Why measuring inflation is surprisingly challenging

In spite of recent bank turmoil in the United States and abroad, reining in inflation remains very much at the top of the macroeconomic agenda for policymakers in advanced economies in the first half of 2023. In the United States, the Federal Reserve is especially focused on its price-stability mandate, certainly ahead of its maximum-employment mandate, and potentially in the face of financial instability.

The Fed’s attention to price stability raises typically arcane questions about how changes in prices are measured, as well as more direct questions related to policy. Measuring inflation imposes several challenges under ordinary circumstances. But the unusual nature of the COVID-19 recession in 2020 and subsequently strong economic recovery reveals even more challenges as researchers and policymakers at the Fed work to identify causes of inflation to date, forecast future inflation, and learn how the two are linked. Critically, controlling future inflation requires understanding how people form expectations about future prices, a process that is much messier than assumptions built into many macroeconomic models.

With inflation declining from peaks in mid 2022, these tradeoffs in measuring inflation are an important policy focus in 2023 and beyond, especially as the Fed moves toward more moderate interest rate hikes, and as economic policy more broadly adapts to temporary and structural shifts set in motion since 2020. Newer research into how inflationary expectations are formed, as well as changes in how workers operate in the U.S. labor market, suggest that gains from a focus beyond traditional inflation gauges, such as the Consumer Price Index and the Personal Consumption Expenditure metric, both of which are workhorse inflation gauges for policymakers and the public.

In particular, the rise in remote work over the past three years is blurring lines between expenditures by consumers and firms, and presents a singular challenge to the efficacy of many existing inflation measures. In this column, I will present key benefits and drawbacks of both traditional measures of inflation and other measures that capture better the changing face of inflation in the U.S. economy since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Understanding what certain measures do and do not suggest, and which measures line up with which policy goals, is critical for policymakers and researchers as they face the challenges of dealing with today’s economy.

Measuring inflation is hard, and the pandemic made it harder

The concept of inflation is intuitively simple, but measuring inflation in practice is challenging on both a practical and theoretical level. Unlike many microeconomic measures, where revealed preferences allow for straightforward observations, inflation conceptually requires more than just a snapshot of observable behavior. If the price of bread increases so much that nobody buys bread at that price, for example, then how should this be reflected in official statistics? Other challenges are less philosophical but no less trivial, which is one reason there are many different inflation measures.

The ways that consumers change their purchasing patterns as prices change, or what is referred to as substitution, is a crucial question for inflation measurement with multiple valid answers. The two most used inflation gauges, the CPI and PCE measures, are constructed using much of the same data, but notoriously differ due to scope, weighting, and formula effects—in part reflecting differing approaches to modeling substitution patterns.

Before adopting a specific measure of inflation, it’s crucial to first consider what the information will be used for. For instance, core measures of inflation exist to remove volatility from food and energy prices that can create noise in inflation readings. But there is a tradeoff—smoother readings can help U.S. policymakers focus on the durable trends policy can affect, but can conceal the strains that workers feel from rising food and energy prices. One case in point: while policymakers might focus on core inflation to guide future economic policy, Social Security benefits are indexed to all prices, because retirees can’t ignore food and energy prices.

The Fed’s stated goal of maintaining well-anchored inflationary expectations points to the importance of using a measure that affects these expectations, especially when different inflation measures diverge. When expectations are well-anchored, people and financial markets are confident that future inflation will be close to target in the long run, regardless of developments in the short run. Core consumer price indexes have been historically important for allowing policymakers to look through supply-side disruptions that policy can amplify rather than stabilize.

The introduction of inflation-protected U.S. government bonds in 1997 (the value of the bonds is indexed to CPI) generates market-based measures of CPI inflation expectations. While these can measure expectations over CPI inflation, it is much harder to show that those expectations are driven by CPI data or any specific price indexes. Indeed, empirical work finds consumers’ inflation expectations are quite sensitive to things such as gas prices, in tension with the hyper-rational expectations-setting behavior used in many macroeconomic models.

Consumer price and wage inflation measures face a number of challenges amid the current economic recovery

Consumer price-based inflation indexes, in contrast to producer price-based indexes, are still the standard, for a variety of reasons beyond simple consistency. First, consumption makes up more than half of U.S. Gross Domestic Product, and consumption is the least volatile component of GDP, so the two consumer price-based inflation measures, CPI and PCE, are more stable over time.

Typically, the Fed focuses on personal consumption expenditure inflation, which covers about 2/3rds of the U.S. economy and is less volatile than alternative measures. And past research suggests that wage pressures are driven by consumers’ price expectations, while in simple models with perfect competition consumer expectations are necessary to drive a wage-price spiral. Yet recent research on monopsony consistently demonstrates there is imperfect competition in the U.S. labor market.

