Overview

Efficient, effective, and responsive income support programs can reduce economic inequality and support economic mobility. If targeted effectively, these programs can help children, families, and workers meet their needs and provide the greatest return on investment to enhance broader social welfare. Over the past 20 years, economic inequality has been rising in the United States, and the policy choices enacted in the second Trump administration’s budget reconciliation bill are likely to exacerbate that divide.1

As state policymakers determine how to meet the growing needs of their constituents, they should optimize existing sources of support available to help the lowest-income children and families meet their needs. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families block grant program is the primary source of federal funds available to states, territories, the District of Columbia, and federally recognized Native American tribes to provide temporary direct cash assistance to families with children experiencing deep poverty.

Currently, the program provides too few dollars to too few families, limiting its potential impact. Today, only 1 in 5 households that meet the eligibility criteria for TANF-funded direct cash assistance benefits receives it.2 Further, when families are able to access the benefits, the amounts are far too low. In Texas, for example, a single parent with two children could qualify for a maximum benefit of $353 per month as long as their monthly income stays below $188, in addition to other requirements, many of which require significant time and energy to satisfy.3

Although the program is imperfect, it provides valuable administrative infrastructure to reach some of the U.S. families living on the lowest incomes. TANF recipients are overwhelmingly children and single mothers; until U.S. policymakers develop more effective approaches for investing in these populations, TANF cash assistance to eligible families during crucial development years can help set them on a path for future success.4

This mismatch between family need and TANF access translates to millions of children who would otherwise be eligible for the program not having the resources to meet their basic needs. The result is an increasing number of children being raised on exceptionally low incomes—in some cases, less than $2,000 a month, or $24,000 a year for a family of three. In 2023, federal and state TANF programs had access to roughly $33 billion in funding, split about evenly between the federal and state governments.5 Yet state TANF programs invested less than a quarter of total TANF spending on direct cash assistance programs.6 Instead, states spent these dollars on other state programs, including priorities that do not support the TANF program’s goals and that are often a poor investment of government resources that do not provide the same return on investment that investing in children can.

This means millions of children across the United States are being raised without their basic needs due to policy design rather than a lack of dedicated funds at the state or federal level. Beyond the direct harm of insufficient resources on child development, limiting eligible families’ access to TANF dollars also limits their household consumption and, in turn, economic activity. Indeed, research suggests a loss of one dollar in TANF direct cash assistance per year costs society $8 per year.7

To address this policy shortfall, we recommend states spend a greater portion of their dedicated TANF program funds on direct cash assistance to the children living on the lowest incomes. The TANF program has so far escaped the hatchet of the Trump administration’s zealous pursuit of reductions in federal spending on programs that support the lowest-income Americans, suggesting it may just survive a while longer. While these dedicated funds are available, states should take advantage of them. They can do this by increasing benefit amounts or providing benefits to a larger portion of eligible families. This would enable the program to support families in deep poverty better meet their basic needs.

This report begins with an overview of the history and current implementation of the TANF program, followed by a review of the relevant economic literature on the public benefits of investing in children and families living on low incomes. This report also features quotes from parents with direct experience interacting with and receiving benefits through state-level TANF programs. We close with policy recommendations that states can implement to improve the effectiveness of their TANF programs to support children and families’ economic security and well-being. Above all, though, states should increase the amount of direct cash assistance families receive by:

- Increasing the proportion of federal and state TANF funds spent on direct cash assistance

- Increasing the benefit amounts they provide to children and families to elevate families out of deep poverty

- Ease the benefit phase-out rates for families in near poverty

- Reduce administrative burdens for accessing state TANF programs, especially direct cash assistance

As this report will detail, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families alone cannot solve child poverty in the United States. The TANF program provides critically needed support to some of the lowest-income families with children, but more could be done with the existing program. To optimize TANF funds to meet residents’ immediate needs, states should reform and invest in the program as a bridge to longer-term solutions.

An overview of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families block grant is the primary source of federal funding for states to provide direct cash assistance to low-income families with children to help meet their basic needs.8 There are no federal rules that require states to provide a cash benefit, but all states do because it is an efficient and effective policy that is cheaper to administer than other types of public benefits.

As of 2025, the federal government delivered $16.6 billion a year in TANF block grant funding to state governments to administer state and local programs that provide a range of services to families with low incomes, including direct cash assistance or “non-assistance” services such as child care or work supports, sometimes referred to as in-kind.9 Not all in-kind spending is created equal, however, as some states have utilized TANF funds to support in-kind services that are only tenuously tied to the goals of the program. As of 2025, direct cash assistance makes up less than a quarter of all states’ TANF spending. States are expected to supplement federal TANF funds from their own coffers, referred to as maintenance-of-effort funding, typically around $15 billion a year.10

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families is a small program compared to others, such as the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program that serves 42 million participants per month and cost roughly $113 billion in 2023.11 In 2024, only 2.7 million recipients, including 1.9 million children from 1 million families, received direct cash assistance from a TANF program per month using federal and state TANF funds.12 Each state runs its own TANF block grant funded program; the federal Office of Family Assistance, housed within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families, administers the funds for the program and is responsible for providing limited oversight.13

The TANF block grant was established as part of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (see box, below). This law was the culmination of decades of socially fraught debates over “welfare reform,” starting with structural exclusions in many income support programs’ New Deal era foundations, to more mainstream political discourse through President Ronald Reagan’s perpetuation of a racist “welfare queens” trope during his 1970s political campaigns,14 to President Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign promise to “end welfare as we know it.”15 Much of the welfare reform rhetoric centered around how much single mothers should be expected to work in paid employment and “whether the Aid to Families with Dependent Children entitlement program itself had disincentives to paid work and raising children in two-parent families.”16

