Business owners often use their firms as tax shelters, reducing government revenue and reported income inequality

Picture this scene: After sharing a meal with friends, someone in the group grabs the check and says, “I’ll take this so I can expense it through my company.” It seems like a win-win. The business owner “writes off” the expense to save on the firm’s taxes, and the rest of the group gets a free meal.

Yet this isn’t a victimless crime. In fact, according to my recent study using detailed data from Portugal, personal consumption disguised as tax-deductible business expenses carries a loss in government revenues equivalent to at least 1 percent of Gross Domestic Product. To put that in perspective, this tax gap (the difference between taxes owed and taxes paid) is larger than the estimated losses from individual cross-border tax evasion, which range from 0.22 to 0.62 percent of GDP for Portugal (and are not above 1 percent for any European country).

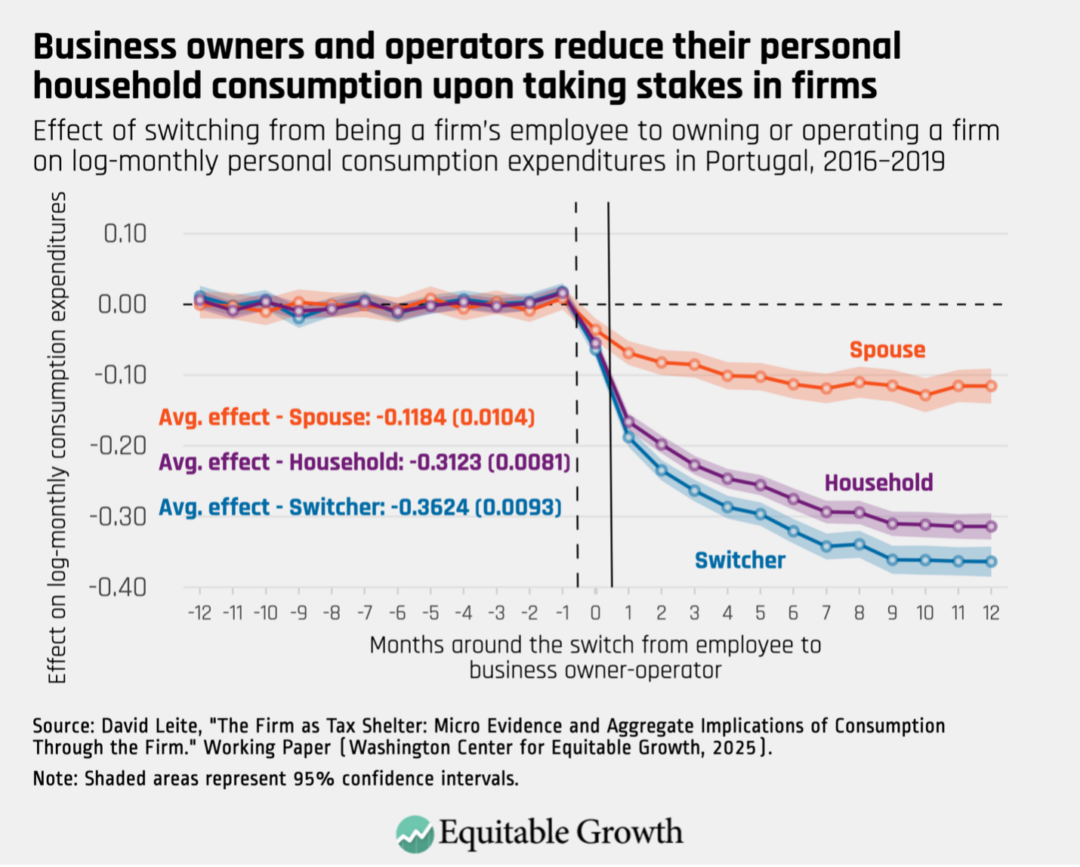

The study, released today in Equitable Growth’s Working Paper series, focuses on the personal consumption expenditures of individuals who move from being employees of firms to owning or operating those firms or their own businesses. I find that people who become high-level business managers or entrepreneurs report up to a 36 percent drop in personal consumption in the months following the switch. I also find that the consumption of the spouses of these owners and operators also falls by 12 percent, despite their sources of income not changing. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

What drives the drop in business owners’ consumption?

This drop in consumption could be due to a number of things. It might be that entrepreneurs have significantly lower income than salaried employees. Or perhaps the investment needed to start their businesses lead to a permanent reduction in consumption. But another hypothesis is that part of their personal consumption is now being recorded as business expenses.

To distinguish between these explanations, I check whether the effect is driven by a drop in income that coincides with the transition to business owner or manager. The data show that reported income for new entrepreneurs falls by 3.7 percent in the first year but then recovers. This change seems too small to explain a drop of more than 30 percent in reported personal consumption.

Next, I determine what kinds of expenses new business owners cut back on to see if that helps explain the drop in consumption. I find substantial drops in reported spending at supermarkets and car repair garages—a nearly 50 percent reduction. Reported spending at hotels and restaurants also falls by about 30 percent, as does spending on professional services, such as lawyers and accountants, and communication technologies including internet and mobile-phone services.

