Antitrust experts call on Congress to address failings in antitrust law to preserve competition and prevent monopolies in digital marketplaces

Overview

A group of the nation’s top U.S. antitrust experts told Congress this week that outdated and bad economic theory has undermined antitrust enforcement, allowing dominant companies to gain an unfair advantage in the marketplace to the detriment of other businesses and consumers, innovation, and productivity growth. These prominent experts called on Congress to revise current law to align it with modern economic theory and to fix harmful judicial rules: “The signatories to this letter agree that antitrust enforcement has become too lax, in large part because of the courts, and that Congress must act to correct the state of antitrust enforcement.”

The statement, a “Joint Response to the House Judiciary Committee on the State of Antitrust Law and Implications for Protecting Competition in Digital Markets,” should serve as a wake-up call to Congress, the courts, enforcers, and antitrust practitioners. The signees of the statement calling for dramatic reform—see the list of individual names and their affiliations at the end of this column—include some of the most respected industrial organization (the field that studies competition and markets) economists and experienced antitrust practitioners, all of whom have spent a majority of their careers studying these issues either in academia or practicing antitrust law. Many have served as top enforcers at the Federal Trade Commission or the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, the two federal agencies primarily responsible for antitrust review and enforcement.

The statement responds to a request from the House Judiciary Committee for views on the state of federal antitrust law as part of the committee’s investigation into competition in digital markets. The conclusions are blunt, and the prognosis, absent change, is bleak. “Economic research establishes that market power is now a serious problem,” according to the statement, and “current antitrust doctrines are too limited to protect competition adequately—making it needlessly difficult to stop anticompetitive conduct in digital markets.”

Nor should their conclusion be controversial: “We believe that any conclusion to the contrary reflects either an incomplete or incorrect understanding of economics and the economic literature from the past several decades.” The statement closes with a set of recommendations:

- Nullify existing precedent that limits antitrust actions

- Clarify that the antitrust laws protect potential competition

- Establish legal rules that, in appropriate cases, require defendants to prove their conduct does not harm competition

- Increase penalties and enforcement resources

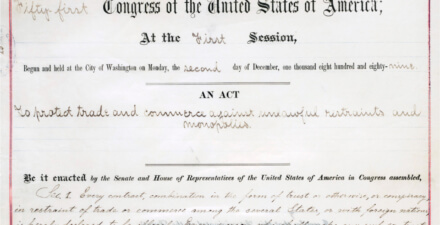

This column briefly details the statement and its recommendations. But their overarching conclusion is that current antitrust law is not protecting competition, and Congress, as it did in 1914 and 1950, must pass legislation to fix it.

The House Judiciary Committee investigation into competition in digital markets

The House Judiciary Committee began its investigation into competition in digital markets in June 2019. Digital markets cover a broad range of online services. They include social networking, online advertising, and online marketplaces for goods and services. Unsurprisingly, the investigation has focused on four companies: Amazon.com Inc., Apple, Inc., Facebook, Inc., and Alphabet Inc.’s Google unit. The committee’s goals are: “documenting problems in digital markets, examining whether dominant firms are engaging in anti-competitive conduct, and assessing whether existing antitrust laws, competition policies, and current enforcement levels are adequate to address these issues.”

Over the course of the past 10 months, the House Judiciary Committee held a number of hearings focusing on dynamics of these digital markets. The committee members listened to market participants who believe competition has been stifled, other market participants who believe these markets are functioning well, and a variety of experts. (Also testifying before the committee were Washington Center for Equitable Growth Steering Committee Member Jason Furman, professor of the practice of economic policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, and Fiona Scott Morton, professor of economics at Yale School of Management and an Equitable Growth grantee).

The statement addresses how successful antitrust laws would be in prohibiting harmful conduct in digital markets, if such conduct is occurring or does occur. The focus may seem odd. Antitrust laws are supposed to prevent anticompetitive conduct. So, how could it be that anticompetitive conduct is legal? Well, because U.S. antitrust laws themselves are broad and general, what is legal is left to the courts to define key terms and provisions. The statement to the committee examines whether the interpretation and application of antitrust laws by the courts and federal antitrust enforcers prevents or stops anticompetitive conduct, without unnecessarily condemning procompetitive actions.

Problems with current antitrust law

This group’s consensus view, based on the best economic theory and research, is that courts have been too willing to limit the scope of the antitrust laws and allow conduct that undermines competition. Monopoly power is growing in the United States, a conclusion supported by a broad range of evidence. Multiple studies find market power rising in industries such as hospitals, brewing, and airlines. Equitable Growth’s comprehensive literature review, authored by Yale’s Scott Morton, provides additional evidence, including how internet platforms can use (and some have used) restrictions on pricing (known as Most Favored Nation clauses) to suppress competition and harm competition.