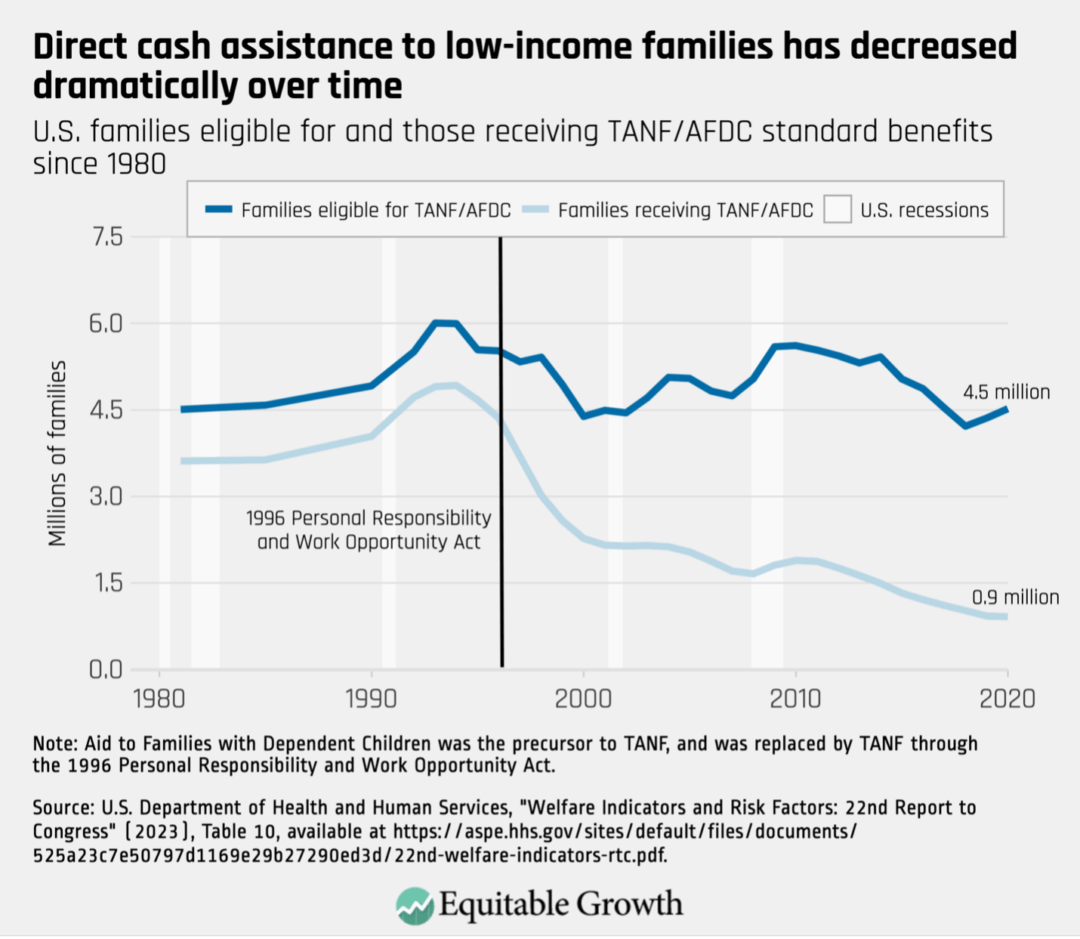

Analysis by the Congressional Budget Office published in 2022 found that the introduction of work requirements on direct cash payments primarily functioned as a way to reduce government spending through the reduction of program participants.17 Additional research that compares states that shortened lifetime limits to states that did not do so in the wake of the Great Recession of 2007–2009 found that strict time limits on TANF participation did not accomplish the stated goal in 1996 of moving people off public benefit programs and into work, instead finding that time limits on average had no impact on labor supply and only served as a vehicle to reduce the number of families tapping into needed TANF benefits.18 Indeed, the number of families receiving direct cash assistance dropped rapidly after the TANF program was introduced in 1997, to the detriment of children living on low incomes.19 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The introduction of a 60-month federal lifetime limit on receiving direct cash assistance benefits and, more consequentially, the federal enforcement of work reporting requirements are key drivers in the caseload reduction envisioned when the TANF program replaced the earlier Aid to Families with Dependent Children entitlement program.20 Aid to Families with Dependent Children (in existence from 1935 to 1996) reached a majority of families living in poverty during its final 20 years, covering between 60 percent and 82 percent of eligible families. By 2019, direct cash assistance funded by Temporary Assistance for Needy Families supported roughly one-seventh the number of recipients served by the AFDC program in 1993.21

Structuring TANF funds as a block grant gives states expansive discretion over the use of the funds. The federal legislation that established the TANF block grant did not define “needy,” allowing states to determine which populations qualify. This has led to spending on programs other than direct cash assistance that are not directly related to the program’s goals—sometimes including spending on households making up to 400 percent of the federal poverty threshold, or $106,600 for a family of three in 2025.22

Nonetheless, few families with children who are eligible for TANF-funded direct cash assistance receive it, and when they do, the benefits are not large enough to support their material needs. In a typical year, only 20 percent of eligible families receive TANF benefits,23 and few states provide a large enough cash benefit to increase a family’s income to 50 percent of the federal poverty threshold, or $13,325 annually for a family of three (a single parent with two children) in 2025.24

In fact, it is so difficult to access direct cash benefits provided by state TANF programs that around half of all households that receive TANF funds receive them for the “child only.”25 For these households, the adult or adults in the household are not considered in the calculation for the benefit amount. Child-only cases can arise when a child lives without a parent present (usually, the children live with relatives or a designated guardian) or when the parent is deemed ineligible for TANF benefits for certain nonfinancial reasons that can vary state by state.26 In the cases where parents do receive TANF cash assistance, they are predominantly single mothers, who tend to have a high school education or less, with children under the age of 12.27

The benefits of direct cash assistance and the roadblocks to its effective distribution

The benefits of providing cash directly to families is widely accepted.39 Cash can be deployed quickly and efficiently, making it easier to administer and receive than in-kind benefits. Cash also can be cheaper to administer than other types of in-kind benefits, and it allows recipients to optimize their funds to best meet their family’s unique needs, empowering them to set their own budget priorities.

The benefits of cash in helping families meet their immediate needs have been further illustrated by recent pilots across the country to provide guaranteed income to families, as well as the success of even modest payments from the short-term expansion of the Child Tax Credit in 2021 under the American Rescue Plan.40 The short-term CTC expansion made the credit fully refundable to parents who previously had incomes too low to qualify for the traditional version of the credit. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the roughly $250 to $300 monthly payments to newly eligible families led to an immediate and historic reduction in children living in poverty.41 Once the expansion ended and direct payments stopped, the number of children living in poverty doubled, from its historic low in 2021 of 5.2 percent to just higher than 12 percent in 2022.42

Compared to guaranteed income programs or the expanded Child Tax Credit, direct cash assistance provided through federal TANF block grant funding has a limited impact due to the small size of the payments. This comports with research that suggests that most safety net spending is directed to families with earnings and incomes above federal poverty guidelines, primarily due to 1996 welfare reform and later expansions of tax credits for families with children that have a more meaningful impact on household budgets at higher income levels.43 Indeed, research suggests that, overall, the totality of U.S. income support programs struggles to support the very poorest families.44

TANF-funded programs provide too few dollars to too few families

“So, under $200 a month for two people. Like, that’s not enough money. Like, you know, you gotta, like, scrape. You gotta find the deal … I do extreme couponing. Let me tell you that … helps a lot. And, yeah. I could get diapers anywhere from, like, the pack would be, like, $30. I can get it down from anywhere from $15 to $10. I’m telling you, the coupons are out there … But it’s not enough money. It’s not enough, but, you know, I’m not greedy. It’s just like, you know, the decrease for me, you know, then I’m a single parent. It’s not like I have help. It’s not like I’m gonna ask anybody for anything, you know? So, it’s just like, yeah. That was, that was tough.”

— Former TANF recipient, New York

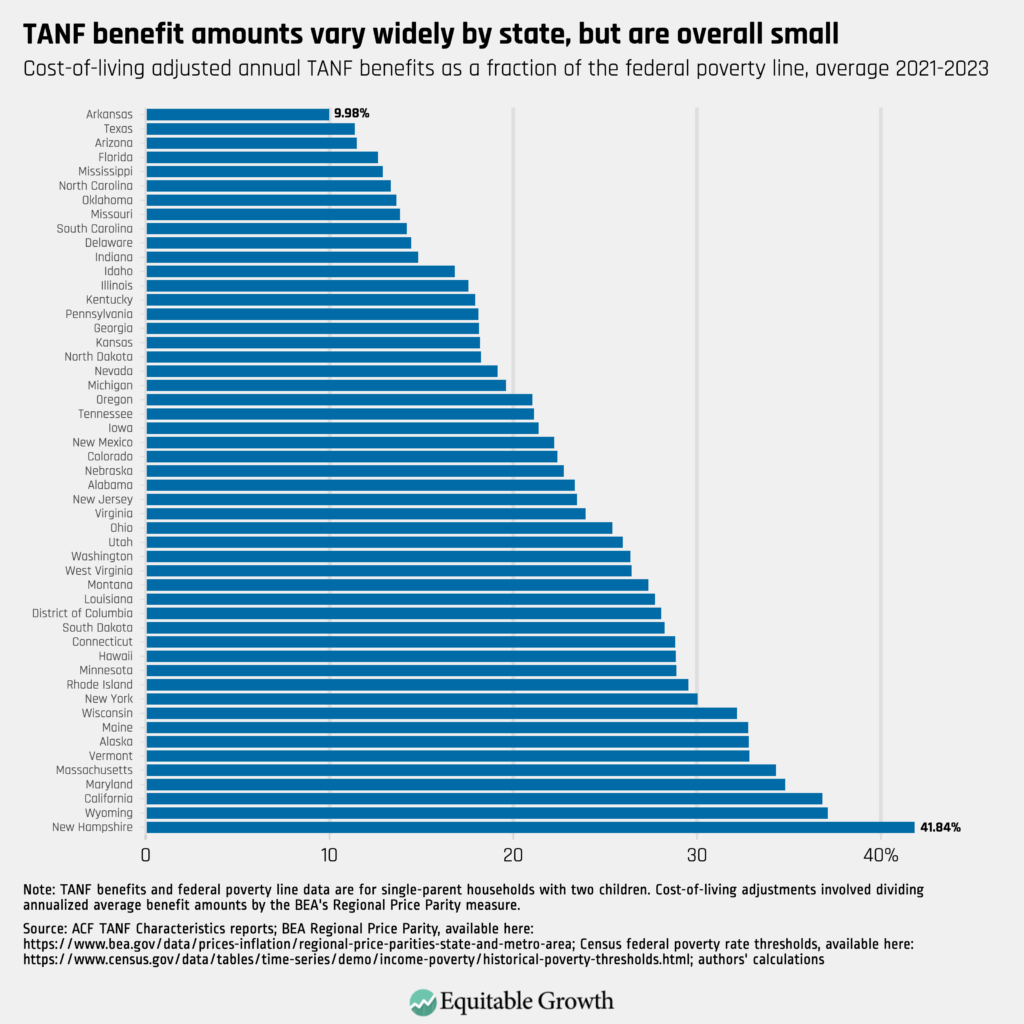

TANF direct cash assistance benefits do not reach enough families that are living in poverty and eligible for the program. Once they are able to participate in the program, however, benefit amounts are very low, ranging from $204 dollars a month in Arkansas to $1,243 in New Hampshire for a single parent with two children (in July 2023).45 States have control over how much support they provide to families within the federal 60-month lifetime limit, although some states have implemented shorter time limits.

