2017 tax cut for pass-through business owners exacerbated inequality and failed to deliver economic benefits

Among the many regressive and ineffective elements of the Trump administration’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, one provision stands out as the most convoluted, unfair, and ripe for abuse. Section 199A of the Internal Revenue Code delivered a 20 percent deduction to the “qualified business income” of pass-through business owners. Pass-through businesses were already complicated, lightly taxed, and often used for tax avoidance.

Section 199A, also known as the pass-through tax cut or qualified business income deduction, made matters worse, though it has been difficult to analyze in a rigorous way. Thankfully, a newly revised working paper helps fill the gap, illuminating with empirical specificity just how regressive and ineffective Section 199A has been since it first came into effect in 2018. In short, this paper, as well as recent analysis from other sources, find that:

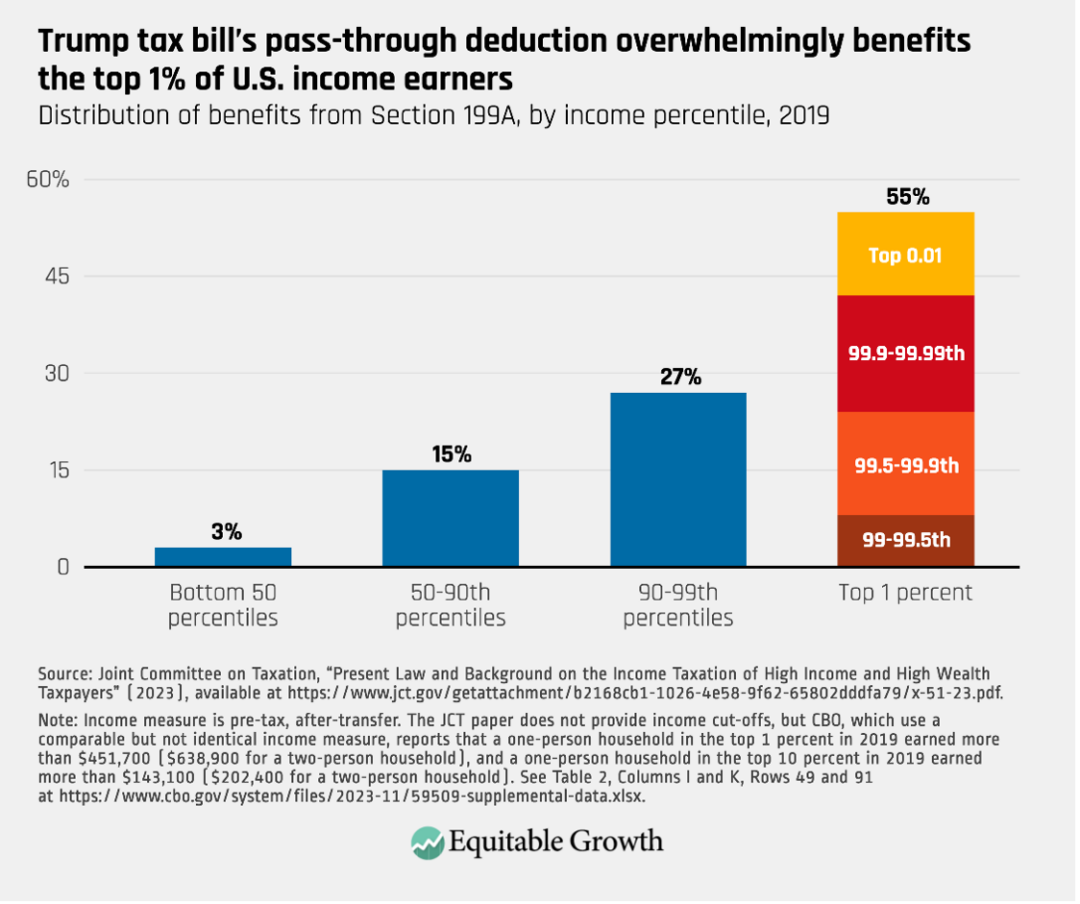

- More than half of the deduction’s benefits were captured by those in the top 1 percent by income in 2019, and 82 percent went to those in the top 10 percent.

