Overview

Digital communications platforms, whether offered by a cable company, a telecommunications firm, or an Internet services provider, deliver the most important text and video content that powers our economy, educates our citizenry, and fuels our democracy. Yet the business dynamics of these platforms and the natural incentives of platform owners to overcharge consumers for their goods and services create enormous opportunities for competitive abuse—harming consumers and exacerbating economic inequality—unless vigorous public oversight corrects significant and pervasive market imperfections. These increasingly anti-competitive digital business practices also are a drag on our nation’s economic growth, causing consumers to overspend on these services far beyond what is necessary to induce any increased productive investments by firms in this key industry.

Download FileA communications oligopoly on steroids

Read the full PDF in your browser

Under U.S. law, antitrust enforcement is one critical element necessary to protect consumers and the competitive process. Yet antitrust by itself is not enough to ensure the marketplace benefits and potential progressive societal advancements that digital communications platforms offer. Antitrust enforcement can prevent the creation of monopolies and actions that diminish competition, but these laws are not designed to maximize competitive options or promote social policies such as expanded employment, equitable access to content, and overall freedom of expression. Only with appropriately focused regulatory oversight alongside strict antitrust enforcement can the service providers in the cable, telecommunications, wireless, and broadband industries be driven to offer competitive, nondiscriminatory, innovative, and socially beneficial video and broadband services that maximize consumer value and choice in both the economic market and the marketplace of ideas. These steps, in turn, will boost demand for these goods and services in the broader economy and spark more investments in innovation and new infrastructure.

This paper details the state of these communications industries in the first dozen years after enactment of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which opened the door to lax antitrust enforcement and excessive deregulation and led to highly concentrated oligopolistic markets that result today in massive overcharges for consumer and business services. 1 Prices for cable, broadband, wired telecommunications, and wireless services have been inflated, on average, by about 25 percent above what competitive markets should deliver, costing the typical U.S. household more than $45 per month, or $540 per year, for these services.2 This stranglehold over these essential means of communication by a tight oligopoly on steroids—comprised of AT&T Inc., Verizon Communications Inc., Comcast Corp., and Charter Communications Inc. and built through mergers and acquisitions, not competition—costs consumers in aggregate almost $60 billion per year, or about 25 percent of the total average consumer’s monthly bill.

The paper then examines the efforts by the Obama administration to arrest this uncompetitive trend by launching numerous regulatory interventions and enhanced antitrust enforcement.3 These efforts resulted in a change in course that was strongly positive for U.S. consumers and the economy. Alas, these actions could not address all of the structural harms caused by previous policy mistakes. What’s more, these ongoing antitrust problems in the communications sector are unlikely to be addressed by the new Trump administration, which has signaled that it will seek to reverse many of the gains to consumers achieved under the Obama administration.

Potential remedies, however, remain within reach of policymakers in Congress, at the Federal Communications Commission—the chief telecommunications regulatory agency in this business arena—and at the other two key federal antitrust enforcers, the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice. In the pages that follow, this paper will explain these complex antitrust and regulatory processes in the telecommunications sector, trace how antitrust and regulatory actions have performed since the enactment of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, and then showcase a number of efforts made by the Obama administration to protect consumers and strengthen competition in the various communications industries—efforts that were partially successful but are now under threat under the new Trump administration.

The need for dual antitrust and regulatory action in law and economics

Recent calls to revive antitrust enforcement in the U.S. economy, and particularly in the digital communications industries, in light of evidence of increasingly concentrated markets and broader dangers to society are long overdue. But sometimes these concerns are portrayed in too simplistic a manner. While some idealized version of antitrust actions may be theoretically capable of handling all competitive issues as well as the consequences of increased economic inequality and stunted economic growth in today’s economy, neither current antitrust jurisprudence nor contemporary economic analysis supports this simplistic vision. What’s also required—and what Congress has provided—are regulatory tools to promote both competition and other economic goals, in which case antitrust enforcement can work in tandem with targeted regulation to achieve many of the goals needed to create a more equitable and competitive marketplace in communications products and services.4

Most antitrust analysis is backward-looking, involving observed market outcomes that are considered to be the result of insufficient competition leading to conduct that is harmful to consumers. Structure is examined as the context that makes the conclusions about conduct more plausible. The lack of competition due to high levels of concentration, for example, makes it more likely that dominant sellers will be able to set prices above costs to earn excess profits, but antitrust tools generally are triggered only when abuses can be demonstrated.

Antitrust reviews of corporate mergers reverse this analytical flow because it is the one area where antitrust is forward-looking. That’s because structural analysis is central to the complaint that a merger will so greatly increase market concentration as to pose a threat to competition and raise the potential for the abuse of market power.

In both classic antitrust cases and merger reviews, however, the antitrust authorities prefer structural remedies such as divestiture of assets to shrink market power, rather than remedies that require them to regulate the conduct of companies in the marketplace. This means that market structure, conduct, and performance are focal points, yet basic market conditions receive less attention. In fact, antitrust enforcers do not generally address basic market conditions because they are beyond their policy reach.

Some characteristics of an industry make it unlikely that private investment and market forces will produce socially optimal outcomes.5 In some cases, investors cannot project or capture the benefits of the production of a good—public goods such as emergency call “enhanced 911,” or E-911, numbers or infrastructure, such as roads or communications networks that make an area much more functional. In other cases, consumers cannot project the benefits of more output, such as a so-called network effect, which makes the network more valuable to consumers, who can reach more people, and to producers, who can identify niches to expand output. As a result, supply or demand may be too little.

In other cases, economic characteristics lead to very large firms that boast strong economies of scale or scope, such as adding consumers or services, which spread costs across a larger base and make building two networks redundant and costly. The number of firms that the market can support may be very small—the minimum efficient scale is very large compared with the size of the market—resulting in weak competition and the threat of abuse of market power. These and other basic market conditions are mostly outside the purview of antitrust enforcers because they are not forward-looking in scope.

In these areas, regulation is necessary because it tends to be forward-looking.6 Legislation declares specific goals, often broadly defined, and grants a regulatory agency specific powers to pursue them. The Communications Act of 1934 gave the Federal Communications Commission, or FCC, substantial regulatory flexibility, and the courts have granted it deference as the expert agency. In merger reviews, for example, the FCC is charged with promoting competition—not just protecting it—and the public interest, which enables the agency to take a proactive role across a wide range of policies that address precisely the basic market conditions, structural factors, and performance goals that antitrust does not tackle effectively. This is very different from the purview of the two traditional antitrust enforcement agencies, the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice, which are directed solely to prevent the loss of competition.

