Great Recession’s ‘lost generation’ shows importance of policies to ease next downturn

There is considerable research showing that recessions hit young college graduates harder than older graduates. Based on the evidence from research I’ve done for a new working paper, the damage (or “scarring”) is even worse and lasts far longer than anticipated. Indeed, the long-term consequences are comparable in magnitude to the short-run effects, roughly doubling the initial cost. The results suggest that policymakers need to do more to prepare for recessions and ameliorate their severity.

Economists have known for some time that in a recession, young workers, including new college graduates, are more likely to become or remain unemployed, lose access to training and work experience at a time in their careers when they need them most, and suffer from lost income both during unemployment and in the early years following a period of joblessness.

My research for a new working paper, which focuses on young college graduates in the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and its aftermath, suggests that the damage suffered by young workers in recessions lasts throughout their careers. Those who enter the labor market during recessions have permanently lower employment and earnings, even after the economy has recovered.

This long-term scarring argues not only for quicker and stronger action to counter recessions when they occur but also for putting in place policies that can be automatically triggered at the first signs of a recession to limit its depth and duration.

The Great Recession was the worst downturn since the Great Depression and wreaked havoc on U.S. workers and businesses. Unemployment rose by 6.5 percentage points and took nearly 10 years to get back to its prerecession level. Job losses amounted to 8.7 million. Perhaps more importantly, the prime-age employment rate, which measures the percentage of people aged 25–54 who are employed, fell by more than 5 percentage points to its lowest level in 25 years and, despite continuing tightening in the labor market, has not quite fully recovered after 10 years.

And yet, the long-term damage, while less visible, will cause more financial and career losses to cohorts of workers who entered the labor market during this period.

