Weekend reading: Addressing earnings inequality across the U.S. labor force edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

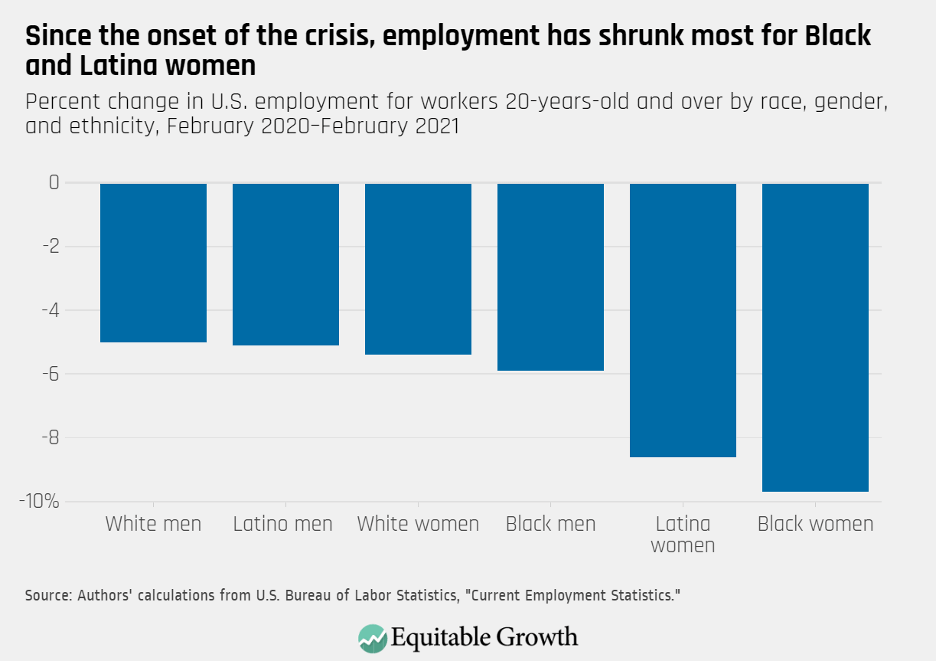

This Women’s History Month marks 1 year since COVID-19 restrictions began in many U.S. cities and states, and thus the unofficial start of what many have dubbed the “shecession,” thanks to the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus recession on women workers. Delaney Crampton looks at recent research on women’s longstanding challenges in the U.S. economy due to employer monopsony power, the child care crisis, and pay equity. These issues affect women of color in particular, both historically and today. One year into the pandemic, women workers of color are still experiencing higher rates of unemployment and loss of earnings than other workers. Crampton summarizes a series of studies showing how women, and especially women of color, face significant hurdles in the labor market and why each of these crises—earnings inequality, lack of access to child care, and monopsony power—must be addressed.

This week also marked Asian American and Pacific Islander Women’s Equal Pay Day, the day in 2021 until which, on average, Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander women have to work, from the start of 2020, to earn as much as White, non-Latino men earned in 2020 alone. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming explain the data on this 15-cent wage gap, particularly amid the coronavirus recession, due to the over-representation of AANHPI men and women among front-line workers. Though the wage divide between White, non-Latino men and AANHPI women narrowed significantly over the past two decades, Bahn and Sanchez Cumming write, many Asian American women continue to face pay discrimination and other obstacles in the labor market. A challenge for economic researchers lies in the lack of data that are disaggregated among the many subgroups of workers and families within the AANHPI community—an issue that Bahn and Sanchez Cumming argue is necessary to address in order to ensure that policymakers can target programs and aid more effectively.

Earnings inequality is a big driver of economic inequality in the United States. Recent research shows, however, that it’s not only what you do but also where you work that matters. Increasing alignment of earnings in occupations and at workplaces is making inequality worse. Nathan Wilmers and Clem Aeppli detail the findings in their new working paper, which showcases the importance of studying earnings inequality at workplaces and in occupations together, as high-paying occupations are increasingly clustered at high-paying workplaces and low-paying jobs at low-paying workplaces. This means higher-paid workers are earning increasingly more, while low-paid workers earn even less—resulting in “worse earnings inequality than either between-occupation or between-workplace variation would create by themselves,” the co-authors conclude. They then explain the implications for policymaking to address these two types of earnings inequality together rather than in silos.

