October U.S. Jobs report: Employment growth picked up steam last month

Job gains in the U.S. labor market picked up in October, according to the latest Employment Situation Summary released today by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Between mid-September and mid-October a total of 531,000 jobs were added to U.S. economy as COVID-19 cases declined after surging in the late summer, compared with the 483,000 jobs added in August and the 312,000 jobs added in September. In addition, the agency made substantial revisions to its August and September employment estimates, increasing the 3-month average job gains to 442,000; without the revisions that average number would have been of just over 363,000 jobs.

A key measure for the labor market, the prime-age employment-to-population ratio, or the share of 25- to 54-year-olds who have a job, rose from 78 percent to 78. 3 percent. And the overall unemployment rate continued to fall, dropping from 4.8 percent in September to 4.6 percent in October. These indicators show that the U.S. economy is on its way to a robust jobs recovery, yet some metrics used to measure the detailed health of the labor market failed to make much progress.

The labor force participation rate, for example, continues to be well below its pre-coronavirus levels. At 61.6 percent, the share of U.S. adults who are either employed or actively looking for work stayed flat over the last month and remained at roughly the same level since June of 2020.

As of October, there are 3million fewer workers in the labor force than there were prior to the start of the coronavirus recession in February 2020. A still low labor force participation rate is particularly worrying because this indicator previously never returned to its pre-crisis levels in the aftermath of either the 2001 recession or the Great Recession of 2007–2009. The only sector to shed jobs in October—the public sector—lost more than 150,000 jobs over the past three months.

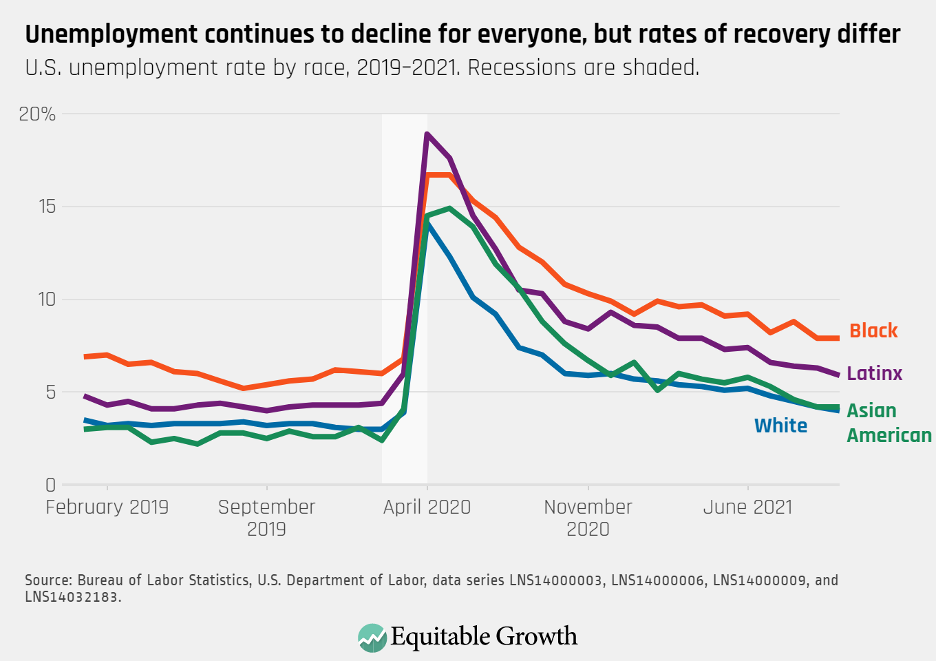

Across race and ethnicity, the unemployment rate continues to be highest for Black workers—the racial or ethnic group whose unemployment rate tends to be most sensitive to both economic contractions and expansions. At 7.9 percent, the jobless rate for Black workers remained unchanged between September and October, and is almost double the unemployment rate of White workers (4 percent). The jobless rate for Asian American workers also remained flat, staying at 4.2 percent. Latinx workers are currently experiencing a 5.9 percent jobless rate—2.9 percentage points above the unemployment rate for White workers. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

There also are large differences in employment and labor force participation by age group. A year after the onset of the coronavirus recession, for example, the youngest workers in the U.S. economy were faring better than their older counterparts. Workers between the ages of 16 and 19 experienced employment declines of only 4.4 percent between February 2020 and February 2021.

Conversely, the pandemic initially hit the oldest workers much harder than early- and mid-career workers, and over the same period adults 65-years-old and older experienced a massive 10 percent decline in employment. For instance, according to an analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data by the Urban Institute, the labor force participation rate for U.S adults ages 65 and older fell 11.1 percent between February 2020 and February 2021—the largest 12-month drop in 60 years.

