This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Why have students of for-profit colleges, who tend to have less debt that traditional students, seen their student loan default rates rise so much? Perhaps because the average for-profit student sees their earnings decline after attendance.

The relatively weak growth in business investment since the Great Recession has some economists puzzled. Maybe low interest rates have contributed to investment’s slow growth due to retirees’ investment decision-making? Given the assumptions about retirees this hypothesis requires, it seems unlikely.

Equitable Growth published our batch of working papers for June. This month’s papers include research on the effect of credit on job finding and output, a review of a new text book on immigration economics, and a paper trying to understand why a negative employment effect of the minimum wage is so hard to find.

Ben Zipperer writes about the new paper on the employment effects of the minimum wage, detailing the possible reasons why this negative effect hasn’t shown up in empirical work. The possibilities range from the effects on consumer demand to the idea that the perfectly competitive model of the labor market could be wrong.

Debates about the corporate income tax in the United States usually focus just on the marginal tax rate. While the rate is very important (it determines how much of an additional dollar is taxed), we can’t forget the importance of the tax base (how much of income is actually taxed).

Rents, you have heard, are too high in many coastal U.S. cities. Yet the trend may get worse over the next decade if trends continue. Nisha Chikhale points out important trends for rental demand and offers some possible policy solutions.

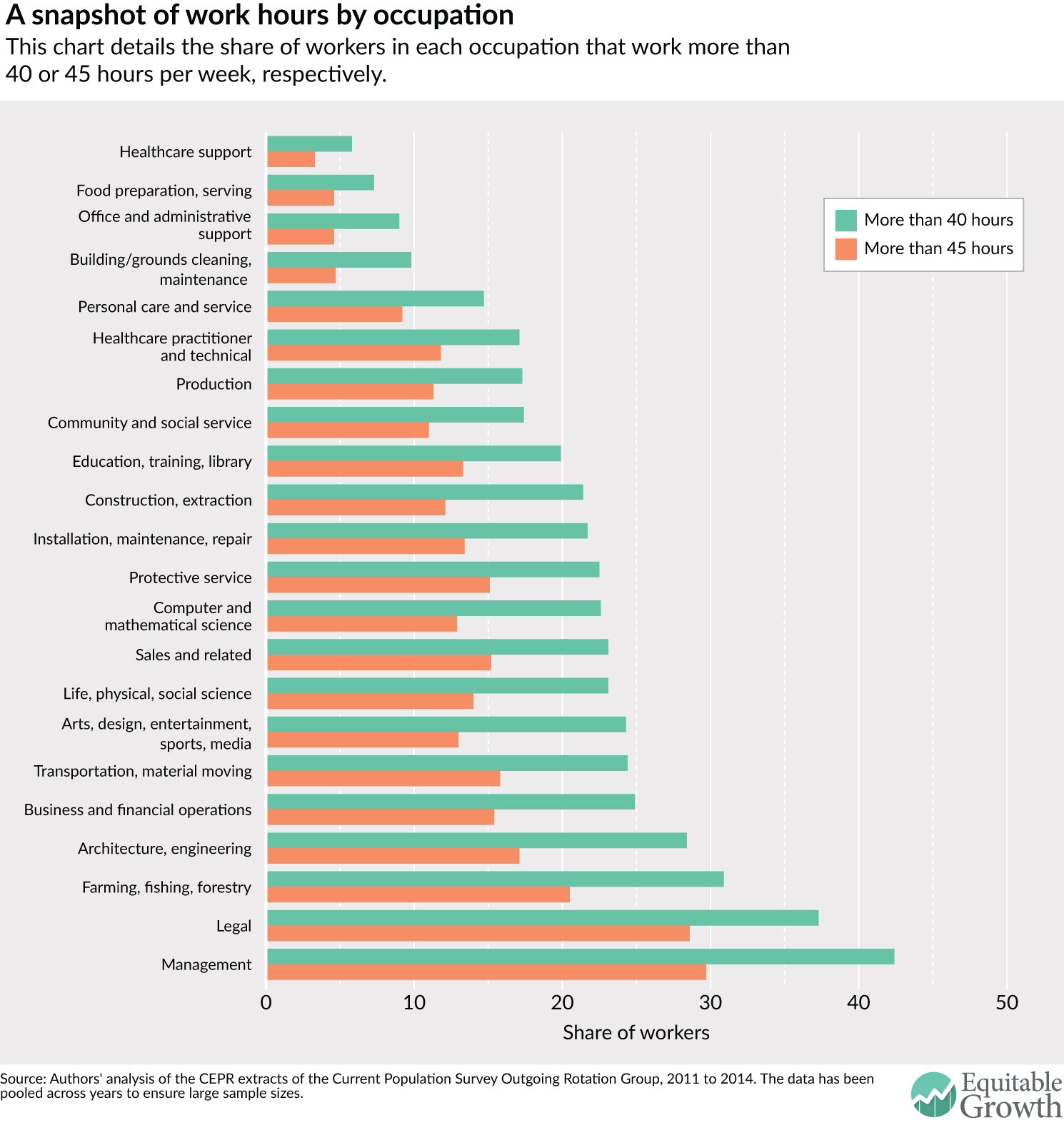

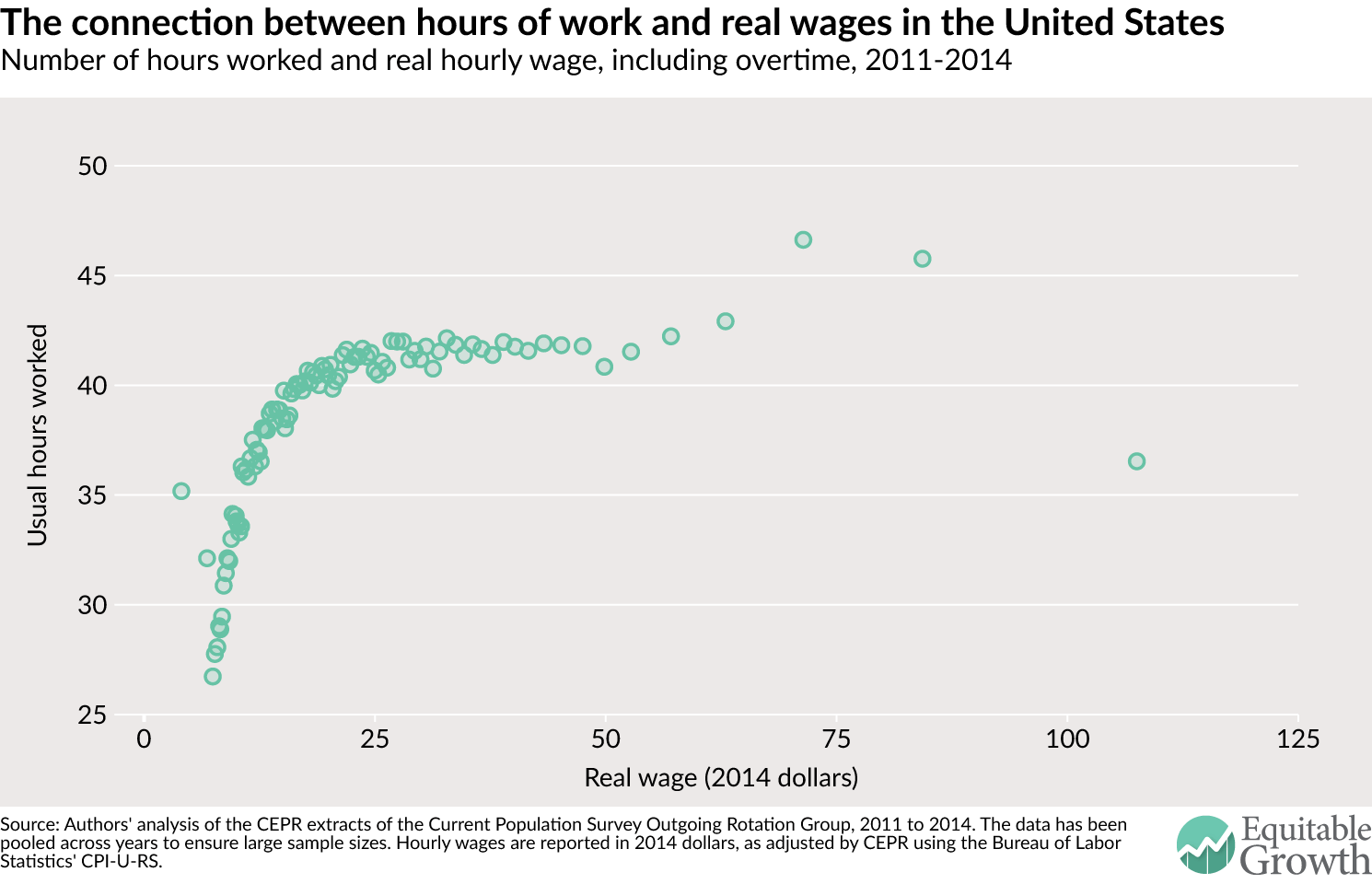

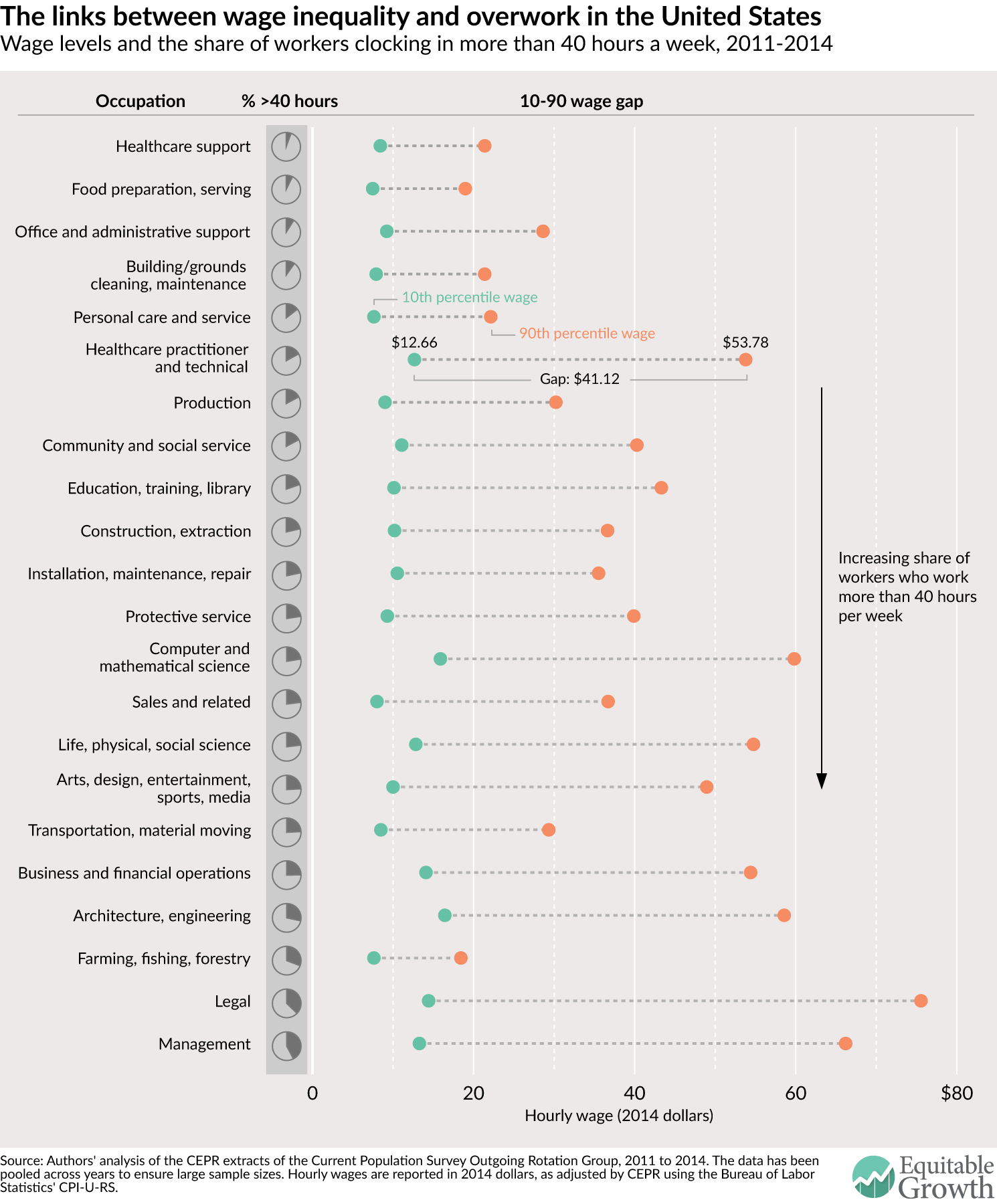

With the U.S. Department of Labor finalizing its new rule on overtime regulations, reminding ourselves of the state of overwork in the United States seems like a worthwhile endeavor. Heather Boushey and Bridget Ansel highlight three key charts from their recent report.

