Unemployment Insurance is designed to help workers who are displaced, through no fault of their own, until they can find new jobs. It is natural to extend these benefits when the labor market is weak and job searches take longer to result in a new job. But benefits should not be so generous that the recipients delay taking new jobs.

Balancing these two policy prescriptions is difficult politically. Yet new analyses of recent data covering unemployed workers during the Great Recession and its aftermath indicate that the impact of unprecedented extensions of Unemployment Insurance on job uptake were smaller than previously thought while the benefits were extremely important to maintaining family incomes. The program helped sustain families and communities during an unusually long period of weak labor demand, helping to promote long-term labor market resiliency and higher future prosperity by helping the long-term unemployed remain out of poverty and attached to the labor market.

Extended Unemployment Insurance benefits expired at the end of 2013, and Congress is now considering whether and how to reinstate them. The new data and analysis detailed in this issue brief—based on the roll-out of extended benefits in 2008-2010 and the roll-back that began in late 2011—indicate that old views of the design of Unemployment Insurance need some updating. Specifically, the downsides of UI extensions are smaller than in past economic downturns, and there are some previously unanticipated upsides. Congress should take these findings seriously as it considers a possible reauthorization of the Emergency Unemployment Compensation program this year.

Read a PDF of the full document

Current labor market conditions

Unemployment insurance extensions are only authorized in weak labor markets, and understanding their effects requires understanding the context in which they operate. Although the Great Recession officially ended in 2009, a full five years later the labor market is still quite weak. The unemployment rate has fallen, from a peak of 10.0 percent in October 2009 to 6.7 percent in March 2014. But the share of the adult population that is employed is only 58.9 percent, down a full 4.0 percentage points from before the Great Recession and lower than at any point between 1984—when female labor force participation was much lower than today—and 2009. And the long-term unemployment rate, the share of the labor force that has been out of work for six months or longer, remains extremely high.

This crisis has been devastating for working people. More than 30 million “person-years” of employment were lost.[1] This represents potential earnings that vanished without a trace, cutting deeply into family budgets. And the overhang from the extended period of extreme labor market weakness will extend the pain much further, in at least three distinct ways. First, the weak labor market held down wages even for those workers who kept their jobs—the median full-time worker has not had a real wage increase in a decade. Second, workers who lost their jobs will probably see long-run declines in their earnings, as high as 20 percent per year for as long as 20 years.[2] Third, the cohorts of young people who have entered the labor market since the crisis began have had trouble getting their feet on the bottom rungs of the career ladder. This, too, will have long-lasting effects, depressing wages for much of their lives.[3]

The most important component of the policy response to a shock of this magnitude must be to ensure that the economy recovers quickly so that the damage does not continue. On this score, policymakers in Washington have done exceptionally poorly.

A second important component is to cushion people from the ill effects of the crisis while it lasts. Unemployment Insurance is a very important part of this cushion. Ideally, it should help fill in the hole in household budgets that is created when a worker is laid off, allowing the family to maintain its consumption during the job search.

The design of unemployment insurance policy trades off two objectives: We want to insure workers against job losses, but we don’t want to create incentives for workers who have lost their jobs to delay finding new work. The former pushes us toward more generous benefits—higher replacement rates and longer durations—while the latter consideration pushes in the opposite direction.

There has always been good reason to think that the insurance function of Unemployment Insurance is more important in weak labor markets. When there are few jobs to be had, it takes displaced workers a long time to find new jobs and job seekers thus need more support. At the same time, incentive problems are less severe in weak labor markets—jobless workers will be loathe to turn down an available job in the hope of something better, and even if these incentives do dissuade a worker from taking a job, there will be a long line of other workers ready to fill the open position, with little net impact.

This argument provides a rationale for a policy of making Unemployment Insurance more generous in downturns. And indeed this is what we saw early in the Great Recession: Where traditional UI benefits have averaged about $300 per week for no more than 26 weeks during the early years of the crisis, Congress both raised benefit levels, by $25 per week as part of the 2009 Recovery Act, and dramatically extended their duration, to as many as 99 weeks through much of 2010 and 2011.

