Weekend reading: Racial and gender discrimination in the labor market edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The U.S. labor market is difficult to navigate and that is especially the case since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and recession, with record-high unemployment and an economic contraction ravaging the economy since March. When the statistics are broken down by race and gender, an even bleaker picture appears, showing that Black and Latinx workers and women workers in particular are bearing the brunt of this economic downturn. These groups of workers also tend to receive lower wages than their White and male peers, according to a recent working paper that was the basis of a policy report, published this week, by Kate Bahn, Mark Stelzner, and myself. These wage discrepancies can’t be explained by differing skills or education levels among these groups of workers. In fact, the working paper finds that workers of color, particularly Black and Latinx workers, women, and those at the intersection—Black women and Latina workers—face wage discrimination due to lower levels of wealth and more household responsibilities. These factors make them more vulnerable to exploitation and less likely to leave a job—even when they are being paid too little for their labor. Bahn, Stelzner, and I recommend several areas where policymakers can act to close the racial and gender wage gaps, including restoring worker power, reducing racial wealth inequality, and reinforcing family economic security.

As millions of American workers are laid off and small businesses are struggling amid the coronavirus recession, U.S. financial markets are booming and wealthy people keep getting wealthier. The reason behind this seeming paradox lies in the policy choices made over the past 40 years, exacerbating inequality across the economy and society. Amanda Fischer looks at both coronavirus-era policies and various policies that preceded them to show where this break between the fates of Wall Street and Main Street began. From antitrust law and the dominance of Big Tech companies to monetary policy and the Federal Reserve’s interventions in the bond market, Fischer walks through why some firms and people are doing great right now and why that isn’t trickling down to the many others who are being left behind. Fischer concludes with several policy ideas that could reverse this trend and help ensure a strong recovery for all Americans and businesses—not only from the coronavirus recession but from future recessions as well.

Heather Boushey wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post recently that examines why U.S. stock markets rallied quickly after plunging at the start of the coronavirus recession while the real U.S. economy and so many U.S. workers and their families continue to suffer. She explains how income and wealth inequality enabled the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 indexes to recover largely on the back of the five Big Tech companies in those indexes, but that smaller firms in the Russell 2000 index fell in value. She points to more economic data to caution that U.S. stock markets cannot sustain their gains indefinitely without a recovery in the real economy.

Head over to Brad DeLong’s latest Worthy Reads for his takes on must-read content from Equitable Growth and around the web.

Links from around the web

While unemployment numbers, in aggregate, seem to be decreasing from their peak in April, dropping from 14.7 percent to 8.4 percent in August, a closer inspection of the data shows that much of this improvement has been for White workers. HuffPost’s Emily Peck reports that the unemployment rate for White workers is at 7.3 percent, while Black workers’ jobless rate is still in double-digits, at 13 percent—indicating that White workers are getting hired back almost twice as fast as Black workers. Black workers have long had unemployment rates that are higher than that of their White peers due to structural racism and discrimination, but at the start of the coronavirus recession, Black and White workers were laid off at similar and high rates. It appears, however, that the racial unemployment divide may soon widen once again as businesses reopen and rehire White workers more quickly. And as the child care crisis continues to burden working parents, Peck writes, Black women workers will bear the brunt of this, since household responsibilities fall disproportionately on them. Black workers are getting left behind, and policymakers are not acting to address this issue with the urgency it requires—or at all.

Contrary to what many economists argue is the cause of racial and gender wage divides—a so-called skills gap between White men workers and their otherwise-similar peers—Annelies Goger and Luther Jackson write for The Brookings Institution that policymakers instead should focus on an opportunity gap in the U.S. labor market. The skills gap narrative doesn’t take into account social dynamics that stunt many workers’ career advancement and job options, and therefore does not provide an accurate picture of the obstacles faced by large swaths of the labor force in the United States. This leads to misinformed policy choices that will not solve the real issue at hand. Instead, Goger and Jackson argue that policymakers should look at the opportunity gap—the disparity in access to a good education, economic security, high-quality jobs, and career mobility—in order to cultivate and invest in talent, innovation, and general well-being. Goger and Jackson conclude with several policy solutions to address these issues specifically and explain why they are necessary for lawmakers interested in reducing inequality in the United States.

