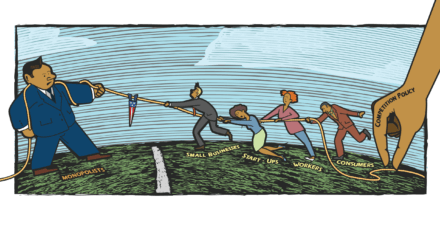

Fair competition in the U.S. labor market is threatened by more than the noncompete clauses targeted by new Federal Trade Commission rule

When a worker gets a new job, it is normally a cause for celebration and not litigation. Yet noncompetition clauses in employment agreements, and a veil of other threats buried in employer paperwork, weaken workers’ freedom to shop their skills in the U.S. labor market. To end unfair competition and boost the productivity of the U.S. economy, the Federal Trade Commission is currently asking the public to comment on a new rule that bans noncompete clauses that some firms force employees and independent contractors to sign as a condition of employment.

My latest research project illuminates a greater scope, prevalence, and variety of anticompetitive practices than has previously been described. “New Evidence on Employee Noncompete, No Poach, and No Hire Agreements in the Franchise Sector” reports the results of an analysis of 17,785 franchise disclosure documents and suggests that rulemaking and enforcement efforts might miss anticompetitive practices that currently lie in the shadows—buried in millions of pages of documents already in the public domain.

My paper raises the concern that research and policy seeking to address anticompetitive practices could be limited by the so-called streetlight effect, or focusing only on the problems that have already been exposed to the light. The FTC rule, for example, cites lawsuits and media reports that have, to date, been a main source of information. While these sources provide substantial evidence regarding noncompete clauses, other methods of unfair competition that are similar to noncompetes remain in the shadows.

There is still time to better describe practices that effectively are noncompete agreements covered by the FTC rule. The agency, on January 8, invited comments and indicated that no poach rings, no hire agreements, nondisclosure, trade secret, proprietary, and confidential information clauses can also be used to threaten and block workers from gaining a different job at a competing firm. More than 12,000 comments from members of the public have already been received, and additional comments are welcome until March 20.

This column details new methods used to pinpoint anticompetitive language in a massive document collection and illuminates some of the lesser-known clauses that can have the same effect as noncompetes.

Open-source machine learning and natural language processing tools can track noncompete clauses and other anticompetitive practices

The findings in my new research paper are the result of a years-long effort to acquire a massive collection of contracts that are already in the public domain and online but which are unable to be researched or analyzed due to inaccessible websites, unsearchable text document formats, unstable links, and a lack of clear software tools or methods to analyze a collection of documents. The evidence gathered includes more than 157,000 documents obtained from websites from the states of California and Minnesota, with a variety of technical challenges overcome along the way.

My paper uses and develops new natural language processing and machine learning methods to count and identify a variety of clauses. Graduate and undergraduate research assistants helped develop and validate “context rules” that are matched with the text. A machine learning model and knowledge tools that can automate the identification of new, unseen cases of anticompetitive conduct are now available as open-source replication materials.

The project initially began as a search for nonsolicitation, or no poach, clauses, but additional language in the franchise documents also carries anticompetitive implications. Based on exact matches with rules that define a no poach clause, 44 percent of franchise filings had a no poach clause from 2011–2022. In addition, 25 percent had a no hire clause that bars franchisees from hiring a worker at another franchise in the same franchise chain. Twenty-six percent had language that approves of or requires franchisees’ use of noncompete clauses.

Language found in the disclosure documents also reveals that despite aggressive enforcement efforts by the Washington state attorney general’s office, approximately 10 percent of disclosure documents in 2022 contained language that bars firms from soliciting or hiring another firm’s workers within the same franchise chain.

The ability to conduct this research is enabled by software called Context Rule Assisted Machine Learning. The open-source method enables researchers to find any concept in any document collection and was developed at Loyola University Chicago’s Quinlan School of Business. My paper compares results between hand-coded data, exact matching with rules, and a machine learning approach that identified a larger number of suspect clauses. A separate paper provides additional methodological details on the construction of the no poach machine learning classifier that can rapidly identify suspected clauses in documents, and is co-authored by me and Stephen Meisenbacher at the Technical University of Munich.

DocumentCloud/Muckrock, a nonprofit organization, now hosts the corpus collected in this research project on its website, where documents can be linked to, annotated, and searched. This research project also received generous support from the Economic Security Project’s Anti-Monopoly Fund, the Loyola Rule of Law Institute, the Loyola Quinlan School of Business, and Loyola University Chicago.

Many more barriers to job mobility exist than just noncompete clauses

With the documents now easy to link to and annotate, several examples illustrate the problems buried in the fine print. Despite aggressive enforcement since 2017, fast-food franchisor Sbarro Inc., in 2021, bars franchisees from soliciting or employing other franchisees’ workers. Previously unexamined interfirm noncompetition clauses involving franchisors requires franchisees to force their employees to sign noncompete agreements. In the same sentence, the franchisor Big Apple Bagels also requires franchisees to force employees to sign nondisclosure clauses.

In my paper, I caution against regulatory and scholarly focus on only the noncompetition clauses that are known about today. As one practice is blocked, new barriers for workers may emerge. As illustrated above, many ordinary U.S. workers are also required to sign documents of debatable legality that require them to maintain “absolute confidentiality” of “trade secrets” and “proprietary information.” Workers can even face dubious threats upon joining another firm if they have learned new skills and professional methods while on the job.

At Godfather’s Pizza chain restaurants, “information, processes, or techniques” that are generally not considered confidential information are nonetheless covered by nondisclosure agreements if workers learn the information on the job while working for a franchisee. Russo’s New York Pizzeria Restaurant chain requires franchisees to pay costs and expenses for hiring managers from other franchisees and requires management personnel receiving training to sign confidentiality covenants.

Restoring competition requires better anticompetitive enforcement

With the strongest U.S. labor market in decades, employers can retain workers either with better employment practices or through attempts to limit workers’ freedom to quit. As a stream of research by Evan Starr at the University of Maryland’s Smith School of Business and other work by Matthew S. Johnson at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, Kurt Lavetti at The Ohio State University, and Michael Lipsitz at the Federal Trade Commission shows, limiting the use of noncompetes and other anticompetitive practices is likely to increase workers’ opportunities in the labor market, boost wages, and increase the number of new firms in the market. When people and knowledge flow more freely and firms compete to attract and retain workers, then the overall U.S. economy can grow faster.

Restoring competition in the United States

November 19, 2020

An important 2020 report on competition by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth describes how the federal government can do much more to address growing market power. A whole-of-government approach to labor and antitrust serves the aims of ensuring U.S. workers have good labor market opportunities. The FTC rule is one prime example of this, but other efforts across the government could include using the federal government’s buying power to limit the use of anticompetitive practices.

At the state level, for example, all procurement contracts in Illinois bar firms from restricting employee mobility through noncompetition clauses and ban them from contracting with other firms to “prohibit said independent contractor, subcontractor, or employee from competing, directly or indirectly, in any way with the Vendor.” Such state rules, along with the new FTC rule, illustrate the potential for a wide range of government action to improve the competitiveness of labor markets and protect workers’ fundamental right to quit sand accept better opportunities.