Weekend reading: Antitrust enforcement and the FTC’s authority edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

In April, the Supreme Court in AMG Capital Management LLC v. Federal Trade Commission unanimously struck down the Federal Trade Commission’s authority to require companies to give up profits they earn by violating U.S. antitrust laws and to require companies to compensate the victims of those violations. These two remedies—disgorgement and restitution, respectively—are the focus of two new Competitive Edge posts.

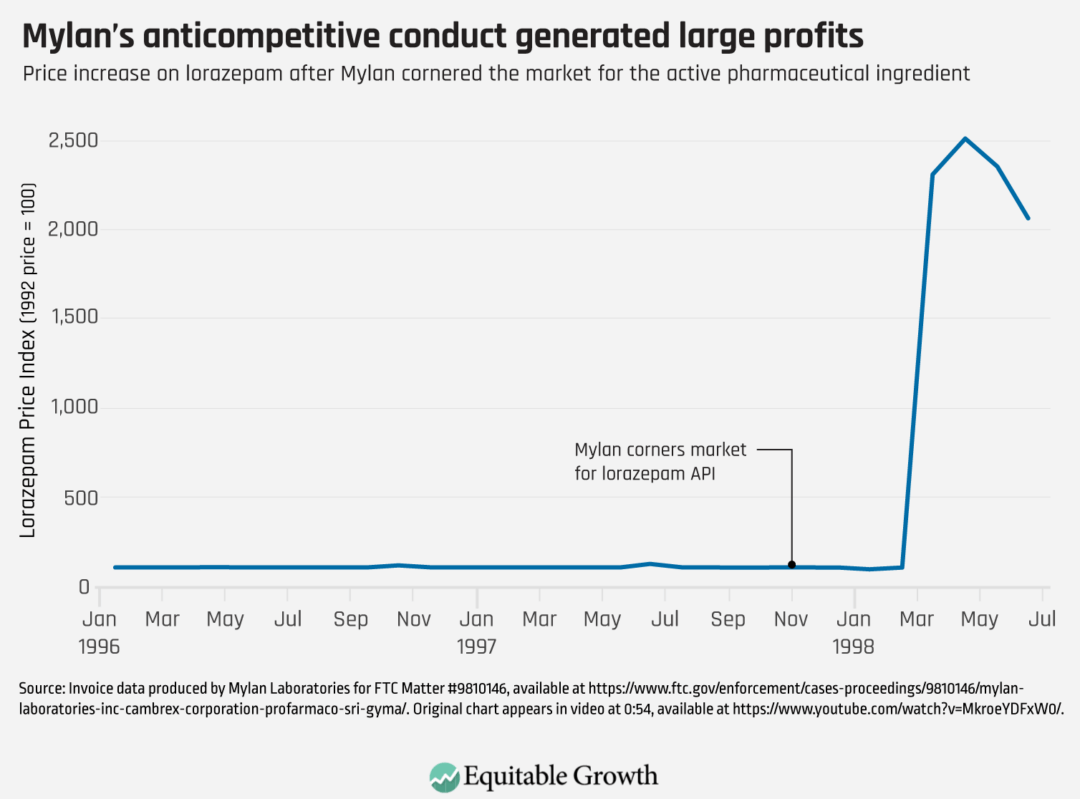

- In one, Michael Kades takes a glass-half-empty view of the Court’s decision, arguing that it deprives the FTC of a critical deterrent of anticompetitive conduct. Kades explains how disgorgement has been used, albeit sparingly, in cases brought against pharmaceutical companies and successfully prevented certain anticompetitive conduct across the industry. It also tends to speed up the litigation process, which saves costs and resources for the Federal Trade Commission. As such, Kades writes, the Supreme Court’s ruling benefits big companies that cause the most harm and will have a troubling impact on antitrust enforcement, unless Congress takes action to reestablish the FTC authority.