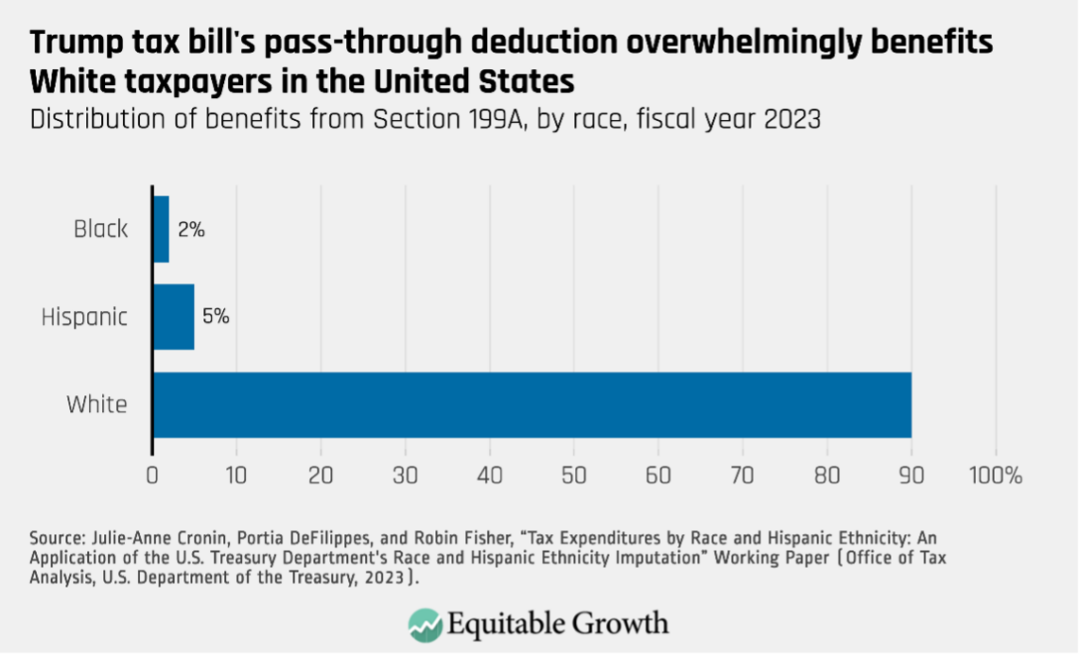

- By a ratio 45-to-1, the benefits of the deduction flowed disproportionately to White households, compared to Black ones, and it is likely that beneficiaries also skew male and old.

- Pass-through owners artificially adjusted the amount of labor income declared on their tax returns to maximize their qualified business income deduction, a costly form of tax avoidance.

- The pass-through tax cut did not produce an increase in business investment, jobs, wages, or output.

- Despite claims that the deduction would spur small business hiring, 45 percent of Section 199A deductions were generated by businesses that had no actual employees.

This issue brief will dive into these findings in more detail. It first provides some background on how Section 199A works, and then details recent estimates of who benefits and how much it costs. Next, it analyzes how certain taxpayers are gaming the system to maximize their deductions, then reviews findings on the provision’s lack of effect on real economic activity. The issue brief closes with a policy recommendation that Section 199A be allowed to completely expire as scheduled at the end of 2025.

How Section 199A works

How “qualified business income” is defined and who is eligible for the deduction are extremely complicated, and were the subject of intense, conflict-ridden lobbying both in the run-up to the passage of the Trump tax cuts in 2017 and in the writing of accompanying regulations.

