Taxing wealth by taxing investment income: An introduction to mark-to-market taxation

Overview

The sharp increase in U.S. wealth inequality in recent decades has spurred interest in increasing taxes on wealth. This issue brief introduces mark-to-market taxation, one approach to raising taxes on wealth by reforming the taxation of investment income.1 In a system of mark-to-market taxation, investors pay tax on the increase in the value of their investments each year rather than deferring tax until those investments are sold, as they do under current law. This issue brief first defines investment income and explains how mark-to-market taxation works. It then reviews the revenue potential of this approach to taxing investment income, explaining why a mark-to-market system can raise substantial revenues. Finally, it summarizes the distribution of the burden that would result, which would fall overwhelmingly on wealthy individuals.

Download FileTaxing wealth by taxing investment income: An introduction to mark-to-market taxation

What is investment income?

Investment income is income generated by wealth, including interest on a bond, dividends paid on a corporate stock, rents from real estate, and profits from a pass-through business such as a partnership. A pass-through business is one that “passes through” profits to its owners for tax purposes, who then pay income tax on those profits. In contrast, shareholders in a traditional C corporation do not pay tax on the corporation’s profits.

In addition to explicit payments and returns, investment income also includes increases in wealth that result from increases in the price of assets, such as increases in the price of stocks, bonds, real estate, or mutual fund shares. The income resulting from these price increases is known as a capital gain.2 For instance, if an investor buys $100,000 of corporate stock and then sells it 1 year later for $110,000, then that $10,000 of income is a capital gain. Some assets, such as bonds, tend to generate income mostly in explicit payments, while other assets, such as stocks, tend to generate more income in capital gains.

