The very sharp Ken Rogoff predicts a boom over the next four years: “The biggest missing piece… is business investment, and if it starts kicking in… output and productivity could begin to rise very sharply…. You don’t have to be a nice guy to get the economy going…. It is far more likely that after years of slow recovery, the US economy might at last be ready to move significantly faster…”

I really can’t see it as likely. Rogoff talks about:

- “the prospect of a massive stimulus, featuring a huge expansion of badly needed infrastructure spending…” but Trump’s stimulus proposal as of now is for tax subsidies to projects that would be built in any event coupled with privatization to restrict use. There is definitely space for fiscal stimulus and infrastructure–and we should lobby and argue hard to use that space–but what appears to be on Trump’s agenda is a bunga-bunga Berlusconi-like policy.

-

“a massive across-the-board income-tax cut that disproportionately benefits the rich… [although it] hardly seems as effective as giving cash to poor people… tax cuts can be very good for business confidence…” but I haven’t seen cases in which this is true–rather, rich people say that tax cuts are very good for business confidence and then skip town with the money.

-

“repealing Obama-era regulation… businesses will be ecstatic, maybe enough to start really investing again. The boost to confidence is already palpable…” but I can’t see a bigger carbon-energy boom than we have had, I don’t notice other labor or environmental regulations binding–certainly not in the Seattle restaurant industry–and, this morning, Boeing is really not ecstatic about a president Trump.

-

“the huge shadow Obamacare casts on the health-care system, which alone accounts for 17% of the economy…” but ObamaCare is primarily a source of money for health care, not a regulatory drain. Repeal of ObamaCare would be–as every hospital and insurance company is right now telling everyone on Capitol Hill who will listen–a major downer. Who is Rogoff talking to? When he made this point earlier, he referred to the “substantial regulatory burden of ObamaCare on small business”. But there never was any. Small businesses–those with less than fifty employees–face no burden. Those few larger businesses–those with fifty employees or more–that do not offer employer-sponsored health insurance face a not-yet-implemented and often-postponed 2% of payroll tax. That’s a cost to them, but a benefit to their many, many competitors who have been offering employer-sponsored insurance.

And:

- “Even steadfast opponents of President-elect Trump’s economic policies would have to admit they are staunchly pro-business (with the notable exception of trade)…” Enough said.

By saying that a boom is “far more likely” than the opposite, I think Rogoff is playing a 20% chance as if it were a 60% chance. And I do not understand what makes him see the world this way. Tax credits for already-planned infrastructure projects are not fiscal stimulus, ObamaCare is not a substantial regulatory burden on small business, etc. Or do I not live in the real world?

Kenneth Rogoff: The Trump Boom?: “Under President Barack Obama, labor regulation expanded significantly…

…not to mention the dramatic increase in environmental legislation. And that is not even counting the huge shadow Obamacare casts on the health-care system, which alone accounts for 17% of the economy. I am certainly not saying that repealing Obama-era regulation will improve the average American’s wellbeing. Far from it. But businesses will be ecstatic, maybe enough to start really investing again. The boost to confidence is already palpable.

Then there is the prospect of a massive stimulus, featuring a huge expansion of badly needed infrastructure spending. (Trump will presumably bulldoze Congressional opposition to higher deficits.) Ever since the 2008 financial crisis, economists across the political spectrum have argued for taking advantage of ultra-low interest rates to finance productive infrastructure investment, even at the cost of higher debt. High-return projects pay for themselves.

Far more controversial is Trump’s plan for a massive across-the-board income-tax cut that disproportionately benefits the rich. True, putting cash in the pockets of rich savers hardly seems as effective as giving cash to poor people who live hand to mouth. Trump’s opponent, Hillary Clinton, memorably spoke of “Trumped-up trickle-down economics.” But, Trumped-up or not, tax cuts can be very good for business confidence.

It is hard to know just how much extra debt Trump’s stimulus program will add, but estimates of $5 trillion over ten years – a 25% increase – seem sober. Many left-wing economics commentators, having insisted for eight years under Obama that there is never any risk to US borrowing, now warn that greater borrowing by the Trump administration will pave the road to financial Armageddon. Their hypocrisy is breathtaking, even if they are now closer to being right.

Exactly how much Trump’s policies will raise output and inflation is hard to know. The closer the US economy is to full capacity, the more inflation there will be. If US productivity really has collapsed as much as many scholars believe, additional stimulus is likely to raise prices a lot more than output; demand will not induce new supply.

On the other hand, if the US economy really does have massive quantities of underutilized and unemployed resources, the effect of Trump’s policies on growth could be considerable. In Keynesian jargon, there is still a large multiplier on fiscal policy. It is easy to forget the biggest missing piece of the global recovery is business investment, and if it starts kicking in finally, both output and productivity could begin to rise very sharply.

Those who are deeply wedded to the idea of “secular stagnation” would say high growth under Trump is well-nigh impossible. But if one believes, as I do, that the slow growth of the last eight years was mainly due to the overhang of debt and fear from the 2008 crisis, then it is not so hard to believe that normalization could be much closer than we realize. After all, so far virtually every financial crisis has eventually come to an end….

At the risk of hyperbole, it’s wise to remember that you don’t have to be a nice guy to get the economy going. In many ways, Germany was as successful as America at using stimulus to lift the economy out of the Great Depression.

Yes, it still could all end very badly. The world is a risky place. If global growth collapses, US growth could suffer severely. Still, it is far more likely that after years of slow recovery, the US economy might at last be ready to move significantly faster, at least for a while.