An overly simplified summary is that qualified business income includes all business income other than wages, capital gains, and dividends (note that the latter two income categories already receive preferential treatment when “passed through” to owners), and that all pass-through business owners who make less than $191,950 are fully eligible.1 For those who make more than this amount, there are still a number of ways to receive at least a partial deduction, including by:

- Making less than $241,950, or2

- Not being engaged in a “specified service trade or business,” or SSTB, an inexact attempt to exclude professional services firms that rely on the reputation or skill of workers, such as lawyers, doctors, financiers, and consultants. To qualify, these high-income non-SSTB businesses must also either pay out a substantial amount of wages or have invested in a substantial amount of capital assets, such as real estate.3

Section 199A is also available, without limit, to those receiving real estate investment trust dividends and income from publicly traded partnerships, a major carve-out that helps high-income investors qualify for Section 199A despite being in otherwise-excluded professions and above the income thresholds.4

Who benefits, and at what cost?

Section 199A was a large, expensive tax cut, costing the federal government $415 billion over 10 years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation estimate at the time of passage. A more recent estimate from the committee put the cost at $174.2 billion just between fiscal years 2023 and 2025. In fiscal year 2025 alone, the U.S. Treasury Department expects Section 199A to cost $65.2 billion, making it the seventh-largest tax expenditure in the tax code that year.

This tax cut also was one of the most regressive provisions in the Trump tax bill since it targets benefits at already-wealthy business owners, who are disproportionately old, White, and male. In fact, an analysis from the Treasury Department estimates that 90 percent of Section 199A’s benefits in fiscal year 2023 will accrue to White households in the United States, compared to 5 percent accruing to Hispanic households and 2 percent to Black households. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

White households also received a larger benefit, averaging $410, compared to $91 for Hispanic households and $49 for Black households. Like all deductions, Section 199A is worth more to higher-income taxpayers who face higher marginal tax rates. According to investigative reporting by ProPublica, Section 199A delivered $1 billion in tax savings to just 82 ultrawealthy households, including a $67.9 million windfall to billionaire and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg.

A recent distributional analysis of the Section 199A deduction, which mimics one that was simulated right after the tax bill passed, finds that 55 percent of the benefits were captured by those in the top 1 percent by income in 2019 (roughly $638,900 for a two-person household) and 82 percent went to those in the top 10 percent (roughly $202,400 for a two-person household). (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

One reason for these regressive distributional findings despite the provision’s restrictions on high-income taxpayers is that those restrictions are ridden with loopholes. Additionally, the deduction’s phase-out threshold uses “taxable income” as the relevant metric, rather than the higher and more accurate “adjusted gross income.”5 Taxable income is generally calculated by reducing adjustable gross income by the $14,600 standard deduction, or a higher amount of itemized deductions.6

There also is evidence that a high proportion of lower-income taxpayers who are eligible for Section 199A did not claim it, likely due to the deduction’s complexity.7

In addition to being skewed toward high-income earners, it is likely that certain industries, such as construction and real estate, benefit disproportionately from Section 199A, while the phase-out rules substantially limit the deduction for the professional services, health, finance, and insurance sectors.

How are certain taxpayers gaming the system?

All of the aforementioned complexity built into Section 199A means there is ample opportunity for lawyers and accountants to help their wealthy business-owner clients further minimize their tax bills. Even before Section 199A, there was strong evidence that pass-through owners often mischaracterize labor income as business income in an attempt to avoid self-employment taxes. Section 199A only increased this perverse incentive, and there have been anecdotal accounts, based on investigative reporting, that executives have been exploiting this loophole.