In all of these categories, I also find a decline, albeit smaller, in reported spending by the spouses of business owners. Importantly, these expense categories fall into the gray area between personal consumption and what could plausibly be considered legitimate business expenses for tax purposes.

It therefore could be that new business owners are simply tightening their belts to spend less and put all their savings into their new business. If that were the case, then we should see a similar reduction in spending across other categories that are harder to justify as business expenses, including nonessential health care, private education, or basic utilities, such as water, electricity, and gas. Yet the data do not show such a drop in this spending around the time individuals switch from being employees to owning or managing their businesses.

As such, it is likely that these business owners are not reducing their actual consumption at all, but instead are consuming through their firms when they can get away with it.

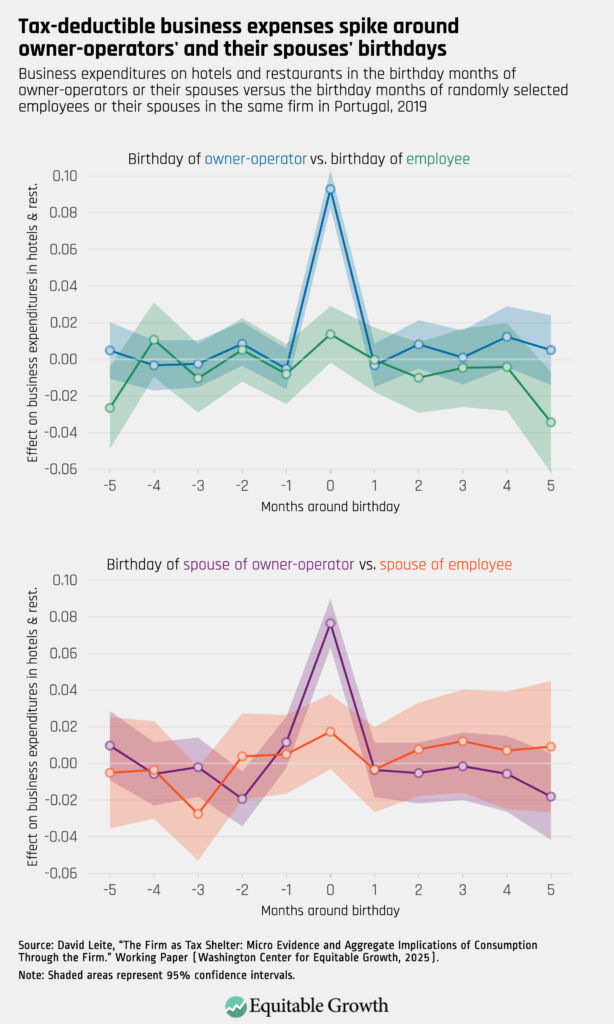

Perhaps the most compelling evidence of this is how company spending on hotels and restaurants changes during the month of the business owner’s birthday, compared to the birthday month of a randomly selected employee. The results are striking: Spending on hotels and restaurants is 10 percent higher in the month of the business owner’s birthday, while there is no change at all during the birthday months of other employees at the same company. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

It seems likely, then, that business owners are mischaracterizing birthday celebration expenditures—clearly a personal expense—as a tax-deductible business expense.

Implications for tax revenue and income inequality

In Portugal, when business owners report personal expenses as business expenses, they are simultaneously evading multiple taxes. They avoid paying personal income tax on the distribution of business income, inflate business costs to reduce reported profits, and lower the company’s tax liability. They also evade the Value Added Tax—akin to a sales tax on all personal consumption of goods and services within the country, ranging from 6 percent to 23 percent—by claiming business expenses as a tax credit to offset the VAT charged by the company on its sales.

The percentage of tax savings from this evasion depends on the tax rates. Specifically, I estimate that the tax savings amount to about 45 percent under the Portuguese tax system. For every euro of personal consumption reported as a business expense, the owners would have to pay themselves 1.80 euros in salary to achieve the same level of consumption while complying with the law.

The general perception has been that this behavior, although common, likely has little impact on public finances at the aggregate level. Yet my paper shows that the fiscal cost can be quite significant. I estimate that it results in a revenue loss of at least 1 percent of Portugal’s GDP.

