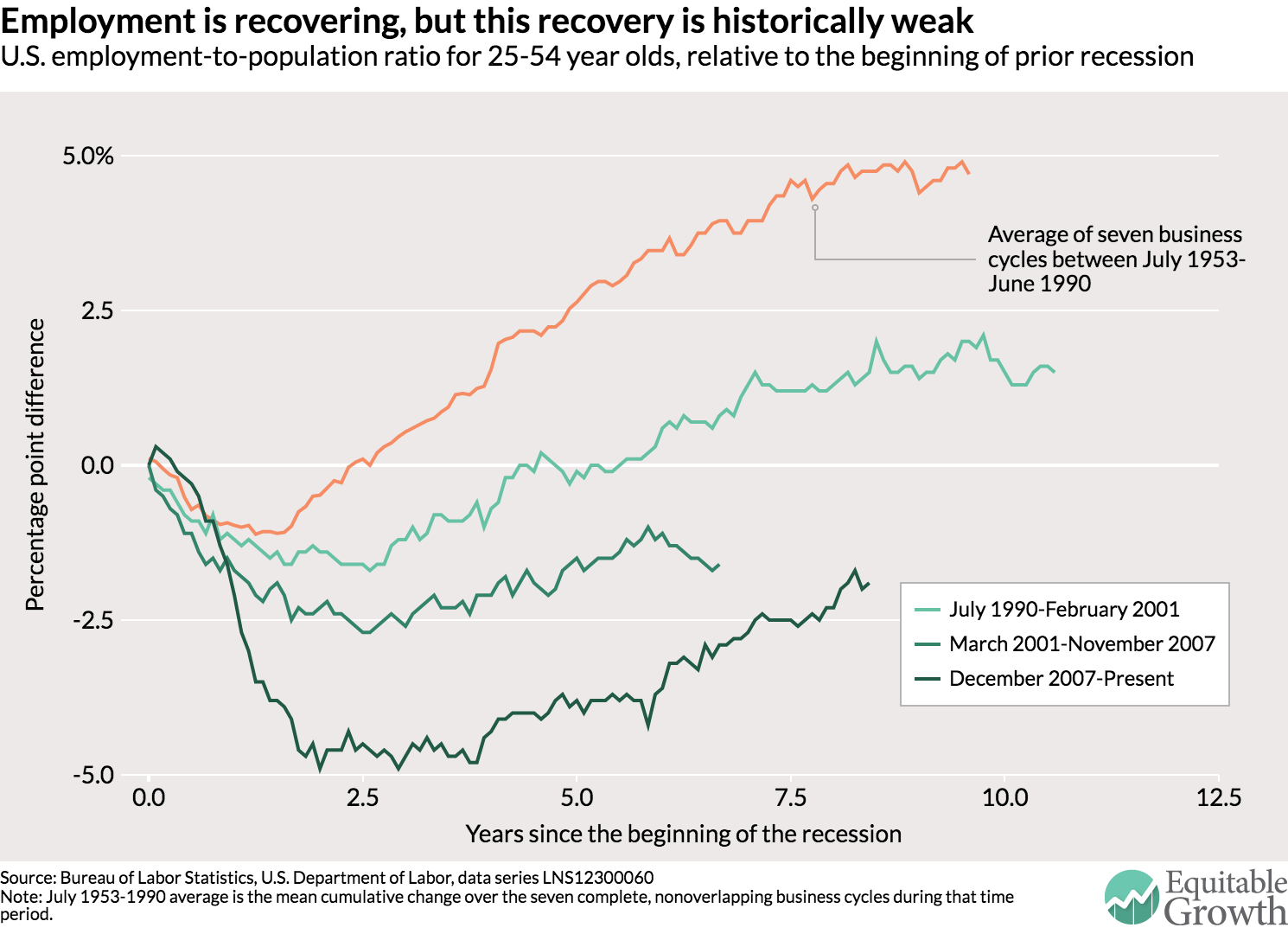

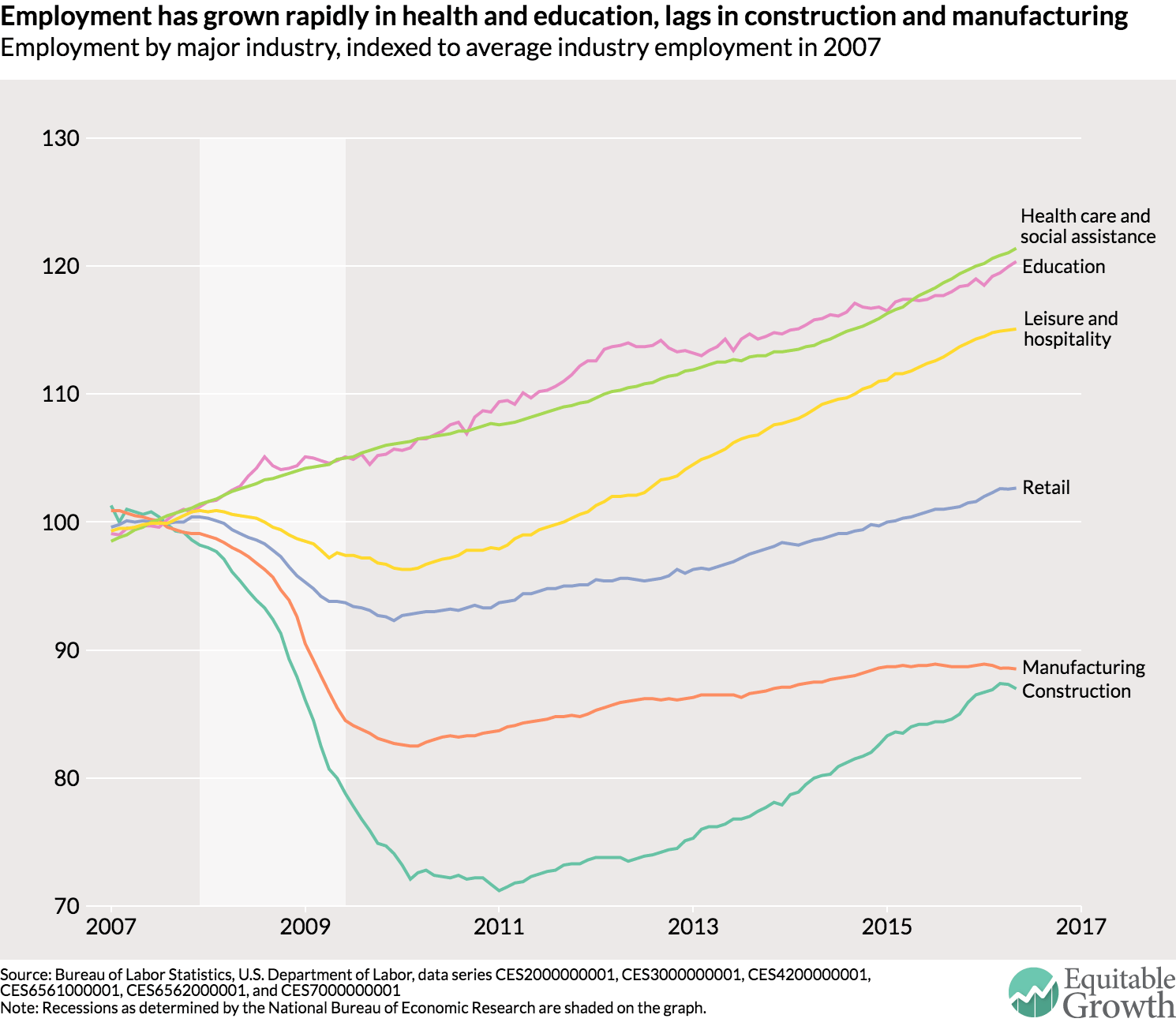

“We have lost 5 percent of capacity… $800 billion[/year]…. A soft economy casts a substantial shadow forward onto the economy’s future output and potential.” It is now three years later than when Summers and the rest of us did these calculations. If you believe Janet Yellen and Stan Fischer’s claims that we are now effectively at full employment, the permanent loss of productive capacity as a result of the 2007-9 financial crisis, the resulting Lesser Depression, and the subsequent bobbling of the recovery is not 5% now. It is much closer to 10%. And it is quite possibly aiming for 15% before it is over:

Lawrence Summers et al. (2014): Lack of Demand Creates Lack of Supply: “Jean-Baptiste Say, the patron saint of Chicago economists…

…enunciated the doctrine in the 19th century that supply creates its own demand…. If you produce things… you would have to create income… and then the people who got the income would spend the income and so how could you really have a problem[?]… Keynes… explain[ed] that [Say’s Law] was wrong, that in a world where the demand could be for money and for financial assets, there could be a systematic shortfall in demand.