As discussed below, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 was an effort to strike a new balance between the market and regulation that went awry because the act and those implementing it underestimated the continuing power of the fundamental, problematic characteristics of the industry. The benefits of injecting more competition could have been achieved without many of the negative consequences of the abuse of market power that was unleashed by lax regulation and antitrust enforcement.

The unique nature of digital communications and the role of antitrust enforcement and regulation

Infrastructure industries such as communications and now digital communications have long been recognized as unique from the point of view of U.S. economic and social policy. Although competition and markets have been the preferred form of industrial organization for economic activity, the extreme importance of infrastructure to a broad range of economic activity and the tendency for there to be very few providers of infrastructure services have led to additional oversight of these industries.7 Yet antitrust enforcement, even in its “golden age” of trustbusting in the first half of the 20th century, has never been seen as enough.8

In the communications sector, competition to connect wired and wireless services to homes and businesses cannot be counted on to prevent the abuse of market power because the number of firms in any market is small and barriers to entry are high.9 Because of its public goods value and powerful network effects, private facility owners cannot foresee or capture the value of diffuse benefits or externalities, so they will underinvest, harming consumers and economic competitiveness and growth. Seamless interconnection between communications networks and nondiscriminatory access to these networks may not develop or may not be sustained because the private interests of network owners are better served by blocking or charging very high prices for access and usage.

Communications has other characteristics that make it an even more unique concern in terms of fostering competition that boosts economic growth and lessens economic inequality. Whether it is the landline telephone of 100 years ago or the wireless and broadband of today, these are necessities with relatively low elasticities of demand and few or no substitutes. But basic market conditions mean that companies do not or will not deliver services to large and significant groups and areas because providing service is not profitable where costs are high or incomes are low. These characteristics lay the basis for conduct that abuses market power. In short, market imperfections and failures may weaken the effect of competition. As the leading text Economics of Regulation and Antitrust puts it:

If we existed in a world that functioned in accordance with the perfect competitive paradigm, there would be little need for antitrust policies and other regulatory efforts. All markets would consist of a large number of sellers of a product, and consumers would be fully informed of the product’s implications. Moreover, there would be no externalities present in this idealized economy, as all effects would be internalized by the buyers and seller of a particular product.

Unfortunately, economic reality seldom adheres very closely to the textbook model of perfect competition. Many industries are dominated by a small number of large firms. In some instances, principally the public utilities, there may even be a monopoly. Not all market failures stem from actions by firms. In some cases, individuals can also be contributing to the market failure.10

Here, it is important to note that the concern about the abuse of market power applies to both buyers and sellers—monopsony power is as big a concern as monopoly power. If one firm gains sufficient market power as a purchaser to depress the price it pays for inputs, such as content or equipment, then innovation and the supply of products can be diminished. In U.S. communications networks, Congress, regulators, and antitrust authorities have taken action to prevent the abuse of monopsony power given communications companies’ control over access to customers and the lack of competition. The concern about the ability of network owners to function as economic monopsonists is reinforced by their ability to control what they communicate and also is the cornerstone of democratic discourse.

The failure of the Telecommunications Act of 1996

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 was designed to give a strong push for competition but in a manner that was cognizant of the underlying difficulty of sustaining competition in the communications industries. Regulations were to be lifted only where competition had rendered them no longer necessary in the public interest. And a number of policies were instituted to try to promote and support competition, such as network sharing—or “unbundled telecommunications network elements” in industry parlance—and the removal of prohibitions on the entry of telephone and cable companies into each others’ markets.

These efforts to boost competition worked in some areas, but they left a great deal to be desired in others. The reason: After the 1996 act became law, policymakers unfortunately invoked the theory of competition where little real competition existed, and they prematurely removed regulatory protections in areas where they needed to remain in place. These decisions sparked a wave of mergers within and across segments of the industry, eliminating or frustrating “intramodal competition”—the head-to-head competition between firms using similar technologies—under the false hope that intermodal competition would be sufficient to protect consumers.11

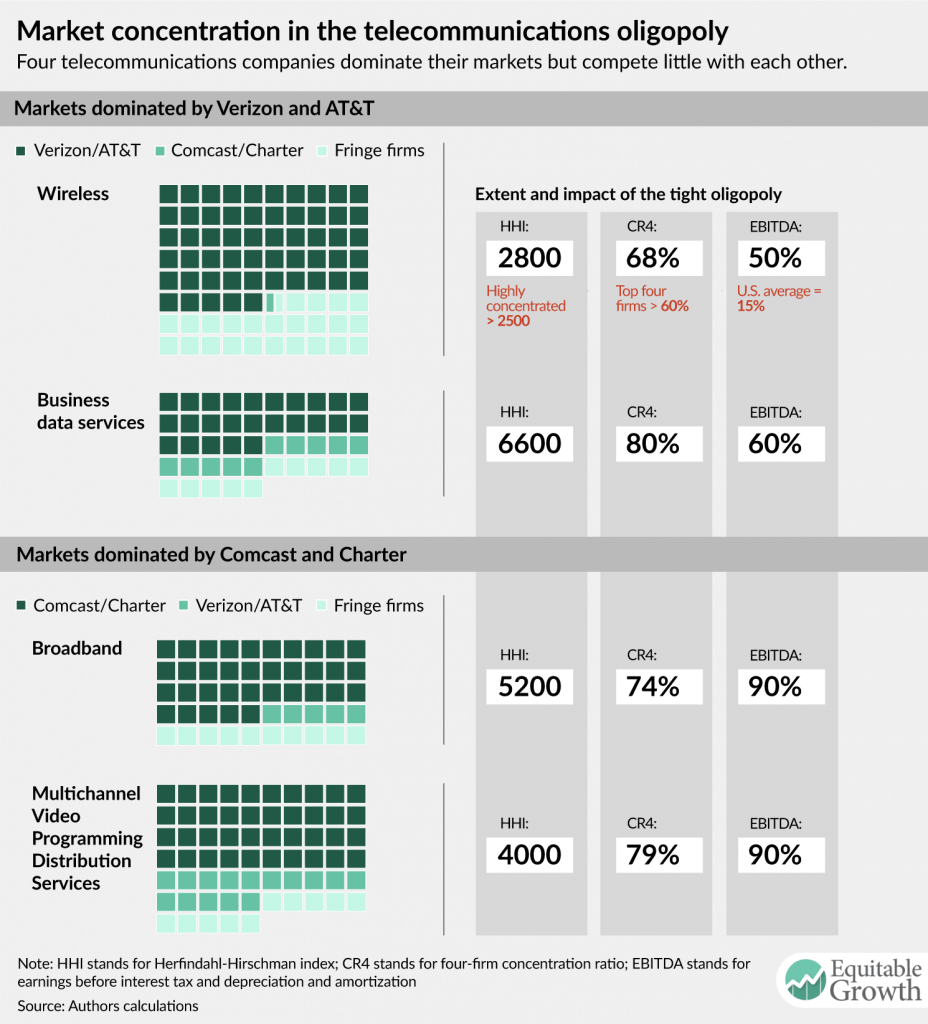

The eight regional telephone monopolies that emerged from the government’s breakup of the old AT&T national monopoly in the 1980s merged into two dominant wireline and wireless giants—Verizon and AT&T—that not only acquired the “Baby Bells” created by the breakup in 1984 of AT&T but also swallowed the large independent companies that had existed from the early days of the industry, such as the old General Telephone and Electronics Corporation, and the largest long-distance potential competitors. Similarly, local cable monopolies combined into regional powerhouses—Comcast and Charter—and developed cozy relationships with a similarly consolidating content industry. Lax antitrust enforcement combined with weak regulatory oversight resulted in the growth of what we call a “tight oligopoly on steroids.” By the standard definitions of antitrust and traditional economic analysis, a tight oligopoly has developed in the digital communications sector.12 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The figure above shows the national levels of concentration based on the so-called Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, or HHI, which antirust enforcers use to gauge concentration. The current threshold for finding a market highly concentrated is 2,500—until 2010 it was 1,800—so even at the national level, these markets are all highly concentrated.13 The markets are even more concentrated at the local level, which is where most market power is exercised, since consumers are dependent on local companies for access to communications services.

The figure above shows the local four firm concentration ratios based on the market shares of the dominant four firms in the market for each product. All are above the level—60 percent—at which markets are considered to be tight oligopolies.

The existence of such high levels of concentration indicates a strong possibility of the abuse of market power. The figure shows earnings before interest, taxes, and depreciation and amortization, or EBITDA, as a measure of profitability. This is the financial indicator frequently used by financial analysts.14 While EBITDA for segments of a business vary, the national average of just under 15 percent is considered healthy, so the EBITDA in these sectors are not merely supranormal, as defined in economic analysis, but they are astronomical.

The conditions for the exercise of market power do not stop with highly concentrated markets. The market division strategies that the dominant firms chose to pursue—and got away with after the 1996 Telecommunications Act—have resulted in a tight oligopoly on steroids for each of the services at the local level. They all started with local franchise monopolies, when the 1996 act was passed, and refused to enter new markets to compete head to head with their sister companies. Cable companies never overbuilt cable and never entered the wireless market. Telephone companies never overbuilt other telephone companies and were slow to enter the video market. Each chose to extend their geographic reach by buying out their sister companies rather than competing. This means that the potentially strongest competitors—those with expertise and assets that might be used to enter new markets—are few. This reinforces the market power strategy, since the best competitors have followed a noncompete strategy.

Regulatory policy was equally lax, deregulating services that were far from competitive based on the hope or hype that competition would grow in areas such as access to broadband services, specialized higher-speed connections for businesses—business data services—and mobile wireless.15 Inaction stalled progress on important economic goals to reduce inequality of access to affordable new Internet services as well as key social goals such as enhanced privacy, where the Federal Communications Commission took no action.

As a result, today these four firms enjoy geographic separation, technological specialization, and product segmentation that makes it easy to avoid competition. They cooperate—via TV Everywhere subscriber authentication—collaborate—via the Verizon-cable joint venture—or engage in reciprocal reinforcing conduct—via the purchase of out-of-region special access and political action—rather than compete. While some markets are slightly more competitive than others, the dominant firms are deeply entrenched and engage in anti-competitive and anti-consumer practices that defend and extend their market power, while allowing them to overcharge consumers and earn excess profits.

The consequences for consumers and the economy of this abuse of market power

As outlined in the Merger Guidelines—a set of federal rules governing antitrust enforcement—the antitrust authorities review mergers with an eye toward price increases, applying what’s referred to as the “small but significant, non-transitory price increase” standard.16 This standard, which defines small but significant as at least 5 percent and defines nontransitory as lasting at least two years, serves as a good baseline benchmark for evaluating pricing. By this standard, our analysis shows that the communications markets have performed poorly for the entire period since the passage of the 1996 Telecommunications Act.