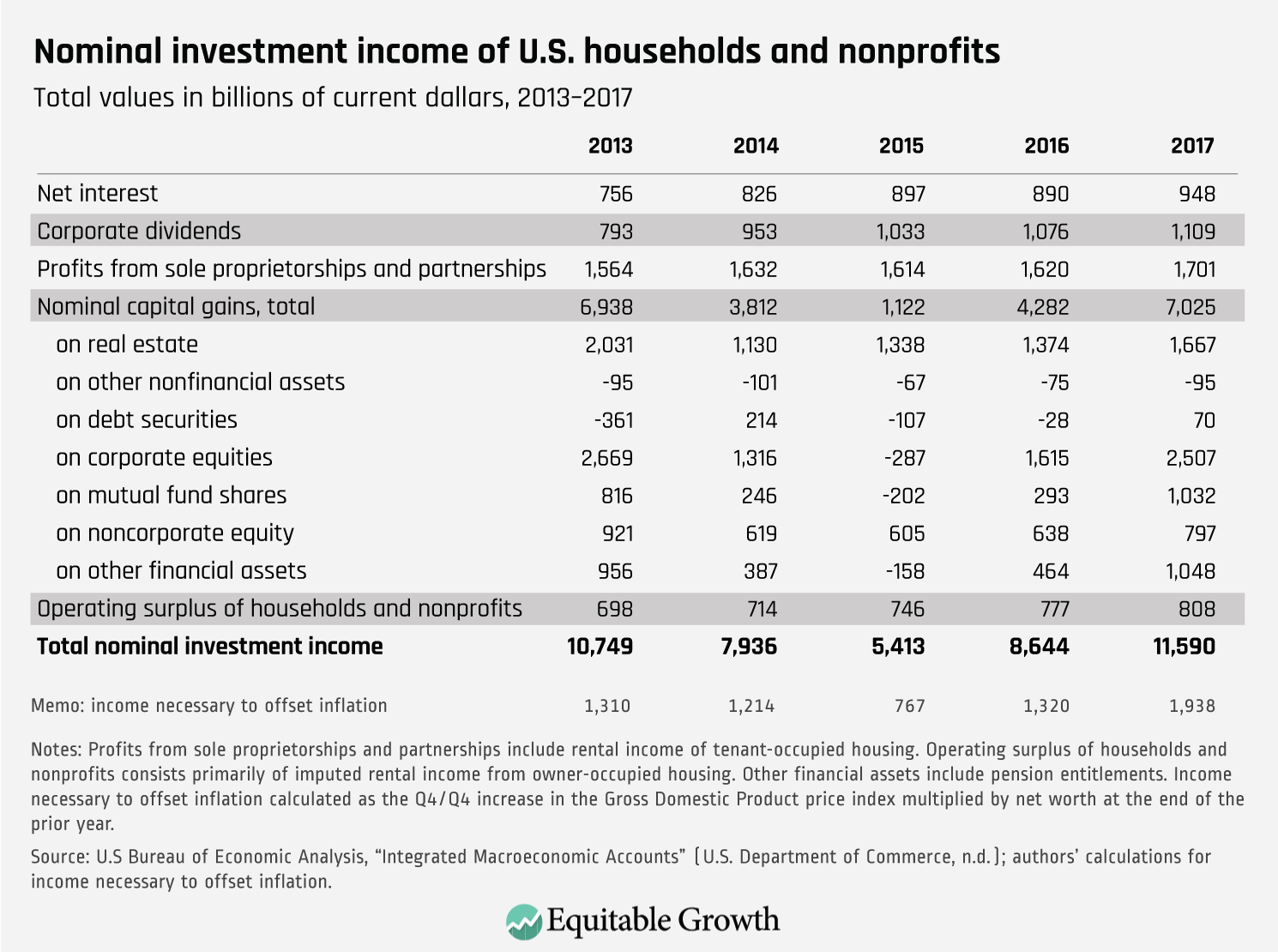

Capital gains are a key form of investment income for U.S. households. Since 2009, capital gains have added $3 trillion to investment income each year, on average. Capital gains are also a much more volatile form of income than interest, dividends, and profits from pass-through businesses. They are the source of large losses in some years and large gains in others. (See Table 1 for a breakdown of the investment income of U.S. households and nonprofits, as estimated in the U.S. Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts, from 2013 to 2017. A portion of the total investment income received offsets the reduction in purchasing power that results from inflation. An estimate of the income necessary to offset inflation in each year is also provided in the table.)

Table 1

How is investment income taxed in the United States today?

The taxation of investment income varies dramatically across different types of assets.

Interest payments, dividends from corporate stocks and mutual funds, and rents are taxed when earned. Dividends and distributions from pass-through businesses, such as partnerships and S corporations, are largely exempt from taxation. Instead, as noted above, the owners pay tax on the profits of these businesses as those profits are earned.

Notably, to measure income more accurately and prevent tax avoidance, U.S. tax law requires many taxpayers to measure interest and profits as they accrue, not when money changes hands. Under the rules for what’s known as “original issue discount,” for example, an investor who owns a bond that does not pay interest on an annual basis must include in their income each year a portion of the interest that will eventually be paid as if it had been paid that year. Similarly, large businesses must measure profits, for tax purposes, according to the principles of accrual accounting, meaning they measure income when it is earned, not when it is received.

Interest payments are taxed at the same rates that apply to wages and most other sources of income (up to a maximum rate of 40.8 percent).3 Rents and profits from pass-through businesses may be taxed at these rates or may be eligible for preferential tax rates introduced by the tax legislation enacted at the end of 2017 (up to a maximum rate of 33.4 percent). Dividends from corporate stock are generally eligible for an even more generous set of preferential rates (up to a maximum rate of 23.8 percent).

In contrast to the contemporaneous taxation of interest, dividends, and pass-through profits, capital gains and losses are taxed only when the gain or loss is realized, which generally means when the underlying asset is sold. The ability to delay paying tax on gains until an asset is sold is known as deferral. Suppose an investor purchases $10 million worth of shares in a nondividend-paying stock at the beginning of the year, holds them for 2 years, and then sells them for $12 million. The shares are worth $11 million at the end of the first year. The investor realizes no income and pays no tax on the investment in the first year and realizes $2 million of income and pays tax on that $2 million in the second year. In this example, the taxpayer has deferred $1 million of income from the first year into the second year. The computation of gains and losses in the tax code does not make any adjustments for inflation.

Capital gains on corporate stock held for 1 year or less (short-term gains) are taxed at the same rates applied to wages and other income (up to a maximum rate of 40.8 percent). Capital gains on corporate stock held for more than 1 year (long-term gains) are generally eligible for preferential rates (up to a maximum rate of 23.8 percent). Capital gains on other types of assets are subject to a variety of different rates. Collectibles, such as works of art, are taxed at a maximum rate of 31.8 percent, for example.

In addition to the complexity of the basic structure for taxing capital gains, additional preferences exist for certain types of gains. Any unrealized capital gains on assets held when a taxpayer dies are permanently exempt from taxation under a provision known as “step up in basis.” The basis of an asset is generally the cost of the investment in that asset, and the gain when sold is the sales proceeds less the basis. Under this provision, the basis for assets held at death is reset (stepped up) to the market value at death, which wipes out the gain for tax purposes. Another set of special rules allows taxpayers to swap one real estate asset for another similar asset—a so-called like-kind exchange—and defer the gain on the first asset until the second asset is sold.