The small size of the current cash benefits limits the potential impact the funds could have on families navigating a period with extremely low or no income. Some research on state-specific enrollment trends suggests that families enroll in state-level TANF programs after they have exhausted other income support programs, such as Unemployment Insurance.46 In 2023, families with two children and one adult living on $2,045 a month, or an annual income of $24,549,47 were at the federal poverty threshold, while the national average monthly benefit for all family sizes receiving TANF funds was $650 per month in 2023. (See Figure 2.) Thirty-three states and the District of Columbia did not allow monthly family household earnings of more than $1,000 a month for a family of three in 2021, while nine limit it to $500.

Figure 2

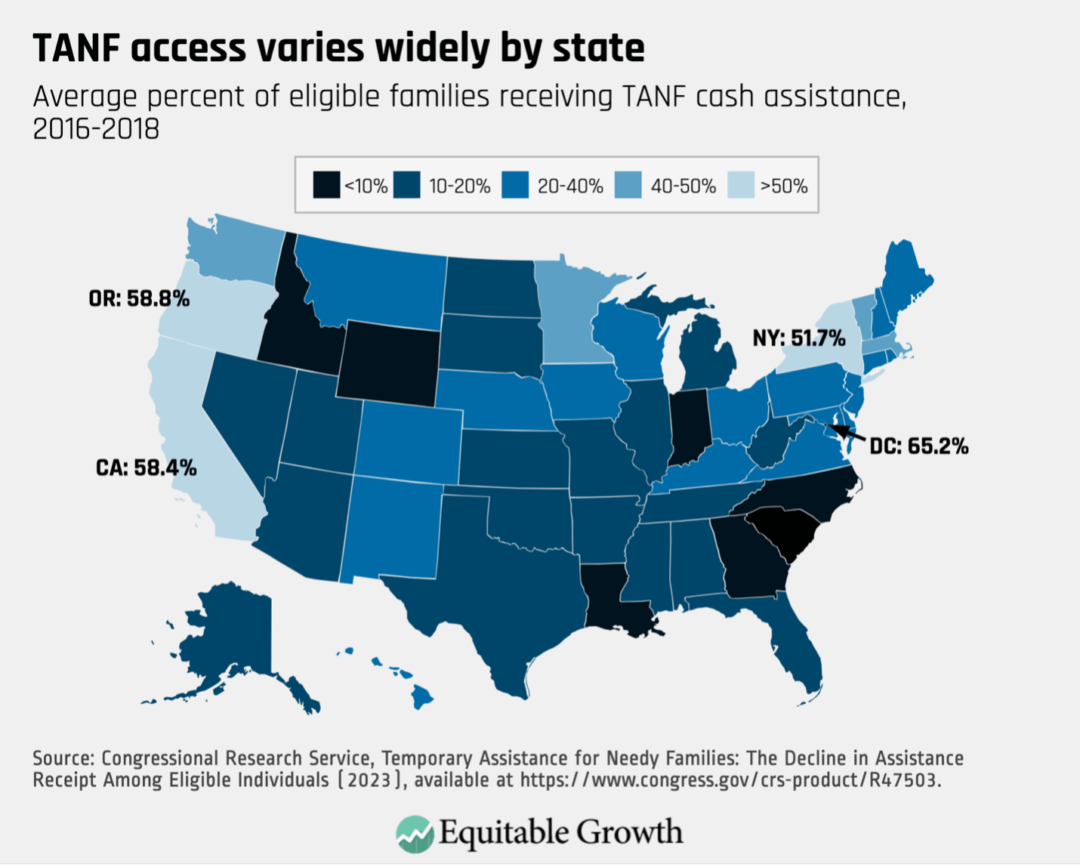

There is wide variation in the size of state programs and access to direct cash assistance. Some states provide direct cash assistance benefits to more than half of their eligible families, as is the case in California, Oregon, and New York, while other states, including Louisiana, Idaho, and Indiana, provide direct cash assistance benefits to fewer than 10 percent of their eligible populations. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

State TANF programs vary in size because they often are not tied to need. The largest program, in California, served more than 1.1 million families, including more than 800,000 children, in an average month in 2024 and covered more than two-thirds of eligible families in the state.48 States, including North Dakota and Wyoming, served fewer than 1,500 families in an average month in 2024 and covered only 7 percent to 12 percent of eligible families.49

In fiscal year 2023, White and Black families each comprised roughly 25 percent of federally funded TANF direct cash assistance, while Hispanic families (of any race) comprised 38 percent, and recipients who identify as American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, multi-racial, and “unknown” accounted for the remaining cases.50 These proportions are partially driven by California’s enrollment, where almost 13 percent of the nation’s children live and, of those, more than 50 percent are Hispanic or Latino Children.51

Access to direct cash assistance funded by the TANF block grant is disparate by race, with research finding that states with larger populations of Black Americans have programs that provide fewer dollars to fewer families with high administrative barriers to qualify.52 Unsurprisingly, then, 41 percent of Black children in the United States live in states that provide direct cash assistance to fewer than 10 percent of eligible families, compared to 34 percent of Latino children and 29 percent of White children.53

Across the United States, funding and availability of income support programs for families living on low incomes is so low that families must cobble together benefits from multiple programs to meet their basic needs. Ninety-five percent of families receiving direct cash assistance benefits funded by Temporary Assistance for Needy Families also receive federal medical assistance such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and almost 85 percent of families also receive food assistance from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program at an average benefit size of $564 dollars a month.54

Many families who receive cash assistance through the TANF program are housing insecure due to their very low incomes and the limited reach of federal housing and rental assistance programs. The median cost of housing for renters in 2023 was $1,406—greater than any states’ TANF benefits—and only 10 percent of families receiving federal TANF-funded direct cash assistance are also receiving federal housing support.55 Due to limited funding by Congress, federal housing and rental assistance only supports one 1 in 4 families with children that qualify.56 Yet stable housing programs play a primary role in helping families become more economically secure. Housing instability can be detrimental for children’s outcomes, and research suggests that the decline in TANF direct cash assistance since the late 1990s may be “an important driver in homelessness,” compared to access to nutrition assistance or increased generosity of the Earned Income Tax Credit.57

The impact of work requirements and navigating the administrative burden of public benefits

“It was a little confusing to me because it was so, so many questions and so much information that was needed … Asking for so much information can be overwhelming. And some people are cautious with having to give up certain personal information”

— Former TANF recipient, California

During the passage of the 1996 welfare reform law, multiple members of Congress spoke out against the limited exemptions to single parents with children under the age of 6 in favor of a prior version of the legislation that provided the exemption to single parents with children under the age of 12.58 They were right to be concerned: In fiscal year 2023, more than 75 percent of the children in families receiving cash assistance from federal TANF funds were under the age of 12.59 Work reporting requirements also introduce increased administrative complexity to the provision of public benefits.

The flexibility for single parents and the exemption for parents with newborns do not sufficiently accommodate the demands on parents. Analysis produced by The Hamilton Project analyzing U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data suggests that on average, mothers in the United States with children aged 12 and under spend 8.6 hours a day caring for their children.60 Single mothers with very young children or multiple children likely spend an even greater portion of their day providing care, and newborn babies require near-constant care, as do children with disabilities that require specialized care from family members.

“I couldn’t find nobody to watch him. So, [I was told] to bring him in for the one-day training, and the workers were, like, rotating watching him. And at this time, I felt so bad. He was, like, four or five months old. You know? He’s a little baby. But they said, you know, you have to do what you have to do. I wish that they would give people child care, like, a month in advance prior to education status, prior to work status, prior to training status.”

— Former TANF recipient, New York

For the single mothers who lost benefits due to the introduction of work requirements, they and their families were left in deep poverty, and even those who were able to find employment did not experience a meaningful increase in their incomes. The requirements imposed on families eligible for direct cash assistance funded by the TANF block grant likely played a role in increasing the number of families with children living deep poverty due to the program removing families before they found work and deterring their program participation.61

The introduction and strict enforcement of work reporting requirements, alongside the state-level work participation rate, shapes program demographics and dictates access to direct cash assistance benefits funded by the federal TANF block grant. This is despite evidence suggesting that work requirements are more effective at discouraging participation in public benefit programs than encouraging work. The federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour also hampers families’ ability to meet their basic needs, as working full-time at minimum wage only generates a yearly income of $15,080—less than 50 percent of the federal poverty threshold for a family of three.6263

The racist roots of work requirements to obtain public benefit programs have been well-documented.64 Work requirements fail to consider the labor market discrimination that Black workers in particular have been subjected to.65

Additionally, researchers have found that most parents who participate in state TANF programs are earning incomes before and after receiving TANF benefits, but they face a labor market that subjects them to low-pay work with inconsistent schedules, limiting their ability to work their way to economic security.66 Research on families that left the TANF program in Georgia (which has a state-set 48-month lifetime limit) found that they often end up in jobs with pay that leaves them below the poverty line.67

Furthermore, many families have little to no savings to tap into between bouts of employment, necessitating them to enroll in the TANF program. Almost all states have asset limits, or limits to personal wealth, to qualify to receive TANF benefits that are as low as $1,000 in some states.68 Some states also have a vehicle asset limit, limiting families access to a car even though many people need one to get to work.69

The work requirements imposed on parents receiving TANF-funded benefits can vary drastically by state. Scholars have detailed the ways in which states can game work requirements.70 Some states have learned that they can shift beneficiaries that are unable to meet the federal TANF work requirements to assistance funded solely by the state—and thus outside of the federal requirements.71 Other states have chosen to implement more stringent work requirements on their beneficiaries. States that fail to enforce the required levels of work on participants receiving benefits funded by federal dollars risk losing access to their federal funds.