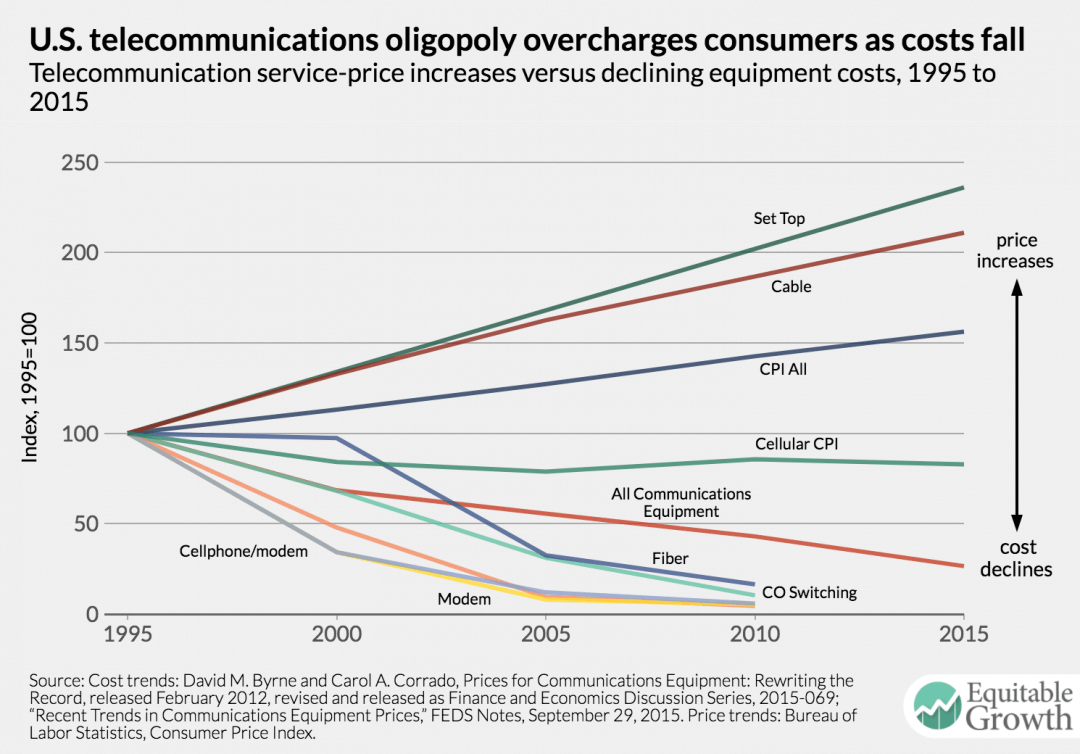

The pocketbook impact is rising prices for buyers and falling costs for sellers. In truly competitive markets, a significant part of cost reductions would be passed through to consumers. Based on a detailed analysis of profits—primarily EBITDA—we estimate that the resulting overcharges amount to more than $45 per month, or $540 per year, an aggregate of almost $60 billion, or about 25 percent of the total average consumer’s monthly bill.17 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

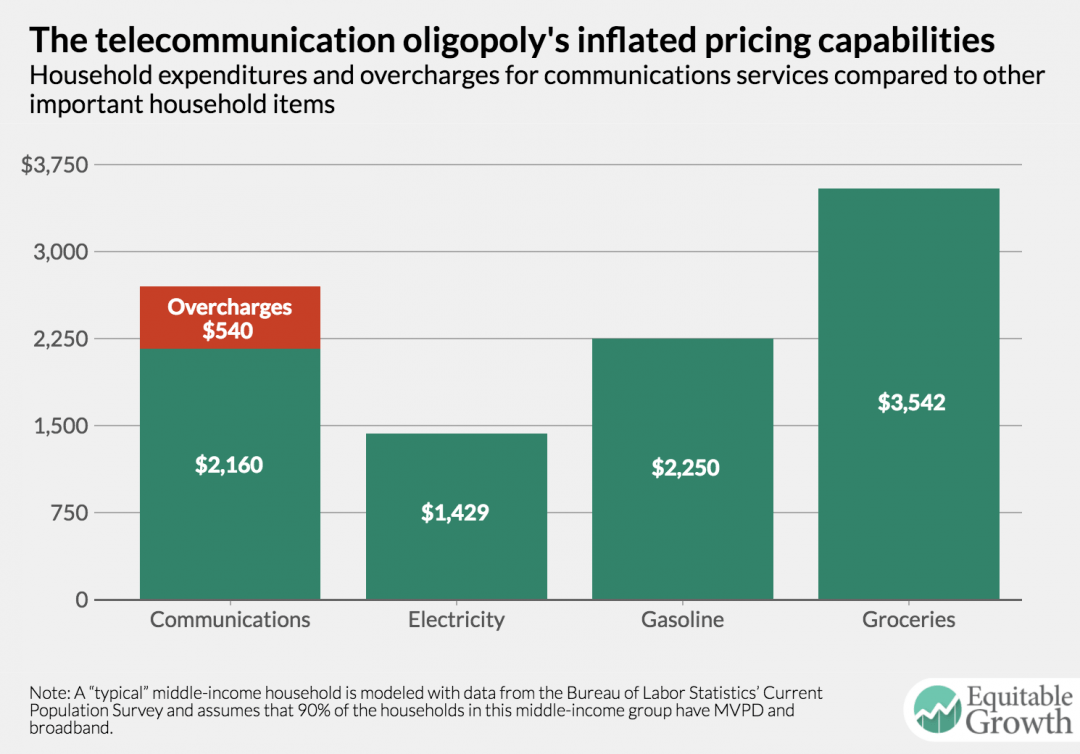

The impact of this abuse of market power on consumers is clear. According to the most recent Consumer Expenditure Survey18 by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the “typical” middle-income household spends about $2,700 per year on a landline telephone service, two cell phone subscriptions, a broadband connection, and a subscription to a multichannel video service.19 The new digital services, broadband and wireless, account for about two-thirds of the total. Adjusting for the “average” take rate of services in this middle-income group, consumers spend almost twice as much on these services as they spend on electricity.20 They spend more on these services than they spend on gasoline. Consumer expenditures on communications services equal about four-fifths of their total spending on groceries. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

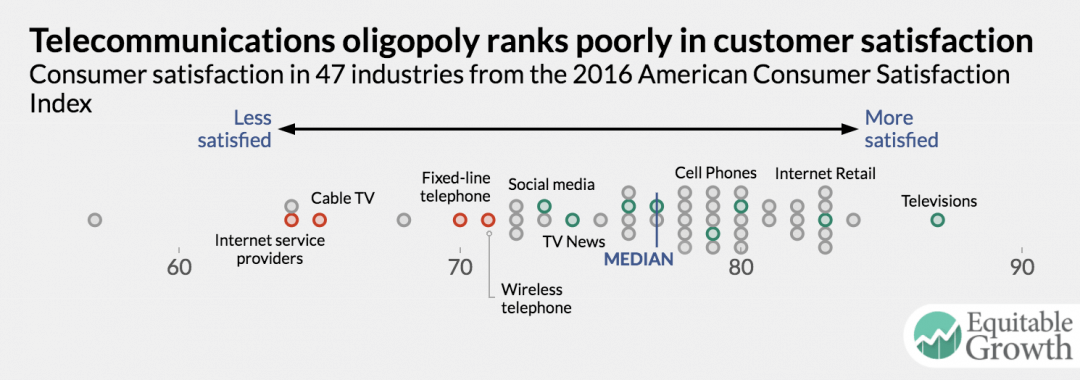

Given this massive overcharging, companies that have the market power to overcharge also lack the incentive to invest in customer service, we would expect consumers to be less than thrilled with these services. Indeed, the 2016 American Customer Satisfaction Index, which ranked 47 industries, shows that the services provided by the telephone company half of the tight oligopoly on steroids ranks 41st for wireless and 42nd for landline, while the half supplied by cable ranks 44th for video and 45th for Internet service. (See Figure 3.) Among 350 individual companies with rankings in 2015 or 2016, AT&T ranks 284th and 313th, depending on the service. Verizon is ranked equally poorly at 290th and 305th, while Charter Communications, ranked 333rd and 338th, and Comcast, ranked 340th and 340th, are even worse. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