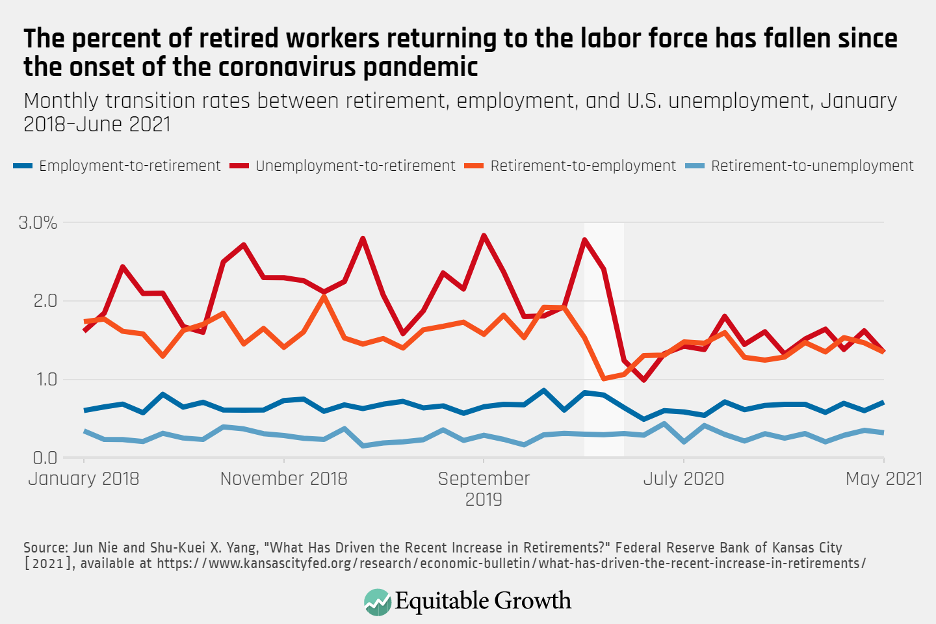

Alongside this drop in both employment and labor force participation, retirement rates increased dramatically amid the pandemic. According to a recent report from the Kansas City Federal Reserve, for example, the number of retirees increased by 3.6 million retirees between February 2020 and June 2021 or more than twice as many as would have been expected under previous trends.

The Kansas City Federal Reserve authors find that the overall increase is not driven by a greater number of retirements. Instead, they cite “a steep decline in the percentage of retirees returning to work” during this time, possibly due to health concerns for this higher-risk group during the pandemic. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

This shift may not reflect a permanent transition to retirement for all of these workers, however, as many may return to work as risks subside, particularly for those who are still young enough to return to the labor force. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Many older workers face important challenges in the U.S. labor market and barriers to a good retirement

Retirement trends are likely to normalize as the U.S. economy continues to recover, yet this spike in the number of retirees has put a spotlight on the challenges that older workers experience in the labor market. Hiring discrimination, for example, may make it more difficult for older workers to find new jobs after separations during the pandemic.

Indeed, a working paper by Gordon Dahl at the University of California, San Diego, and Matthew Knepper at the University of Georgia suggests that age discrimination charges in hiring and firing rose in the period of higher unemployment after the Great Recession. Examining data from a correspondence study using fictitious resumes of college-educated women with significant work experience, the authors also find that the callback rate for older women versus younger women fell by 15 percent for every percentage point increase in the local unemployment rate.

Other research finds that age discrimination in hiring appears to be more prevalent against older women than older men, and older women may be subject to a disproportionate amount of monopsony power compared to other workers. Age discrimination intersects with discrimination by race as well, with one study finding disproportionate hiring discrimination among Black applicants in the oldest and youngest age groups. In addition, the Urban Institute also found that older adults who are able to find new jobs after being unemployed during the Great Recession and recovery received lower wages.

There also are large inequities in retirement readiness by gender and race, with many female workers and workers of color having no retirement savings other than Social Security. White families are far more likely to have access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan, and more likely to participate in one, according to a Federal Reserve analysis of the Survey of Consumer Finances. The analysis finds that while 60 percent of White families participate in a retirement plan, the same is true for only 45 percent of Black families and 34 percent of Hispanic families. White families typically have much higher levels of household wealth overall compared with Black and Hispanic families, as the analysis notes, further contributing to disparities in retirement readiness.

Access to employer-sponsored retirement plans has fallen over time, and the types of plans workers participate in has shifted from defined-benefit plans, often called pensions, to 401(k) and other defined-savings accounts, which may not ensure adequate income in retirement. Overall, employer-sponsored retirement plan coverage declined less for workers in unions compared with other workers between 1999 and 2011, and workers in unions remain far more likely to participate in retirement plans than those who are not in unions, as the Economic Policy Institute notes.

Then there’s the need for older workers to be able to access to both good working conditions and a good retirement as the U.S. workforce ages. The pandemic pushed many U.S. workers into retirement, but longer trends reflect that both due to choice and necessity many older workers have been extending their careers over the past few decades. That many older workers are delaying or forgoing retirement could exacerbate other inequities, since older workers without a college degree are more likely to hold physically demanding jobs, and older workers with health problems are losing out on the financial benefits of a late retirement.

The trend toward later retirement can have other effects on the U.S. labor market, too. One is that it creates bottlenecks in career ladders that may affect the career progressions and wages for younger workers.

Conclusion

The latest Jobs report in October shows that more than 7.4 million workers who want a job and are actively looking for one did not have one, and the U.S. economy is still at a 4.2 million job deficit with respect to February 2020. These workers across the spectrum of age, gender, and race and ethnicity will return to the labor force most immediately when the pandemic is brought under more control so that those who want to return to work can do so without the fear of getting sick.

More broadly, as both the workforce and the population age, it will become increasingly important to invest in the country’s social infrastructure by ensuring that people can reach accessible and high-quality elder care, that the workers who care for the country’s older adults are fairly compensated and have good working conditions, and that the country’s families have access to robust Social Security benefits and disability benefits. It will also be important to effectively enforce labor laws that are meant to protect older adults from employment discrimination.

Empowering U.S. workers with the legal and institutional support they need to reach good labor market outcomes and be treated fairly at work—as well as to be able to have a good retirement if they choose to stop working or are unable to work—will be essential for broad-based and sustainable economic growth.