Weekend reading: Vision 2020 release edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Equitable Growth this week released a book of 21 essays with innovative, evidence-based, and concrete ideas to shape the policy debate throughout this election cycle and for the next administration. The book, titled Vision 2020: Evidence for a Stronger Economy, covers a wide range of economic issues—including taxes, macroeconomics, racial and environmental justice, labor market reform, and antitrust policies—and is written by leading voices from academia, building on our conference last year of the same name. These ideas are needed now, more than ever before, due to the widespread and deep-rooted inequality that is present across our economy and society. Repairing the damage inflicted by this inequality will require a complete rethinking about how markets and government function, as well as bold ideas for ways to reimagine an economy that works for everyone, not just the wealthy few. This is likely to be the defining challenge of our time, and we hope that policymakers and leaders in the United States will be inspired to act by the suggestions presented in Vision 2020.

When will everyone who wants to work have a job in the United States, asks Claudia Sahm in her most recent column covering the Federal Reserve. Sahm examines the Fed’s mandate of full employment, which was under scrutiny this week during the semiannual Humphrey-Hawkins congressional hearings, where Fed Chair Jerome Powell testified. Despite the low rates of unemployment, questions remain about the Fed’s role in ensuring that all Americans who want to work can find a job that provides sufficient work hours, as evidence suggests that many people in the United States are not currently fully employed. Sahm reviews the history of the Fed’s “full employment” mandate, racial disparities in employment statistics, the role of inequality, and the Fed’s track record in this area over the past few years.

Links from around the web

Transparency about salaries helps to create more equitable workplace environments, especially for women and minorities, writes Susan Dominus for The New York Times. So, why is there so much secrecy around what we earn? Historically, employers have made concerted efforts to limit the discussion about pay within the office because it can be used against them in myriad ways, from discrimination lawsuits to union negotiations. But legally, thanks to the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, all workers are allowed to share salary information without fear of reprisal or being fired. And recently, almost 20 states (including the District of Columbia) have passed laws prohibiting punishment of employees for discussing their pay—yet, Dominus reports, recent studies show that two-thirds of private-sector employees are prohibited (either formally or informally) from doing so. The taboo surrounding salary sharing—and studies that show that pay transparency can increase worker unhappiness depending on where they are in the pay scale—may be to blame.

Kickstarter employees became the first group of big-tech workers to unionize, voting to form a union with the Office of Professional Employees International Union, reports Lauren Kaori Gurley for Vice. The decision to unionize comes during a period of growing labor organizing in the tech industry around issues from sexual harassment to carbon emissions. In fact, from 2017 to 2019, “the number of protest actions led by tech workers nearly tripled,” writes Gurley. While Kickstarter since its founding in 2009 has tried to distinguish itself from other big tech companies, the unionization sends a strong message to other tech workers across the industry.

The United States has been measuring the percentage of its population living in poverty the same way since 1963, writes Jeff Spross for The Week—and, he continues, that way in which we define poverty “is a conceptual trainwreck.” Not only has the measurement tool not been updated in nearly six decades, it is also based on a logic that barely makes sense. Spross goes through the history of the Official Poverty Measure, the more-recent release of the Supplemental Poverty Measure to attempt (quite badly) to address some of the shortcomings of the OPM, and the differences between how each looks at poverty. Ultimately, he argues, there is no silver bullet when it comes to measure poverty because how we define poverty “is an inescapably political question, and an inescapably moral one.”

Friday Figure

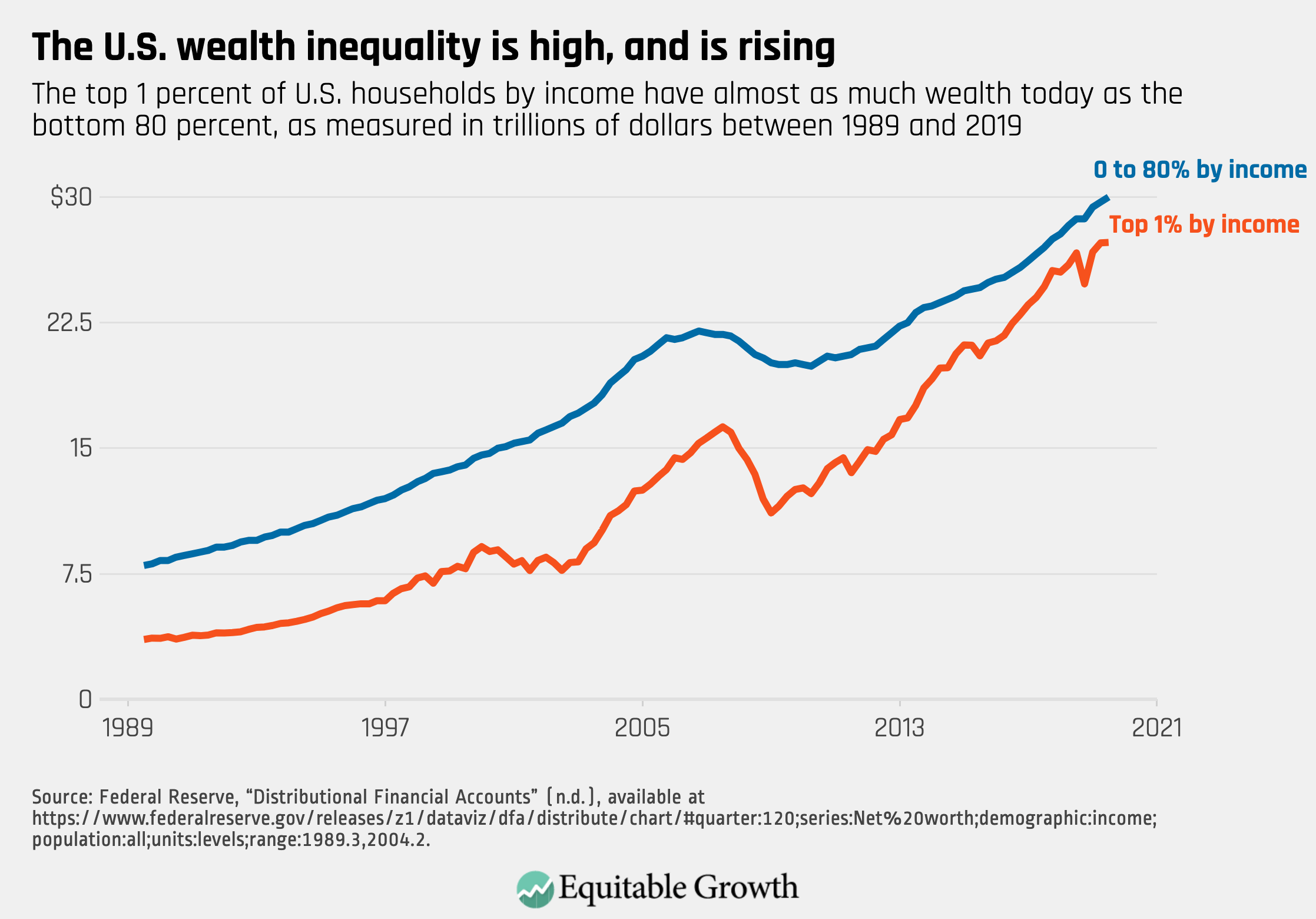

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “When will everyone who wants to work have a job in the United States?” by Claudia Sahm.