What the minimum wage can tell us about the future of the U.S. child care system

The U.S. child care market is plagued by a math problem. Families in the United States are stretched thin, dedicating substantial portions of their household budgets to child care expenses. Yet many child care workers find themselves among the lowest earners in the U.S. labor market. And all the while, child care providers are often barely keeping their heads above water with a meager 1 percent profit margin.

How can a service cost so much without its workforce making much money? Simply put, the answer comes down to liquidity constraints faced by both parents and providers, as well as high labor costs.

Families typically incur child care costs at a moment in their working lives when their general living expenses are high but their cash flow, or liquidity, is low. This liquidity constraint limits how parents can tolerate an increase in the cost of child care before turning to other options, such as a family member or reducing their own work hours. Providers are therefore discouraged from raising their prices—and, in turn, wages and profits—too quickly.

This creates a matching liquidity constraint for those child care providers who lack the profit margins to absorb any increases in business costs without a price pass-through to families. Since labor costs—workers’ salaries and benefits—account for between 65 percent and 76 percent of child care providers’ total expenses, they have to squeeze labor costs as low as possible to keep prices tolerable to their customers.

For decades, this liquidity tug-of-war yielded low, stagnant wages in the U.S. child care market. Since the COVID-19 pandemic and recession, however, circumstances exogenous to the child care sector have upended the standard formula.

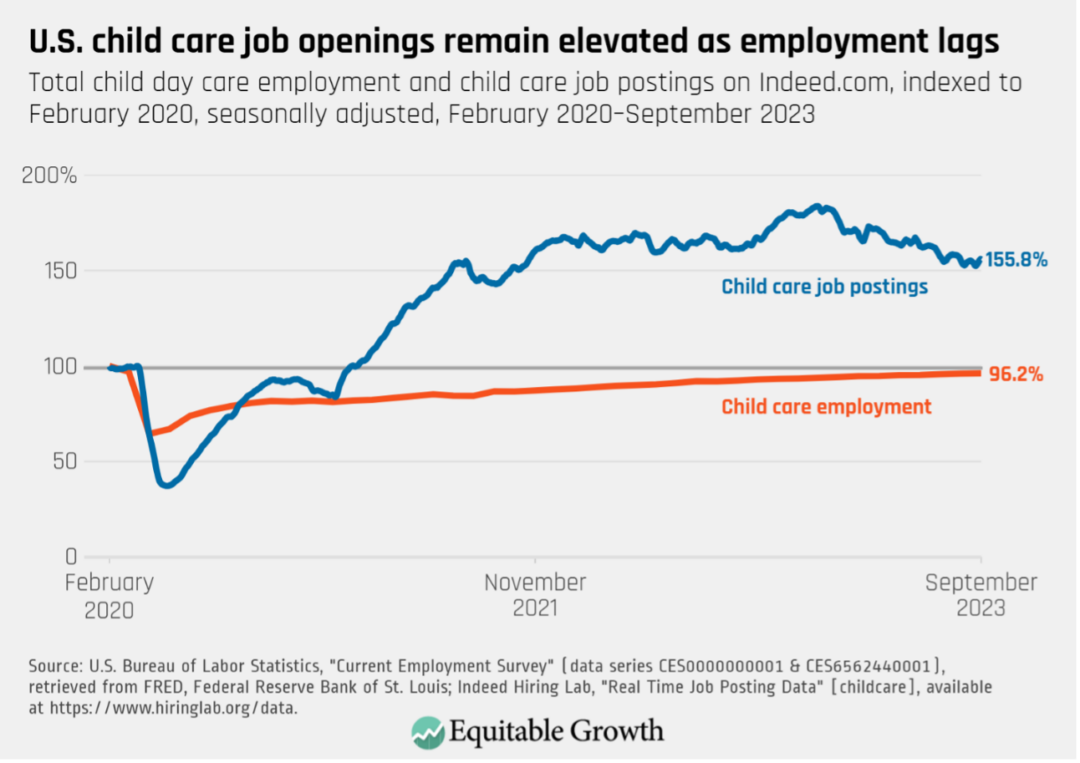

Tightness in the broader U.S. labor market—economic parlance for the excess demand for labor in the economy—resulted in rising wages across the economy. This trend put pressure on child care providers to offer better pay to attract workers back to a child care workforce that is still depressed relative to its pre-pandemic levels. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