Here’s Inverse Say’s Law: Lack of demand creates, over time, lack of supply…. We are now in the United States in round numbers 10 percent below what we thought the economy’s capacity would be today in 2007. Of that 10 percent, we regard approximately half as being a continuing shortfall relative to the economy’s potential and we regard half as being lost potential…. We have lost 5 percent of capacity… we otherwise would have had…. $800 billion[/year]. It is more than $2,500[/year] for every American…. A soft economy casts a substantial shadow forward onto the economy’s future output and potential. This might have been a theoretical notion some years ago, it is an empirical fact today…

What are we going to do?

Well, we are going to do nothing–or, rather, next to nothing. Life would be convenient for the Federal Reserve if right now (a) the U.S. economy were at full employment, (b) a rapid normalization of interest rates were necessary to avoid inflation rising significantly above the Federal Reserve’s 2%/year PCE chain index inflation target, and (c) U.S. tightening were more likely to stimulate economies abroad via greater opportunities to sell to the U.S. than contract economies abroad by withdrawing risk-bearing capacity. And the Federal Reserve appears to have decided to believe what makes life convenient. Thus nothing additional in the way of action to boost the economy can be expected from monetary policy. And on fiscal policy a dominant or at least a blocking position is held by those who, as the very sharp Olivier Blanchard put it recently, even though:

[1] In the short run, the demand for goods determines the level of output. A desire by people to save more leads to a decrease in demand and, in turn, a decrease in output. Except in exceptional circumstances, the same is true of fiscal consolidation [by governments]…

nevertheless Olivier Blanchard:

was struck by how many times… [he] had to explain the “paradox of saving” and fight the Hoover-German line, [2] “Reduce your budget deficit, keep your house in order, and don’t worry, the economy will be in good shape”…

Apparently he was flabbergasted by the number of people who would agree with [1] in theory and yet also demand that policies be made according to [2], and he plaintively asks for:

anybody who argues along these lines must explain how it is consistent with the IS relation…

Remember: the United States is not that different. As Barry Eichengreen wrote:

It is disturbing to see the refusal of [fiscal] policymakers, particularly in the US and Germany, to even contemplate… action, despite available fiscal space (as record-low treasury-bond yields and virtually every other economic indicator show). In Germany, ideological aversion to budget deficits runs deep… rooted in the post-World War II doctrine of “ordoliberalism”…. Ultimately, hostility to the use of fiscal policy, as with many things German, can be traced to the 1920s, when budget deficits led to hyperinflation. The circumstances today may be entirely different from those in the 1920s, but there is still guilt by association, as every German schoolboy and girl learns at an early age.

The US[‘s]… citizens have been suspicious of federal government power, including the power to run deficits…. From independence through the Civil War, that suspicion was strongest in the American South, where it was rooted in the fear that the federal government might abolish slavery. In the mid-twentieth century… Democratic President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s “Great Society”… threatened to withhold federal funding for health, education, and other state and local programs from jurisdictions that resisted legislative and judicial desegregation orders. The result was to render the South a solid Republican bloc and leave its leaders antagonistic to all exercise of federal power… a hostility that notably included countercyclical macroeconomic policy. Welcome to ordoliberalism, Dixie-style. Wolfgang Schäuble, meet Ted Cruz…

The world very badly needs an article–a long article, 20,000 words or so. It would teach us how we got into this mess, why we failed to get out, and how the situation might still be rectified–so that the Longer Depression of the early 21st century does not dwarf the Great Depression of the 20th century in future historians’ annals of macroeconomic disasters. Such a book would have to assimilate and transmit the lessons of what I think of as the six greatest books on our current ongoing disaster:

Plus it would have to summarize and evaluate Larry Summers’s musings on secular stagnation.

We were lucky that John Maynard Keynes started writing his General Theory summarizing the lessons we needed to learn from the Great Depression even before that depression reached its nadir. But we were not lucky enough. As Eichengreen stresses, only half the lessons of Keynes were assimilated–enough to keep us from repeating the disaster, but not enough to enable us to get out of it. (Although, to be fair, the world of the 1940s emerged from it only at the cost of imbibing the even more poisonous and deadly elixir called World War II.)

Paul? (Krugman, that is.) Are you up to the task?