What the historically low U.S. unemployment rate means for women workers

Women’s History Month began with some good news. One of the key indicators reported in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly Jobs Report—the unemployment rate—documents an exceptionally good environment for workers in general and for female workers in particular. Last month’s Jobs Report showed that at 3.5 percent, the share of women who are actively looking for a job but don’t have one continues to be near a 65-year low. At 3.6 percent, men’s unemployment rate is currently slightly above the rate for women.

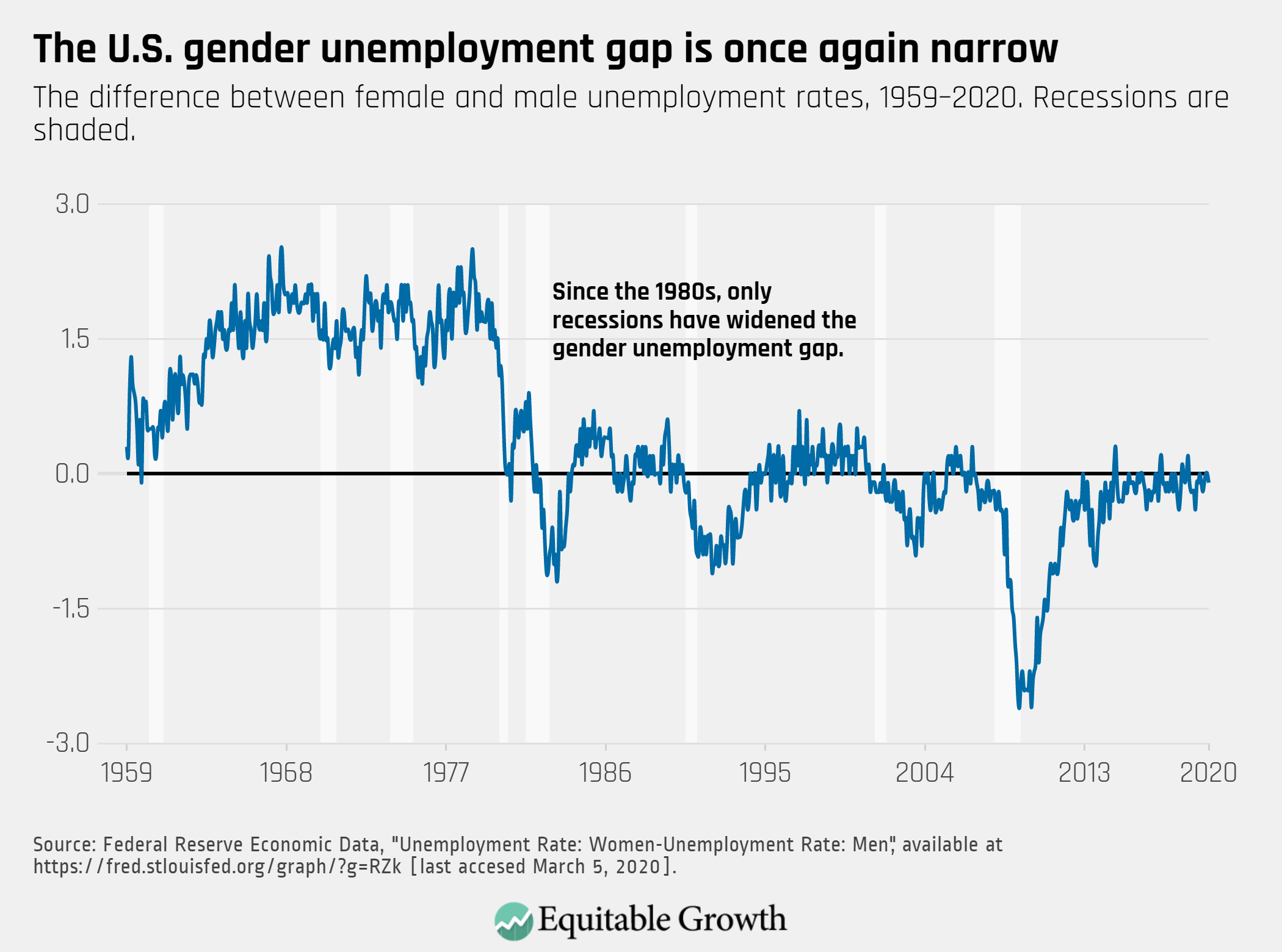

Prior to 1983, that was rarely the case. Research published in 2017 by economists Stefania Albanesi of the University of Pittsburgh and Ayşegül Şahin (at the time with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and now at the University of Texas at Austin) shows that for most of the post-World War II period and until the early 1980s, women’s unemployment rate was rarely below 5 percent and usually more than 1.5 percentage points above that of their male counterparts. In the ensuing four decades, however, the gender unemployment gap—the difference between the female and male unemployment rates—nearly disappeared except during recessions, when men consistently experience a higher joblessness rate. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

During the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and its aftermath, this relatively new phenomenon caught the attention of journalists, researchers, and policymakers, with some commentators even calling the economic downturn a “mancession.”

Some economists attributed men’s relatively higher unemployment rate to women boasting more college degrees. Because workers with higher levels of education tend to receive more intensive on-the-job training, they acquire specific skills that reduce employers’ incentives to lay them off.

Other researchers pointed to the “added-worker effect.” This happens when married women enter the labor force to make up for their husbands’ lost income. Additionally, most economists agree that at least some of the widening of the gender unemployment gap during the 2007–2009 recession was a consequence of men’s concentration in industries that are more exposed to fluctuations in the business cycle. In other words, because men hold the majority of jobs in sectors such as construction, extraction, and manufacturing, and because those sectors tend to be hardest hit by economic downturns, male workers are more likely to be unemployed during recessions.