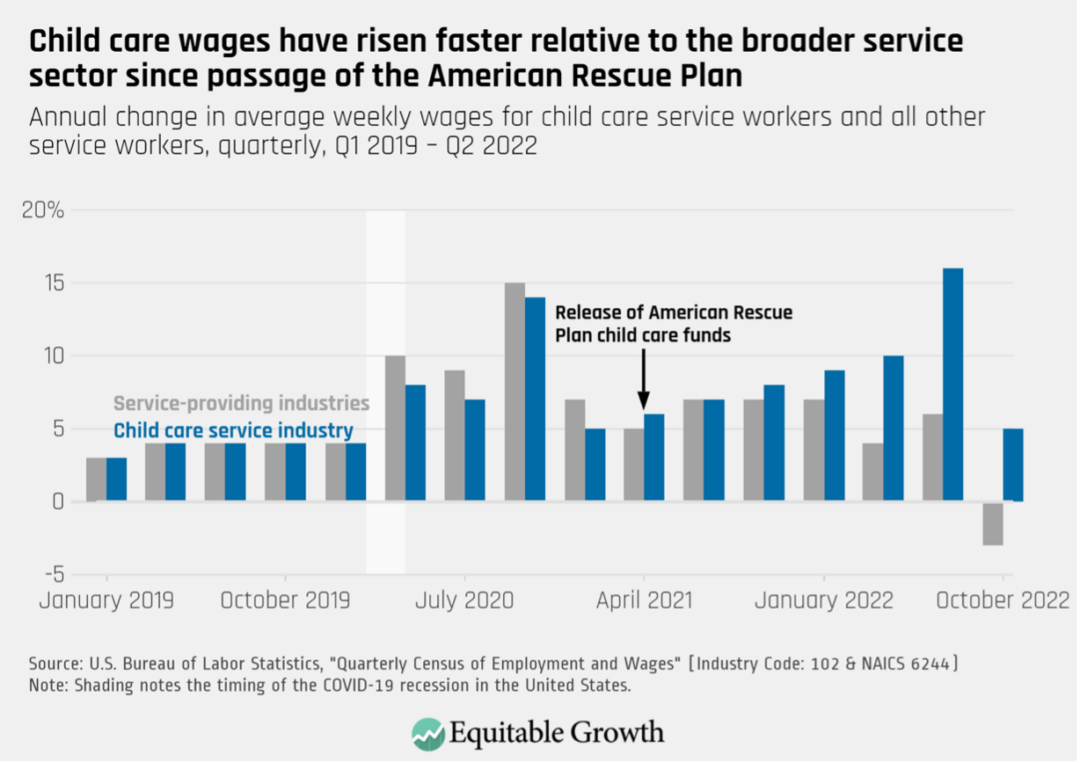

Additionally, in April 2021, the American Rescue Plan injected $39 billion in flexible funding into the child care sector. Providers could use these funds to pay workers’ bonuses or offer raises and higher pay, among other uses, likely alleviating providers’ liquidity constraints in the short term. More research is needed to identify the causal impact the law could have had on the child care sector, but early evidence suggests child care workers experienced accelerating wage increases since the American Rescue Plan funds were released. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The pandemic-induced labor market tightness and the infusion of cash in child care providers’ bank accounts helped facilitate wage increases for child care workers when normal business conditions would not otherwise have done so. Yet despite these recent wage gains for child care workers, the sector may soon return to its pre-pandemic status quo.

The U.S. labor market cooled in the latter half of 2023, reducing the pressure on providers to offer competitive wages. Additionally, a portion of the American Rescue Plan funds have already expired, leaving less money to shore up providers’ books. As such, providers, workers, and parents now face new uncertainties. Will wage gains be rolled back, further straining the already-reduced care workforce? If wages gains are sustained, what will that mean for providers’ business practices and their prices?

The answers to these questions—and thus insight into the future of the U.S. child care system—may lie in a useful analogy: the minimum wage.

