U.S. jobs report: Amid robust employment gains in May policymakers need to consider the future direction of demand-driven employment growth across industries

The recovery in U.S. employment picked up some steam last month. According to the latest Employment Situation Summary by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. economy in May gained 559,000 jobs, compared to the unexpectedly low 278,000 jobs added in April. While still 3.3 percentage points below its pre-coronavirus recession level, the share of adults between the ages of 25 and 54 with a job—the prime-age employment-to-population-ratio—rose from 76.9 to 77.1. But the share of adults either employed or actively looking for a job declined slightly, with the labor force participation rate going from 61.7 percent in April to 61.6 percent in May. Troublingly, the U.S. labor force participation rate remains at roughly the same level as in June of last year.

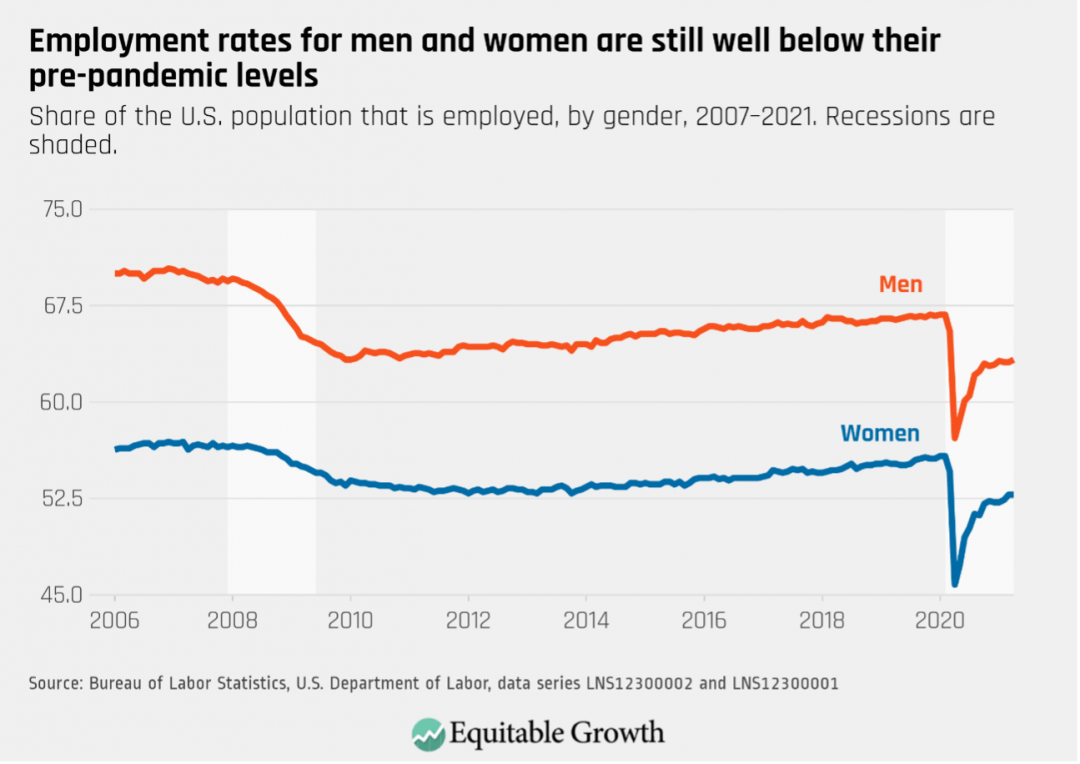

A closer look at the report shows how different groups of workers are experiencing the U.S. labor market. The jobless rate for Black workers fell from 9.7 percent to 9.1 percent between mid-April and mid-May, but continues to be higher than for any major racial or ethnic group. For Latinx workers the unemployment rate now stands at 7.3 percent, for Asian American workers at 5.5 percent, and for White workers at 5.1 percent. After remaining flat between March and April, the share of women who are employed climbed from 52.8 percent to 53.1 percent between April and May. For men that same number rose from 63.3 percent to 63.4 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

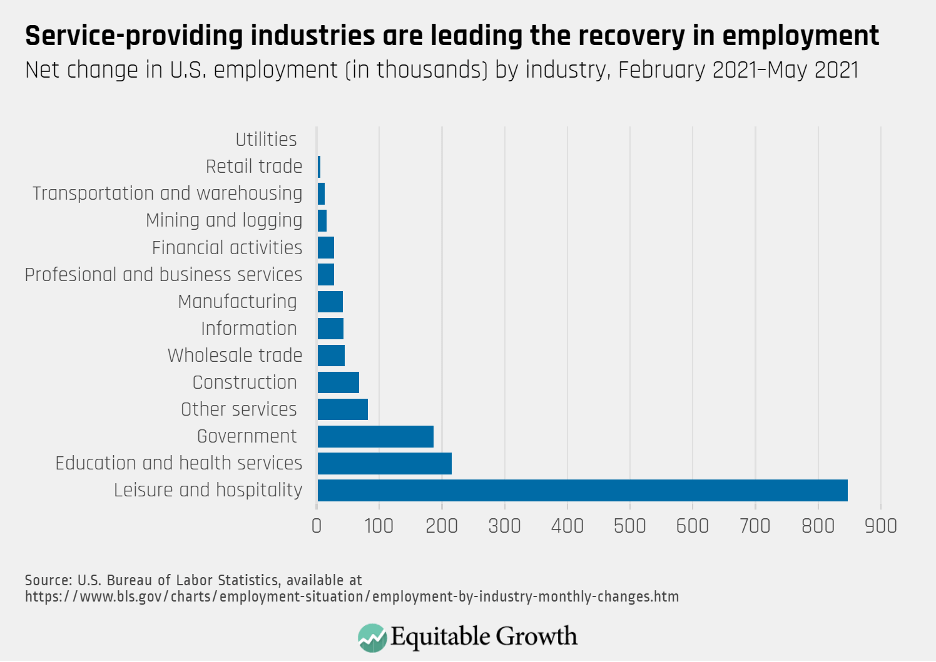

In addition, over the past few months net job gains have been especially robust in service-providing industries as the U.S. labor market makes uneven progress toward a recovery. Between February and May, the leisure and hospitality industry recovered 847,000 jobs—more than any other major sector. It was followed by education and health services, which added 216,000 jobs. Other services—an industry that includes subsectors such as personal care and repair services— added 82,000 jobs. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

As industries that experienced the brunt of the economic shock gain some ground, it is worth understanding how the economic recovery from this recession could be different from previous ones in order to best design and implement policies that will foster a more inclusive and thus more robust recovery.

At their onset, economic downturns tend to be hardest on goods-producing sectors such as manufacturing, since consumption of durable goods tends to be especially sensitive to fluctuations in the business cycle. In other words, in bad times consumers tend to cut back on their spending of products such as cars and furniture more so than on food or services related to health or education.

Yet the coronavirus recession hit service-providing industries early and hard. This turmoil roiled groups of workers who are not usually among the most exposed to job losses at the start of recessions—namely women of color who suffered the deepest employment losses in part due to their overrepresentation in service-sector jobs. In addition, the concentration of the shock in services industries could have consequences for the progression of economic recovery based on demand effects.

Martin Bejara at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Christian Wolf at the University of Chicago, for example, propose that all else being equal, recessions driven by a drop in demand for services are followed by weaker recoveries than recessions driven by a shortfall in demand for durable goods. The reason is that as economic conditions improve consumers are more likely to go ahead with their plans to purchase, say, household appliances, than make up all their missing spending on services such as haircuts or dinning out. In the context of the continuing pandemic, this adds even more uncertainty to the U.S. economic outlook.

While there may be limits how much spending on services will increase to make up for the drop in demand as the economy begins to recover, some economists argue that as COVID-19 vaccination rates increase and more businesses reopen, pent-up demand for travel, entertainment, and postponed health care are helping drive a bounce back. In addition, research shows that policies such as expanded Unemployment Insurance benefits allowed many workers to keep up their spending and protected the overall economy from a shortfall in demand for goods and services—a finding that highlights the need to maintain enhancements to jobless benefits and address racial disparities in benefit take-up.

The upshot: Directing stimulus to those hardest hit in recessions can reduce the overall shock of a downturn, and Unemployment Insurance is an effective tool for targeted aid to those who have lost income.

Conclusion

Between February and April of last year the U.S. economy lost more than 22 million jobs. As of last month, the labor market continues to be at a 7.6 million deficit with respect to February 2020—a deficit that is even larger when comparing it to where the labor market would be absent the recession. In addition, there is evidence that there is more slack in the U.S. labor market than top-line statistics suggest, with new research by economists at the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank finding that without accounting for the unique circumstances accompanying this recession, the metrics most often used to measure the health of the U.S. economy could be painting an overtly optimistic picture.

Despite evidence that millions of workers are still struggling, largely overstated fears over potential labor shortages led many state governors to prematurely opt-out of federal Unemployment Insurance programs. As of the release of this column, 25 states have decided to slash the additional $300 in weekly jobless benefits before they expire on Labor Day in September. Most of these states are also withdrawing from the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation program, which extends the number of weeks workers can claim benefits for, and from the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, which also expires on Labor Day, meaning that many workers who are self-employed, cannot work due to COVID-19-related reasons, or have limited work histories will stop receiving UI benefits altogether.

This is all why policymakers and analysts should be cautious when claiming the U.S. economy has fully bounced back—overstating the health of the labor market can lead to policies that hold back a strong and equitable recovery.