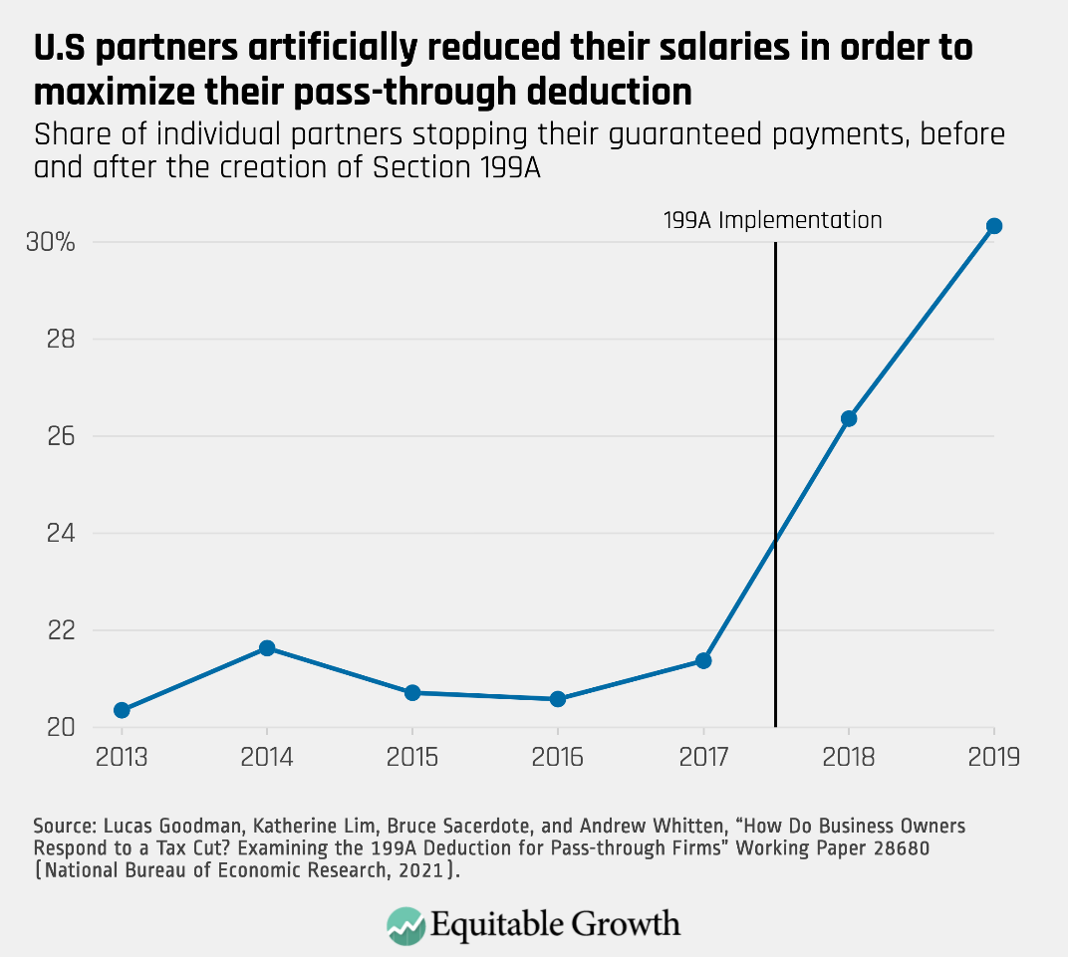

Now a newly revised working paper authored by Treasury Department economists Lucas Goodman and Andrew Whitten, Katherine Lim from the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank, and Bruce Sacerdote from Dartmouth College brings empirical specificity to the question. The researchers use administrative tax data and sophisticated econometric techniques to show that pass-through owners artificially adjusted the amount of labor income declared on their tax returns to maximize their qualified business income deduction. The research reveals that, as a result of Section 199A, many partners reduced or altogether stopped paying themselves “guaranteed payments,” a term of art for labor income that is not eligible for the pass-through deduction, so that income would instead flow to owners as profits, which is eligible. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