Tax-advantaged pensions and retirement accounts also provide a substantially reduced rate of tax for investment income earned in these accounts. Contributions to pension funds and retirement accounts are limited under the law precisely because they offer this benefit. Owner-occupied housing is also tax preferred. Homeowners are not taxed on the implicit rent they pay themselves, and they may also exclude up to $250,000 ($500,000 for married couples) of capital gains on the sale of a primary residence.

The preferences for certain types of investment income, including the preferential rates, offer a direct benefit to investors. In addition, the complexity of these rules and the interactions between them open the door to a variety of tax avoidance strategies. Perhaps most notably, the realization system means that investors can delay paying taxes indefinitely by holding onto appreciated assets. They may be waiting for Congress to lower the capital gains rate or offer some other benefit, or simply holding the assets until they die, at which point the gains will be eliminated entirely through step up in basis when the assets are passed onto their heirs.

Taxpayers may also attempt to convert income that would be taxed at higher rates into capital gains so that it is eligible for the preferential rates. Owners of a closely held C corporation, for example, may pay themselves less in wages than they would absent tax considerations. This reduction in wages increases the value of the corporation, turning those wages into tax-preferred capital gains.4

What is mark-to-market taxation?

Mark-to-market taxation is an approach to taxing investment income under which any increase in the value of a taxpayer’s assets is included in income each year. In other words, taxable income includes the full value of capital gains in the year they accrue, whether the gain is realized or not. As a result, a mark-to-market system of taxation treats capital gains in the same way interest, rents, and profits from pass-through businesses are treated under current law. In essence, adopting a system of mark-to-market taxation means repealing deferral. The name mark-to-market taxation comes from accounting, in which valuing an asset at its market value is known as marking to market. This type of approach is also sometimes known as accrual taxation. Figure 1 below illustrates the tax treatment of (a) interest under current law, (b) capital gains under current law, and (c) capital gains under mark-to-market taxation.

Figure 1

Three key design choices for a system of mark-to-market taxation are (1) the set of assets covered by the system, (2) the rate of tax to apply, and (3) whether to adopt special rules for dealing with volatility. We briefly discuss each of these choices.

First, under a mark-to-market system, taxpayers include capital gains in their income each year. This requires an annual valuation for each covered asset. The primary advantage of applying mark-to-market accounting to all assets is the reduction in tax avoidance opportunities resulting from a single, uniform system of taxation. Yet applying mark-to-market taxation only to a limited set of assets that are easier to value (potentially in combination with a deferral charge, as described below) may make compliance and administration easier.

Second, in principle, investment income could be taxed on a mark-to-market basis at any tax rate. But proposals to adopt mark-to-market taxation are often combined with proposals to raise the tax rate on capital gains. Applying the same rate to capital gains as to wages and other sources of income offers potential advantages by eliminating avoidance strategies that seek to convert income from the more heavily taxed type to the more lightly taxed type. In addition, one reason for adopting mark-to-market taxation is that it reduces the effectiveness of strategies used to avoid paying taxes. As a result, raising tax rates on capital gains raises more revenue if a mark-to-market system has already been adopted (or is adopted at the same time) than it would if enacted on its own.

Lastly, as noted above, capital gains are a more volatile source of income than interest and dividends. In some years, capital losses exceed capital gains. Thus, the treatment of losses under a mark-to-market system can be important. A more generous approach would allow losses to offset any other sources of income in the current year. A more conservative approach would allow unlimited loss carryforwards, meaning that a loss in the current year can be deducted against investment income in any future year but cannot offset noninvestment income in the current year. In an alternative scenario, taxpayers might include only a portion of their gains and losses in income each year, effectively implementing a form of income averaging.

If a comprehensive system of mark-to-market taxation is enacted, then there would be no unrealized gains at death going forward, because gains will have been taxed on an annual basis, including in the year the person dies. However, unless the system applies to gains accrued prior to enactment, there would still be unrealized gains on existing investments. Thus, proposals for mark-to-market taxation often also tax gains at death or when assets are given away—effectively repealing step up in basis—to ensure equal treatment across generations and raise additional revenue. Including taxation of gains at death or gift becomes even more important if the system exempts certain taxpayers, as discussed in more detail below.