Research on income support programs, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and Medicaid, shows that the introduction of work reporting requirements on these programs greatly limits the efficacy of programs. Economists have found SNAP work requirements have no impact on labor supply but push many people off the program and hamper its ability to reach the children and families with the greatest need for nutrition assistance—the hungriest families—because those families struggle the most to comply with the work reporting requirements.72

In 2015, to receive TANF benefits in Michigan, for example, applicants were required to complete four visits to an in-person regional employment office. Sixty percent of initial applicants did not receive benefits due to an inability to meet application requirements. Researchers found that even personalized reminders intended to nudge potential beneficiaries to complete their applications after initial visits and to attend their remaining appointments did not increase appointment attendance.73 This suggests that the large transaction costs associated with applying for TANF benefits were a considerable obstacle to families both in completing applications and obtaining benefits.

Work reporting requirements do not help families secure higher incomes, and in some cases, they can result in families having to exist on even smaller monthly incomes. Research on Kansas’ 2011 increase in punitive enforcement of work requirements for their state TANF program found that recipients moving off the program was not associated with any change in an adult labor force participation or attachment.74 The researchers did find, however, that work for adult recipients was inconsistent, both before and after leaving the state’s TANF program, likely due to barriers to finding stable work.

Four years later, the result in Kansas was thousands of families losing access to direct cash assistance provided by Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, which, in turn, meant they had to learn to live on incomes even lower than the small TANF benefit amount they would have received if they had not lost access (some as low as $2,100 to $1,300 a year). Engaging in the labor market costs money: It requires appropriate clothing, transportation costs, and child care. When families are abruptly removed from income support programs without adequate pathways to address those shortfalls, it is highly unlikely a parent can afford such costs without some help.

Perversely, families with children that receive direct cash assistance are sometimes punished for work by the steep phase-out rates of TANF benefits. In Washington state in 2019, for example, large families eligible for TANF benefits (typically, single parents with multiple children) faced a reduction in benefits of up to 50 cents for every dollar earned, making the trade-off between hours worked, earnings, and benefits for families on tight budgets even harder.75

Aspects of the 1996 implementation of the Connecticut Jobs First program could serve as a model for adjustments to state phase-out rates.76 The program broke from normal practice by allowing TANF recipients with earnings to retain their entire TANF benefit as long as earnings were below 100 percent of the federal poverty line, as set by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Research on the program found it increased earnings and employment in the short and long term.77

Conversations with former TANF recipients revealed how work requirements and eligibility for the program were often unhelpful or confusing. One recipient, a single mother in New York, talked about her difficulties scheduling job interviews and training without having secured day care for her child, a service her TANF office would provide only after she secured a job. She described the anxiety she felt as the deadline to find work approached: “When it came down to that, I was sweating bullets. I didn’t know what I’m going to do.”

The perils and promise of the TANF block grant

During the passage of the 1996 welfare reform law, supporters of the bill repeatedly emphasized that the block grant structure would provide states flexibility in how to utilize the funds to best support their constituents.78 That flexibility does provide states with considerable leeway in how to allocate their TANF block grant funds—including in ways that may not be true to the original purpose of the program.

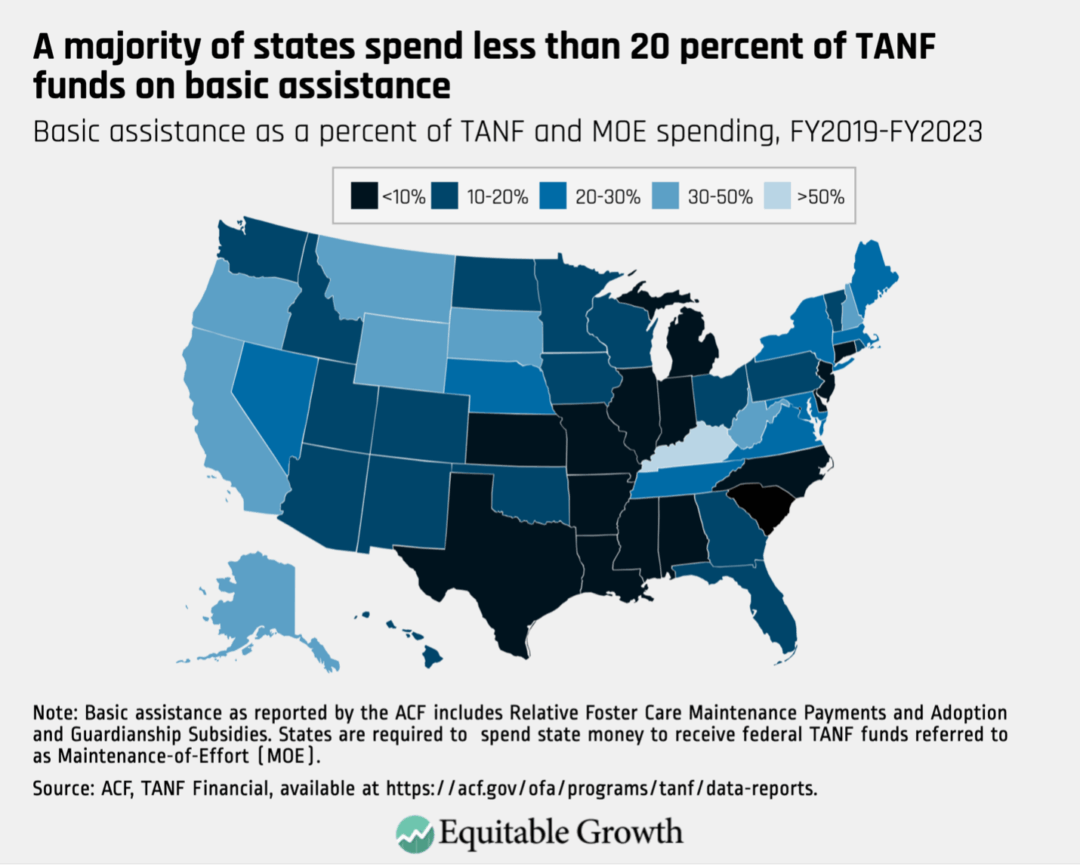

When the TANF block grant was first introduced, a majority of funding—more than 75 percent—went directly to children and families as checks or vouchers to meet household needs, such as child care.79 Since 1996, state spending on assistance other than direct cash assistance has increased, reducing state spending on TANF direct cash assistance to families from $31 billion (84 percent of total spending in 1996, under its predecessor the AFDC program) to $7 billion (23 percent of total spending) in 2019, according to a 2022 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office.80 According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Family Services, which collects and hosts the data, most states spend less than one-fifth of their federal and state TANF funds on direct cash assistance.81 (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Over the TANF block grant program’s lifespan thus far, states have decreased spending on direct cash assistance in lieu of other forms of nonassistance services, such as high school equivalent courses, secondary and post-secondary education, adult education, career and technical training activities, child care, refundable tax credits, child welfare services, and funding pre-Kindergarten and Head Start classes—all of which support the TANF program’s statutory goals when spent on children and their parents living on low incomes.82 Some nonassistance spending, however, funds state priorities that may be only tenuously related to the statutory goals of the TANF program. In 2023, states reported spending $23 million of federal funds and $109 million in state matching funds on services categorized as “other,” or nonassistance spending that could not be included in the 19 other reported categories.83

This happens in part because unlike direct cash assistance, which mandates work requirements and sets time limits, when states provide in-kind benefits to individuals and families, they are not counted toward the lifetime benefit limit or the state’s reported work participation rate. This exemption likely contributes to states increasing spending on nonassistance or in-kind services.