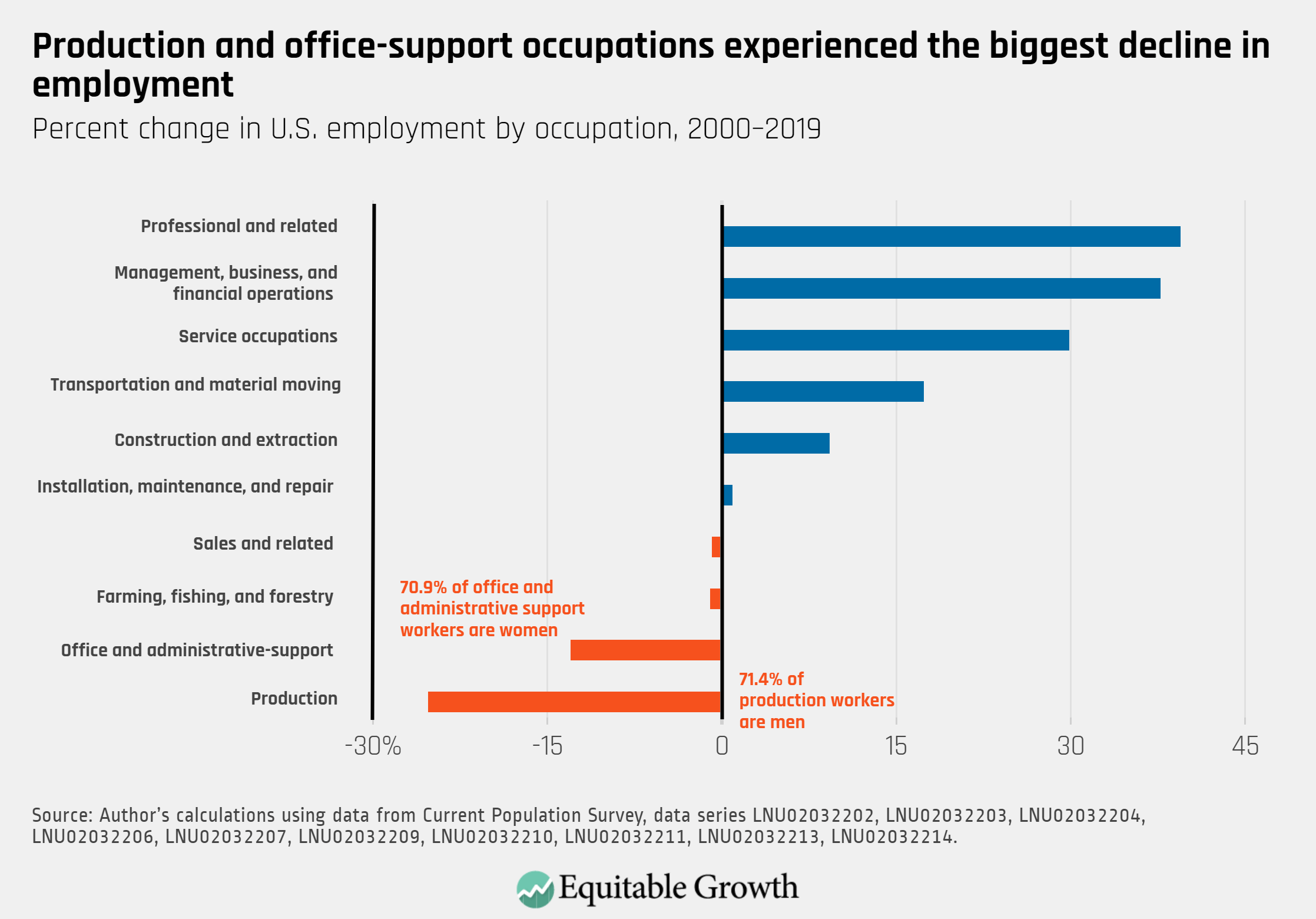

Yet this trend masks how changes in U.S. occupational structure have also affected women in the labor force. Even as discussions about joblessness, job displacement, and economic anxiety tend to center around the effects of deindustrialization in male-dominated sectors of the U.S. economy, occupations with a predominantly female workforce have also seen a big dip in employment. Office and administrative positions—occupations in which 70.9 percent of workers are women—lost 2.79 million jobs between 2000 and 2019. This drop was only surpassed by the decline in production, which lost 2.89 million jobs in the same 19-year period.

Moreover, many of the new jobs more open to women employees are failing to provide the economic security, earnings, and career-advancement opportunities of the lost positions. The decline in office and administrative-support employment is being offset by strong job creation in other women-dominated industries such as hospitality and healthcare services—two sectors that are projected to keep experiencing big gains in the coming decade—yet many of these are poor-quality, low-wage jobs that offer little in terms of benefits. The shrinking share of middle-skill, middle-wage employment—what economists call “job polarization”—is affecting both male and female workers. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The narrowing of the U.S. gender unemployment gap and the historically low female unemployment rate are evidence of important progress women have made in the workplace. In their research, Albanesi and Şahin show that the main driving force behind the decline in the gender unemployment gap was that women’s labor force participation rate began to catch up to men’s beginning in the 1980s. What sparked the change? Women postponed having children, family leave became more widespread, and the percent of mothers who quit their jobs during and after pregnancies declined. These and other factors made it less likely for women to experience unemployment when trying to return to work.

But it’s also important to highlight that the unemployment rate fails to capture many other factors that interact to shape both male and female workers’ labor market outcomes. Women’s median wage continues to grow more slowly than men’s, and the very occupational segregation that protects women from unemployment during downturns is responsible for much of the persisting gender wage gaps. At the same time, wage growth at the bottom 25 percent of the pay scale, where women are overrepresented, is growing faster than any other groups. These are factors that also need to be considered when looking at the gender unemployment gap going forward, particularly when the next economic downturn arrives.