Though not an essential feature of mark-to-market taxation, adopting a system of mark-to-market taxation also offers an opportunity to address other weaknesses of the tax code. Measures to limit the balances accumulated in tax-preferred retirement accounts, such as mandatory distributions for account balances above a certain threshold, and additional limitations on the capital gains exclusion for home sales would fit naturally within the context of a proposal for mark-to-market taxation of capital gains.5

What is a deferral (or lookback) charge?

A deferral (or lookback) charge is an additional tax payment imposed when an asset is sold after being held for more than 1 year to account for the fact that the gains on the asset were not taxed on an annual basis—in other words, that taxes have been deferred. Deferral charges are an alternative approach to limiting or eliminating the tax benefit of deferral, while still relying on realization as the trigger for tax liability. The primary advantage of a deferral charge system, relative to a mark-to-market system, is that it avoids the need to value assets on an annual basis, which may be difficult in certain cases.

Some proposals for mark-to-market taxation combine mark-to-market taxation of certain assets with deferral charges for other assets.6 In general, the mark-to-market system is applied to assets for which independent valuations are more readily available, such as a stock traded on a public exchange, and deferral charges are used for assets for which an independent valuation may not be as readily available, such as a privately owned business. These approaches aim to balance competing goals in designing the system. A mark-to-market system requires valuations for hard-to-value assets, while a deferral charge system creates opportunities for tax avoidance through exploiting differences in the tax resulting from the deferral charge and the tax that would have resulted from annual taxation of accrued gains and losses.

A variety of structures for deferral charges have been proposed in the academic literature.7 Under one benchmark approach, the gain on an asset when sold is allocated in equal dollar amounts to each year between purchase and sale, the tax is computed on the income assigned to each year at the rate applicable in that year, and the unpaid taxes are accumulated with interest to compute the tax due. A closely related approach allocates the gain over the course of the investment’s lifetime assuming a constant rate of return rather than a constant dollar increase in value each year.

In addition, under a deferral charge system, unrealized gains would be deemed realized at death or when given away. Thus, all gains would eventually be taxed whether the assets are sold or not.

How could a mark-to-market system exempt middle-class taxpayers?

Mark-to-market taxation could be adopted as the universal approach to taxing investment income. Current proposals set forth by U.S. policymakers, however, have tended to apply the system only to wealthy taxpayers. Two approaches policymakers have suggested they might use for this purpose are a lifetime exemption on gains and an asset-based threshold for applying the tax.

Under a lifetime exemption approach, taxpayers would compute income under the mark-to-market system annually but would not pay tax on any mark-to-market gains or losses until they reach a cumulative amount of gains, such as $500,000, over their lifetime. This exemption could be used against mark-to-market gains, the interest portion of a deferral charge, and taxation of gains at death or when given away. But, under this approach, the exemption could not be applied against taxes due based on realized gains. Under the asset-based approach, taxpayers would only be covered by the mark-to-market system if their assets exceed a stated amount, such as $2 million.

A major difference between the asset-based approach and the lifetime exemption approach is that under the asset-based approach, taxpayers would enter and exit the mark-to-market regime multiple times if the value of their assets fluctuates. However, under the lifetime exemption approach, taxpayers are outside the regime until they have enough gains to be inside the regime and then remain inside the regime.

How much revenue could this type of tax reform raise?

The revenue potential of reforms to the taxation of investment income in the United States is large. Under current law, long-term capital gains and dividends are taxed at a 40 percent discount, relative to ordinary income. Moreover, tax planning strategies that take advantage of deferral, step up in basis, and other preferences for investment income mean that much investment income simply does not appear on tax returns at all.

Estimates of the revenue raised by reforms to the taxation of investment income are uncertain, as they depend on both the detailed specification of the tax and assumptions about how families would respond to the tax. But previous estimates suggest that mark-to-market reforms that also apply the tax rates on wage income to capital gains and dividends could easily raise $1 trillion over the next decade—and potentially much more, depending on how widely the higher tax rates are applied and what accompanying reforms are included.8

The revenue potential from increasing the capital gains tax rate in isolation is likely much smaller. The ease of tax avoidance under current law, such as the ready opportunity to defer tax by not selling assets and potentially avoid tax entirely through step up in basis—all while simply borrowing against these same assets to finance any spending—means that taxpayers may substantially reduce realizations in response to an increase in the capital gains rate.

