Weekend reading: Fighting a new coronavirus recession edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

This is not a drill, writes Claudia Sahm. The U.S. economy is suffering mightily from the lack of certainty surrounding the new coronavirus, and policymakers must act to protect American workers and their families from feeling the effects of the tailspin. Sahm points to Equitable Growth’s book, Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy, published with the Hamilton Project last year, providing various policy ideas that can be implemented immediately to both fight a coronavirus recession now and protect and strengthen our economy before the next economic crisis hits. These policy recommendations were studied and tested after the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and would address the economic fallout of the new coronavirus. While it will likely mean spending billions of dollars, Sahm argues, there is no question that it must be done. In order to protect American workers and businesses from long-lasting economic harm, policymakers need to think big, spend lots, and act now.

Earlier this week, House Democrats proposed a package of policies that would be a great step in the right direction to address coronavirus’ impact—from health, safety, and economic standpoints—on the workforce. The only thing better than strengthening these programs now, writes Alix Gould-Werth, would be if these programs were expanded and strengthened permanently. The proposed recommendations include emergency Unemployment Insurance funding, free COVID-19 testing, and, importantly, a new federal paid sick days program that would allow all workers to earn paid leave in the event of an illness and provide an additional 14 paid sick days in emergency situations just like the one we are currently experiencing. Making these supports permanent rather than implementing them for this crisis alone would put in place structures to boost our economy before the next economic downturn, concludes Gould-Werth, ensuring that we are better prepared to deal with it when it inevitably occurs.

Providing access to paid sick leave is the best way to support American workers, especially low-wage workers and those in the service industry with little or no control over their schedules, argues Heather Boushey in an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times. It is also a proven way to reduce the spread of infections, by up to 40 percent. There are other actions that can be taken as well to support workers in the weeks and months ahead, and Boushey runs through some of the recommendations that are most likely to work in the almost-inevitable coronavirus recession heading our way.

We also must consider actions to protect specific industries in our economy from a coronavirus recession: namely, addressing the supply-chain weaknesses that have been exposed. The pharmaceutical, tech, and auto-manufacturing industries in particular are extremely vulnerable to periods of import and export restrictions or shipping and transport constraints, write Susan Helper, John Gray, and Beverly Osborn. Not only will a coronavirus recession impact large corporations, but small and medium-sized businesses will also suffer from supply-chain disruptions. The United States can prevent this in the future by building high-road supply chains, “whose greater collaboration between management and workers along the length of the supply chain would promote sharing of skills and ideas, innovative processes, and, ultimately, better products that can deliver higher profits to firms and higher wages to workers,” the authors continue. Implementing this change will protect U.S. firms, workers, and consumers during future pandemics by smoothing flows in global transportation.

A new working paper in Equitable Growth’s Working Paper Series looks at the paid leave programs in California and New Jersey, and finds that access to these programs increases mothers’ labor force participation following childbirth. In the year of their children’s births, writes Sam Abbott in a post on the research, mothers in California with access to paid leave demonstrated an approximately 20 percent increase in the probability of returning to work—an increase that continues up to 5 years after the birth of a child, according to the study. But the authors of the working paper note that the benefits of paid leave are more pronounced and longer lasting for white, highly educated women in both states than for their more disadvantaged peers. Abbott details why this may be the case, and why this paper comes at an important time, when other states and the federal government are considering various forms of paid leave programs.

Links from around the web

The United States has officially seen the first job layoffs as a result of the new coronavirus, along with a rapid market decline. Tourism and travel industries have been hit hardest, but the service, hospitality, and food industries have also begun to experience layoffs, report Abha Bhattarai, Heather Long, and Rachel Siegel for The Washington Post. And with people staying home, so-called social distancing, and ruptured global supply chains, many expect the worst is still to come. The authors interviewed several workers in various industries who have recently lost their jobs or whose hours have been cut—most of whom are younger, entry-level employees and gig economy workers—on how the uncertainty in their fields has affected them, drawing conclusions about how the wider economy may also be impacted in the weeks and months to come.

As more people globally are infected with the new coronavirus, there is increased pressure to develop a COVID-19 vaccine. But, Gerald Posner writes in an op-ed for The New York Times, big pharma may be an obstacle to that development, due to their concerns with and prioritization of profits and potential liability—meaning a ready-to-use, life-saving vaccine may not be available for at least one year. History shows us that large pharmaceutical companies are not willing to move quickly enough to develop and distribute effective vaccines when a new virus emerges, Posner continues, causing the United States and European allies to rely on other sources such as non-government organizations, academia, and philanthropies when outbreaks of deadly pathogens occur.

All industries will likely be affected by the new coronavirus and the resulting economic crisis, but recent events make it all the more evident that eldercare workers deserve better job benefits and protections than they currently have. As our populations ages, facilities and workers caring for our parents and grandparents are more in demand and have much less support than they should—an issue that is compounded with the outbreak of COVID-19, which is particularly dangerous for older adults, especially those who are more than 80 years old, writes Haley Swenson for Slate. More than ever, we need healthy eldercare workers, and we need to compensate them adequately for their work. “With low pay, demanding hours, and usually, no benefits, it’s easy to see why turnover for home health aides even outside a public health crisis is around 50 percent,” Swenson continues. But as the demand for these workers grows—and there is no sign of that demand slowing down or plateauing in the future—we must address the lack of support for eldercare workers and bolster the industry with public investments and stronger structural benefits before it’s too late.