Although this expansion was entirely consistent with the best understanding of optimal policy, it was quite controversial. Opponents argued that it would dissuade displaced workers from taking new jobs, and some have even attributed nearly the entire rise in unemployment during 2007-2009 to the disincentive effects created by extended Unemployment Insurance. [4] But these arguments are not well founded in the evidence. New data indicate that the recent extensions reduced job-finding rates [or job search efforts] only minimally.

Examining the most recent data

The roll-out of extended Unemployment Insurance benefits in 2008-2010 and the roll-back that began in late 2011—UI durations are now only about a quarter of their 2009-10 maximum—created a natural experiment allowing researchers to study the effects of extended UI benefits in weak labor markets. These studies indicate that old views of the design of Unemployment Insurance need some updating. Specifically, the downsides of UI extensions are smaller than in the past, and there are some previously unanticipated upsides.

The evidence indicates that extended Unemployment Insurance does reduce the likelihood that an unemployed worker will find a job in any given month, but by much less than we previously thought. Moreover, extended UI benefits have an important countervailing effect: Many unemployed workers who would have given up their job searches and exited the labor force are persuaded to remain in the job market because benefits are available only to those actively searching for work. This effect is at least as large as the effect on job finding.[5]

The effect of Unemployment Insurance extensions on labor force participation may turn out to be very important in the long run. An important concern as the weak labor market drags on is that workers who have been out of work for years or more may become detached from the labor market and unable to return to work. Any such effect would cast a long shadow over our future prosperity.[6] Although evidence is limited, the data appear to indicate that UI extensions help to reduce worker disconnection from the labor market, [7] and thus play an important role in returning our economy to eventual health.

Despite the accumulation of evidence that UI benefits are doing little to dissuade displaced workers from finding jobs, and may even be having a positive net effect on the labor market, the UI extensions put in place in 2008-2010 have been allowed to expire. Benefit durations have fallen to only 26 weeks in most states, just over a quarter of their peak level, and in some states they are much lower. North Carolina, for example, has cut durations to as short as 12 weeks, and has reduced benefit levels as well. As a consequence of these cuts, hundreds of thousands of workers have been thrown off Unemployment Insurance who might otherwise have received it.

Not surprisingly, this has done nothing to improve the labor market, which is limping along just as slowly now as it was in 2012 and 2013, before the UI extensions expired. There remains no sign that employers are having trouble filling most jobs, as would be expected if UI benefits were discouraging recipients from taking work. The evidence still points overwhelmingly to labor demand shortfalls as the primary problem.

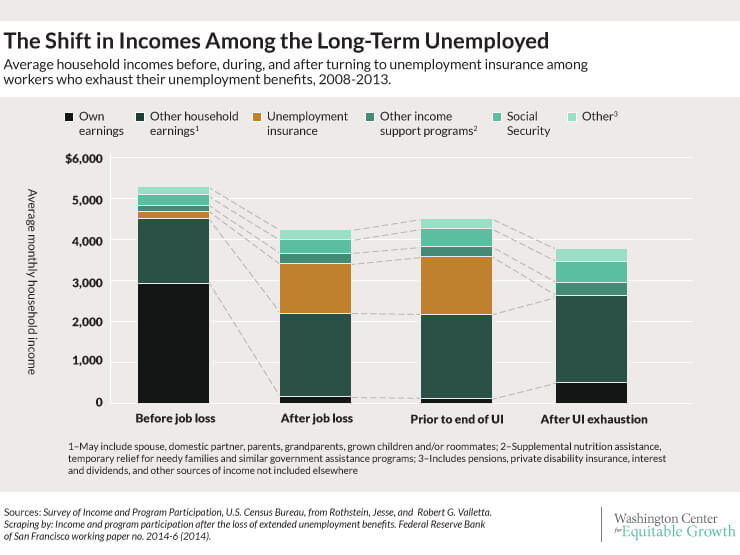

The cutback in UI benefits has, however, imposed great hardships on families and their communities. In recent work with Rob Valletta of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, I examined the trajectory of family incomes from initial employment, through job losses to spells of UI receipt, and then through UI exhaustion at the end of the spell.[8] We found what one would expect: Earnings fall dramatically when a worker loses his or her job, and UI benefits make up only about half of that loss on average.