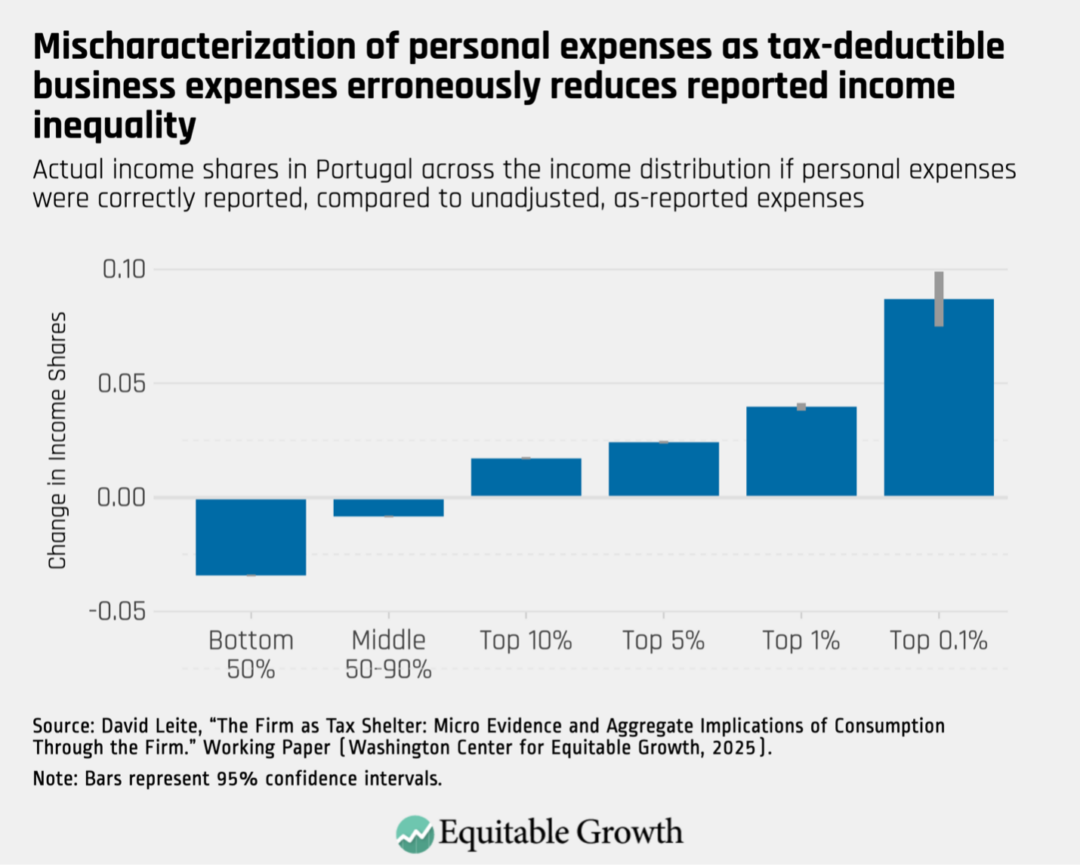

Furthermore, my analysis demonstrates that this behavior is not limited to the low- and middle-income owners of mom-and-pop stores, but is prevalent among owners and operators of highly profitable businesses at the top of the income distribution, too. I estimate that if this behavior were detected and personal expenses correctly reported, income inequality in Portugal (as measured by the Gini coefficient) would increase by 1 percentage point, while the income share of the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution would increase by nearly 10 percent. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Implications for U.S. tax policy

The detailed, individual-level consumption data my study uses comes from a VAT compliance policy introduced in Portugal in 2013. Though the United States does not have a comparable policy in place, I believe the findings would hold if a similar hypothesis were tested here.

Like Portugal, the United States has a large number of closely held businesses, sometimes called pass-through firms because of the way these firms’ tax liability is “passed through” to owners’ personal income tax returns. As in Portugal (and other countries), the owners of these U.S. firms have a strong tax incentive to use the firm to pay for personal expenses, and, in fact, the standard for tax-deductible expenses in the United States—what the Internal Revenue Code describes as “ordinary and necessary”—is both broad and ill-defined, opening the door to either intentional or unintentional mischaracterization.

There are some bright-line limits, though. Since business meals are known to be borderline cases, for example, the IRS allows a $0.50 deduction for every $1 spent. Additionally, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act repealed the business entertainment deduction, which had previously allowed a tax deduction for the expense of entertaining business associates at bars, country clubs, and sporting events, among other locales. Yet the 2017 bill moved in the other direction on the depreciation deduction for use of a passenger-vehicle for business, significantly increasing the cap on this notoriously hard-to-enforce deduction.

Business owners are supposed to keep records to substantiate any deductions claimed, but there is very little third-party reporting and audit rates are low. As such, many experts suspect that mischaracterization of pass-through business expenses substantially contributes to the U.S. tax gap. The nonpartisan congressional investigative arm of the U.S. Congress, the Government Accountability Office, finds that 76 percent of sole proprietors—those who own and operate their own businesses, which are treated as pass-throughs in the United States—misreported their total business expenses to the tune of $92 billion on average per year between 2013 and 2015. The most likely expenses to be misreported were car and truck expenses, utilities, travel, and business use of home.

If true, and if, as in Portugal, mischaracterization is more prevalent among high-income U.S. business owners, then already-high measures of U.S. inequality are likely to have been significantly understated—and thus the link between inequality and the problems partially caused by it (namely democratic erosion and slow economic growth) likely are also understated.

Overall, my study indicates that policymakers in Portugal and across the globe should be redoubling efforts to better define and enforce the tax laws that govern appropriate deducting of business expenses.

—David Leite is an applied economist focusing on public finance. He recently completed his Ph.D. in economics at the Paris School of Economics and will start a postdoctoral fellowship at the National Bureau of Economic Research in September 2025.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!