Weekend reading: Supporting workers, regardless of employment status, edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

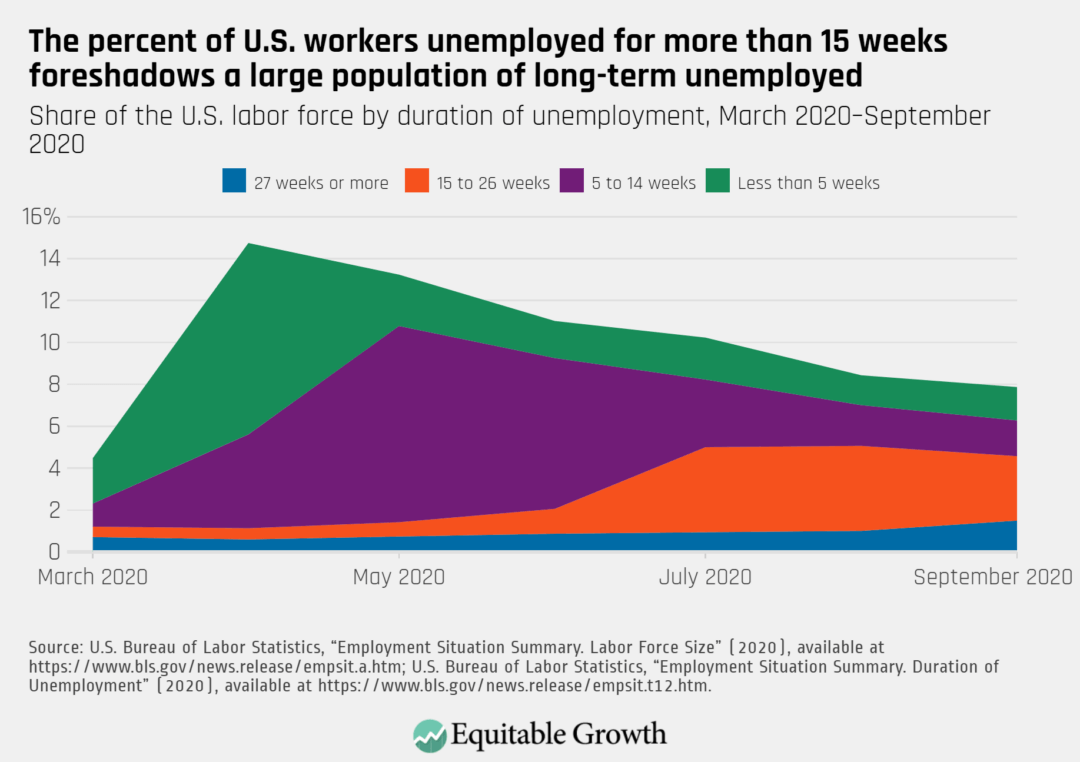

The coronavirus recession is resulting in millions of Americans either laid off or furloughed as businesses around the country close either temporarily or permanently due to the public health crisis. This jobs crisis is accompanied by record-setting levels of Unemployment Insurance claims—and these don’t even include the many more workers who are eligible but do not apply for benefits or wrongly believe they are not eligible. This in turn reflects the severe stigmatization in our society of joblessness and being unemployed—a stigma that threatens both our future economic recovery and the psyche of millions of capable workers let go through no fault of their own. Peter Norlander examines the effect of this stigma against the unemployed—labeling them as lazy, less productive, and personally at fault for not having a job—amid the coronavirus recession. He finds that this vilification, along with the existing faults within the Unemployment Insurance system, inhibits the delivery of jobless benefits to workers, leads to discrimination in hiring, and can have lasting damage to workers and the U.S. economy. Norlander concludes with several policy recommendations to address this stigma toward the unemployed, explaining why these suggestions would help unemployed workers re-enter the job market quickly and efficiently, and thus support the broader economy.