The rampant inequality prevalent in the U.S. economy over the past several decades made the nation more vulnerable to the economic and public health crises brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. In a TIME magazine article, Nick Hanauer and David M. Rolf show how the upward redistribution of income has cost American workers dearly—how the top 1 percent took $50 trillion from the bottom 90 percent over the past 40-plus years—and how that wealth did not trickle down to all Americans, as some economists predicted it would. Hanauer and Rolf explain in depth how this inequality holds back U.S. economic growth and limits who prospers from that growth, and how it made us less resilient and primed our system to be ravaged by the coronavirus pandemic and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. They also demonstrate, using data from a recent RAND Corporation working paper, what American workers would be making across the income distribution had this inequality not taken hold—and, unsurprisingly, the vast majority of workers are earning only a fraction of what they could be earning. In fact, they find, inequality is costing the average full-time worker $42,000 per year.

Friday figure

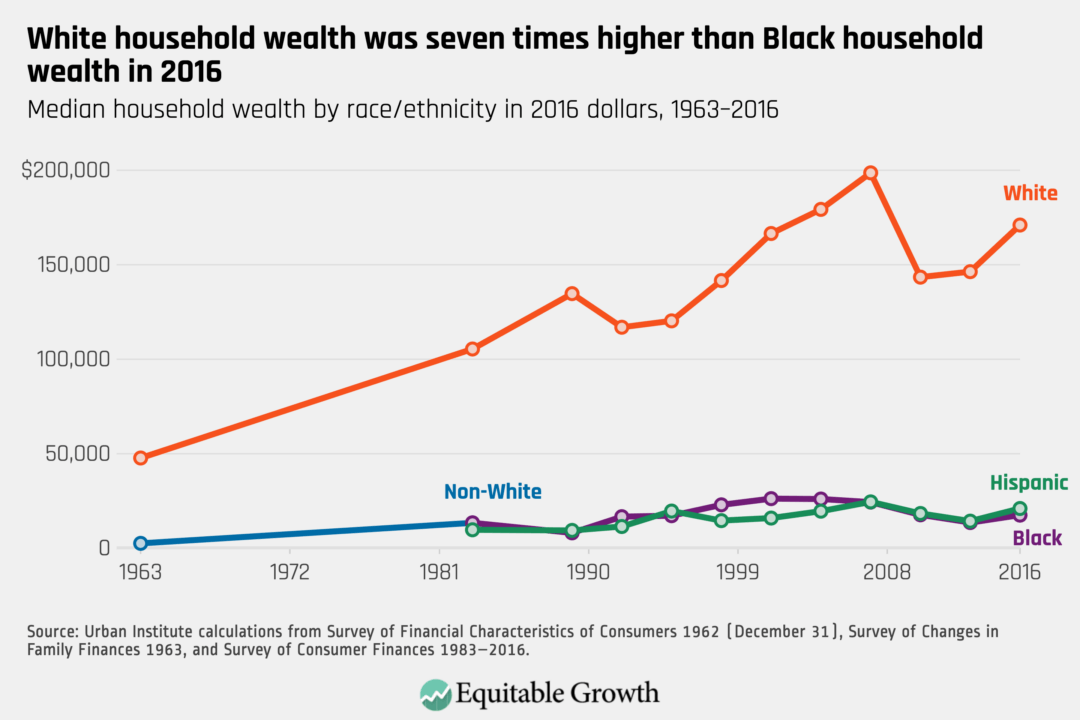

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Reconsidering progress this Juneteenth: Eight graphics that underscore the economic racial inequality Black Americans face in the United States” by Liz Hipple, Shanteal Lake, and Maria Monroe.