Among certain policymakers at the Fed and researchers more broadly there is concern over wage inflation, rather than price inflation. In part because other inflation gauges have been more noisy amid the continuing economic recovery, a way to focus on whether wages are driving prices higher offers another measure of price stability—especially in service industries. Yet there are issues with these measures as well. High frequency measurements are problematic because they average wages across industries so ‘average earnings’ often reflect which industries are hiring and firing more than wage changes.

The quarterly Employment Cost Index compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics controls for hiring composition quite well. ECI wage growth has been robust in the current recovery, but has stabilized. And after decades of corporate profits growing to a much larger share of the U.S. economy—well above historic averages—there is significant room for wages to grow faster than prices in the medium term if the result is workers’ incomes return to historically normal shares of output.

Spending shifts or inflationary pressure

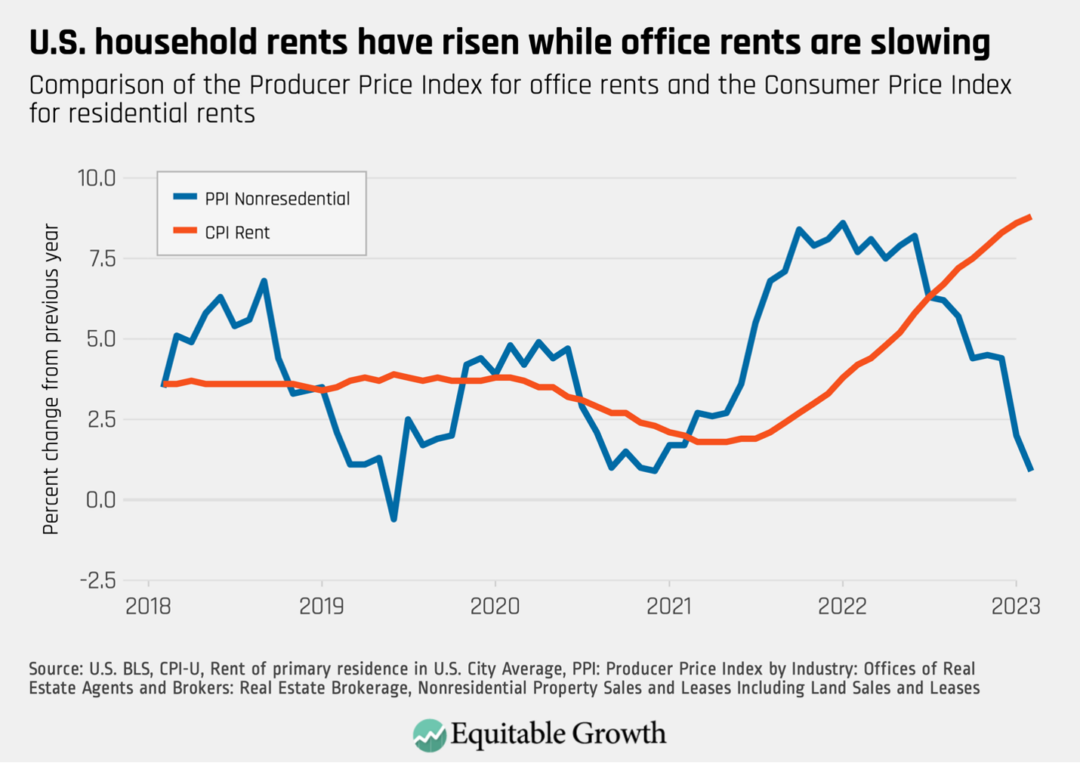

In today’s economy, measuring consumer inflation is confounded by how the pandemic reoriented the economy; many producer and consumer expenditures now blend. As researchers focus on the role that housing cost measurement plays in inflation, remote work complicates the use of consumer housing and rental inflation measures. Consumer rents have risen in part due to demand for home offices, but consumer prices show the effects of this increased demand while excluding offsetting declines that are weighing heavily on the commercial real estate sector. This unbalanced picture of price pressures can skew inflation measurements and perceptions of capacity constraints in an economy, presenting new challenges to well-established, standardized inflation taxonomy. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