A recent Congressional Research Service analysis, for example, suggests that taxpayers might avoid as much as 50 percent of the tax liability that would otherwise result from a 5 percentage point increase in the capital gains rate through avoidance.9 The report also highlights that some analysts might conclude that an even higher share of revenue would be lost through avoidance. Robust reforms to the tax base such as those discussed in this brief, however, would sharply limit these avoidance strategies and yield much higher revenues.

Who would bear the burden of a mark-to-market reform?

Reforms to the taxation of investment income such as those described above would be highly progressive. The economic incidence of these taxes—meaning the economic burden of the taxes, which is distinct from the legal obligation to pay them—would lie primarily on the owners of wealth.10

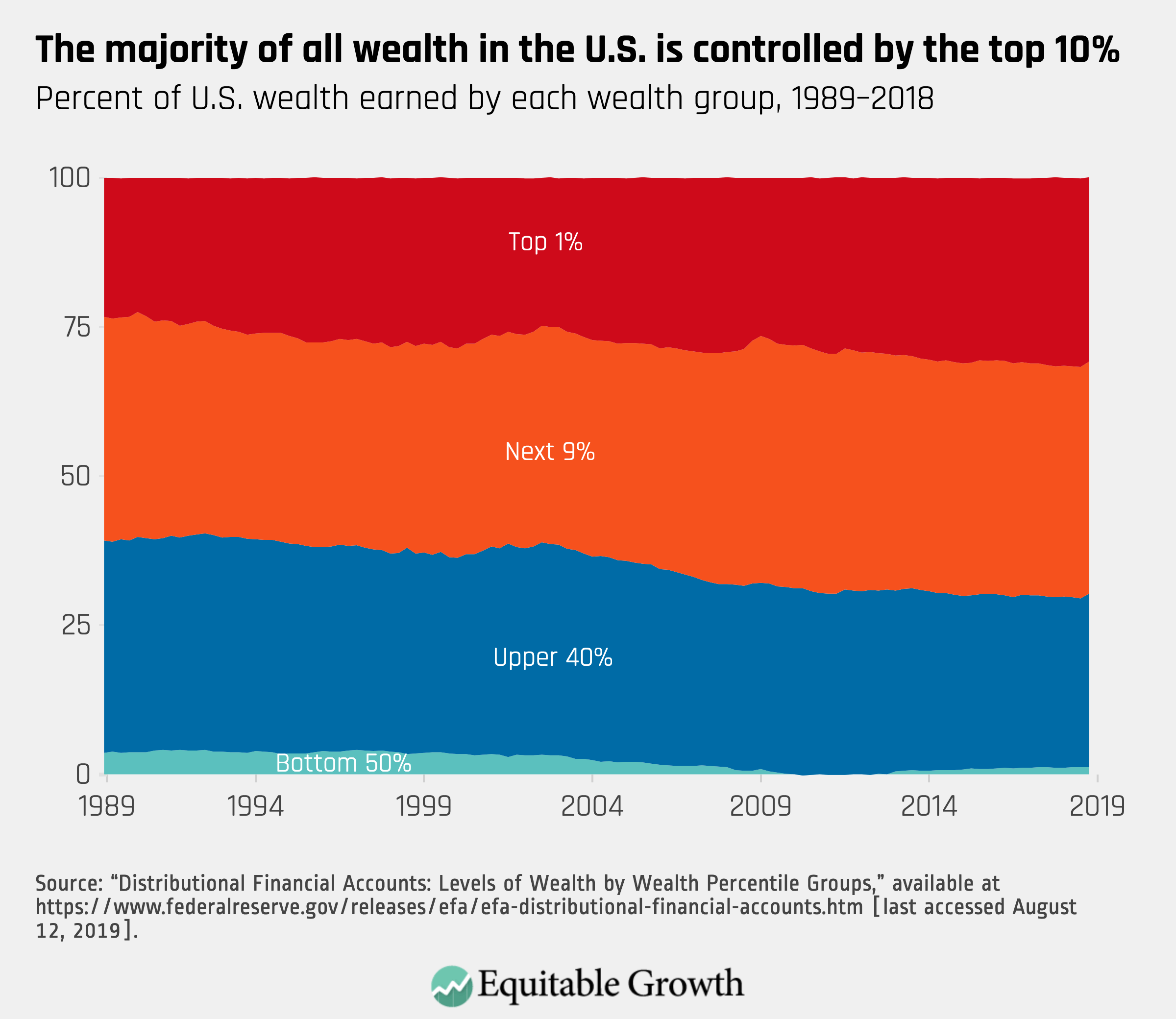

Wealth ownership in the United States is highly unequal. The wealthiest 1 percent of families holds 31 percent of all wealth, and the wealthiest 10 percent holds 70 percent of all wealth.11 (See Figure 2.) If policymakers include an exemption in the design of a mark-to-market system, the burden of the tax would be limited almost exclusively to high-wealth families.

