Women’s History Month: Systemic gender discrimination continues to harm working women amid the coronavirus recession

Women’s History Month is observed every March to celebrate the contributions of women politically, economically, and culturally throughout the history of the United States. It is an important month for commemorating the great contributions of women pioneers in economics such as the late Sadie Alexander, Joan Robinson, and Elinor Ostrom, and the current secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, Janet Yellen.

But with the widely felt impacts brought on by the coronavirus recession, it is also a time for acknowledging the struggles women are facing in the U.S. economy when it comes to the labor market and monopsony power, the child care crisis, and pay equity. Recent research demonstrates that these are all areas that have plagued women in the workforce, particularly women of color, historically and right up to today, and need to be addressed specifically as women claw their way out of this recession.

A recent “Expert Focus” from Equitable Growth highlighting scholars studying the well-being of workers during the coronavirus recession featured Michelle Holder, an assistant professor of economics at John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York. Holder’s research discusses the disproportionate impact of the current crisis on Black women and notes that these harms are rooted in historical and persistent disparities that crowd Black women into low-wage work with high layoff rates during economic downturns.

One explanation of these historical harms is part and parcel of the stratification research by William Darity Jr. of Duke University, Darrick Hamilton of the New School, Mark Paul of New College of Florida, and Khaing Zaw of Facebook Inc. They examine the intersectional wage gap that Black women experience due to the larger proportion of them earning lower wages and thus achieving a lower level of economic well-being. This wage gap is “unexplained” by the human capital model of wages and is therefore interpreted to be the result of outright racialized gender discrimination. The four scholars find that Black women are more likely to face a reduction in work hours, higher rates of unemployment, and exposure to coronavirus while at work, exacerbating the hardships women of color already face on the job.

Another economic phenomenon that disproportionately affects women is monopsony, a market structure that occurs when workers have few suitable outside job options, so employers use their greater market power to take advantage of these labor market conditions by pushing down wages for workers. Kate Bahn, director of labor market policy at Equitable Growth, and Mark Stelzner of the University of Connecticut demonstrate how women may be more likely to face difficulties in finding a job due to disproportionate care burdens and lack of access to wealth, leading to lower pay levels.

Bahn also examines how older women, who may be caregivers for family members or have their own health needs, are affected by how they search for jobs and thus are more vulnerable to monopsonistic labor markets. Monopsony, Bahn finds, is also more prevalent in female-dominated occupations, including nursing and teaching—professions that face disproportionate challenges during the coronavirus recession.

Yet women’s disproportionate responsibility for caregiving remains a primary determinant of their inequitable economic opportunities and outcomes. Equitable Growth Policy Analyst Sam Abbott details the struggles the U.S. child care industry faced leading up to the pandemic shutdown in 2020, including razor-thin profit margins and low median wages that put child care workers—a large majority of whom are women of color—at particularly high risk when the recession began. This dynamic, in turn, reduces the supply of child care services for working mothers.

Many working mothers, of course, cannot afford child care. A new working paper from Ariel Kalil, Susan Mayer, and Rohen Shah, all from the University of Chicago, highlights the economic distress brought on by COVID-19 for low-income working mothers. Their research surveyed 572 low-income families with preschool-age children in Chicago to understand the economic and social restrictions brought on by the pandemic. In particular, their research finds that mothers’ time providing child care has increased in the wake of school closings and stay-at-home orders, and that these mothers face substantial increases in stress and anxiety both around their newfound child care responsibilities and their economic conditions.

With working mothers increasing their demand for child care services, a renewed focus on addressing the already-fragile child care industry is necessary for tackling the needs working mothers are facing. Taryn Morrisey, associate professor at American University, proposes, in an essay included in Equitable Growth’s Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, solutions to meet the need for affordable, quality early child care in the United States. Morrisey argues that accessible child care is a necessary component of the U.S. economic infrastructure and, if adequately provisioned, will narrow socioeconomic and racial inequities while promoting parental employment and family self-sufficiency. And Equitable Growth’s Abbot argues that bold, wartime thinking is required, similar to what was needed to meet child care needs during World War II.

