eurozone. There is absolutely no reason why that cannot be financed by issuing government debt…. HM does not stop the government doing what it wants with fiscal policy. Monetary policy adapts to whatever fiscal policy plans the government has, and it can do this because it can move faster than governments…. Kay… also suggests that HM is somehow a way of getting politicians to do fiscal stimulus by calling it something else. This seems to ignore why fiscal stimulus ended. In 2010 both Osborne and Merkel argued we had to reduce government borrowing immediately because the markets demanded it. HM… avoids the constraint that Osborne and Merkel said prevented further fiscal stimulus…. Many argue that these concerns about debt are manufactured… deficit deceit. HM, particularly in its democratic form, calls their bluff….

There is a related point in favour of HM that both Kay and Bibow miss. Independent central banks are a means of delegating macroeconomic stabilisation. Yet that delegation is crucially incomplete, because of the lower bound for nominal interest rates. While economists have generally understood that governments can in this situation come to the rescue, politicians either didn’t get the memo, or have proved that they are indeed not to be trusted with the task. HM is a much better instrument than Quantitative Easing, so why deny central banks the instrument they require to do the job they have been asked to do?

Weekend reading: “Production innovation” edition

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Central banks have long been in the business of buying bonds to fight economic downturns. But what if they bought stocks? This fairly radical idea is suggested by the economic research of Roger Farmer.

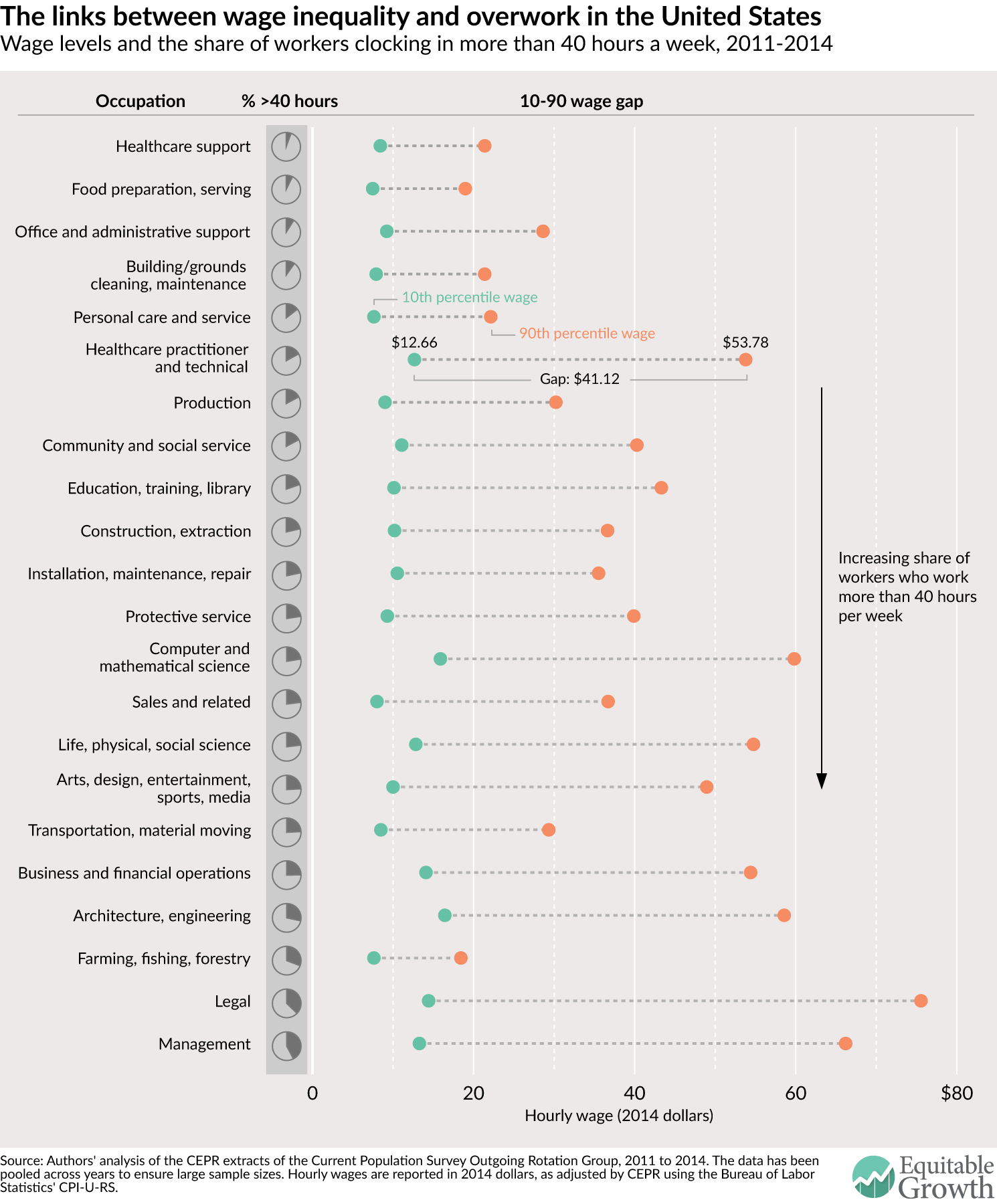

Long hours are sometimes seen as the sign of hard work and a job well done. But that’s not necessarily true. In a new report, Heather Boushey and Bridget Ansel look into the effects of long work hours on economic growth and inequality.

A new rule concerning equity crowdfunding was designed in the hope of boosting entrepreneurship and possibly letting someone besides institutional investors and the rich get access to the high-growth investments. The final rule announced this week seems unlikely to do either.

Speaking of final rules, the Department of Labor finalized its rule concerning overtime work, raising the threshold for eligible salaried workers to just over $47,000, significantly increasing the amount of workers covered. Bridget Ansel argues the new rule is good economics and good business.

As income has flowed more and more to the households at the top of the income ladder, it makes sense that companies would target where the money is going. A new working paper argues that the higher levels of income inequality has affected where product innovation is happening.

Links from around the web

One economic trend is like the weather: “everybody complains about productivity growth but nobody does anything about it.” Jared Bernstein asks a number of economists, included Equitable Growth’s Heather Boushey, about ideas to actually do something about productivity growth. [on the economy]

“GDP is a useful but limited measure. The problem is not with GDP, but with people who might see it as a comprehensive measure of well-being. It isn’t.” Dean Baker argues against including environmental or equity concerns in our common measure of economic output. [beat the press]

More and more attention is being paid to concerns about competition in the economy and the role of antitrust policy. Izabella Kaminska wonders if monopolism isn’t on the rise because all business strategies are now focused on claiming the monopolist throne for themselves. [ft alphaville]

The U.S. economy, at least measured in terms of the speed of output growth, may have had its best days in its past. Potential economic growth seems to be approaching outright stagnation and, as Eduardo Porter points out, policy needs to do something to help boost growth. [nyt]

Policymakers also have a problem in the short-term when it comes to economic growth. Members of the Federal Reserve’s policymaking committee have been giving signs they may raise interest rates again soon. Ryan Avent argues such a move would an incautious mistake. [free exchange]

Friday figure

Figure from “Overworked America” by Heather Boushey and Bridget Ansel

Must-read: Cardiff Garcia: Remembrance of Bloggy Things Past

Must-Read: : Remembrance of Bloggy Things Past:

Must-read: Ryan Avent: “The Fed Ruins Summer: America’s Central Bank Picks a Poor Time to Get Hawkish”

Must-Read: And agreement on my read of the Federal Reserve from the very sharp Ryan Avent. Nice to know that I am not crazy, or not that crazy…

: The Fed Ruins Summer: America’s Central Bank Picks a Poor Time to Get Hawkish: “THE… Federal Reserve… ha[s] been desperate to hike rates, often…

…keen to begin hiking in September, but were put off when market volatility threatened to undermine the American recovery. In December they managed to get the first increase on the books, and committee members were feeling cocky as 2016 began; Stanley Fischer, the vice-chairman, proclaimed that it would be a four-hike year… and here we are in mid-May with just the one, December rise behind us. But the Fed… is ready to give higher rates another chance…. Every Fed official to wander within range of a microphone warned that more rate hikes might be coming sooner than many people anticipate. And yesterday the Fed published minutes from its April meeting which were revealing:

Most participants judged that if incoming data were consistent with economic growth picking up…then it likely would be appropriate for the Committee to increase the target range for the federal funds rate in June….

[But] worries about runaway inflation are based on a view of the relationship between inflation and unemployment that looks shakier by the day…. Global labour and product markets are glutted… a global glut of investable savings too…. The Fed does not have cause to try to push inflation down. Its preferred measure of inflation continues to run below the Fed’s 2% target, as it has for the last four years. Somehow the Fed seems not to worry about what effect that might have on its credibility. All that undershooting has depressed market-based measures of inflation expectations…. If the Fed’s goal is to hit the 2% target in expectation, or on average, or most of the time, or every once in a while, or ever again, it might consider holding off on another rate rise until the magical 2% figure is reached. You know, just to make sure it can be done.

But the single biggest, overwhelming, really important reason not to rush this is the asymmetry of risks facing the central bank. Actually, the Fed’s economic staff explains this well; from the minutes:

The risks to the forecast for real GDP were seen as tilted to the downside, reflecting the staff’s assessment that neither monetary nor fiscal policy was well positioned to help the economy withstand substantial adverse shocks. In addition, while there had been recent improvements in global financial and economic conditions, downside risks to the forecast from developments abroad, though smaller, remained. Consistent with the downside risk to aggregate demand, the staff viewed the risks to its outlook for the unemployment rate as skewed to the upside.

The Fed has unlimited room to raise interest rates…. It has almost no room to reduce rates…. Hiking now is a leap off a cliff in a fog; one could always wait and jump later once conditions are clearer, but having jumped blindly one cannot reverse course if the expected ledge isn’t where one thought it would be…