The policy turnaround under the Obama administration

The Obama administration made a 180-degree reversal of direction in antitrust enforcement and regulation. Seven mergers in the telecommunications sector were considered and either rejected or approved subject to extensive conditions.21 Simultaneously, ambitious regulatory initiatives sought to redress past missteps and ensure that the benefits of platforms that both cooperate and compete (co-opetition) and positive externalities, flowing from a well-regulated communications infrastructure sector could be realized.

On the merger front, the Department of Justice and the Federal Communications Commission blocked two mergers—AT&T Inc. and T-Mobile US Inc. (the U.S. subsidiary of Deutsche Telekom AG), and Comcast Corp. and Time Warner Inc.—and jawboned another out of existence (Sprint Corp. and T-Mobile). The two antitrust enforcers also imposed extensive conditions on several approved mergers, among them Comcast and NBCUniversal Media LLC, AT&T and DIRECTV LLC, Charter Communication’s acquisition of Time Warner Cable and Bright House Networks LLC, and the cable joint venture Cellco Partnership Inc. between Verizon Communications and Comcast and Time Warner and Bright House. See the following sidebar for a closer look at the three different types of mergers—horizontal, vertical, and geographic extension—dealt with by the antitrust agencies during the Obama administration.

The FCC also shifted its attitude toward regulatory policy in the communications sector, seeking to promote competition and consumer welfare wherever possible.33 The agency sought to address the problems caused by excessive market power and concentration instead of wishing them away. The agency, for example, concluded that the deployment and adoption of broadband service was not adequate, as defined by the Communications Act, and issued rules to transform the universal service “affordability” program from one that supported only 20th century voice communications to one that supports 21st century broadband. And in two cases, the agency successfully turned to Title II of the Communications Act to remedy abusive market power. Specifically, the FCC:

- Declared broadband Internet access service to be regulated under Title II, making these services partially subject to common carrier obligations, even when they were provided by companies such as Comcast that had not been common carriers. This activated the language of the act that prevents dominant communications companies from imposing unjust, unreasonable, or discriminatory rates, terms, and conditions, although other common carrier obligations, like funding universal service were not activated.

- Concluded that under Title II, broadband consumer privacy required greater protection, and issued rules to prevent the customer proprietary information that broadband network service providers needed to operate the network efficiently from being used for other commercial purposes.

The importance of Title II in both of these situations is worth a short, deep dive.34

As communications have become more important in the economic, social, and political life of Americans, network owners have argued that the regulatory structure of the Communications Act has become outdated, in part because services that were once sold by separate firms using separate networks have converged onto broadband networks. Arguing that they are all just information services, which are, at best, very lightly regulated by the Communications Act, they would like to have regulation driven to the lowest common denominator, which is almost zero. Indeed, in many respects, they just want to do away with the Communications Act and rely solely on the antitrust laws.

Yet it became clear over the past decade that technological innovation and convergence are no guarantee against the abuse of market power. Under conditions of lax merger review and weak regulation, technological convergence leads to increased concentration and enhanced market power. The fundamental conditions of communications technology and the lack of competition that have long made it important to apply the dual oversight of antitrust and regulation are reinforced, not weakened. The stakes are huge in terms of the economic and social values that the United States has embraced for more than a century.

The following three cases show how the Obama administration decided that it would be more appropriate to continue the regulation of communications networks and converge regulation to the highest common denominator, Title II. The 1996 Telecommunications Act specifically preserved the definition of telecommunications—subject to the highest level of oversight—regardless of the technology used. Thus, Title II enforcement would continue to recognize the unique importance and market structures of the voice and video markets, even as those services are delivered over broadband.

Economic abuses

At issue before the Obama administration’s FCC was nondiscrimination in the provision of telecommunications services and efforts to misclassify services by the industry.35 And informing the actions of the agency were the widely recognized decisions in prior decades that promoted competition and ensured nondiscriminatory access to networks and seamless interconnection, which played a critical part in creating the conditions for the success of the Internet and wireless revolutions.36 These decisions were a mixture of regulatory and antitrust policy.

In the 1990s and 2000s, network owners offering Internet access service resisted the obligation to provide nondiscriminatory access.37 They initially sought classification of Internet access service as a cable service under Title VI of the Communications Act, which has no such obligation.38 They continued to resist being subject to a weak form of oversight—ancillary authority under Title I.39 Moreover, whenever network owners think that they might not be subject to strong rules on nondiscrimination, they have repeatedly engaged in aggressively discriminatory practices.

During the early days of this open access debate, Time Warner imposed a series of demands on independent Internet service providers that would have strangled competition. After it became obvious that network neutrality was at risk, the FCC in 2004 put forward a list of “Four Freedoms” that had little market impact due to a perceived lack of enforceability.40 For more than a decade, network owners repeatedly violated this approach to nondiscrimination, and the courts expressed concern about the use of FCC authority.41

The increasing importance of broadband Internet access service in the communications sector led the FCC in 2015 to classify this service as a Title II telecommunications service.42 Yet the agency restricted its own authority to a narrow subset of the Title II obligations and took a flexible approach to enforcement. This convinced the courts that this was the appropriate way to achieve the goals of the Communications Act.

Privacy and consumer abuse

Concerns about privacy have been a constant issue since mass market use of the Internet expanded in the mid-1990s.43 The Federal Trade Commission studied the problem repeatedly, and in 2008, the FTC and the U.S. Department of Commerce finally admitted that numerous, significant, and persistent market failures afflict privacy in the digital marketplace.44 Yet all three agencies failed to move aggressively to address the problems, with their powers limited under existing statutes.