Similarly, ensuring that women are compensated fairly and are ensured greater protections during periods of unemployment is necessary for a swifter economic recovery and a more equitable economy. The U.S. economy is only just beginning to recover from an economic recession that disproportionately harms women. But even as that recovery takes hold, the research highlighted in this column demonstrates that these obstacles in the U.S. labor market facing women, and especially women of color, are pertinent now more than ever.

Consider Equal Pay Day, the marker of how far into the new year a woman must work to earn what comparable men earned during the prior year alone. In 2021, that day falls on March 24. Yet the experiences of women differ greatly based on race and ethnicity. Black women earn 62 cents for every dollar full-time, year-round White men workers earn, meaning their Equal Pay Day will fall on August 3, 2021. Even further on the distribution, Latina workers are required to work nearly 23 months to earn what White men workers earn in just 12 months, making just 55 cents on the dollar, compared to their White male counterparts.

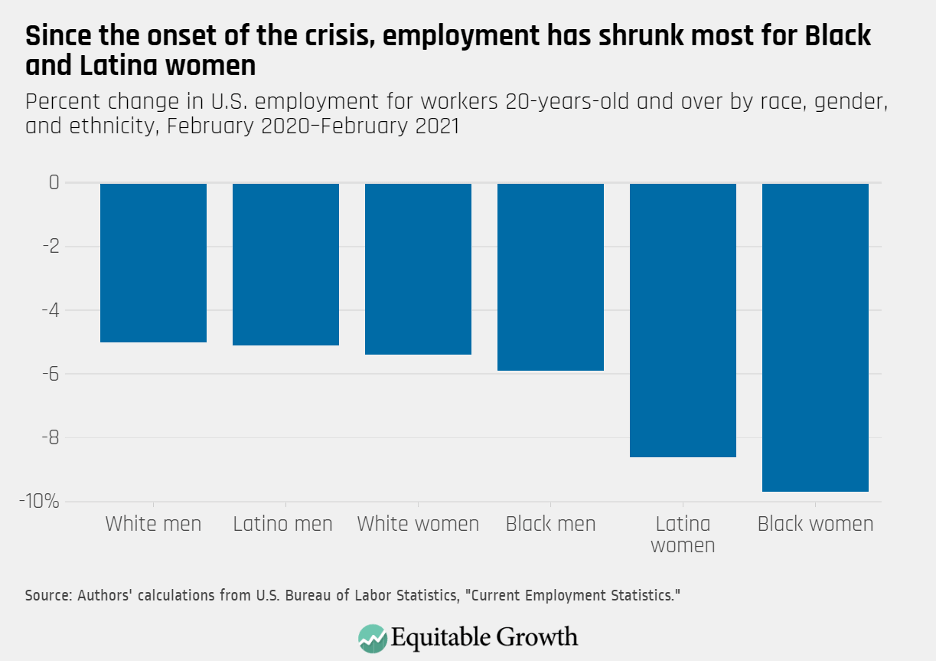

A recent column from Equitable Growth highlights how unemployment affects women workers amid the pandemic. Specifically, women workers are more likely to have lost their jobs than White men, with Black women and Latina workers facing the greatest risk of becoming unemployed at the onslaught of the coronavirus recession. Latina workers alone experienced a 22 percent drop in unemployment between January and April 2020. Indeed, since the onset of the coronavirus recession, Black women and Latina workers have faced disproportionate impacts to their employment, as seen in the figure below. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As the United States celebrates Women’s History Month and the great achievements of women, policymakers must not forget working women who have experienced disproportionate economic harms brought on by the coronavirus recession. Structural racism and sexism, alongside historical disparities in care responsibilities borne by women, laid the groundwork for the unique crisis facing women today, leading to starker outcomes for women, and women of color in particular. Whether it be pay equity, monopsony power, or the ongoing child care crisis, the United States must work to address everyday barriers women face in the workforce in order to create a stronger economy rooted in gender equity.