Antitrust rules developed by courts have contributed to this problem. As the statement explains, “Antitrust has failed to respond to growing market power in substantial part because many key antitrust precedents—particularly those precedents governing exclusionary conduct—rely on unsound economic theories or unsupported empirical claims about the competitive effects of certain practices.”

Here’s just one case in point: In the 1980s, the federal government successfully challenged and broke-up AT&T’s phone monopoly, which helped spur the telecommunications revolution that led to competition for phone services, cell phones, and then smart phones. Under today’s legal standards, it is questionable whether the government could have won that case.

The implications of weakened antitrust law for digital markets

These judicial interpretations of federal antitrust laws over the past several decades make it unnecessarily difficult to successfully challenge anticompetitive conduct and acquisitions in digital markets. As the statement points out, “While these troubling judicial rules and decisions impede effective antitrust enforcement generally, they do so particularly with respect to protecting competition in the digital marketplace.”

The legal rules most weakened by courts apply to the types of anticompetitive conduct that has sparked the House Judiciary Committee’s concerns about digital markets, which Equitable Growth has discussed here, here, and here. Specifically, those concerns are:

- A primary strategy for excluding competitors is imposing vertical restrictions, including denying a competitor access to a platform. Courts often, however, presume that vertical restraints enhance competition.

- The U.S. Supreme Court has virtually eliminated antitrust liability for tactics such as refusals to deal (denying a competitor access to a critical online platform) and predatory pricing (pricing low to drive competitors out of business), both of which can be used by a dominant internet firm to exclude its competitors.

- Many online services, such as search engines and apps, do not charge individuals for their use. Even if there is no increase in prices to the user, a dominant platform can anticompetitively exclude a competitor. That conduct can harm if the dominant firm then offers lower-quality apps or less advertising after eliminating a competitive threat. But courts have been skeptical of accepting evidence of qualitative harm, as opposed to evidence of higher prices.

- The direct victims of anticompetitive acts (the target of exclusionary conduct or an acquisition) in digital platforms will often be small or potential competitors that could develop into disruptive forces, as Google did to the once-dominant search engine Alta Vista in the early 2000s. Challenging conduct that affects potential competitors can be difficult because courts focus on the likelihood of harm and not its size. Courts generally require that it be more likely than not that the new company would have been successful. But even if a competitor is somewhat less likely than not to succeed, its acquisition by a dominant platform (or being forced from the market) is still anticompetitive if the potential competitive benefit would be substantial.

- Some digital markets are two-sided transaction markets, such as credit card companies that provide necessary services to both merchants and customers to make transactions possible. The Supreme Court has limited the ability of plaintiffs to prove harm directly, required evidence inconsistent with economic theory, and defined a “two-sided transaction market” so broadly that it might be misconstrued to apply to almost any digital platform.

Recommendations

Congress, not the courts, is the last word on the antitrust laws. The statement calls on Congress to “revise the antitrust laws so that they are no longer inconsistent with modern economic thinking.” The statement then offers broad areas of potential reform:

- Nullify existing precedent that limits antitrust actions

- Clarify that the antitrust laws protect potential competition

- Establish legal rules that, in appropriate cases, require defendants to prove their conduct does not harm competition

- Increase penalties and enforcement resources

Although the audience for this statement is Congress, the courts do not need to wait for legislation. Judges have become complacent in relying on economic principles that are outdated or incorrect. The statement also should embolden enforcers to be more aggressive in challenging bad legal decisions and advocating for courts to modernize their thinking.

The evidence is clear, and the harm from lax antitrust enforcement is real. Policymakers and the courts need to act now to ensure we have vibrant competition throughout the economy and in digital markets particularly.

List of signees to the statement

- Jonathan B. Baker, research professor of law, American University Washington College of Law

- Joseph Farrell, professor of economics, emeritus, University of California, Berkeley

- Andrew I. Gavil, professor of law, Howard University School of Law

- Martin S. Gaynor, E.J. Barone University Professor of economics and public policy, Carnegie Mellon University

- Michael Kades, director of Markets and Competition Policy, Washington Center for Equitable Growth

- Michael L. Katz, Sarin Chair Emeritus in strategy and leadership, Haas School of Business, professor emeritus, Department of Economics, University of California, Berkeley

- Gene Kimmelman, senior advisor, Public Knowledge

- A. Douglas Melamed, professor of the practice of law, Stanford Law School

- Nancy L. Rose, Charles P. Kindleberger Professor of applied economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Steven C. Salop, professor of economics and law, Georgetown University Law Center

- Fiona M. Scott Morton, Theodore Nierenberg Professor of economics, Yale School of Management

- Carl Shapiro, professor of the Graduate School, Transamerica Chair in business strategy emeritus, University of California, Berkeley