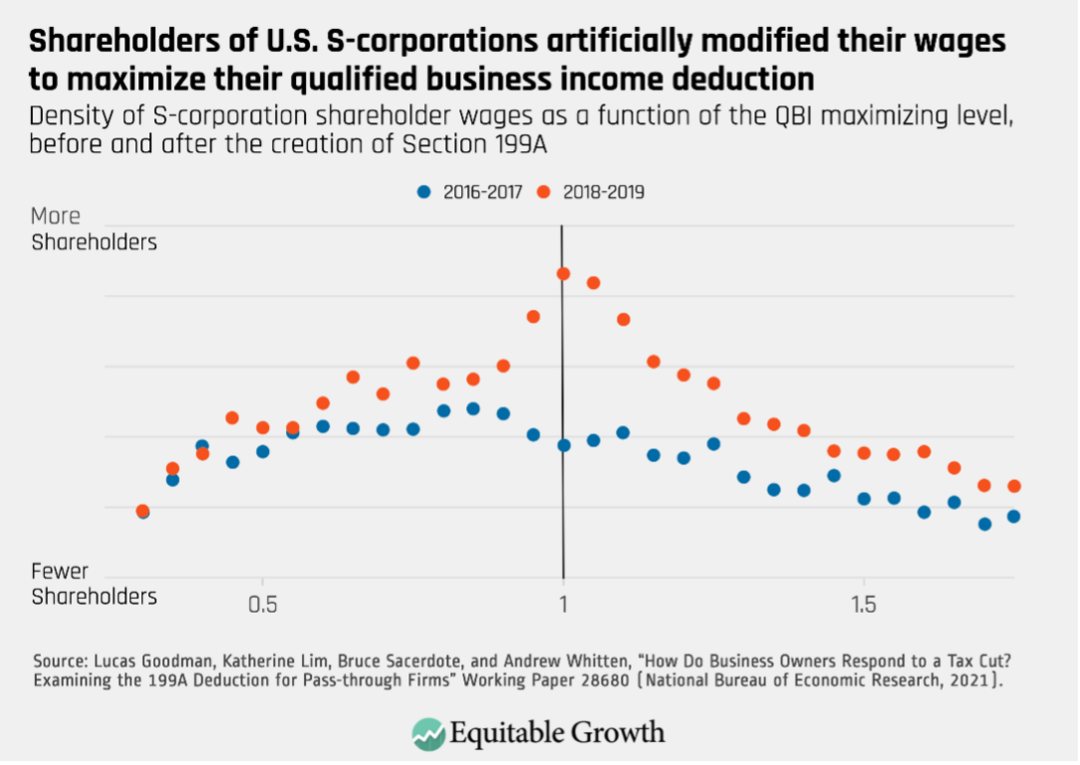

The same researchers also demonstrated how S-corporation shareholders exploited a flaw in Section 199A’s design. The flaw allows these business owners—who also are often considered employees of the corporation—to increase their own wages and count those wages toward the phase-out exception granted to firms that pay a certain amount to employees in order to qualify for a larger pass-through deduction.

The four researchers calculated what the qualified business income maximizing rate of shareholder wages would be for each firm—since wages are not themselves eligible for this deduction, S-corporation shareholders will only want to pay themselves the amount of wages that meets the phase-out exception threshold and no more—and then tested whether more firms did in fact pay that amount in the years immediately after Section 199A was created. There is strong evidence that S-corporation shareholders are using this ploy, which is a form of pure tax avoidance without any economic substance, to maximize their qualified business income deduction and reduce their tax liability. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

This working paper also finds evidence of business owners modifying their purported industry in order to qualify for the Section 199A deduction. As mentioned above, high-income owners of “specified service trades or businesses” are excluded from receiving the deduction. So, to test if high-income business owners were changing how they were describing their industry after Section 199A was created, the researchers zoomed in on S-corporation owners who described themselves as “consultants,” one of the restricted professions, in the 2 years before Section 199A went into effect.8

The researchers find that those same taxpayers were nearly four times more likely to claim they worked in a non-SSTB industry in the 2 years after Section 199A went into effect. These owners also were more likely to claim a non-SSTB industry than a control group of similarly situated low-income owners who would qualify for the deduction no matter what industry they were in. Though not dispositive, this is suggestive evidence that taxpayers are gaming the new deduction, claiming to be working in eligible industries in order to qualify for the deduction without actually responding to the new incentives in any substantive way.