- Conversely, Andrew I. Gavil takes a glass-half-full approach, arguing that the Supreme Court’s ruling may end up opening the door to broader applications of the U.S. antitrust laws. Gavil highlights the textualist nature of the Court’s decision and how it could be applied to the antitrust laws, particularly the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914. He gives a brief background on the Clayton Act and its relationship to the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, before turning to an analysis of the law and its reach through a textualist lens.

Each month, Equitable Growth highlights scholars working to understand how inequality affects economic growth in a series called Expert Focus. This month, Adrian Narayan and David Mitchell look at a group of academic researchers who joined the Biden administration to advance evidence-backed policy ideas to combat inequality and ensure strong, stable growth for all Americans. Narayan and Mitchell emphasize not only that Equitable Growth staff joined various agencies in the executive branch, but also how many academic network members, contributors, and speakers from previous Equitable Growth events decided to being their diverse experience and expertise to the administration.

The National Bureau of Economic Research is now more than halfway through its summer institute, an annual 3-week conference featuring discussions and paper presentations on specific subfields of economics, including wealth taxation and tax evasion, market structure and competition, and labor market inequalities. Equitable Growth compiled a list of paper abstracts that caught our attention throughout the second week, including research from our grantee network and members of our Steering Committee and Research Advisory Board. For highlights from the first week of the NBER Summer Institute 2021, click here. For coverage of the third and final week, be sure to check back on Monday, August 2.

Check out Brad DeLong’s most recent installment of Worthy Reads, where he provides summaries and analysis of must-read content from Equitable Growth and elsewhere.

Links from around the web

New analysis reveals that states that cut expanded federal Unemployment Insurance benefits early are not actually experiencing a hiring boom. States that did not cut UI payments had the same pace of hiring as those that did cut them early, write The Washington Post’s Heather Long and Andrew Van Dam. Interestingly, though, states that did cut benefits are seeing changes in who is getting hired, with fewer teenagers securing employment and higher rates of hiring for those workers ages 25 and older. The analysis focuses on small restaurants and hospitality businesses, which, Long and Van Dam note, will probably face extended hiring challenges. This is largely because of the ongoing health threat posed by the coronavirus, continuing caregiving needs, and the prevalence of workers leaving their pre-pandemic industries in search of new opportunities. These three trends are likely more to blame for the hiring slump in hospitality than extended UI benefits, according to several experts that Long and Van Dam interview.

Coronavirus relief programs will cut the U.S. poverty rate almost in half this year, compared to pre-pandemic levels, with the number of poor Americans set to fall by nearly 20 million. The country has never cut poverty so rapidly before, writes The New York Times’ Jason DeParle. This is all the more impressive considering the economy has more than 6 million fewer jobs now than it did before the pandemic and ensuing recession. But, DeParle continues, with many programs either already ended or set to expire soon, many of the families who have benefitted may find themselves back in poverty, or near the poverty line. DeParle tells the story of a few such families and their struggles amid the coronavirus pandemic.

President Joe Biden’s recent executive order designed to increase competition and reduce market concentration, along with several pieces of bipartisan antitrust legislation in Congress, suggest that U.S. antitrust regulators are focused on addressing the problem of “bigness.” But, Molly Wood asks in The Atlantic, why is Microsoft Corp. often left of the list of Big Tech companies—Amazon.com Inc., Apple inc., Facebook Inc., and Alphabet Inc.’s Google unit—that typically get the most scrutiny for their anticompetitive behavior? Microsoft, as big as the others, has largely escaped run-ins with the antitrust laws since its high-profile lawsuit in the 1990s. And technically, Wood points out, it’s not illegal under these laws to be big, or even to be a monopoly, unless the company uses its position to drown out competition or charge unfairly high prices. Wood examines the circumstances surrounding the lack of antitrust cases brought against Microsoft. She ultimately makes the case that it should be the test of the Biden administration and antitrust regulators’ will to increase competition, break up tech companies, and scrutinize acquisitions: “If bigness alone is the problem, Microsoft is the truest test of all.”

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Competitive Edge: Congress needs to restore the Federal Trade Commission’s authority to seek monetary remedies when companies break the law,” by Michael Kades.