The block grant structure also enables states to accumulate unspent and unallocated funds for future spending, even though families in their states may struggle to meet their needs today. In 2023, more than $7.7 billion federal dollars were left not allocated to support any programs, with New York and Pennsylvania alone reporting more than $1.6 billion and $1.2 billion, respectively, in reserves—a bulk of which was carried over from previous years.84

This ability to accumulate funds leads to states treating federal TANF dollars like a slush fund. Mississippi, for example, infamously spent millions of its TANF block grant dollars on a volleyball stadium at the behest of former professional football player Brett Favre.85 Oklahoma uses TANF dollars on marriage counseling for families regardless of their income level,86 while Michigan funds merit scholarships for students from middle- or high-income families with TANF funds.87 Since 2017, at least $100 million has been diverted to support crisis pregnancy centers, which are facilities that are typically staffed by volunteers without medical training and offer counseling and support to pregnant individuals with the goal of dissuading them from getting an abortion and pushing them toward parenthood or adoption.88 Crisis pregnancy centers have been shown to delay appropriate medical care, which can negatively impact maternal health.89 This occurs because there is scant federal oversight of state spending of federal TANF dollars.90

In response to the Mississippi spending scandal and other reports of TANF block grant dollars being used for program spending that is only tenuously connected to the program’s statutory purposes, in 2023, the Biden administration released a notice of proposed rulemaking intended to strengthen the program’s focus on supporting families and reduce administrative burdens.91 Additionally, the rule would have established a ceiling on the term “needy,” in response to documented reports of states’ TANF programs providing support to families with incomes up to 400 percent of the federal poverty rate, or $106,600 for a family of three in 2025.92

The proposed rule was ultimately withdrawn before it was finalized, on January 14, 2025.93 The administration reportedly needed additional public input, despite receiving more than 7,000 comments from a broad range of stakeholders, and wanted to focus on implementing TANF provisions included in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023.94 This law included provisions that hamper state-level flexibility in meeting the states’ required work participation rate and provided funds for five states to implement intriguing pilot programs.95 These programs would have allowed the states to measure success with work and family outcomes based on employment and retention of employment after 6 months of exiting the program and family stability and well-being—measures that would have been decided by the U.S. secretary of Health and Human Services—as opposed to work participation rates.

In March 2025, the Trump administration announced that it would not honor the five states selected by the Biden administration and would require all interested states to apply again under the new Health and Human Services secretary.96 In May 2025, the new pilot application released by the Trump administration emphasized a focus “on promoting work and reducing dependency.”97

Although the TANF block grant structure enables states to misuse it, it also enables state-level innovation to get the dedicated funds to work for children and families living on exceptionally low incomes. When traditional TANF direct cash assistance is not being adequately deployed, unlocking TANF funds for families living on low incomes with children in any capacity is better than allowing them to pile up in state coffers or be disbursed for purposes that do not support those with the greatest need.

Advocates in Michigan, where almost 18 percent of children live in poverty, have taken advantage of the flexibility of the program to the benefit of pregnant individuals and their very young children.98 Before these advocates got to work, only about 1 in 10 families that were living in poverty were able to access direct cash assistance through the basic assistance program, according to analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, for a maximum benefit of $492 for family of three (a single parent and two children) in 2023.99 In 2023, the state spent less than 8 percent of its TANF state and federal funds on direct assistance.100

Then, in 2024, Michigan’s Rx Kids program, first launched in Flint, Michigan in January of that year, began providing universal, unconditional, and predictable cash benefits to all families in Flint with a newborn child.101 Billed as the nation’s “first community-wide maternal and infant cash prescription program,” every pregnant individual—no matter their income—is provided $1,500 mid-pregnancy and then $500 a month for each subsequent month for the first year of the baby’s life.102 The program has achieved almost 100 percent uptake and is on track to eliminate deep infant poverty in the community.

The objectives of the Rx Kids program is underpinned by earlier findings from Equitable Growth grantee Alexandra Stancyzk, who analyzed data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation to document the negative income impacts associated with the months around the birth of a baby, particularly for single mothers.103 Rx Kids leverages the federal TANF block grant’s flexibility and the generosity of private philanthropy and is thus able to utilize this funding by taking advantage of so-called nonrecurrent short-term benefits, a type of nonassistance support under the TANF program. By utilizing nonassistance support, families can receive funds without triggering the work reporting requirements or accruing time limits on the 5-year eligibility window—meaning if they need additional support in the later years of a child’s life, they can access it.

Indeed, centering the Rx Kids program in Flint, a very poor city, provides a targeted form of universal income support. By providing universal support, the program also reduces stigma and eases enrollment processes that typically reduce the uptake of public benefit programs. Additionally, in Flint, families participating in Rx Kids reported improvements in their housing security in 2024, when communities in the rest of Michigan reported increases in housing instability.

In 2025, the program expanded to Kalamazoo, Michigan and the Eastern Upper Peninsula of Michigan. As of April 29, 2025, more than $8.5 million in TANF funds have been “prescribed” to more than 2,100 families to support more than 1,600 babies born. More than half of the families served by Rx Kids live in households with annual incomes below $20,000 a year. And in 2025, the Flint & Genesee Group, a partnership between the Chambers of Commerce in the cities of Flint and Genesee and other local economic development-oriented local organizations, reported that the $7.5 million invested in Flint from Rx Kids direct cash payments produced an estimated $11.8 million in total economic impact in the city of Flint.104

States should spend more of their TANF funds on direct cash assistance to support children and families living on low incomes and support their local economies

If TANF-funded direct cash assistance reached the same portion of families eligible for benefits as its predecessor program did in 1996—68 percent—then 2.38 million more families would have received cash assistance in 2020, according to calculations by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.105 The decline in TANF program participation has resulted in millions more children across the United States being raised on exceptionally low incomes, of $2,000 or less a month.

Providing direct cash assistance to families with children is the most efficient way to support children and families’ economic security and well-being. It is an immediate way to alleviate some degree of material hardship, childhood hunger, and housing insecurity, and empower families to make the best decisions for their family’s needs.

But direct cash assistance also can support local economic growth by immediately increasing the consumption of households living on low incomes and enabling them to purchase goods and services that help them meet their basic needs. It can thus serve as a stimulus to local economies where it is introduced.106 Direct cash assistance can deliver positive ripples through a local economy since local businesses generate higher revenues, leaving the local economy better off.107

That increase in household consumption helps these families meet their basic needs, and also then contributes to the improved well-being of the members of the family and, importantly, the children. Investments in children have been shown to lead to increased earnings and higher tax revenues over their lifetimes, with increased benefits the earlier the intervention.108 Researchers estimate that the return on investment in the long run for programs that support very young children is as high as $10 for every one dollar spent.109

Providing cash directly to families can also be much cheaper to administer, compared to in-kind support, when not paired with strict work reporting requirements. So, let’s dive deeper into why TANF spending supports families to meet their basic needs, provides additional dollars that ripple through local economies, and deliver long-run benefits by investing in children.

Helping families meet their basic needs

“The financial aspect of it definitely helped, in regards to me, you know, not having to struggle, and, like, really live check paycheck to paycheck to paycheck to paycheck at that time.”

— Former TANF recipient, California

Direct cash assistance can support a family’s consumption of goods and services, allowing them to choose how to best allocate their funds to meet their basic needs, and support the local economy to which the additional dollars are introduced.110

New Hampshire offers an insightful case study in this area. In 2017, the state increased the TANF cash benefit amount it provided to families due to its loss of value over time and tied the benefit level to 60 percent of the federal poverty guideline ($1,243 dollars a month, or $14,916 annually, for a family of three in 2023) produced by the U.S. Health and Human Services Department.111

Following the increase in direct cash benefits in New Hampshire, economists utilized the Current Population Survey and TANF caseload, expenditures, and participant characteristics to observe changes based on the increased direct cash benefit generosity.112 They found that single mothers with a high school degree or less who received direct cash assistance reported an increase in consumption—specifically, increased weekly food expenditures that contributed to a reduction in food insecurity, reducing their episodes of hunger. Critically, the increase was not tied to more intense work-activity reporting requirements or eligibility tightening.

Additionally, the researchers observed a small decline in labor force participation among single mothers with a high school education or less. Whatever the case, spending less time doing paid work should be a positive outcome of investments of TANF funding considering the value of time spent childrearing for the development of human capital and future generations’ increased productivity.

While there is less in the literature on how receiving only TANF benefits can impact families’ spending and consumption, there is research that explores the impact of TANF benefits on food security, primarily in tandem with other programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which shows it meaningfully reduces food insecurity and hunger.113

Targeted spending can support efficient government transfers to address the material needs of families facing hardship. Researchers have detailed that low-wealth, low-income families have higher marginal propensities to consume, compared to high-wealth families, meaning low-income families are more likely to change their spending and consumption when they gain access to additional funds.114 Direct cash assistance targeted at low-income individuals and families is more likely to be largely spent in local economies to meet basic needs, boosting total demand and supporting local businesses, compared to higher-wealth individuals and families that are already consuming at high rates.