There also is anecdotal evidence of pass-through firms splitting in two so that the parts of the business that qualify for the qualified business income deduction on their own do so. This often involves sophisticated legal and accounting maneuvers to get around the deduction’s income limits. The recent working paper was not able to cleanly test for these so-called cracking-and-packing tactics.

These efforts at tax avoidance are not costless. A rough estimate from the Tax Foundation put the compliance cost in 2021 for taxpayers who claimed the Section 199A deduction—including hours spent preparing their returns and money spent on tax professionals—at $17.8 billion. Considering the Section 199A deduction was a worth a total of roughly $51.8 billion in benefits to taxpayers that year, these represent very high administrative costs.

The risk that some workers would change their labor status from W2 employees to 1099 independent contractors in order to take advantage of Section 199A has not materialized, likely in part because Treasury regulations were strict on this issue (as well as the many labor law protections and other benefits associated with being a W2 employee).9

Section 199A’s effect on the economy

Section 199A did not produce a boom in U.S. business formation, job creation, or economic dynamism, to the extent that the provision’s proponents even offered these as rationales. In fact, the same recent working paper finds that Section 199A had no impact on real economic activity—no increase in tangible investment, no increase in the number of nonshareholder employees, and no increase in total employee wages over the first 2 years the policy was in place.

The results for 2020 and 2021 are more mixed, in part because the econometric techniques the researchers use lose power as they get further away from the moment of policy change and in part because of the many conflating factors introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in early 2020. The researchers nevertheless conclude that “taken together, the results suggest it is unlikely that large increases in capital and labor investments occurred due to the deduction in the first [four] years it was available.” This finding is somewhat corroborated by Joint Committee on Taxation’s analysis of 2021 tax records, which finds that 45 percent of Section 199A deductions were generated by businesses that had no actual employees.10

This was a very predictable outcome. In 2012, Kansas experimented with a similar reform, excluding self-employment and pass-through business income from the state income tax (and reducing income tax rates) in the name of promoting economic growth and increasing employment, especially among small businesses. That experiment unequivocally failed. A number of rigorous studies find that the reform did not produce any of the promised benefits, but instead led taxpayers to artificially reclassify income so that more would qualify for the exclusion—and reduced state revenue to such an extent that the legislature reversed the policy 5 years later.

Some proponents of Section 199A claimed it was needed to keep pass-through businesses competitive from a tax perspective with C-corporations, which received a very large tax cut in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Even with the pass-through deduction ultimately included in the bill, some analysts predicted it would lead to a “mass conversion” of pass-throughs incorporating to take advantage of the lower C-corporation tax rate. Though there is some limited evidence of certain S-corporations switching to C-corporations after the passage of the 2017 bill, switching of that kind seems to be rare.

One likely reason is that the tax considerations associated with choosing an organizational form are highly idiosyncratic and complex. The tax treatment of C-corporations, for example, becomes more favorable for their shareholders if firms retain earnings rather than distributes dividends, or if their early investors are eligible for the qualified small business stock exclusion, a potentially lucrative—and highly flawed—tax break on capital gains. Pass-through owners, in contrast, can often benefit from self-employment tax and net investment income tax loopholes unavailable to C-corporations.

The ideal tax system would be perfectly neutral between business forms, thus ensuring that tax policy is not distorting business decisions. Under the current system, though, some research suggests that many productive pass-through firms choose to remain artificially small—unable to access public equity markets because of their pass-through status—purely for tax reasons. This acts as a drag on hiring and economic growth. Our recent factsheet on pass-throughs goes into greater detail on these points.