Then, in 2017, the FCC—using the power under Title II to protect customer proprietary network information under the Communications Act—took action to prevent the abuse of consumer privacy by broadband network operators. The FCC concluded that the network operators have a uniquely powerful position from which to gather such information because they see everywhere the consumer goes—information that then can be sold to third parties. Using its new authority over broadband providers under Title II of the Communications Act, the agency made mandatory an existing voluntary FTC framework as the basis of its approach to protecting the privacy of broadband users.45

This effort of the FCC to protect consumer privacy was later overturned by the incoming 115th Congress earlier this year, using the Congressional Review Act procedures.46 The move by the new Congress exposed consumers to having their valuable personal information collected, monetized, and sold by the very Internet service providers that those same consumers must use to access essential services and content.

Premature deregulation of a vital service

The FCC at the end of the Obama administration also was considering rules to control network operators’ abuse of market power in the increasingly important and rapidly growing business data services market.47 High-speed, high-capacity communications services for businesses—called “special access” and later “business data services”—were long regulated as Title II common carrier services. Many of these connections were first built by the original telephone monopoly companies. They were among the first services deregulated after the passage of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, under the theory, or hope, that competition would develop to make close regulation of rates, terms, and conditions unnecessary.48

Business data services today are a pervasive input to the delivery of a wide range of goods and services, not just the communications services that consumers pay for directly. They are the high-speed, always-on connections that businesses have come to rely on for their routine communications, including mobile broadband and phone service; small, medium, and large businesses need much more capacity than a single telephone line, as do branch networks such as ATMs, gasoline stations, and the emerging Internet of things, all of which have many nodes that need to be online all the time.

The central role of business data services in the communications economy is matched by the high level of concentration for these services and the pattern of abusive conduct that developed when these services were prematurely deregulated starting in 1999.49 In fact, the FCC compiled the largest data set in its showing of the history of abuses in the business data services market. It shows that about three-quarters—at least 70 percent and as much as 80 percent—of consumers purchase business data services under the conditions of an absolute monopoly.50

Unfortunately, the FCC was unable to finalize reform of this market, and the intervening change of FCC leadership and the new Trump administration make robust action to remedy the effects of this uncompetitive market less likely. In fact, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s plan to roll back net neutrality protections51 is likely only to make matters worse, not better. Nevertheless, this issue demonstrates that targeted regulatory action can address competitive shortcomings, even if it is no guarantee that this regulatory action will occur. Indeed, the market abuses in the telecommunications sector that these changes in policy direction were intended to correct or prevent and the benefits of doing so are now at risk of being cut off by the Trump administration.

Conclusion

Antitrust enforcement and regulatory policy in the communications sector over the past 20 years demonstrate both the potential benefits of effectively aligned interventions and the enormous costs resulting from failed industry oversight. In such markets where historical monopolies, capital-intensive investments, and generally high levels of market concentration have only recently been challenged by policy adjustments and technological breakthroughs, there is very little margin for error if policymakers want to harness the full economic potential of the communications sector in ways that boost sustainable economic growth that is fair and equitable.

Early “hands off” antitrust and regulatory policy prevented new potential competitors from experimenting, solidified the dominance of telecommunications incumbents through regional expansion, and ossified the natural economic tendencies in these markets—thereby leading to massively inflated prices for consumers. More recently—and especially under the Obama administration—more aggressive intervention in proposed mergers and parallel regulatory actions designed to expand competitive opportunities for wireless, broadband, and broadband-delivered video services broke some of the price-inflating cycle, unleashed substantial innovation in the video streaming market, and started to police against new potential abuses of dominance in data and transmission bottlenecks.

The challenge in telecommunications and network industries that was recognized a century and a quarter ago remains relevant today. These industries benefit from immense economies of scale and scope that lead to large size and the threat of market power. We call them platforms today. They impact a wide range of economic and social activities that ride on these platforms and public policy should not destroy the economic benefits while it prevents the abuse of the inherent market power. The Progressive Era response was a nuanced mix of regulation and antitrust enforcement. The more dynamic the sectors of the communications industry, the more difficult and important is the need to find the right mix.

The key lesson in the communications sector is that vigorous regulation and antitrust enforcement can create the conditions for market success. But balance is the key. Technological innovation and convergence are no guarantee against the abuse of market power, but the effort to control the abuse of market power should not stifle innovation. If the Trump administration jettisons the enforcement practices of the past eight years, then the telecommunications sector is likely to see a wave of new consolidation and a dampening of the price cutting and innovative wireless and broadband services that have been slowly emerging. These markets will not remonopolize, but they will become a tighter oligopoly on stronger steroids even more dominated by two or three vertically integrated giants charging vastly inflated prices and asserting excessive power over the marketplace of ideas.

End Notes

1. This paper draws heavily on Gene Kimmelman and Mark Cooper, “Antitrust and Economic Regulation: Essential and Complementary Tools to Maximize Consumer Welfare and Freedom of Expression in the Digital Age,” Harvard Law & Policy Review 9-2 (2015): 403, available at http://harvardlpr.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/9.2_5_KimmelmanCooper.pdf; Mark Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved: How a Tight Oligopoly on Steroids Undermines Competition and Harms Consumers in Digital Communications Markets.” Working Paper (Roosevelt Institute, 2016), available at http://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Overcharged-and-Underserved.pdf.

2. See Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapter IX.

3. Ibid., Chapter I.

4. Market structure affects conduct, which in turn determines market performance, but basic conditions set the context in which structure and conduct operate. See Frederic M. Scherer and David Ross, Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance, 3rd edition (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), p. 5.

5. John B. Taylor (John B. Taylor, Economics (HoughtonMifflin, 1998, Glossary) provides a series of simple definitions for these concepts in the glossary: Public good—a good or service that has two characteristics: non rivalry in consumption and nonexcludability; Public infrastructure investment/project—purchases of capital by goods for use in as public goods, which add to the productive capacity of society/an investment project such as a bridge or jail funded by government designed to improve publicly provided services such as transportation or criminal justice; Externality—the situation in which the cost of producing or the benefit of consuming a good spills over onto those who are neither producing nor consuming the good; Economies of scale—also called increasing returns to scale, a situation in which long-run average total cost declines as the output of the firm increases; External economies/diseconomies of scale—a situation in which growth in an industry causes average total cost for the individual firm to fall/rise because of some factor external to the firm; Minimum efficient scale—the smallest scale of production for which long-run aver-age total cost is at a minimum.