So-called deaths of despair—or dying by suicide, alcoholism, and drug abuse—have been surging along the age spectrum for Americans without a 4-year college degree, report David Leonhardt and Stuart A. Thompson in The New York Times. A new study attributes the trend to the fact that working-class life is extremely difficult in the United States—more so than any other high-income country in the world. Inequality and healthcare costs have skyrocketed, while industries have shuttered factories and incomes have stagnated. The data show that the rise in deaths of despair has occurred across races and ethnicities as well, though life expectancy remains higher for white people than for their black counterparts, as do income and wealth levels. In a series of charts, Leonhardt and Thompson explain the study’s findings and present some solutions to reverse the trend.

Friday Figure

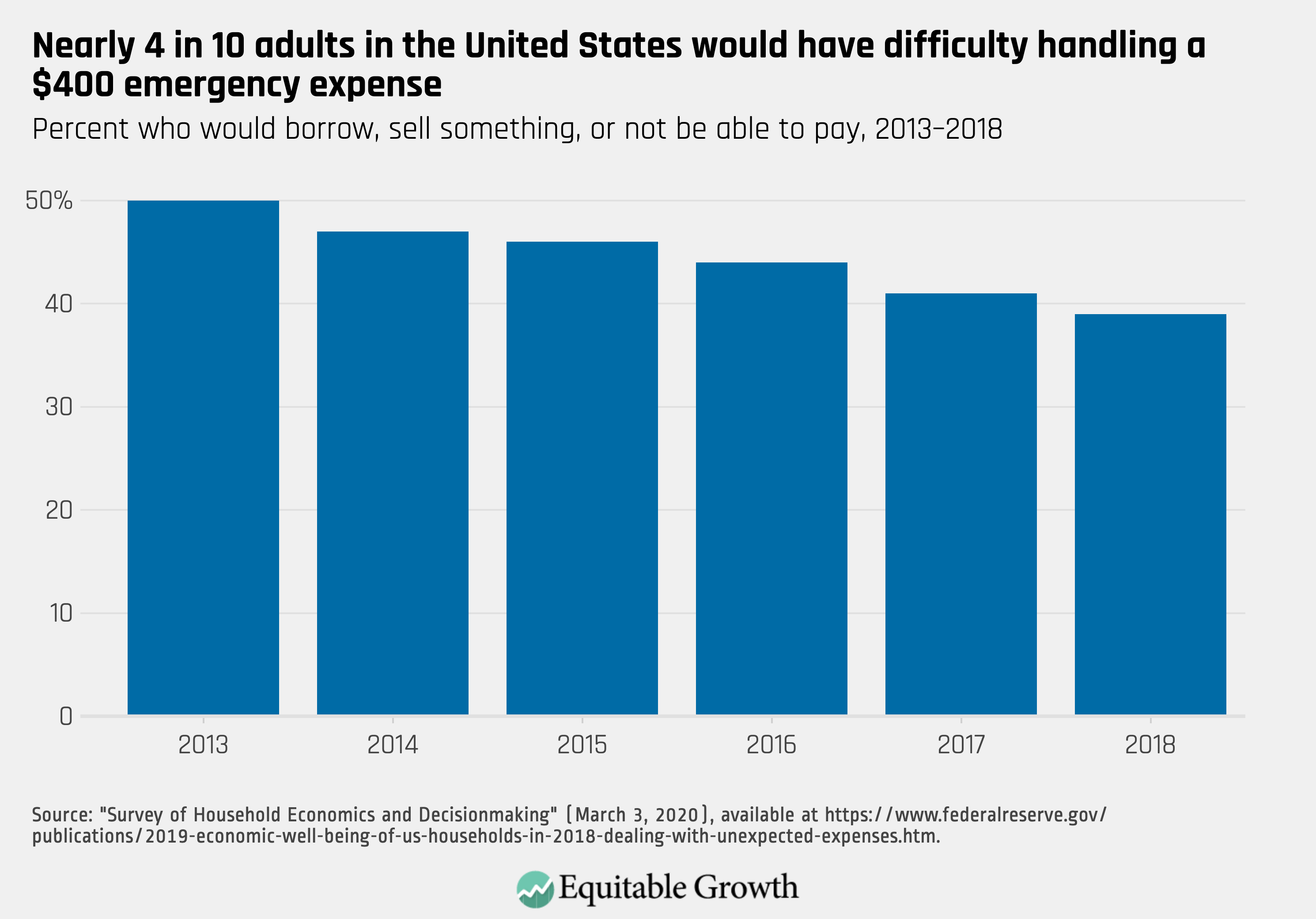

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “U.S. economic policymakers need to fight the coronavirus now” by Claudia Sahm.