Student loan debt is a longstanding problem for workers, especially younger and lower-income workers, in the U.S. labor force. But an in-depth look at the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances reveals that this crisis ballooned in recent years—and it is likely getting even worse amid the coronavirus recession. In fact, average student debt-to-income ratios are now 0.56 among those adults who have student debt, falling most heavily on those households in the bottom 50 percent of the income distribution and especially on Black Americans, write Raksha Kopparam and Austin Clemens. Though some debt forbearance was provided in one of the coronavirus relief packages passed in March, and other programs such as income-based repayment plans attempt to alleviate debt burdens more generally, much more is needed to fully mitigate the effects of the student loan crisis on households across the country. Kopparam and Clemens analyze the data, summarize its main findings, and conclude with the policy implications of rising student debt-to-income ratios.

New research on a German law requiring varying levels of worker representation on some boards of directors shows that this representation does no harm to revenues or corporate profits while giving workers a much-needed voice in corporate decision-making. The law was overturned for new companies in 1994 but upheld for certain businesses already in existence, providing researchers with natural setting for testing the effect of including workers on boards. Kate Bahn summarizes the new paper, which found that when worker and shareholder representatives hold equal or near-equal power on boards, they operate by consensus rather than contention. This consensus yielded no significant impact on overall wages or employment, according to the study, alongside a slight increase in capital assets. More significantly, Bahn writes, when workers were included on boards, the study found an increase in worker productivity, with added values accruing mainly to capital and not labor, as well as a noteworthy reduction in outsourcing, with no meaningful effect on profits and revenues. This suggests that worker representation does not lead to negative outcomes for companies, such as bankruptcy.

Earlier this week, the U.S. Census Bureau released new data on the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on workers and households. Austin Clemens, Kate Bahn, Raksha Kopparam, and Carmen Sanchez Cumming put together five graphs highlighting important trends in the data, including the racial disparities in food insecurity, in the ability to pay household expenses, and in loss of income since the start of the recession as well as the impact of the coronavirus on students’ postsecondary education plans.

Head over to Brad DeLong’s latest Worthy Reads, for his takes on must-read content from Equitable Growth and around the web.

Links from around the web

The majority of Americans believe the U.S. economy is rigged against them, writes Samantha Fields for Marketplace. In fact, according to a recent poll, more than 80 percent of Black Americans, 70 percent of women, and two-thirds of Americans overall feel that the economy works better for some people than it does for others—namely, the wealthy, the powerful, and White Americans while everyone else gets left behind. Fields examines the data and its implications, particularly amid the coronavirus recession as millions struggle to pay basic expenses, and compares this year’s results with those from similar polls taken in 2016. She interviews several people across the country and varying demographic groups for their takes on who is benefitting from U.S. economic growth and why some people have it better than others.

It’s no secret that the coronavirus pandemic caused a child care crisis in the United States. Many schools are operating virtually or offering only part-time in-person learning and child care centers are closing. It’s also no secret that women tend to shoulder the majority of home responsibilities, including child care. So, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the pandemic is forcing women out of the labor force in much higher numbers than men—four times as many in September, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s jobs report for last month. NPR’s Andrea Hsu reports that this trend is hitting even the most successful women, many of whom are sidelining their hard-earned careers to take care of overwhelming household needs. This may well put many of their future promotions, earning power, and leadership positions at risk, Hsu continues, threatening a generation of gains for women in the workforce. The uncertainty surrounding the pandemic and how much longer it will continue to wreak havoc on U.S. society and the economy only adds to this rolling crisis.

New research shows that access to paid sick leave is an essential tool in reducing the transmission of the coronavirus. The study, summarized by HuffPost’s Emily Peck, looked at the impact of the emergency paid sick leave benefit in early coronavirus legislation, which provided 10 days of sick leave for workers with COVID-19 working for companies with fewer than 500 employees. It found that this emergency benefit prevented up to 400 cases of coronavirus per day per state, or roughly 15,000 cases prevented in the United States per day. Though experts say paid sick leave is not a “silver bullet,” it does slow the spread of the virus and can be extremely effective at doing so. Peck writes, however, that the emergency paid leave benefit is set to expire at the end of this year even though the coronavirus will certainly still be spreading throughout the country. What’s worse, the United States does not have a universal paid sick leave program to pick up where this emergency benefit leaves off. A universal paid leave program is long overdue: The United States is the only developed country in the world to not offer such a benefit for all workers, which some experts argue may be why case numbers in the United States have been so much higher than in other comparable nations.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Addressing long-term U.S. unemployment requires confronting the stigma against the unemployed amid the coronavirus recession” by Peter Norlander.