What monetary and fiscal policy can tell us about the U.S. recovery from the COVID-19 recession

The Federal Reserve is at the center of the main story in the U.S. economy, and not just because there’s actual ambiguity around this week’s Federal Open Market Committee meeting. With inflation having moderated considerably, rising just 0.1 percent in May, interest rates are very much a drag on the economy due to the Fed’s aggressive pursuit of price stability over the past year.

This is not surprising. The Fed did what its playbook said it should do—delay rate hikes until it could hike aggressively. U.S. policymakers have added fiscal contraction to delayed monetary policy effects amid headwinds that will continue to build this quarter, but avoiding a debt ceiling catastrophe, a remarkably strong jobs market, and healthy consumer demand are keeping the U.S. economy growing even as growth abroad slows.

The central challenge for the Fed, and policymakers more generally, is how fast to bring inflation down and which tools can achieve the goal of stable prices soonest while balancing the Fed’s maximum employment mandate. Here are some of the factors in play.

Aggregate inflation is moderating, but counterintuitive dynamics abound

June’s FOMC meeting is likely to be the first without a rate hike in more than a year, but the effects of monetary policy notoriously take time to fully work through the economy. Financial conditions are likely to continue tightening for months even as the Fed backs off. An invaluable resource for gauging Fed policy returned this quarter with the New York Fed resuming publication of real-time estimates of the neutral fed funds rate, or r*—the interest rate that would balance today’s economy at the Fed’s employment and inflation targets, for the first time since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Among the most important long-term unresolved questions in macroeconomics is whether the persistent trend in low interest rates the U.S. economy has experienced since the 1990s is showing significant signs of reversing. The rapid recovery from the COVID-19 recession coupled with inflation and higher interest rates from the Fed have led to some speculation that these rates have moved, which would indicate the higher interest rates prevailing in the U.S. economy today are likely to persist. The return of these more rigorous methods confirms that the Fed could cut rates significantly and still slow the economy through reduced demand.

This time is different for monetary policy

Unlike in previous Fed rate-hiking cycles, underinvestment on the supply-side presents price pressures today and risks of higher future inflation if tightening policy too aggressively further weakens future supply. This is especially clear in interest-sensitive sectors such as housing and automobiles.

For instance, after a lost decade of housing construction, 15 years of 30-year fixed mortgage rates frequently under 4 percent, and a refinancing boom at the depths of the pandemic mean more than a quarter of mortgage rates are at 3 percent or less, and only a quarter are higher than 4 percent. This suggests that most homeowners with a mortgage would face very high switching costs if they moved today. Usually a typical rate-hike cycle would reduce housing demand more than it would slow residential construction to lower prices, but in this cycle higher rates are also depressing both the supply of new construction and the supply of housing that would substitute for new construction, creating unpredictable dynamics in housing inflation.

Auto sales have a different, albeit similar story, especially as demand rapidly increases for electric vehicles. The Covid-19 pandemic brought new attention to the auto sector, as supply disruptions drove extreme price volatility. While price volatility, especially for new vehicles, is new, the interest rate sensitivity of auto purchases, as well as the outsized effect of auto sales on the U.S. economy, are not. Vehicle sales make up a large share of consumer spending, while the number of parts in each car mean an even larger fraction of jobs are linked to automotive production.

Higher interest rates decrease the affordability of new and used cars, the vast majority of which are financed, yet the average amount financed remains well above pre-pandemic levels today. The pandemic supply disruption, however, came after a decade of austerity in the auto industry, a time when U.S households bought fewer new cars for most of the 2010s, the average age of vehicles increased steadily, and consumers were squeezed by a soft recovery from the Great Recession of 2007–2009. Automakers responded by offering longer and longer loan terms.

In contrast, during the current economic recovery from the short but sharp COVID-19 recession, the pent-up demand in the aftermath of the previous decade made auto sales surprisingly resilient to higher rates so far.

Between the strength of the U.S. labor market—detailed below— and consumer spending, the second quarter of 2023 is already different from this point in recent recoveries. But the long shadow of the Great Recession is both driving the Fed’s choice of macroeconomic policy and changing how interest rate hikes affect the U.S. economy.

Both monetary and fiscal policy have been contractionary in 2023

The main inflation concerns are still centered around how fast inflation needs to come down, but the combined effect of rapid monetary tightening and fiscal policy have U.S. demand set to cool significantly in the second half of 2023. The optimal policy is for the Fed to maximize employment by letting inflation fall as slowly as possible without affecting expectations of future inflation. This is quite hard, and yet it seems to be working quite well—a day before the June FOMC meeting, market forecasts of 5-year-ahead inflation were identical to those forecasts a decade ago.