6. See Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapter V.

7. Alfred Kahn, The Economics of Regulation: Principles and Institutions, Volume I (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1988), p. 11. The importance of these industries is measured not merely by their own sizable share in total national output but also by their very great influence as suppliers of essential inputs to other industries on the size and growth of the entire economy. These industries constitute a large part of the “infrastructure” uniquely prerequisite to economic development. On the one hand, they condition the possibilities of growth—as Adam Smith recognized, the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market, and the latter depends on the availability and price of transportation. On the other hand, because many of these industries are characterized by great economies of scale, their own costs and prices depend in turn on the rate at which the economy and its demand for their services grow.

8. The Interstate Commerce Act, the granddaddy of federal regulation, was passed in 1887, primarily to regulate railroads, but in 1910 it was extended to the telephone industry. The Sherman Antitrust Act, the foundation of U.S. antitrust policy, was enacted in 1890 and extended by the Clayton Antitrust Act in 1914; it was extended to all corporations in the Federal Trade Commission Act. One of the first consent decrees signed by the Department of Justice dealt with AT&T. Antitrust and regula-tion have been intertwined ever since. See Kimmelman and Cooper, “Antitrust and Economic Regulation.”

9. The level of competition that is possible in a particular market depends on characteristics such as population density and geography, as well as characteristics with a regulatory component such as ease of permitting, availability of public rights of way, access to conduit and utility poles, and so forth. In many cases, communications infrastructure markets tend toward natural monopoly or require public subsidy, municipal or cooperative ownership, or some other structure to be possible at all.

10. W. Kip Viscusi, John M. Vernon, and Joseph E. Harrington, Economics of Regulation and Antitrust, 3rd edition (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), pp. 2–3.

11. See appendix.

12.

For sector-specific analyses, see Cooper, “Overcharged

and Underserved,” Chapters XI, XII, and XIII.

13. According to the Horizontal Merger Guidelines, moderately concentrated markets have a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index between 1,500 and 2,500, and highly concentrated markets have an HHI above 2,500. See U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, Horizontal Merger Guidelines 19 (2010).

14. Investopedia described earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization as follows: While average EV/EBITDA values vary by sector and industry, a general guideline is an EV/EBITDA value below 10 is commonly interpreted as healthy and above average by analysts and investors. As of 2015, the average EV/EBITDA value for the overall market is 14.7.

The EV/EBITDA Multiple—The name of this metric indicates the formula used in its calculation. The value of the metric is determined by dividing a company’s enterprise value (EV) by its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). The numerator of the formula, the EV, is calculated as the company’s total market capitalization and preferred shares and debt, minus total cash.

This popular metric is widely used as a valuation tool, allowing investors to compare the value of a company, debt included, to the company’s cash earnings less noncash expenses. It is ideal for analysts and potential investors looking to compare companies within the same industry. Typically, EV/EBITDA values below

10 are seen as healthy, but comparison of relative values among firms operating in the same industry is a good way for investors to determine companies with the healthiest EV/EBITDA within a specific sector.

Benefits of EV/EBITDA Analysis—Though the price-to-earnings, or P/E, ratio is often primarily used as a valuation tool, there are benefits to using it along with the EV/EBITDA, or to using the latter on its own. The EV/EBITDA is considered by some to be a better valuation metric because it remains unaffected by changing capi-tal structures and offers fairer comparisons of companies with capital structures that differ. It also removes the effects of noncash expenses on a company’s value.

15. In telephony, the unbundled network element, or UNE, approach failed. In special access, new facilities-based competition did not emerge in many markets. In consumer broadband, weak regulation—no line-sharing requirements and weak or no net neutrality rules—was justified by the phantom of facilities-based competition, which proved to be either largely imaginary—as in broadband over power line—or transitory, as copper-line-based Digital Subscriber Line proved to be far inferior to coaxial cable and fiber. In mobile wireless, the presumption of competition allowed the major incumbents to increase their spectrum holdings unencumbered by an effective competition-promoting screen.

16. Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapters II and IV.

17. Ibid., p. 5.

18. The most recent survey available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics is for the year ending July 2015. The comparisons here use the middle quintile, which has a mean income before taxes of just under $49,000 per year.

19. The typical middle-income household—in the third quintile of the income distribution—buys these services, according to the recent Consumer Expenditure Survey, Mid-year, 2016.

20. Instead of looking at the “typical” middle-income household we analyzed above, the Consumer Expenditure Survey provides average expenditures for all households, whether or not they take services. The expenditures per household estimated in this way look smaller because a significant number of households that have no expenditures are included in the denominator used to calculate the average.

21. Kimmelman and Cooper, “Antitrust and Economic Regulation”; Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapters VI and VII.

22. Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapters VI and XII.

23. Ibid., pp. 65–66.

24. See Bureau Staff Analysis and Findings in Applications of AT&T, Inc. and Deutsche Telekom AG for Consent to Assign or Transfer Control of Licenses and Authorizations, WT Docket No. 11-65 (rel. Nov. 29, 2011).

25. Yankee Group, 2011. Yankee Group, 2011, ATT/T-Mobil Merger: More Market Concentration, Less Choice, Higher Prices.

26. See Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapters VII and XIII.

27. Comcast’s incentives and ability to raise the cost of or deny NBCUniversal programming to its distribution rivals, especially Online Video Distributors, will lessen competition in video programming distribution. (DOJ, 2011: 4, 52). In public, Comcast executives claimed that OVDs did not pose a competitive challenge; in private, they thought and acted in exactly the opposite manner. In fact, in the FCC order, which reviews the record in detail, there are almost 50 citations to proprietary documents that contradict the company’s public statements. This is approximately one-third of all the citations to proprietary documents in the body of the FCC order. In addition to the key issue of OVD competition, these citations covered other key issues, including exclusionary conduct with respect to multichannel video programming distributors, or MVPDs; online distribution of content affecting both OVDs and MVPDs; and broadband Internet access service.

28. See U.S. Department of Justice, Competitive Impact Statement, United States v. Comcast Corp., 1:11-cv-00106 (D.C.C. Jan. 18, 2011). Other relevant documents can be found at U.S. Department of Justice, “U.S. and Plaintiff States v. Comcast Corp., et al.,” available at https://www.justice.gov/atr/case/us-and-plaintiff-states-v-comcast-corp-et-al (last accessed June 30, 2017).