The provision of direct cash assistance through mechanisms other than state TANF programs—such as through the temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit in 2021, for example—can provide some insight into how families utilize more generous provisions of direct cash assistance. Overall, research on international guaranteed basic income interventions has found that direct cash assistance is associated with beneficial outcomes in food security, well-being, and education.115 Unsurprisingly, when families receive cash to help meet their needs, they spend it on their children or on what they need to support their families such as rent, utility bills, and transportation.116

Research conducted on how families spent the 2021 temporary expansion of the refundable Child Tax Credit found positive impacts on both household consumption and child developmental outcomes.117 Analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Purse Survey suggests that most CTC recipients spent the additional money on food and other basic needs, such as rent, utilities, and clothing.118 Some of that money also was spent on paying down debts or put into savings.

Notably, as many as 40 percent of recipients spent all of their CTC funds without saving any, according to the Households Pulse Survey, which suggests both that families had unmet needs and generated immediate spending with their credits. It also suggests that for the purposes of immediately alleviating material hardship and child hunger, the temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit and making it fully refundable was fairly well-targeted.

“Now SNAP is only good for food. Right? Which doesn’t include [Infant] formula. So, we were okay with that as far as the baby, but it didn’t help. SNAP and Medicaid don’t help with Pampers and wipes. And, you know, [my daughter] would get sick and need some medicine and stuff like that.”

— Former TANF recipient, Chicago

Additional dollars ripple through local economies

Individuals surviving on exceptionally low incomes tend to have unmet needs, and inequality is a drag on the economy as it dampens household spending.119 Children and their parents may suffer from hunger because they cannot afford enough food or they may wear shoes that are too small, both of which limit their ability to fully flourish and engage fully in the economy. Providing them with additional support, ideally in the form of direct cash assistance, enables them to determine how to best allocate their limited funds to meet their needs, whether that be an increased food budget or additional medicine.

The number of times a government investment circulates in the economy is often referred to as a multiplier effect. While there is limited research on the potential multiplier effect of direct cash assistance programs, researchers and policymakers alike can learn a lot from research on the economic impacts generated by spending on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and from research conducted on other programs that serve low-income families that struggle to meet their material needs.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture found that supporting the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program created a multiplier of 1.5 for SNAP funds in 2016.120 That means for every $1 billion spent on SNAP benefits, the U.S. economy benefits from $1.5 billion of increased Gross Domestic Product, supporting more than 13,000 new jobs. The research also suggests that when targeted to low-income households, the multiplier may be as high as $2 for every one dollar spent.

Those USDA researchers looked at all types of spending by SNAP recipients by type of goods, finding that the largest chunk of their overall spending was on food purchases, though SNAP recipients also spent large parts of their overall incomes on purchases of durable and nondurable goods and health care.121 This suggests that nutrition assistance is cash-like, at least in the sense that SNAP spending on food frees up recipients to spend their other income elsewhere.

Research on government spending and investments generally found a local income multiplier of 1.7 to 2.0, with larger impacts in areas with slower income and employment growth, reducing geographic inequalities.122 Economic impacts were largely concentrated in the geographic area where spending occurred. These results are somewhat applicable to understanding the potential impact of TANF block grant spending on direct cash assistance since it was included in the government spending programs.

Additionally, some separate research on fiscal multipliers during recessions suggests that government spending is a more effective stimulus during recessions than periods of expansion.123 Spending seems to be effective at driving growth during recessions by increasing employment and consumer spending.

Long-term benefits of investing in children

“TANF being able to support me and even with me going to school and not having to worry about finances because I wasn’t working, I was able to actually be here with my daughters and help them with homework and, you know, attend certain curricular activities for them that they look forward to. So, having that support, I’m able to have those experiences with my daughters. And, again, just me being able to be home with them and do work with them and actually be here to support them, you know, within their needs and their growing up, it definitely helped.”

— Former TANF recipient, California

Investing in children provides the greatest return on investment, compared to spending programs targeting other populations. Research also has shown that earlier in life is when investment in children can have the greatest impact on the trajectory of a child’s life.124 This research on the returns to investments in children can help us understand some of the longer-term returns we can gain as a society through targeted income support programs.125

A unified analysis of government welfare policies by Harvard University economists Nathaniel Hendren and Ben Sprung-Keyser sought to calculate the benefit and net cost of government policies, including social insurance, education, job training, taxes, and cash transfers.126 In calculating the net cost, the researchers considered the long-term impacts on the government’s budget and drew on numerous papers to inform their findings for each government program. They found a high marginal value of public funds for investments that support the needs of children, citing “near infinite marginal value of public funds for child health insurance expenditures” such as the Children’s Health Insurance Program and reporting Head Start as a similarly valuable investment. They also found that although programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children had lower marginal value of public funds, that was primarily due to the relationship between spending on these programs being associated with reduced labor earnings and that this “lies in contrast to our finding that many policies spending on children increased later-life earnings.”

Research has found that investing in children and providing them with economic resources can support their needs and can generate down-the-line savings in government spending. Research on the role of family economic security policies on child and family health, for instance, have shown that economic security is particularly important for infants and children, given long-term health ramifications of early life disruptions.127 Evidence shows that more restrictive TANF spending, alongside reduced spending on other social programs, is associated with worse health outcomes, worse access to health care, and higher infant mortality. Research has also found that receiving TANF benefits as a child is associated with improved educational outcomes.128

Using data from 17.5 million Americans, researchers found that access to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and its associated food security, before age 5 is associated with positive adult outcomes, including high levels of human capital, self-sufficiency, quality of neighborhood, and life expectancy, as well as a decrease in the chance of being incarcerated.129

Conclusion: Policy recommendations

Direct cash assistance has been shown to benefit children and their parents living on the lowest incomes, as well as the local economies in which they live. Despite this, not enough eligible families receive direct cash through the TANF program due to states making the benefits challenging to access. For families that are able to access direct cash assistance payments, the benefit amount is too low to help them meet their families’ basic needs. This limits the potential impact this investment in children and families could have.

This is partially due to funding for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families being reduced over time in real terms but also, importantly, to state behavior. In some states, direct cash benefits to eligible families constitutes the smallest proportion of their TANF spending. Both factors limit the potential impact of TANF funds as an investment in children and families.

States can implement programmatic changes to optimize the reach and impact of existing TANF block grant funding on children and families’ economic security and well-being. States have a few ways they can better leverage their funds and increase the amount of direct cash assistance they provide, including by:

- Increasing the proportion of federal and state TANF funds spent on direct cash assistance

- Increasing the benefit amounts they provide to children and families to elevate families out of deep poverty

- Easing the benefit phase-out rates for families

- Reducing administrative burdens

Let’s examine each of these recommendations in turn.

Increase the proportion of federal and state TANF funds spent on direct cash assistance

States should dedicate a larger portion of their federal and state TANF spending on direct cash assistance to provide benefits to more of their state’s eligible families. This may require states reducing spending on programs that only tenuously support low-income children and families, such as reducing or eliminating TANF funding to programs that are not means tested or proven to alleviate poverty.

For example, crisis pregnancy centers typically are not staffed by licensed health care providers and in some cases reportedly “bill $14 dollars and hand out a couple of donated diapers.”130 Analysis by Health Management Associates found that between 2017 and 2023, more than $102 million of federal TANF dollars were allocated to crisis pregnancy centers—roughly the same amount that Kentucky spent on direct cash assistance to support 24,000 individuals in more than 11,000 families (including more than 20,000 children) in 2023.131

States should also take advantage of the flexibility afforded by nonrecurrent, short-term benefit transfers to provide direct cash assistance directly to families living on exceptionally low incomes or who face sudden conditions that remove their ability to generate earned incomes. Michigan’s Rx Kids program is one example of leveraging TANF funding flexibility to support more families with children. Since state spending on nonrecurrent, short-term benefits do not count toward benefit time limits or work participation rates for families, that could be one particularly efficient way for states with excess TANF reserve funds to spend down their unallocated dollars.132

Increase the benefit amounts to children and families to elevate families out of deep poverty

States should increase the benefit amounts to families who receive cash benefits through their state TANF programs. Currently, few state’s benefit level is high enough to move a family out of deep poverty, but more could and should be at that level.

In addition, states should implement automatic cost-of-living adjustments to ensure that their TANF benefit levels keep up with the rising costs of living. Families living on the tightest budgets feel these cost increases the most acutely.