Minimum wage changes demonstrate how providers respond to higher labor costs

Changes to the minimum wage typically facilitate pay increases when normal business conditions fail to generate adequate wages. Likewise, child care providers emerging into a post-pandemic world—where the market rate for child care labor has increased and they are now without the cushion of emergency federal funds—face a shock to their labor costs. They therefore may behave similarly to child care providers navigating changes to their business models in the wake of minimum wage increases.

How child care providers respond to changes in the minimum wage is the subject of a recent working paper by economists Jessica H. Brown at the University of South Carolina and Chris M. Herbst at Arizona State University. The authors combine two decades of minimum wage data from the Quarterly Workforce Indicators, market-rate price surveys used to set child care subsidy levels, and Child Care Development Fund data on subsidy receipt and use. Data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey and market research data allow for insights into the parameters of child care quality, while consumer reviews from Yelp allow the authors to understand parents’ satisfaction with their child care providers.

This comprehensive review of the minimum wage and the U.S. child care market yields largely positive news for child care workers. Their pay rose 1.2 percent to 2.3 percent for every 10 percent increase in the minimum wage, with no discernable impact on employment levels, consistent with other sectors. Care quality also improved, with staff turnover decreasing by 1.1 percent and workers making more human capital investments, such as taking courses and earning certifications in early childhood education. Additionally, child care workers had more high-quality interactions with children, as indicated by a 2.4 percent improvement on the Arnett Caregiver Interaction Scale, following a 10 percent minimum wage hike.

As expected from child care’s labor-intensive business model, the higher labor costs resulted in higher prices for families, with center-based market prices increasing between 4.2 percent and 8.1 percent following a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage. This price pass-through was higher than in other businesses affected by the minimum wage, such as fast-food restaurants, where labor costs are a smaller portion of overall business costs. Perhaps due to these price increases, parents’ reviews on Yelp decreased by 0.03 on a 5-point scale for every 10 percent increase in the minimum wage, suggesting that parents saw slightly less bang-for-their-buck under new pricing schemes.

In addition to price increases, child care providers adjusted their class sizes and composition to account for increased labor costs. Center-based programs saw enrollment increase by 5.6 percent and child-to-staff ratios rise 4.7 percent. Centers also accepted 12.2 percent fewer subsidized children, whose subsidies reimburse providers at a lower rate than what they charge unsubsidized families. Home-based providers, in turn, accepted more subsidized students, increasing subsidized enrollment by nearly 28 percent.

Child care providers responses to increasing labor costs after adjustments to the minimum wage offer insight into what might be expected in the months and years following the COVID-19 pandemic and the expiration of the American Rescue Plan child care funds. In the worst-case scenario, providers will respond to these higher costs with layoffs and even closures, eliminating child care slots.

Even if significant layoffs and lost child care slots do not ultimately materialize, providers may still respond to these increased costs by raising prices, adjusting class sizes, and shifting their composition of subsidized and unsubsidized students. In either outcome, child care would become less accessible and affordable for the families who need it most.

Public investment can mitigate unintended consequences while sustaining care workers’ wages

Policymakers have tools at their disposal to minimize these unintended consequences while preserving higher pay for child care workers in the United States. Supply-side grants, similar to the American Rescue Plan, or the emergency supplemental child care funding recently proposed by the White House, can ease providers’ liquidity constraints and reduce the price pass-through of higher labor costs. On the demand side, higher and more streamlined reimbursements for subsidized care—a change currently being contemplated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services—would help ensure that subsidized families can access the child care of their choosing.

Higher wages for child care workers are essential for the long-term health of the sector—which has long been plagued by turnover issues and staffing challenges—and consequently essential for the health of the overall U.S. economy. Without affordable and accessible high-quality child care, parents cannot be their full productive selves at work, and some may even exit the labor force if left without viable child care options.

Still, parents’ and providers’ dueling liquidity constraints provide few outlets for higher labor costs beyond rising prices and shifting classroom compositions. With or without higher worker wages, child care costs in the United States will continue to rise. Only robust public investment that treats child care as a public good—akin to the Kindergarten through 12th grade public education system—can sustain workers’ wages and ease providers’ liquidity constraints, all while shielding families from these rising costs.