But outside of creating a new integrated business tax regime, achieving the ideal of complete parity between business forms is challenging. And Section 199A only makes things more complicated, putting a higher premium on unproductive tax planning.

What can policymakers do about Section 199A?

Section 199A is scheduled to expire at the end of 2025. Extending the provision would cost between $700 billion and $980 billion over 10 years (from 2026 to 2035), and, according to the Tax Policy Center, another $722 billion between just 2036 and 2040. Extending the provision in its entirety would also violate President Joe Biden’s pledge that he will not extend Trump tax cuts for those making more than $400,000.11

Allowing the deduction to expire will mean a tax increase on pass-through business owners, but the evidence predicts that the high-income owners themselves will shoulder the vast majority of that burden, reducing inequality.

It also will only get politically harder over time to rescind the provision as more and more taxpayers come to expect it. And it could become a bigger problem in the future, potentially undermining other progressive reforms by being used as an escape hatch to reduce taxes for rich taxpayers who will get more creative at converting wage income into qualified business income.

Based on the evidence above, it is clear that Section 199A is an ineffective, expensive, and regressive tax provision, and, as such, it should be allowed to expire in full.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance I received in writing this factsheet from Samantha Jacoby, Gregg Polsky, and Jean Ross. All errors are my own.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. This is the threshold for single taxpayers in 2024. The 2024 threshold for married taxpayers filing jointly is $383,900. In the deduction’s first year, 2018, the thresholds were $157,500 and $315,000, respectively, but they are adjusted for inflation annually.

2. This is the threshold for single taxpayers in 2024. The 2024 threshold for married taxpayers filing jointly is $483,900. In the deduction’s first year, 2018, the thresholds were $207,500 and $415,000, but they are adjusted for inflation annually.

3. There is no clear economic justification for this distinction; more likely, it was simply an attempt to exclude politically disfavored professions.

4. For more on publicly traded partnerships, which are often in the oil and gas sector, see Laura Hinson and Kathryn Neely, “Publicly traded partnerships: Investors’ tax considerations” The Tax Adviser, October 1, 2022, available at https://www.thetaxadviser.com/issues/2022/oct/publicly-traded-partnerships-investors-tax-considerations.html. REIT dividends can also be used by shareholders of regulated investment companies to partially qualify for the Section 199A deduction, even though RICs are otherwise ineligible.

5. Though note that this policy design probably reduced the amount of state revenue loss from Section 199A, since most states are statutorily coupled to the federal definition of “adjusted gross income,” not “taxable income.” See Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “How States Should Respond to the Federal Tax Cuts for “Pass-Through” Business Income” (2018), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/how-states-should-respond-to-the-federal-tax-cuts-for-pass-through.

6. This is the standard deduction for single taxpayers in 2024. The 2024 standard deduction for married taxpayers filing jointly is $29,200. Both amounts are adjusted for inflation annually.

7. The Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration identified 887,991 tax returns in 2018 (processed as of May 2, 2019) that appeared to qualify for the qualified business income deduction, but no deduction was claimed.

8. One limitation of this analysis is that the researchers relied on the North American Industry Classification System, or NAICS, code the taxpayers put in their tax returns to determine business industry, but, as the researchers readily admit, that is not a perfect proxy for “specified services trades or businesses” and is not actually how the IRS determines eligibility, which is instead based on a facts and circumstances test. That said, the researchers show elsewhere in the paper that NAICS code is predictive of QBI-claiming behavior and deduction size.

9. The regulations established a rebuttable presumption that an independent contractor who had worked as an employee in a similar role for the same firm within the past 3 years should be treated as an employee for 199A purposes.

10. See Figure 6 and accompanying text, pp. 81–82, available at https://www.jct.gov/publications/2024/jcx-8-24/.

11. In 2020, then-candidate Biden proposed phasing out the deduction for those making more than $400,000. In 2021, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) introduced a similar proposal.