Fiscal policy was already contractionary as pandemic-related stimulus spending wound down in the first half of 2023. Moreover, further cuts as a result of the recent debt ceiling deal and the resumption of student loan payments provide more domestic contractionary pressure. Recent research highlighting the distributional impacts on macroeconomic variables such as consumption on many middle and higher-income households suggests the resumption of these payments is likely to reduce consumption substantially.

The U.S. labor market is driving the recovery

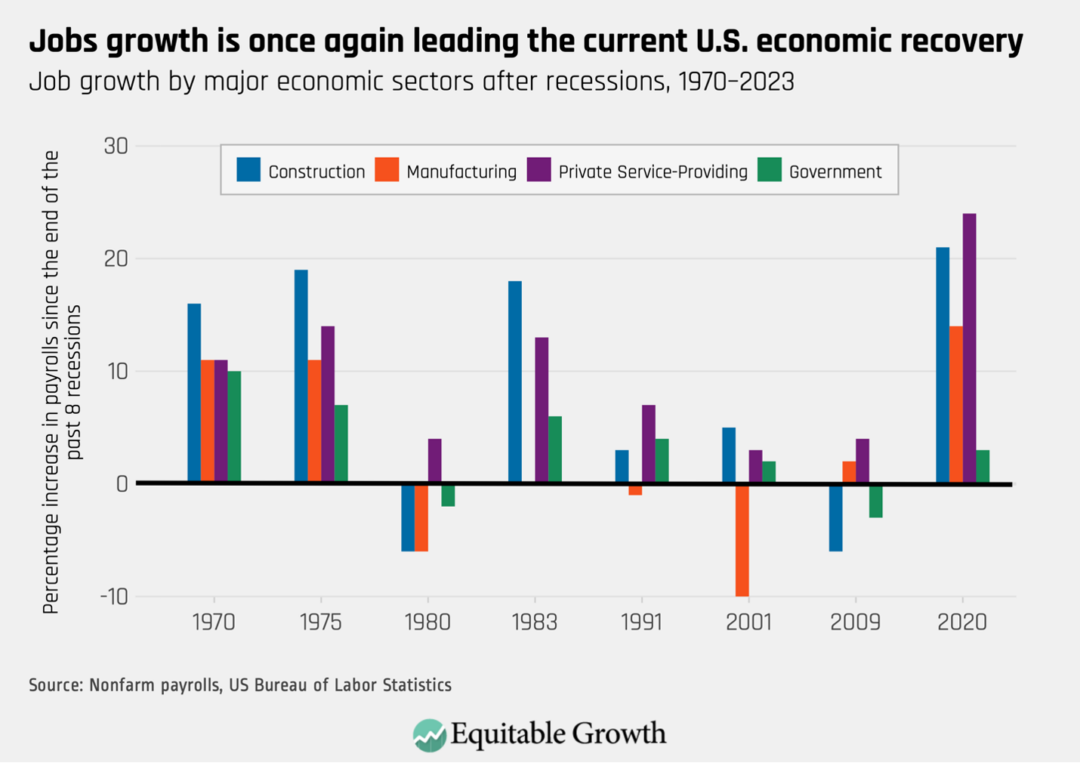

The shape of the current recovery is very different than the past few economic upturns. The U.S. labor market is leading the recovery. Goods consumption not only led GDP growth out of the recession, but also is having much stronger job recovery than any since the 1990s. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

In terms of larger macroeconomic phenomena, the upshot of strong jobs growth with slowing GDP growth is lower measured productivity. It’s still too soon to worry about precisely why productivity would be low right now given the number of disruptions in the economy and the mechanical effects of shocks to employment and output. Even still, declines in productivity in advanced economies are not unusual, underscoring the need for policy to focus on raising productivity.

The United Kingdom, for instance, is experienced a strong jobs recovery with very weak GDP growth following the Great Recession. The lack of productivity growth that resulted from these trends remains difficult to attribute to any specific factor, but after a decade there is little debate that it is a real phenomenon making life materially worse there.

Headwinds abroad

Much as it did immediately after the Covid-19 recession, the U.S. economy experienced many of the price and supply chain disruptions faced by other advanced economies, but grew more strongly, a pattern that appears to be continuing in 2023. The source of strength is the United States reaping the benefits it sowed with unusually strong household support during the depths of the pandemic. U.S. consumers have driven this recovery on the consumption side, and workers have driven the recovery on the production side.

U.S. policymakers must recognize, however, that the United States is not an island. Slowing growth abroad is all the more reason U.S. economic policy must prioritize maximum employment, especially as inflation ebbs.