Weekend reading: The impact of COVID-19 relief packages on the U.S. economy and workforce edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

After approving $5.3 trillion in coronavirus relief legislation since March 2020, policymakers in Congress are now debating whether to pass two additional medium- and long-term investment packages: President Joe Biden’s $2 trillion American Jobs Plan and $1.8 trillion American Families Plan. Many are wary of increasing spending and want to make sure the new legislation will result in sustained economic growth that is equitable. Michael Garvey explains why the impact of previous coronavirus aid can provide helpful insights into the future economic impact of these two new investment proposals. Garvey looks at expanded Unemployment Insurance, the Paycheck Protection Program, and direct aid to specific sectors of the U.S. economy such as aviation and restaurants to discern whether investments these and others were effective. He then describes the relationship between these programs and others within President Biden’s two proposed investment packages, urging Congress to act to address the medium- and long-term challenges facing the United States with the same resolve with which it passed short-term emergency relief against the coronavirus pandemic and recession.

Join Equitable Growth and the Groundwork Collaborative next Tuesday, June 15 from 2:00 p.m. – 3:30 p.m. for a virtual event on improving data infrastructure to address racial disparities in U.S. society and the economy. Shaun Harrison previews the event, explaining why data disaggregation is so important for economic and public health data amid the coronavirus pandemic and recession. Harrison shows how seemingly race-neutral or “colorblind” policies are a myth and how data disaggregation can effectively ensure that our nation’s collective statistics provide accurate views of the lived experiences of all Americans, thus guiding policy to be more effective and targeted as well.

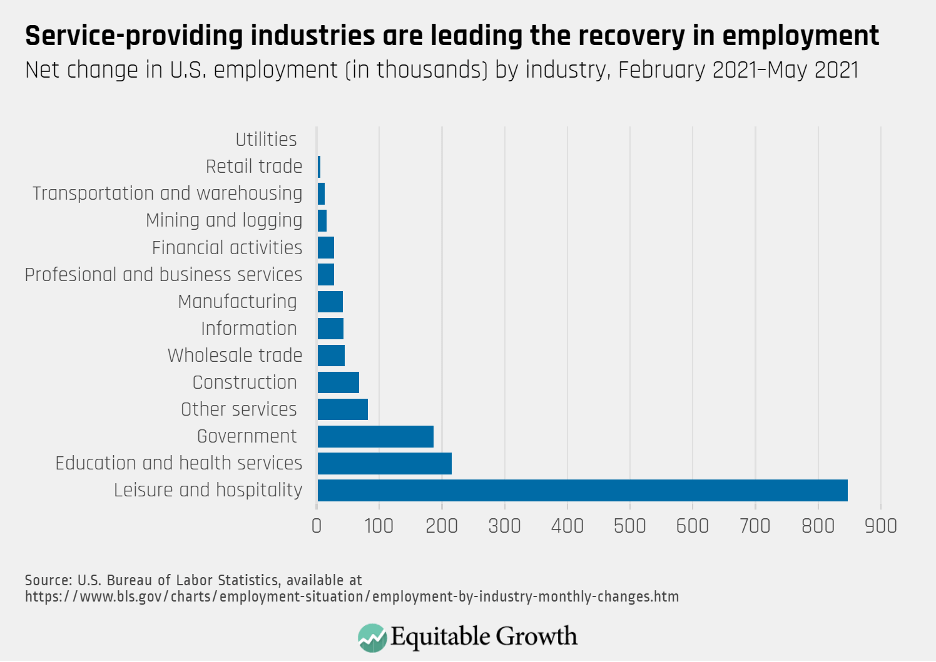

Last week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ highly anticipated Employment Situation Report for May 2021 revealed gains of 559,000 jobs, with the overall unemployment rate declining to 5.8 percent. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming break down the data in a column and a series of graphics. They write that the job gains have been especially strong in service-providing industries, which is good news for these hard-hit sectors, and economists predict that this trend will continue as vaccination rates keep rising and there is more public demand for entertainment, dining out, and other in-person services. While the May Jobs Day report was a welcome improvement from April’s report, which was unexpectedly low, it nevertheless reveals some troubling trends. The share of U.S. working-age adults with a job is still 3.3. percent below its pre-coronavirus recession level, the labor force participation rate remains at roughly the same level it was in June 2020, and workers of color still have significantly higher rates of unemployment compared to their White peers.

Earlier this week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its monthly data on hiring, firing, and other labor market flows from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, better known as JOLTS, for April 2021. This report doesn’t get as much attention as the monthly Employment Situation Report, but it contains useful information about the state of the U.S. labor market. Bahn and Sanchez Cumming put together four graphs highlighting key trends, including that the quits rate reached a series high of 2.7 percent with nearly 4 million workers quit their jobs in April, signaling higher worker confidence about the labor market.

Links from around the web

Though some companies in specific sectors—mainly those that frequently don’t pay very well or ensure good working conditions—are complaining about not having enough job applicants for the number of openings they’re posting, cutting expanded Unemployment Insurance benefits or requiring proof of job searches is not the appropriate response, says Marketplace’s Kimberly Adams. She argues this just attempting to return the labor market to the way it was operating pre-pandemic. The problem is, many people don’t want to return to their previous employment situations. And requiring them to do so may fill short-term openings but won’t necessarily lead to sustainable, high-quality job matches. Adams looks at the long-term economic benefits of letting workers stay on unemployment a bit longer in order to make sure they’re able to get a better job that pays more and is well-suited to their skillset. These kinds of job matches are good for the economy and recovery because workers ultimately are more likely to stay in these positions, leading to prolonged employment, improved well-being, and positive overall economic growth.

The coronavirus pandemic is not the first one to create a shift in labor market dynamics in which workers make new demands of their employers. Those who argue that labor shortages are being driven by higher Unemployment Insurance checks are ignoring the likelihood that other factors, including caregiving responsibilities and health concerns, are keeping workers out of the labor force, in addition to a desire to be paid more. In fact, writes Spencer Strub in The Washington Post, labor shortages are well-documented occurrences in post-pandemic economies, dating back to the 14th century Black Death plague. Pandemics provide workers with so-called powers of exit, or the ability to quit their jobs, and worker voice, or the ability to assert demands for anything from better conditions to higher pay. Strub details the history of repression and strikes that followed the Black Death in which workers demanded more from their governments, employers, and leaders and were punished for doing so—but which also led to higher wages. Strub cautions against policymakers reacting harshly against the labor shortages of the post-pandemic economy, arguing that this is an opportunity to rebuild the structural deficiencies of the labor market.

A recent opinion essay in The New York Times by Paul Krugman looks at President Biden’s almost $5 trillion budget proposal and the $3.6 trillion of it that will come from new revenues. The Biden administration has promised repeatedly to not raise taxes on households making less than $400,000 per year, which means this revenue will have to come from higher taxes on corporations and high-income Americans. Krugman asks whether it’s possible, wise, and effective to pay for a better America by taxing the rich. To the first two questions—possible and wise—he says yes, but regarding effectiveness, Krugman replies that it’s complicated. He details the three main critiques of President Biden’s approach, rebutting them where appropriate, and concludes that the administration’s proposals are likely to accomplish their goals, while cautioning against watering them down to appease more moderate policymakers in Congress.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “U.S. jobs report: Amid robust employment gains in May policymakers need to consider the future direction of demand-driven employment growth across industries,” by Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming.