To combat rising U.S. prescription drug prices, let’s try competition

Michael Kades, Equitable Growth’s Director of Markets and Competition Policy, will testify on March 7 at a hearing of the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law. At the hearing, entitled “Diagnosing the Problem: Exploring the Effects of Consolidation and Anticompetitive Conduct in Health Care Markets,” Kades will discuss the competition issues in the prescription drug marketplace raised in this article.

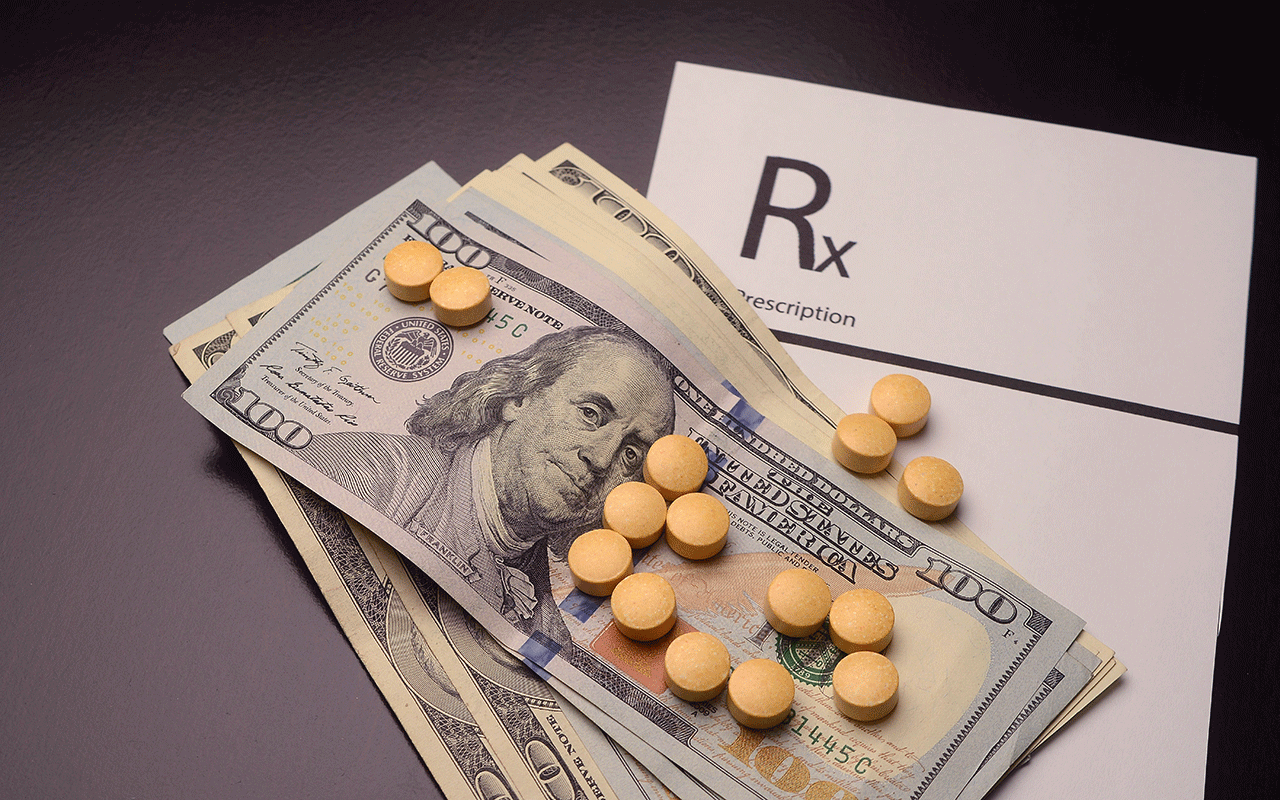

The rising cost of prescription drugs in the United States is now a “weather” issue—everybody talks about it. The difference is you can’t change today’s weather, but we can do something about drug prices. And competition is an important part of the answer.

Since 1960, overall national health expenditures have risen as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product from 5 percent to around 18 percent, and drug prices have generally risen right along with them. And the future does not look good. The American Academy of Actuaries notes that cost projections by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services cite spending for retail prescription drugs as the consistently fastest growth health category over the next decade.

High prices mean that millions of Americans struggle to pay for their medications. Too many either don’t take a needed drug or don’t take the recommended amount, simply because they can’t afford it. A 2018 survey by GoodRx—a firm that tracks drug prices and offers drug coupons—found that fully one-third of Americans had in the previous 12 months skipped filling a prescription at least once due to cost. Obviously, this can affect health outcomes. And it is not acceptable. It’s time to inject some serious competition into the U.S. prescription drug industry.

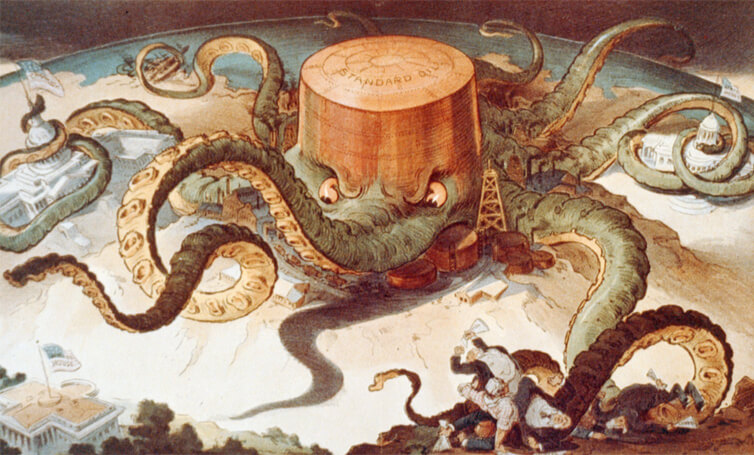

But first, let’s look at the variety of problems with anti-competitive practices engaged in by U.S. pharmaceutical companies. Take ViroPharma Inc. When faced with the possibility that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration would approve generic versions of its Vancocin product (a drug to treat a potentially life-threatening gastrointestinal infection), the company filed 43 petitions to delay or prevent generic approval. Although none were successful on the merits, it took years before the FDA approved any generic competitors. The Federal Trade Commission alleged the strategy increased costs by hundreds of millions of dollars.

Or consider, Cephalon Inc. When it faced four potential generic competitors for its wakefulness drug, Provigil, it paid them to stay off the market until 2012 as part of a patent settlement. Afterwards, its CEO boasted, “We were able to get six more years of patent protection. That’s $4 billion in sales that no one expected,” which meant six years of less competition for consumers.

Another example is Revlimid, a chemotherapy drug manufactured by Celgene Corporation. It can sell for more than $750 per capsule (costing cancer patients some $20,000 a month). Mylan N.V. sought to manufacture a generic version, but Celgene has prevented Mylan from obtaining the samples of Celgene’s product, citing the dangerous side effects of the drug. Without those samples, Mylan cannot conduct the testing that the Food and Drug Administration requires to approve a generic product.

The relatively new and very promising category of drugs known as biologics are magnifying this cost issue. According to the FDA, these products include “vaccines, blood and blood components, allergenics, somatic cells, gene therapy, tissues, and recombinant therapeutic proteins.” Biologics “can be composed of sugars, proteins, or nucleic acids or complex combinations of these substances, or may be living entities such as cells and tissues,” according to the FDA. “Biologics are isolated from a variety of natural sources—human, animal, or microorganism—and may be produced by biotechnology methods and other cutting-edge technologies.”

Biologics have already had a major impact on the treatment of some diseases. But they are very expensive to develop. And their increasing role in healthcare will probably accelerate overall cost increases. Indeed, those who try to justify high U.S. drug prices frequently rely on the cost of research and development of biologics and other prescription drugs to make their case. It requires a lot of money to discover and develop drugs, the theory goes, and when they succeed, the large profits guaranteed from patenting these new drugs are ostensibly plowed back into research and innovation to produce new and better drugs.

At first glance, this seems like a very strong argument, except that the theory does not always explain the reality. Robin C. Feldman of California Hastings College of the Law examined drug development over a 10-year period and found that “rather than creating new medicines, pharmaceutical companies are recycling and repurposing old ones.” Her report found that “on average, 78 percent of the drugs associated with new patents [between 2005 and 2015] were not new drugs coming on the market, but existing drugs.”

Not surprisingly, pharmaceutical companies were especially likely to engage in such practices to extend patents on their current blockbuster drugs. Feldman found that companies effectively extended the patents on about 80 percent of the 100 best-selling medications during this period. In other words, a lot of those profits are being plowed into ways of maintaining those profits, not making true medical advances.

The pharmaceutical industry is a unique market with unique rules. The legal structure has been designed with the intent of encouraging an adequate supply of medicines and continuing innovation in the search for treatments and cures while also ensuring a degree of competition to produce market efficiency to keep prices in check. Yet there are serious problems in the system. The biggest is the prices that help keep insurance premiums high and, for too many people, block access to drugs they need to ameliorate suffering or even save their lives.

There is already a well-tested tool for moderating prescription drug expenditures: Competition. The Government Accountability Office in 2018 cited comprehensive studies by IMS Health, a healthcare information services company, of the generics industry that found total savings to the health system from the use of generics in the years 1999-2010 to be more that $1 trillion. As most of us have experienced, generics have become ubiquitous at the pharmacist’s counter (as well as on grocery and drugstore shelves) since the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, more commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, established a streamlined process for their approval. It is well understood how this law promoted price competition, but the threat of competition also spurred innovation.

The law provided drug manufacturers unique protections from competition. Drug companies get their patents extended based on the time it takes the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to approve the product, and they receive certain other exclusivities that prevent competition. On the other side of the ledger, the Hatch-Waxman Act creates an abbreviated approval process for generic versions of the drug—products that are identical to the original but usually have a much lower price tag.

In fact, according to research by the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics (conducted with support from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America), the price of medicines declined on average by 51 percent in the first year and 57 percent in the second year following the introduction of generics between 2002 and 2014.

But the talents of pharmaceutical companies are not limited to developing drugs to treat disease. These firms also excel at creating schemes to fatten their profits by keeping the revenues flowing from their most valuable drugs even after their patents expire. They create and patent “new” drugs that are slight variants on the original drugs, or they use several other means to effectively extend the original patent in ways that are entirely, or at least arguably, legal.

A similar dynamic is occurring in the realm of biologics. Drugs that are interchangeable with biologics, known as biosimilars, are being developed and, like generics, offer the possibility of effective drugs at lower prices. But there is real concern that barriers to competition may snuff out these alternatives. It is worth noting that the European Union approved its first biosimilar in 2006, but the FDA did not approve a biosimilar until 2015. Today, according to NPR, Europeans have access to some 50 biosimilars, while only six have been approved in the United States.

While sometimes ingenious, the tactics used by manufacturers of brand-name drugs, as well as biologics, can be costly to these firms. But the enormous profits the companies are protecting make those expenditures worthwhile. All these practices can be clearly restricted or outlawed by legislation—if Congress and the Trump administration choose to address them, or, in some instances, if federal courts reconsider their current framework for considering antitrust issues.

What are the most common tactics employed by the U.S. pharmaceutical industry to block competition? And what can be done to address them? Here are five major problems and suggested remedies.

Drugs firms make testing impossible, so guarantee access to the original drugs

To gain approval for a generic, manufacturers must test their product against the original, so they need to purchase the branded drug in bulk from wholesalers. However, if the Food and Drug Administration brands a medication as “dangerous,” then it cannot be sold through wholesalers. Consequently, one tactic for blocking a generic is to convince the FDA to declare the original drug dangerous and then refuse to sell the would-be generic manufacturer enough of the medication to test it. Some companies are taking the position that, even absent the FDA’s declaring a drug is dangerous, they can unilaterally prevent the sale of the product to potential competitors.

The FDA is making efforts to adjust its processes to make it more difficult for pharmaceutical companies to gain a “dangerous” label for their products. But legislation could simply guarantee the ability of a generics company to purchase the quantity of a branded product it needs to test its own generic version by making it a condition of drug approval or giving generics manufacturers petition rights.

“Pay-for-delay” patent settlements block cost-saving competition, so prevent the practice

Another tactic used by brand-name companies is to sue a generic manufacturer seeking to sell a generic version of its product for alleged patent infringement and then settle the case by paying the manufacturer to delay bringing the generic to market.

Patent settlements are sometimes challenged successfully by the FTC. Yet these types of cases can take years to settle—one recent case took more than a decade—and there are too many instances where the tactic succeeds. Legislation establishing that patent settlements are presumptively anticompetitive could effectively neuter this tactic for undermining competition.

“Product hopping” improperly extends patent protection, so the courts and enforcers should be more skeptical of the practice

When the patent on a lucrative drug approaches termination, companies sometimes seek a new patent by making relatively insignificant changes in the original product. When these minor reformulations are successful, companies discontinue the original, doctors switch patients’ prescriptions to the newly patent-protected version, and the market for generics for a popular medication disappears.

This tactic can be challenged, but the courts often do not recognize it. Addressing product hopping requires a change in the framework the courts use to focus on whether a replacement drug is primarily an effort to effectively extend the patent on the original product.

Exclusionary rebates hide the true cost of drugs and can exclude competitors, so courts and enforcers should be more skeptical of the practice

Prescription benefit managers are supposed to, and often do, push down prescription drug prices for the insurers (and therefore for patients). Yet the system of rebates by which discounts are effected and by which prescription benefit management companies make a profit, as well as the opacity of transactions between these firms and pharmaceutical companies, sometimes encourage prescription benefit managers to prefer more expensive drugs because they provide the highest rebates. This is of particular concern when it is used as a tactic to exclude biosimilar drugs. This practice when it prevents competition should violate the antitrust laws, but courts have been too lenient and should be tougher on the practice. The solution is more transparency in drug pricing.

Anti-competitive practices are lucrative, so enact stronger deterrence

The profits from delaying competition, for even a few months, can run into the billions of dollars. Absent strong deterrence, we can expect that some companies will see antitrust enforcement simply as the cost of doing business. But just last week, a federal court significantly limited the ability of the FTC to seek disgorgement (a remedy that deprives a defendant of its illegal profits) for past behavior. This ruling could affect any case in which the FTC challenges the conduct after its completion.

Congress can easily remedy this by clarifying that disgorgement and other monetary remedies are available for violations of the FTC Act. It could go even farther and give the FTC the ability to assess penalties for particularly blatant antitrust violations.

Bringing competition back to the fore in the U.S. pharmaceutical industry

None of these problems are insurmountable, and none of these solutions are a silver bullet. But each of the remedies together could unleash true competition by encouraging not only lower prices but also greater innovation. And these remedies, of course, are not the only steps that can be taken to control drug prices.

Senators Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and others have introduced legislation to permit individuals to purchase prescription drugs directly from Canada. This would provide another source of competition for U.S. drug makers. And Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) and Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D-TX) have proposed legislation to authorize the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate drug prices paid by Medicare.

But the proposals outlined in this article specifically recognize the role that legal enforcement and regulation by the FTC can play in ensuring competition for brand-name pharmaceuticals from generics, including biosimilars. Such competition benefits consumers, encourages innovation, and keeps the pharmaceutical companies honest. It’s how the system is supposed to work, and still can.