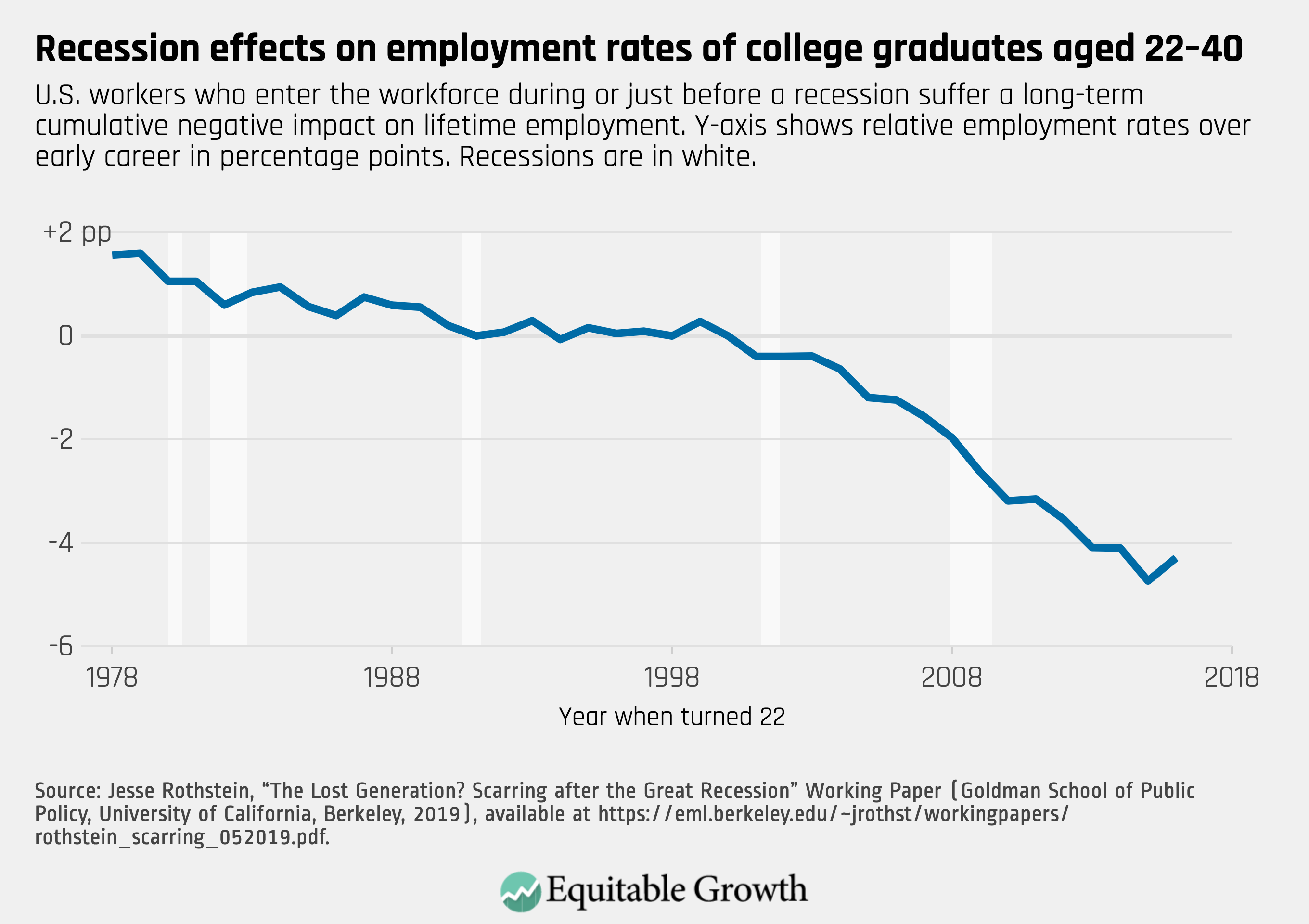

To obtain my results, I used the U.S. Census Bureau’s monthly Current Population Survey. I used the data to determine the degree to which poor employment rates of young graduates following recessions can be attributed to transitory shocks (the reduced demand for workers in the immediate wake of the recession) versus permanent differences that last long after the recession is over. In other words, once the overall labor market recovered, would there continue to be significant differences in employment outcomes (after adjusting for normal age differences) between those who entered during the recession and those who entered prior? (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows the drop in employment rates around recessions (white areas) for different cohorts of college graduates ages 22 to 40, with the years on the x-axis indicating the year a cohort entered the workforce. These estimates net out effects that are common to workers of all ages during the recession and disappear after the recession is past; they show only differences in outcomes for new graduates relative to older workers. The sharp downward slope for younger cohorts (those entering the workforce more recently) shows how much harder hit they were by the Great Recession than other workers. Workers from these cohorts saw their annual employment rates drop by 2 percentage points to 4 percentage points per year, relative to older workers in the same labor market. Those who were established in the workforce by the beginning of the recession—those who graduated college in 2005 and earlier—essentially returned to prerecession levels of employment by 2014. But those who entered after 2005 have not; their employment rates remain depressed even as the overall market has recovered.

These findings raise an important question. Is the damage permanent, or will the affected cohorts recover as they age, thus making the damage only temporary? Evidence from past recessions is informative here. In each of the recessions of the past several decades, graduates who entered the market during the period of economic weakness were scarred, just as seen in Figure 1. They recovered part of the damage in the years following the recession, but only part—half of the damage to recession cohorts has been permanent, manifesting as lower employment rates throughout their careers than for cohorts that graduated in better times.

For the Great Recession graduates, I estimate based on past recessions that this permanent scarring will reduce the average individual’s post-recession employment throughout his or her career by a total of approximately one week. Moreover, my research also shows that those scarred by recessions will earn lower wages when they are employed—about 2 percent less through the early years of their careers.

On an individual level, these losses might seem relatively small. Taken together, as an entire cohort of workers, they represent a very substantial loss of potential earnings.

How policymakers can ameliorate the consequences of the next economic downturn

Recessions are inevitable, even if economists can’t predict their timing or severity. One of the many mysteries of economic policymaking is why Congress and successive administrations have not done more to prepare in advance for upcoming recessions.

To be sure, there are already federal programs, known as automatic stabilizers, that act as counter-cyclical measures. Unemployment Insurance is a good example. When the economy slows and joblessness rises, more people receive these benefits, propping up their ability to spend and thus pumping additional money into the economy. The tax system acts in a similar way—removing less money from the economy as workers earn less.

Yet these existing automatic stabilizers are rarely sufficient. By the time policymakers act in the middle of a downturn, the system has already failed millions of workers (along with their families) who may have lost their jobs unnecessarily and/or suffered avoidably long periods of unemployment. There is no need to wait for emergency legislation. To reduce the damage to workers and families, we need to have plans in place before recessions arrive to speed recoveries and cushion those affected until the recovery comes. Such measures are especially effective when targeted to those with the greatest marginal propensity to consume—those who live from pay/benefit check to pay/benefit check.

Equitable Growth and The Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project released a book recently, titled Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy, that makes the case for six policies that either strengthen existing stabilizers or add new measures to be triggered when unemployment begins rising with a consistency that has always proven to signal a coming recession. We ought to consider these and other ideas now, before the next recession hits.

While it will be some time before conclusive data are available, my research clearly suggests that as a group, the young people who graduated just before, during, or immediately following the Great Recession will find it harder to be employed and will receive measurably lower wages and annual earnings throughout their careers. This has also been true of past recessions. This adds up to massive damage to the affected individuals, their families, and our economy, and argues strongly for measures to ameliorate the impact and length of future downturns.

—Jesse Rothstein is an associate professor of public policy and economics at the University of California, Berkeley and a member of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s Research Advisory Board.