Ease the benefit phase-out rates for families

High phase-out rates for earned income are counterproductive to the goals of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. Introducing more gradual phase-out rates in states that currently have steep phase-out rates would reduce the pain of benefit cliffs and align more closely with the program’s intent. For states with high phase-out rates, such as the earlier example of a 50 percent benefit reduction for every dollar earned through work in Washington state for large families, this could have a meaningful impact on participants.

“I was suggesting that as a future support, a transition period from being active to closing in a more detailed walk through of that process. So, instead of me just walking out that day and being all of a sudden canceled out, there should have at least been a transition period, like, to wean me off [rather than] cut me down to zero instead and just saying, you know what? It’s gone. That aspect would have been great.”

— Former TANF recipient, Chicago

Reduce administrative burdens and barriers to accessing support

While many states work to alleviate the administrative burden of public programs on families, more can be done to support the TANF-eligible population, including alleviating work reporting requirements as much as is feasible under federal guidelines. We heard from parents who were former TANF recipients in New York, California, and Illinois that even when accessing the program through referral or a social worker, many points in the process, from the initial application to when they received their first monthly cash benefit payment, could have been streamlined.

States should remove stringent work requirements that some states have introduced on top of federal requirements and provide more flexibility in the kinds of activities that qualify toward reporting requirements. States should also do away with time limits on benefits that are shorter than the federal 60-month limit and ideally, follow the example of programs such as the District of Columbia’s TANF program, which eliminated the lifetime benefit limit by tapping into state dollars for families who need the additional support.

A note on the production of this report

In the production of this report, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth partnered with national nonprofit LIFT Inc. to interview parents with direct experience interacting and receiving benefits as part of participation in states’ TANF programs. The parents were from different geographic regions, including California, New York, and Illinois.

Founded in 1998, LIFT is a nonprofit organization on a mission to break the cycle of poverty by investing in parents. LIFT’s one-on-one coaching program empowers parents to set and achieve goals that put families on the path toward economic mobility, such as by going back to school, improving credit, eliminating debt, or securing a living wage. In addition to coaching, LIFT parents also receive direct cash infusions to reinvest in their families and goals. LIFT partners with colleges, governments, and health systems to deliver its services nationwide and operates sites in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, DC. You can learn more about their work at whywelift.org.

About the authors

Megan E. Rivera is a fellow for policy and advocacy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Chris Bangert-Drowns is a research assistant at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the former TANF recipients in New York, California, and Illinois for graciously agreeing to interviews to inform the production of this report with their expertise. The authors thank LIFT Inc. for assisting in the coordination of interviews with parents and the review of prior drafts of the report.

We appreciate the generosity provided by the following individuals, who shared their insights and advice and/or reviewed a draft of the report: Scott Allard, Ashley Burnside, Alix Gould-Werth, and Shilpa Phadke. We thank Emily Ruskin for providing guidance and feedback. We thank Ed Paisley and Emilie Openchowski for providing expert editing and Maria Monroe and Shannon Ryan for design support. Any errors of fact or interpretation remain the authors’.

This report was produced with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to our advisors or funders.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. Austin Clemens, “Slow wage growth is the key to understanding U.S. inequality in the 21st century” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2025), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/slow-wage-growth-is-the-key-to-understanding-u-s-inequality-in-the-21st-century/; Howard Gleckman, “What Will The Tax Provisions Of The Big Budget Bill Really Do?” (Washington: Tax Policy Center, 2025), available at https://taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/what-will-tax-provisions-big-budget-bill-really-do.

2. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “22nd Welfare Indicators and Risk Factors Report to Congress” (2023), available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/22nd-welfare-indicators-risk-factors-report-congress.

3. “TANF Cash Help,” available at https://www.hhs.texas.gov/services/financial/cash/tanf-cash-help (last accessed July 2025).

4. Elaine Maag and others, “The Return on Investing in Children” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2023), available at https://www.urban.org/research/publication/return-investing-children; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Research and Data Priorities for Improving Economic and Social Mobility: Proceedings of a Workshop (Washington: The National Academies Press, 2022), available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/26598/chapter/8#90.

5. “TANF Financial Data – FY 2023,” available at https://acf.gov/ofa/data/tanf-financial-data-fy-2023 (last accessed July 2025).

6. “TANF and MOE Spending and Transfers by Activity, FY 2023,” available at https://acf.gov/ofa/data/tanf-and-moe-spending-and-transfers-activity-fy-2023 (last accessed July 2025).

7. Elizabeth Ananat and others, “The Costs of Cutting Cash Assistance to Children and Families” (New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy, 2023), available at https://povertycenter.columbia.edu/publication/the-costs-of-cutting-tanf.

8. Congressional Research Service, “The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant: A Legislative History” (2025), available at https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44668.

9. Kathryn A. Larin, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Preliminary Observations on State Budget Decisions, Single Audit Findings, and Fraud Risks,” GAO-24-107798 (Washington: Government Accountability Office, 2024), available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-24-107798.pdf.

10. Ibid.

11. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) – Key Statistics and Research,” available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap/key-statistics-and-research (last accessed July 2025).

12. “TANF Caseload Data 2024,” available at https://acf.gov/ofa/data/tanf-caseload-data-2024 (last accessed July 2025).

13. Government Accountability Office, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: HHS Needs to Strengthen Oversight of Single Audit Findings,” GAO-25-107291 (2025), available at https://files.gao.gov/reports/GAO-25-107291/index.html.

14. “Ronald Reagan Campaign Speech, January 1976,” available at https://soundcloud.com/slate-articles/ronald-reagan-campaign-speech (last accessed July 2025).

15. Ife Floyd and others, “TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance” (Washington: Center of Budget and Policy Priorities, 2021), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance.

16. Congressional Research Service, “The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant: A Legislative History.”

17. Justin Falk and Julia Heinzel, “Work Requirements and Work Supports for Recipients of Means-Tested Benefits” (Washington: Congressional Budget Office, 2022), available at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58199#_idTextAnchor008.

18. Gabrielle Pepin, “The effects of welfare time limits on access to financial resources: Evidence from the 2010s,” Southern Economic Journal 88 (4) (2022): 1343–1372, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/soej.12565.

19. Congressional Research Service, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF): Size of the Population Eligible for and Receiving Cash Assistance” (2025), available at https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44724.

20. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families” (2022), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/policy-basics-an-introduction-to-tanf.

21. Falk and Heinzel, “Work Requirements and Work Supports for Recipients of Means-Tested Benefits.”

22. Liz Schott, Ladonna Pavetti, and Ife Finch, “How States Have Spent Federal and State Funds Under the TANF Block Grant” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2012), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/how-states-have-spent-federal-and-state-funds-under-the-tanf-block-grant; “Poverty Guidelines,” available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines (last accessed July 2025).

23. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “22nd Welfare Indicators and Risk Factors Report to Congress.”

24. “2025 Poverty Guidelines: 48 Contiguous States (all states except Alaska and Hawaii),” available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/dd73d4f00d8a819d10b2fdb70d254f7b/detailed-guidelines-2025.pdf (last accessed July 2025).

25. “Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients, Fiscal Year 2023,” available at https://acf.gov/ofa/data/characteristics-and-financial-circumstances-tanf-recipients-fiscal-year-2023 (last accessed July 2025).

26. Olivia Golden and Amelia Hawkins, “TANF Child-Only Cases” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2012), available at https://acf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/child_only_0.pdf.

27. “Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients, Fiscal Year 2023”; Falk and Heinzel, “Work Requirements and Work Supports for Recipients of Means-Tested Benefits.”

28. Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 US 254 (1970), available at www.oyez.org/cases/1969/62.

29. “Social Security Act (1935),” available at https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/social-security-act (last accessed July 2025); James P. Ziliak, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.” Working Paper 21038 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w21038.

30. Code of Federal Regulations, “What does the term ‘assistance’ mean?” Title 45, Sec. 260.31 (2025), available at https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-45/subtitle-B/chapter-II/part-260/subpart-A/section-260.31.

31. “About TANF,” available at https://acf.gov/ofa/programs/tanf/about (last accessed July 2025).

32. Larin, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Preliminary Observations on State Budget Decisions, Single Audit Findings, and Fraud Risks”; Office of Community Services, “Social Services Block Grant (SSBG) Fact Sheet” (n.d.), available at https://ocsannualreport.acf.hhs.gov/annual-report-fy23/ssbg-fact-sheet.

33. Larin, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Preliminary Observations on State Budget Decisions, Single Audit Findings, and Fraud Risks.”

34. Josep M. Nadal-Fernandez, Gabrielle Pepin, and Kane Schrader, “Strengthening work requirements? Forecasting impacts of reforming cash assistance rules,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 44 (2) (2025): 663–673, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pam.22668.