Links from around the web

One of the many open questions about the Federal Reserve’s unconventional monetary policies to rebound from the Great Recession is how much it affected inequality. As the responses to this IGM Forum question from a panel of economists show, we really don’t know the answer. [igm]

Negative nominal interest rates used to be unthinkable. But now moderately negative interest rates are part of central banks’ policy toolbox. Narayana Kocherlakota discusses how communications policy will be a key part of using negative rates in the future. [bloomberg view]

Public education in the United States is very segregated by race. The implications of this segregation and the resulting inequality in access to education are huge. Nikole Hannah-Jones details the segregation in New York’s public schools and efforts to change it. [nyt magazine]

In 2011, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen argued that software was “eating the world.” Five years later, Conor Sen argues that housing, after a post-crisis lull, is about to eat the U.S. economy. [csen]

Speaking of housing, Josh Lehner proposes a “housing trilemma” for U.S. cities. A city may want to have a strong economy, a high quality of life, and housing affordability. But seemingly they can only get two of those three options at once. [oregon economic analysis]

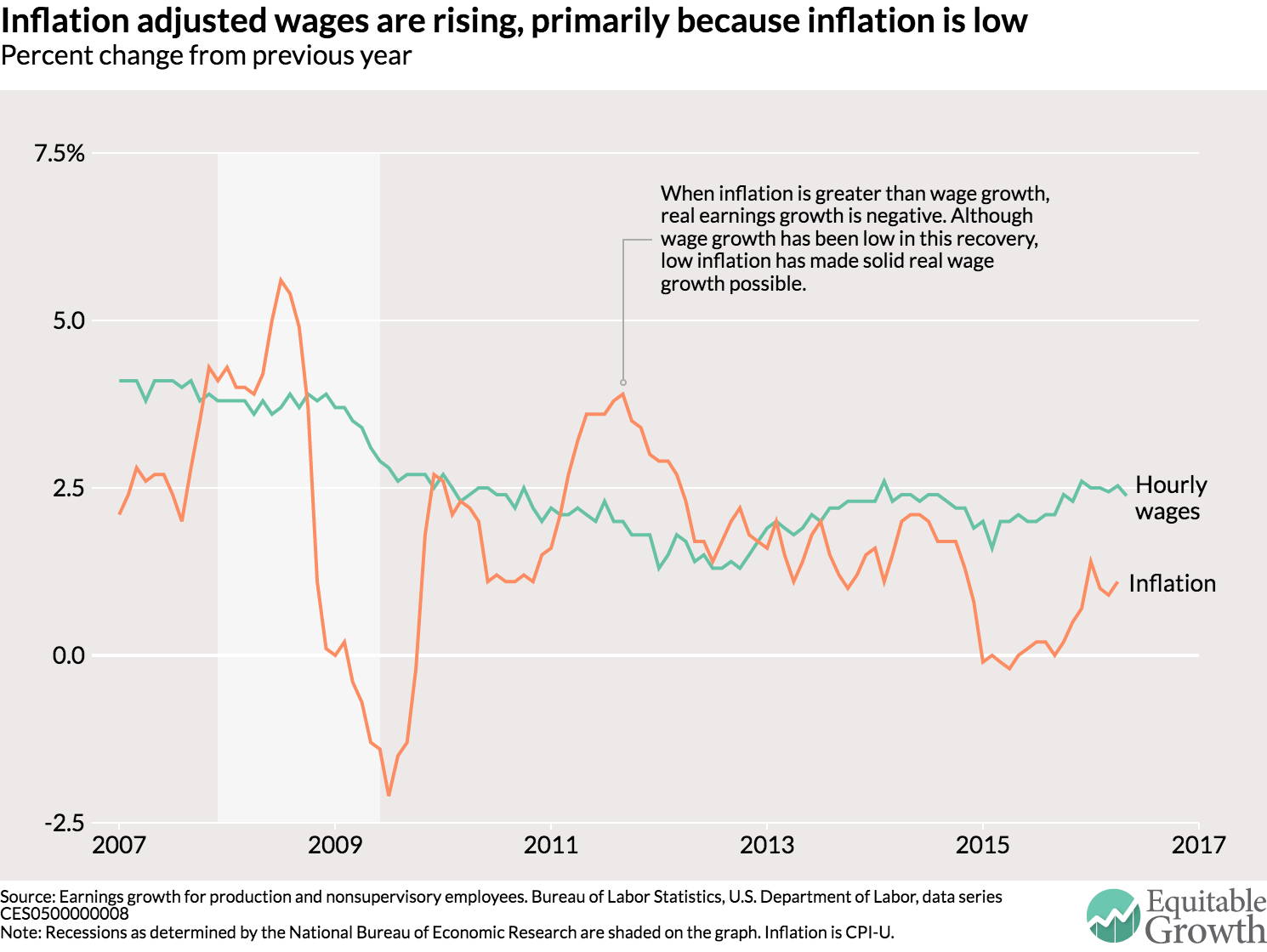

Friday figure

Figure from “Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: May 2016 Report Edition”