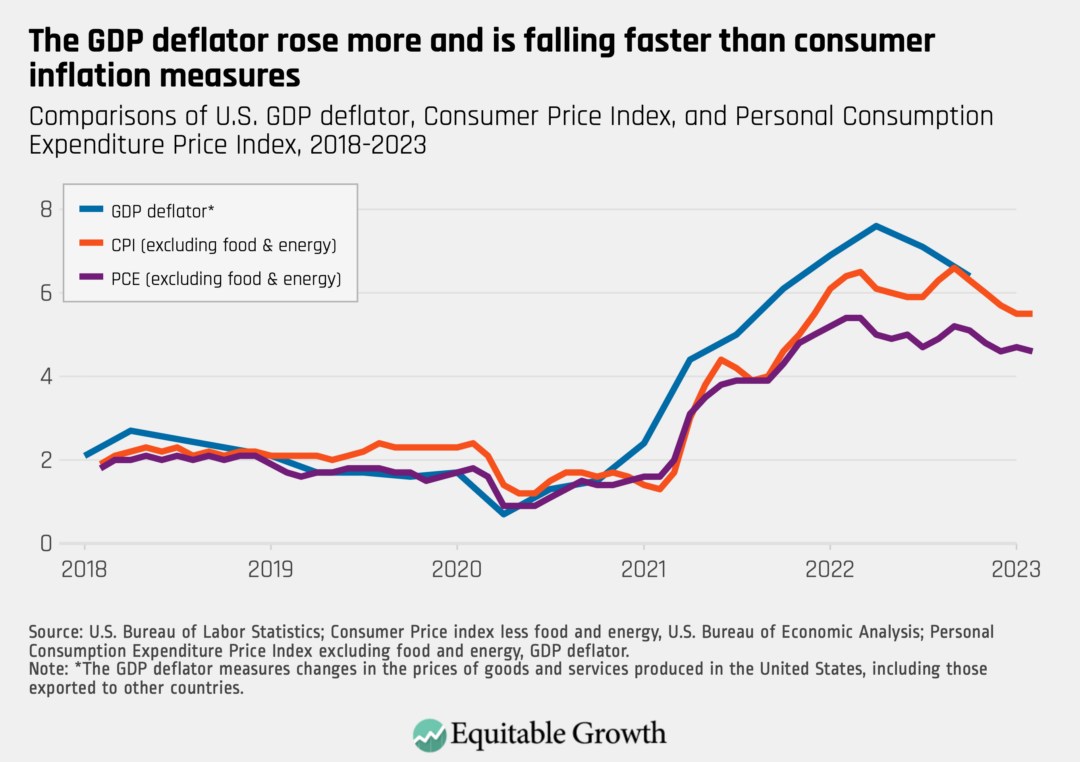

Beyond consumer measures, there are broader measures of price pressures that are less sensitive to classification and can better capture shifts like this. The GDP deflator and GDP price index are more inclusive of all sectors of domestic consumption, and alleviate some concerns with substitution across categories, though neither is perfect. Because these measures come out quarterly, they don’t provide policymakers with real-time information about the U.S. economy.

Similarly, they also are less likely to affect the inflationary expectations of consumers and firms because they are less widely covered by media outlets and the Federal Reserve. Because the GDP deflator includes firm prices that are more volatile, it shows higher inflation earlier in the pandemic, but it also has decelerated faster and farther than consumer measures. This economy-wide measure of inflation is more volatile, but also shows that demand outstripping supply may be less of a driver of current inflation than consumer prices suggest. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

To be sure, there are a number of reasons to focus on consumer prices—social security benefits, tax brackets, and TIPS bonds are all adjusted for inflation using various consumer price indexes. Consumer inflation expectations are extremely important for inflation expectations, especially in wage-setting activity between workers and firms. But this is not an ironclad relationship, with recent research suggesting that consumer price inflation may not be the most predictive measure of consumer inflation expectations. Gas prices have low predictive power over future inflation, for example, but play a very large role in consumer inflation expectations.

Measuring expected inflation

A key challenge in measuring inflation is that regardless of how policymakers track inflation, firms’ and households’ expectations of future inflation are arguably more significant for the economy. In fact, the level of inflation is far less consequential in economic models than the current debate might suggest, but expected inflation can be extremely important for real economic variables. Inflation expectations, factor into interest rates, pricing decisions, and a host of variables that affect the real economy.

Because these inflation expectations are a first-order concern, there can be reasons to focus on a particular price index if the measured inflation reported by that index is influential by itself. If households’ expectations are the main determinant of expected inflation, for example, then measures of consumer prices could offer a significant benefit if these prices, which consumers see in stores often, are unusually influential over households’ beliefs.

