Uncertainty about the size of annual tax refunds hinders the effectiveness of tax-based U.S. redistribution

Each tax season, many families in the United States receive additional income through refundable tax credits, among them the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit. These two tax credits can comprise a significant portion of income for the 25 million and 48 million recipients of the EITC and CTC, respectively.

The average EITC recipient, for example, receives a tax refund equal to 12 percent of their annual income. These credits are delivered as one-time payments shortly after individuals file their taxes.

The recently enacted American Rescue Plan both increases the Child Tax Credit and expands eligibility for it as well as the Earned Income Tax Credit. Yet because the rules governing tax credits are often complex, it can be difficult for individuals to figure out how much money they will receive in their refunds. If tax filers do not know how much they will receive, they may then have trouble planning their finances throughout the year. Subjective uncertainty can be economically costly, dampening the overall value of these credits.

In our new working paper, we quantify the uncertainty about annual tax refunds and estimate the costs of subjective uncertainty for tax filers’ well-being. We find that uncertainty about the annual refund can erode a meaningful share of the value of these refunds for recipients, reducing the effectiveness of programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit.

Measuring beliefs about tax refunds

We conducted surveys at a Volunteer Income Tax Assistance site in Boston to gauge tax filers’ expectations and degrees of uncertainty about their upcoming tax refunds. Just before individuals filed their taxes, we asked about their “best guess” of the size of their refunds, how “certain” they were about the amount they thought they would receive, and what probabilities they would assign to their refunds falling within each of the six ranges: less than $0 (meaning they would not receive a refund or might have additional tax due); $0 to $500; $500 to $1,000; $1,000 to $2,500; $2,500 to $5,000; and more than $5,000. With respondents’ consent, we then linked the survey to tax data, a panel of filers’ credit reports, and a demographic survey.

By the time we interviewed tax filers, the 2015 tax year was already over, and filers had already earned their total incomes for that year. They also had already gathered all of their tax documents. Nevertheless, tax filers were uncertain about their tax refunds. A quarter of individuals told us they were “not at all certain” that their tax refunds would fall within $1,000 of their best guesses.

As another measure of this uncertainty, we analyzed individuals’ responses to the probabilistic survey questions using standard economic techniques. We find that individuals’ uncertainty about their refunds is 4.5 times larger than recent estimates of U.S. labor income uncertainty—for example, uncertainty related to whether they might lose their jobs.

The upshot: Filers’ uncertainty was “accurate.” The more uncertain individuals were, the worse they were at predicting what their refund would be. The gap between tax filers’ expected refund and the refund received was larger if they were more uncertain.

Who is the most uncertain?

When we compared tax filers’ beliefs with their actual refunds, we find some characteristics that predicted how uncertain a filer would be. Filers tended to be more uncertain if they had a dependent, had large changes in their incomes, or were young. These filers also faced greater tax complexity in the sense that their refunds and marginal tax rates had changed more relative to the prior year.

These patterns are consistent with uncertainty being the result of more complex parts of the tax code, such as the income-based phase-in and phase-out boundaries for the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit or rules for married filers.

Despite high levels of uncertainty, tax filers on average were able to accurately predict their tax refund amounts. This accuracy is not simply due to tax filers remembering what they received the previous year. Rather, we find that filers’ beliefs were strongly correlated with year-over-year changes in their refunds, suggesting that filers updated their refund expectations in response to new information over the year.

Does refund uncertainty matter?

In order to examine whether refund uncertainty affected the day-to-day lives of these tax filers, we used the linked credit report data to analyze the relationship between uncertainty and financial behavior. We find that more uncertain individuals tended to borrow less before receiving their tax refunds. This reduced credit utilization is likely due to these filers wanting to insure against the risk of receiving a lower-than-expected refund. In the language of economics, they engage in “precautionary behavior.”