Figure 2

Why might policymakers adopt mark-to-market taxation?

Reforms to the taxation of investment income could raise substantial revenues from the wealthiest families. The highest-income 1 percent of families receives 75 percent of the benefit of the preferential rates for capital gains and dividends under current law. Moreover, adopting a mark-to-market system would be a relatively efficient way to raise revenues, as the current system of taxing investment income allows wealthy taxpayers to avoid paying taxes by taking advantage of deferral, step up in basis, and other tax preferences. A mark-to-market system would scale back or eliminate these preferences and thus sharply reduce tax avoidance. Policymakers looking for a progressive tax instrument that raises substantial revenues would find mark-to-market taxation an appealing option.

End Notes

1. A previous brief introduced net worth taxes. See Greg Leiserson, “Wealth Taxation: An Introduction to Net Worth Taxes and How One Might Work in the United States” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019). See also Greg Leiserson, Raksha Kopparam, and Will McGrew, “Net Worth Taxes: What They Are and How They Work” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019).

2. Not all gains and losses on property are treated as capital gains and losses for purposes of determining tax liability. This complexity is set aside for purposes of this issue brief.

3. The maximum rate of 40.8 percent is the top statutory rate of 37 percent plus the 3.8 percent net investment income tax. Throughout this brief, the 3.8 percent additional Medicare tax or net investment income tax is included in the top rate whenever relevant.

4. This type of strategy is particularly effective when combined with corporate tax preferences, such as accelerated depreciation, that can offset any increase in corporate tax that might otherwise result from paying reduced wages.

5. The discussion in the text takes as given the existence of a separate corporate tax. However, a mark-to-market proposal could be further combined with a proposal for corporate integration. Similarly, it could be combined with a proposal that strives to index the tax code for inflation, though any such attempt would ideally do so comprehensively across the tax code—including debt instruments, for example—and not just in computing capital gains.

6. See, for example, David Kamin, “Taxing capital: paths to a fairer and broader U.S. tax system” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2016); David Miller, “A Comprehensive Mark-to-Market Tax for the 0.1% Wealthiest and Highest-Earning Taxpayers.” SSRN Paper (2016), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2710738.

7. See, for example, Ari Glogower, “Taxing Capital Appreciation,” Tax Law Review 70 (1) (2016): 111–176; Harry Grubert and Rosanne Altshuler, “Shifting the Burden of Taxation from the Corporate to the Personal Level and Getting the Corporate Tax Rate Down to 15 Percent,” National Tax Journal 69 (3) (2016): 643–676; James Kwak, “Reducing Inequality with a Retrospective Tax on Capital,” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy 25 (1) (2015): 191–244; Alan J. Auerbach, “Retrospective Capital Gains Taxation,” American Economic Review 81 (1) (1991): 167–178.

8. See Eric Toder and Alan Viard, “A Proposal to Reform the Taxation of Corporate Income” (Washington: Tax Policy Center, 2016); Grubert and Altshuler, “Shifting the Burden of Taxation from the Corporate to the Personal Level and Getting the Corporate Tax Rate Down to 15 Percent”; Lily Batchelder and David Kamin, “Taxing the Rich: Issues and Options” (Washington: Aspen Institute, forthcoming).

9. Jane G. Gravelle, “Capital Gains Tax Options: Behavioral Responses and Revenues” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2019).

10. The U.S. Treasury, the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation, and the Congressional Budget Office assign the full incidence of taxes on capital gains to savers. See Office of Tax Analysis, “Treasury’s Distribution Methodology and Results” (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2015), available at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/tax-analysis/Documents/Summary-of-Treasurys-Distribution-Analysis.pdf; Joint Committee on Taxation, “Overview of the Federal Tax System as in Effect for 2019” (2019), available at https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5172; Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2014” (2018), available at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53597.

11. “Distributional Financial Accounts: Levels of Wealth by Wealth Percentile Groups,” available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/efa/efa-distributional-financial-accounts.htm (last accessed August 12, 2019).