When these benefits expire, family income takes another dramatic fall. Some families turn to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly called food stamps) or other government assistance programs, while others turn to early retirement and Social Security payments for support. But most families are able to do neither, and thus must live with sharply reduced incomes. The average recent UI exhaustee’s family has only 70 percent of its pre-displacement income. Many families, particularly those that previously had a single earner, have much less than this. These families are likely to have exhausted their savings long before, and thus face real hardship. Well over one-third of exhaustee families fall below the poverty line.

This is devastating to families. It also hurts their communities: Families without income to spend cannot support local merchants or service providers or make rent or mortgage payments, so the expiration of UI sends ripples throughout the local economy. Needless to say, few local economies can afford this right now, and the drag created by the expiration and exhaustion of Unemployment Insurance threatens to bring an already slow recovery to a dead stop.

Extended UI benefits cannot be the whole of our policy response to the ongoing weakness of the labor market. Many workers displaced in the downturn have outlasted even the maximum benefit extensions, and will need other forms of support to allow them to survive. And UI extensions alone will not provide enough of a fiscal boost to support a robust recovery. But the fact that this one tool will not finish the job cannot justify not starting. And the evidence that has accumulated during the Great Recession and the subsequent tepid recovery demonstrates that Unemployment Insurance is a useful and important tool, and that the recovery would have been even weaker and slower without it.

Jesse Rothstein is associate professor of public policy and economics at the University of California, Berkeley. He joined the Berkeley faculty in 2009. He spent the 2009-10 academic year in public service, first as Senior Economist at the U.S. Council of Economic Advisers and then as Chief Economist at the U.S. Department of Labor. Earlier, he was assistant professor of economics and public affairs at Princeton University. He received his Ph.D. in economics from UC Berkeley in 2003.

Endnotes

[1] A person-year represents one person employed for one year. I calculate this as the increase in the number of person-years of unemployment from what would have obtained had the unemployment rate remained at its November 2007 level of 4.7%. This assumes that the weakness of the labor market was not responsible for the sharp decline in the labor force participation rate, so is a substantial underestimate.

[2] See Jacobson, Louis S., Robert J. LaLonde, and Daniel G. Sullivan. “Earnings losses of displaced workers.” The American Economic Review (1993): 685-709; von Wachter, Till M., Jae Song, and Joyce Manchester. “Long-Term Earnings Losses due to Job Separation During the 1982 Recession: An Analysis Using Longitudinal Administrative Data from 1974 to 2004.” Working paper (2009).

[3] See Oreopoulos, Philip, Till von Wachter, and Andrew Heisz. “The short-and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4.1 (2012): 1-29; Oyer, Paul. “The making of an investment banker: Stock market shocks, career choice, and lifetime income.” The Journal of Finance 63.6 (2008): 2601-2628; Kahn, Lisa B. “The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy.” Labour Economics 17.2 (2010): 303-316.

[4] Barro, Robert. “The Folly of Subsidizing Unemployment,” Wall Street Journal, August 30, 2010. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748703959704575454431457720188. See also, Hagedorn, Marcus, Fatih Karahan, Iourii Manovskii, and Kurt Mitman, “Unemployment Benefits and Unemployment in the Great Recession: The Role of Macro Effects.” National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 19499, 2013.

[5] Rothstein, Jesse. “Unemployment insurance and job search in the Great Recession.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Fall (2011): 143-213; and Farber, Henry S., and Robert G. Valletta. Do extended unemployment benefits lengthen unemployment spells? Evidence from recent cycles in the US labor market. Working paper no. W19048, National Bureau of Economic Research (2013).

[6] See DeLong, J. Bradford, and Lawrence H. Summers. “Fiscal Policy in a Depressed Economy.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (2012): 233-297.

[7] Rothstein (2011); Farber and Valletta (2013).

[8] Rothstein, Jesse, and Robert G. Valletta. Scraping by: Income and program participation after the loss of extended unemployment benefits. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco working paper no. 2014-6 (2014).