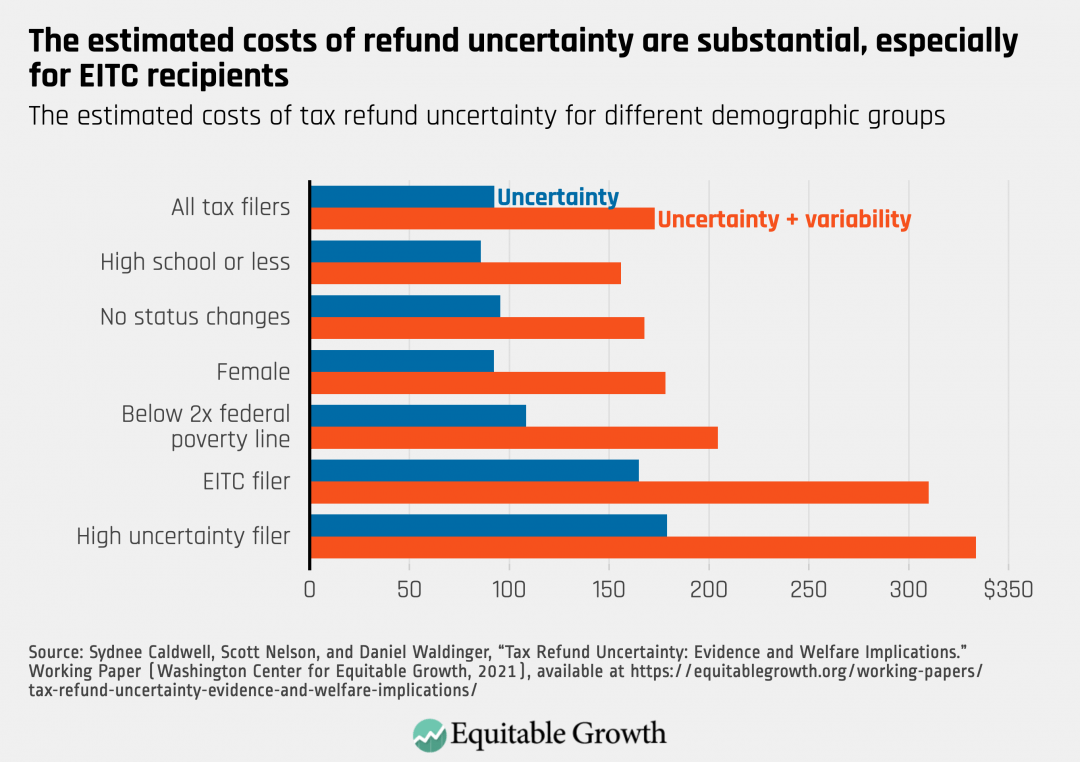

We then used a simple economic model of consumption, borrowing, and savings decisions to estimate how subjective uncertainty affected how much tax filers valued their refunds. The model suggests that the average filer would give up $93 per year to eliminate tax refund uncertainty, but the average EITC recipient would give up $165 per year. Given that the average EITC filers in our sample receive roughly $1,600 from the EITC alone, this implies that, on average, EITC recipient would give up almost 10 percent of the total value of the EITC in order to remove uncertainty. Figure 1 shows how the compensating variation (economic parlance for the amount a filer would be willing to give up) varies across demographic groups in our sample.

Figure 1

Our findings suggest that low-income tax filers are substantially uncertain about the amount they will receive in their annual tax refund. Specifically, tax filers whose financial status (and actual refund amount) has not changed report being uncertain. Uncertainty was largest among filers with dependents and among filers whose marginal tax rates had changed. This increased uncertainty may be the result of the complexities of qualifying for the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit.

Our research suggests that uncertainty about the amount of these two tax credits can erode a meaningful share of their value for recipients. These findings may help inform policymakers about the design of recent relief and stimulus efforts and of tax policy more broadly. More transparent programs may enhance recipients’ well-being at the same fiscal cost.

—Sydnee Caldwell is an assistant professor of business administration and economics at the University of California, Berkeley. Scott Nelson is an assistant professor of finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Daniel Waldinger is an assistant professor of economics at New York University.