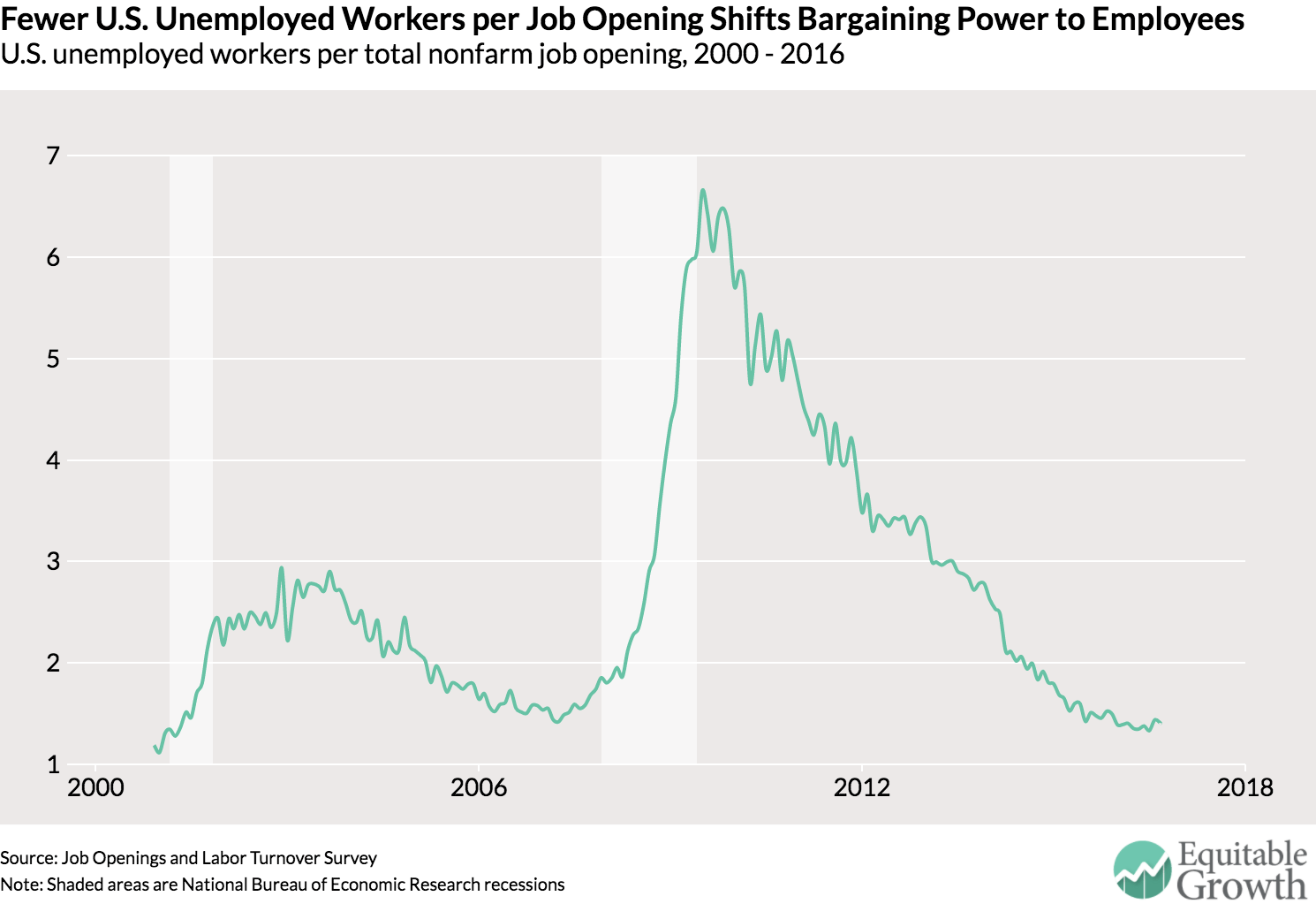

A third and final metric from the JOLTS data is the number of unemployed workers per job opening. A slack or weak labor market will have a high ratio of workers who are laid off and employers who aren’t looking to hire. A higher ratio means employers have relatively more implicit bargaining power as there are more workers competing for a set number of job openings. Workers’ ability to bargain over pay or working conditions starts moving back to workers as the ratio declines. Of course, with so few workers having a union to support them in any negotiations, the ability to bargain with an employer (or potential employer) is based on the individual’s capacity. The current ratio is now at levels slightly lower than pre-recession levels. (See Figure 3.)

A third and final metric from the JOLTS data is the number of unemployed workers per job opening. A slack or weak labor market will have a high ratio of workers who are laid off and employers who aren’t looking to hire. A higher ratio means employers have relatively more implicit bargaining power as there are more workers competing for a set number of job openings. Workers’ ability to bargain over pay or working conditions starts moving back to workers as the ratio declines. Of course, with so few workers having a union to support them in any negotiations, the ability to bargain with an employer (or potential employer) is based on the individual’s capacity. The current ratio is now at levels slightly lower than pre-recession levels. (See Figure 3.) This metric also shows that the labor market is back at prerecession levels, but notice again that it was much lower in 2000 (a bit over 1) when the labor market has generally regarded at full employment. This ratio might be a good indicator of full employment—if by it we mean a situation where workers can easily find a job and have strong bargaining power. In his book “Full Employment in a Free Society,” the late British economist Sir William Beveridge

This metric also shows that the labor market is back at prerecession levels, but notice again that it was much lower in 2000 (a bit over 1) when the labor market has generally regarded at full employment. This ratio might be a good indicator of full employment—if by it we mean a situation where workers can easily find a job and have strong bargaining power. In his book “Full Employment in a Free Society,” the late British economist Sir William Beveridge