35. “Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) – Overview,” available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/aid-families-dependent-children-afdc-temporary-assistance-needy-families-tanf-overview (last accessed July 2025); Congressional Research Service, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant: A Primer” (2025), available at https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48413.

36. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “2025 Budget Stakes: Vulnerable People Could Be Targeted for Painful Cuts” (2025), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/2025-budget-stakes-vulnerable-people-could-be-targeted-for-painful-cuts.

37. Congressional Research Service, “The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant: Responses to Frequently Asked Questions” (2024), available at https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32760.pdf.

38. Elizabeth Lower-Basch and Ashley Burnside, “TANF 101: Block Grant” (Washington: Center for Law and Social Policy, 2025), available at https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/tanf-101-block-grant/.

39. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Research and Data Priorities for Improving Economic and Social Mobility: Proceedings of a Workshop; Michael D. Tanner, “Twenty Years after Welfare Reform: the Welfare System Remains in Place” (Washington: Cato Institute, 2016), available at https://www.cato.org/commentary/twenty-years-after-welfare-reform-welfare-system-remains-place.

40. “RxKids,” available at https://rxkids.org/ (last accessed July 2025); Michael Hiltzik, “Stockton study shows that universal basic income can be life-changing,” The Los Angeles Times, March 6, 2021, available at https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2021-03-06/stockton-study-universal-basic-income; Sophie Collyer, Bradley Hardy, and Christopher Wimer, “The antipoverty effects of the expanded Child Tax Credit across states: Where were the historic reductions felt?” (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2023), available at https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-antipoverty-effects-of-the-expanded-child-tax-credit-across-states-where-were-the-historic-reductions-felt/.

41. U.S. Census Bureau, “Poverty in the United States: 2021-Current Population Reports” (2022), available at https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2022/demo/p60-277.html.

42. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Record Rise in Poverty Highlights Importance of Child Tax Credit; Health Coverage Marks a High Point Before Pandemic Safeguards Ended,” Press release, September 12, 2023, available at https://www.cbpp.org/press/statements/record-rise-in-poverty-highlights-importance-of-child-tax-credit-health-coverage.

43. Hilary W. Hoynes and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, “Safety Net Investments in Children.” Working Paper 24594 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w24594.

44. Marianne Bitler and Hilary Hoynes, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same? The Safety Net and Poverty in the Great Recession.” Working Paper 19449 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2013), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w19449.

45. Diana Azevedo-McCaffrey and Tonanziht Aguas, “Continued Increases in TANF Benefit Levels Are Critical to Helping Families Meet Their Needs and Thrive” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2025), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/continued-increases-in-tanf-benefit-levels-are-critical-to-helping.

46. California Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Trends in CalWORKs: Participant Characteristics” (2025), available at https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/5057.

47. “Poverty Thresholds,” available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html (last accessed July 2025).

48. “TANF Caseload Data 2024.”

49. Ibid.

50. “Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients, Fiscal Year 2023.”

51. Annie E. Casey Foundation, “California Kids: Data on Growing up in the Golden State” (2018), available at https://www.aecf.org/blog/california-kids-data-on-growing-up-in-the-golden-state.

52. Heather Hahn and others, “Why Does Cash Welfare Depend on Where You Live?” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2017), available at https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/90761/tanf_cash_welfare_final2_1.pdf; Joe Soss and others, “Welfare policy choices in the states: Does the hard line follow the color line?” (Madison, WI: Institute for Research on Poverty, 2003), available at https://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/focus/pdfs/foc231b.pdf.

53. Aditi Shrivastava and Gina Azito Thompson, “TANF Cash Assistance Should Reach Millions More Families to Lessen Hardship” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2022), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-cash-assistance-should-reach-millions-more-families-to-lessen.

54. “Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients, Fiscal Year 2023.”

55. U.S. Census Bureau, “Nearly Half of Renter Households Are Cost-Burdened, Proportions Differ by Race,” Press release, September 12, 2024, available at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2024/renter-households-cost-burdened-race.html; “Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients, Fiscal Year 2023.”

56. Ali Zane, Cindy Reyes, and LaDonna Pavetti, “TANF Can Be a Critical Tool to Address Family Housing Instability and Homelessness” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2022), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-can-be-a-critical-tool-to-address-family-housing-instability-and.

57. Veronica Gaitán, “How Housing Instability Affects Children” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2025), available at https://housingmatters.urban.org/articles/how-housing-instability-affects-children; Zachary Parolin, “Income Support Policies and the Rise of Student and Family Homelessness,” Annals of the Americans Academy of Political and Social Science 693 (1) (2021): 46–63, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0002716220981847.

58. Congressional Record, daily ed., August 1, 1996, p. S9387, available at https://www.congress.gov/congressional-record/volume-142/issue-116/senate-section/article/S9387-1.

59. “Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients, Fiscal Year 2023.”

60. Lauren Bauer, Sara Estep, and Winnie Yee, “Time waited for no mom in 2020” (Washington: The Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution, 2021), available at https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/paper/time-waited-for-no-mom-in-2020/.

61. Falk and Heinzel, “Work Requirements and Work Supports for Recipients of Means-Tested Benefits.”

62. “Minimum Wage,” available at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage (last accessed August 2025)

63. Sebastian Martinez Hickey and Ismael Cid-Martinez, “The federal minimum wage is officially a poverty wage in 2025” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2025), available at https://www.epi.org/blog/the-federal-minimum-wage-is-officially-a-poverty-wage-in-2025/.

64. Ife Finch Floyd and Suzanne Wikle, “Work Requirements Are Rooted in the History of Slavery,” Nonprofit Quarterly, February 29, 2024, available at https://nonprofitquarterly.org/work-requirements-are-rooted-in-the-history-of-slavery/; Teon Hayes and Akeisha Latch, “Rooted in Racism: The Origins of Work Requirements in Public Benefits” (Washington: Center for Law and Social Policy, 2025), available at https://www.clasp.org/blog/the-racist-roots-of-work-requirements-in-public-benefits-programs/; Ife Floyd and others, “TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2021), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance; Elisa Minoff, “The Racist Roots of Work Requirements” (Washington: Center for the Study of Social Policy, 2020), available at https://cssp.org/resource/racist-roots-of-work-requirements/.

65. Christian E. Weller, “African Americans Face Systematic Obstacles to Getting Good Jobs” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/african-americans-face-systematic-obstacles-getting-good-jobs/.

66. Ali Safawi and LaDonna Pavetti, “Most Parents Leaving TANF Work, But in Low-Paying, Unstable Jobs, Recent Studies Find” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2020), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/most-parents-leaving-tanf-work-but-in-low-paying-unstable-jobs.

67. Carolyn Bourdeaux and Lakshmi Pandey, “Report on the Outcomes and Characteristics of TANF Leavers” (Atlanta, GA: The Center for State and Local Finance, 2017), available at https://cslf.gsu.edu/download/outcomes-and-characteristics-of-tanf-leavers/.

68. Chantel Boyens and others, “Why a Universal Asset Limit for Public Assistance Programs Would Benefit Both Participants and the Government” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2024), available at https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/why-universal-asset-limit-public-assistance-programs-would-benefit-both-participants-and-government.

69. Ashley Burnside and Jesse Fairbanks, “Eliminating Asset Limits: Creating Savings for Families and State Governments” (Washington: Center for Law and Social Policy, 2023), available at https://www.clasp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/2023_Eliminating-Asset-Limits-Creating-Savings-for-Families-and-State-Governments.pdf.

70. Nadal-Fernandez, Pepin, and Schrader, “Strengthening work requirements? Forecasting impacts of reforming cash assistance rules.”

71. Heather Hahn, David Kassabian, and Sheila Zedlewski, “TANF Work Requirements and State Strategies to Fulfill Them” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2012), available at https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/25376/412563-TANF-Work-Requirements-and-State-Strategies-to-Fulfill-Them.PDF.

72. Jason B. Cook and Chloe N. East, “The Disenrollment and Labor Supply Effects of SNAP Work Requirements.” Working Paper 32441 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2025), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w32441.

73. Christopher J. O’Leary, Dallas Oberlee, and Gabrielle Pepin, “Nudges to increase completion of welfare applications: Experimental evidence from Michigan,” Journal of Behavioral Public Administration 4 (2) (2021): 1–8, available at https://journal-bpa.org/index.php/jbpa/article/view/237/118.

74. Tazra Mitchell, LaDonna Pavetti, and Yixuan Huang, “Life After TANF in Kansas: For Most, Unsteady Work and Earnings Below Half the Poverty Line” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/life-after-tanf-in-kansas-for-most-unsteady-work-and-earnings-below-half-the-poverty-line.