Workers in the United States who typically experience lower earnings than they should are gig workers. Kathryn Zickuhr details how ride-hail drivers, such as those who work for Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc., are often misclassified as independent contractors by their employers in order for those companies to avoid paying them a minimum wage or providing full-time worker benefits such as health insurance or paid sick leave. Zickuhr then looks at a recent study of New York City’s 2019 pay standard for gig workers, describing how it increased the average hourly earnings of ride-hail drivers to be more in line with the city’s $15 minimum hourly wage. But, she notes, misclassification deprives these workers of more than wages. While the pay standard did effectively boost pay, updating labor laws to prevent misclassification and ensure worker protections would better address the lack of economic security and benefits that gig workers experience.

Every month, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases data on hiring, firing, and other labor market flows from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, better known as JOLTS. This week, the BLS released the latest data for January 2021. Bahn and Sanchez Cumming put together four graphics highlighting trends in the data.

Links from around the web

One way to address the vast racial wealth divide between Black and White Americans in the United States is reparations—and one Chicago suburb is set to become the first city to financially compensate its Black residents for centuries of wealth and opportunity gaps resulting from enslavement, systemic racism, and discrimination. NBC News’ Safia Samee Ali reports the latest news on a reparations program in Evanston, Illinois, a program approved in 2019 and funded via community donations and revenue from a 3 percent tax on recreational marijuana sales. Critics are debating the legislation from several sides, but proponents argue that it’s an historic model that could be used in cities across the United States—at least until a federal reparations program is enacted. The city council is expected to vote in the coming weeks on a plan to release the first $400,000 to address housing needs.

President Joe Biden this week signed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan and with it, may have started the second War on Poverty, writes Vox’s Dylan Matthews. The COVID-19 relief bill includes some of the most far-reaching anti-poverty policies in decades, Matthews explains, harkening back to former President Lyndon B. Johnson’s collection of government programs to combat U.S. poverty in the 1960s. The parallels between the two presidents and their two anti-poverty plans are clear, and while the American Rescue Plan may not be as impactful, it is estimated that poverty will fall by one-third overall, with child poverty cut in half, as a result of the bill’s enactment. Matthews runs through the various policies included in President Biden’s plan and the effects they’ll likely have on poverty, then turns to policies the president can push for in future legislation to continue waging this war on poverty now that the American Rescue Plan has been signed.

The passage of the American Rescue Plan also signals a shift in lawmakers’ willingness to use their authority to set the U.S. economy on the path to recovery, writes The New York Times’ Neil Irwin in The Upshot. The coronavirus recession shows that leaders from both parties are willing to borrow and spend money to “extract the nation from economic crises … [a power] they ceded for much of the last four decades.” This change stands in direct contrast to the response to the Great Recession of 2007–2009, Irwin argues, which was largely dealt with by the Federal Reserve—an entity with much more limited tools to address recessions. And, if successful, the American Rescue Plan could be a blueprint for how the U.S. government responds to future crises.

While the American Rescue Plan, on its face, is a coronavirus relief package, it also will have an impact on U.S. climate policy, writes The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer. Of course, it isn’t a sweeping, climate change-specific bill, but by reviving many institutions that are central to addressing climate change that have been battered by the pandemic, it is part and parcel of the Biden administration’s overall climate agenda. Meyer briefly examines the various programs in the bill that will impact U.S. climate policy, from boosting public transit agencies to supporting state and local governments, and shows how this legislation has begun to shift political perspectives in such a way that opens the door for fighting climate change directly.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Women’s History Month: Systemic gender discrimination continues to harm working women amid the coronavirus recession” by Delaney Crampton.