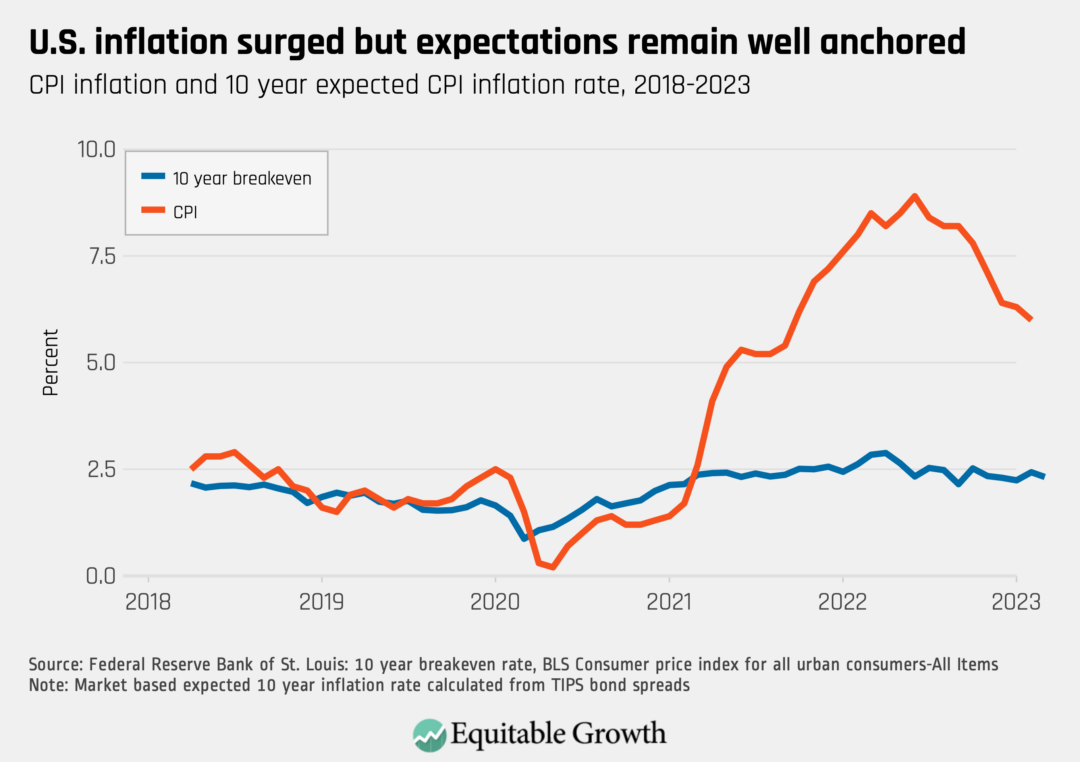

Economywide inflation expectations are not hypothetical and can be measured by comparing interest rates on standard government bonds with inflation-indexed bonds. Yet expected inflation has remained well-anchored through the post pandemic inflation surge, suggesting that the credible commitment by the Federal Reserve to return to its 2 percent target is more influential than medium-term movements in any particular price index. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Conclusion

More research is clearly needed to understand the best measures of inflation to inform macro models, especially as the U.S. economy continues to respond to structural changes. There is a need for both an accurate understanding of capacity constraints in the economy, and a consistent measure of changes in inflationary expectations—and these may not be well captured by any one measure, let alone the measures traditionally used. For U.S. policymakers, the challenge is twofold. They need to calm inflationary expectations on the one hand, even if expectations are not based on a full understanding of what may persistently drive future inflation, while also preserving the health of the economy itself on the other. Balancing these needs will also require reexamining old assumptions.

Measuring inflation is hard. Official statistics are very good at measuring inflation, but how to use those measures is more tricky because it is conceptually difficult and context dependent. The COVID pandemic makes the application of go-to inflation measures even more challenging as it created unprecedented shifts in spending across sectors, leading to shifts appearing as increases or decreases in major components of primary inflation measures.

An additional challenge: Whether these measurements are conceptually correct may not be the end of the story because expectations themselves matter so much for policymaking. Inflation expectations remain well-anchored even after 2 years of inflation levels well above the Fed’s target range of 2 percent, and amid sensational financial and economic reporting on every inflationary pressure in the U.S. economy.

Consumers’ outsized focus on gas prices, for example, suggests that the Biden administration’s use of the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve to manage gas prices and the subsequent decline in oil prices may be playing a role in broadly held expectations that inflation will moderate over the next few years. Other administrative actions or fiscal policy moves such as this also could help lower inflation expectations.

Inflation accelerated out of the pandemic, cooled significantly, then accelerated again as COVID variants emerged. The Fed was hamstrung by a decade of slow growth, but followed the research on monetary policy in a liquidity trap. Inflation has moderated considerably, but the inflation story going forward will require more careful attention to inflation measures, including some that don’t typically make news.