29. In the Matter of Applications of Comcast Corporation, General Electric Company and NBC Universal, Inc. For Consent to Assign Licenses and Transfer Control of Licensees Memorandum opinion and order, MB Docket No. 10-56 (rel. Jan. 20, 2011).

30. For a discussion, see Kimmelman and Cooper, “Antitrust and Economic Regulation.” Antitrust includes a string of actions: Old AT&T consent decree (19140, the Supreme Court decision in the Associated Press case, the AT&T breakup, and prime time monopolization. Legislation includes actions such as the cable compulsory license, must carry, and retransmission consent. FCC actions include the Carterfone, computer inquiries, and Financial Interest and Syndication rules.

31. Application and Public Interest Statement, In the Matter of Applications of Comcast Corp. and Time Warner Cable Inc. for Consent to Transfer Control of Licenses and Authorizations (Application), MB Docket No.14-57, before the Federal Communications Commission (rel. Apr. 8, 2014).

32. The Economist, “Turn it off: American regulators should block Comcast’s proposed deal with Time Warner Cable,” March 15, 2014, available at http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21598997-american-regulators-should-block-comcasts-proposed-deal-time-warner-cable-turn-it.

33.

See Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapters

XV and XVII.

34. Mark Cooper, “The Long History and Increasing Importance of Public Service Principles for 21st Century Public Digital Communications Networks,” Journal on Telecommunications and High Technology Law 12 (1) (2014): 1–54; ibid., Chapter XV.

35. See Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapters VIII and XVIII; Mark Cooper, “The ICT Revolution in Historical Perspective: Progressive capitalism as a response to free market fanaticism and Marxist com-plaints in the deployment phase of the digital mode of production,” Paper presented at Telecommunication Policy Research Conference, 2015; Federal Communications Commission, “The Digital Past as Prologue: How a Combination of Active Public Policy and Private Investment Produced the Crowning Achievement (to Date) of Progressive American Capitalism, Regulating the Evolving Broadband Ecosystem,” Paper presented at American Enterprise Institute/University of Nebraska Forum, September 10, 2014.

36. See, for example, Federal Communications Commission, “Connecting America: The National Broadband Plan” (2010), pp. 49 and 58, available at https://transition.fcc.gov/national-broadband-plan/national-broad-band-plan.pdf.

37. Dial-up Internet service providers (ISPs) were traditionally unregulated, but consumers accessed them over regulated, Title II telephone networks. Those regulations ensured that consumers could access the dial-up ISPs of their choice without discrimination from the network owner. When broadband integrated the ISP and network functions into one service—and as new technologies such as cable began to offer telecommunications service—broadband ISPs sought to bring the entire service down to the lowest level of regulation, leaving behind the obligation of network owners to provide nondiscriminatory access

38. See citations in Inquiry Concerning High-Speed Access to the Internet Over Cable & Other Facilities et al., Declaratory Ruling and NPRM, 17 FCC Rcd 4798, 60-69 (2002). AT&T and Cox were among the companies making this argument.

39. See Comcast v. FCC, 600 F.3d 642 (2010).

40. The Four Freedoms were described in a speech titled “Preserving Internet Freedom: Guiding Principles for the Industry” (Michael K. Powell, “The Digital Broadband Migration: Toward a Regulatory Regime for the Internet Age,” Remarks before Silicon Flatirons Symposium, University of Colorado School of Law, Boulder, Colorado, February 8, 2004. The FCC’s first attempt to enforce these freedoms against an ISP was overturned in Comcast Corp. v. FCC, 600 F.3d 642 (D.C.C. 2010).

41. See, for example, Comcast Corp. v. FCC, 600 F.3d 642 (2010).

42. Protecting and Promoting the Open Internet, Report and Order on Remand, Declaratory Ruling and Order, 30 FCC Rcd 5601 (2015).

43. See Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapter XVII.

44. Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Staff Report: Self-Regulatory Principles for Online Behavioral Advertising” (2009), available at https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-staff-report-self-regulatory-principles-online-behavior-al-advertising/p085400behavadreport.pdf.

45. Protecting the Privacy of Customers of Broadband and Other Telecommunications Services, WC Docket No. 16-106, 2016 WL 6538282 (2016).

46. Disapproving the rule submitted by the Federal Communications Commission relating to “Protecting the Privacy of Customers of Broadband and Other Telecommunications Services,” Public Law 22, 115th Cong., 1st sess. (April 3, 2017).

47. See Cooper, “Overcharged and Underserved,” Chapters X and XI.

48. See Access Charge Reform, CC Docket No. 96-262; Price Cap Performance Review for Local Exchange Carriers, CC Docket No. 94-1; Interexchange Carrier Purchases of Switched Access Services Offered by Competitive Local Exchange Carriers, CCB/CPD File No. 98-63; Petition of U.S. West Communications, Inc. for Forbearance from Regulation as a Dominant Carrier in the Phoenix, Arizona MSA, CC Docket No. 98-157, Fifth Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 14 FCC Rcd 14221 (1999).

49. The record shows that the business data services market exhibited strong structure (high concentration, no good substitutes, high economic barriers to entry, deep-pocketed incumbents), conduct (artificial contractual barriers to entry, cross subsidies, price squeezes and foreclosures of competitors, reciprocity in multimarket contracts) and performance (high prices, high profits, poor service) characteristics that strongly indicate the necessity of regulation. See Business Data Services in an Internet Protocol Environment, 31 FCC Rcd 4723, ¶¶. 160-237 (2016).

50. This is using a fairly lax geographic definition of the market. The remainder have, at best, a duopoly—one competitor serving someone in the building. In very few circumstances do customers have four or more competitors. The economic analysis shows that competition reduces prices and that the more vigorous the level of competition, the larger the price reduction. The impact of eight or more competitors, which is likely very rare, is a price reduction of 43 percent. Adding the eighth competitor lowers prices by about 10 percent, which exceeds the small but significant, nontransitory increase in price standard.

51. Ajit Pai, “The Future of Internet Freedom,” Remarks at Newseum, Washington, DC, April 26, 2017, available at http://transition.fcc.gov/Daily_Releases/Daily_Business/2017/db0426/DOC-344590A1.pdf.