Student debt illustration by David Evans, Equitable Growth

Student loans in the United States are now the second-largest source of debt, totaling $1.1 trillion shared among 42 million people with no sign of slowing down. Unfortunately, many questions about student debt, the characteristics of borrowers, and the nature of delinquency remain unanswered, primarily because agencies and researchers alike lacked access to the rich data in the U.S. Department of Education’s loan portfolio.

That changed last week when Adam Looney of the U.S. Department of the Treasury and Constantine Yannelis of Stanford University released an impressive new report that makes use of administrative data on student borrowing and earnings from linked, de-identified tax records to explore the student debt terrain.

Student debt nearly quadrupled over the past 15 years, and Looney and Yannelis find that the accelerated growth is largely due to a new type of borrower: students attending for-profit colleges. During the Great Recession, the number of students attending for-profit universities grew significantly in response to poor employment opportunities and a weak labor market. As a consequence, the number of borrowers grew too. Looney and Yannelis find that most of these “non-traditional” borrowers are vulnerable individuals who mostly come from lower-income backgrounds. Although average loan balances for borrowers who graduate from for-profit schools are smaller than those of nonprofit undergraduates or graduate students, these for-profit students face worse labor market opportunities, lower earnings, and, ultimately, much higher delinquency rates than their traditional college counterparts.

But just because the student loan crisis is concentrated among non-traditional borrowers does not mean that students attending a selective, non-profit, four-year university have it easy: The current labor market is not kind to young workers, even with traditional college degrees.

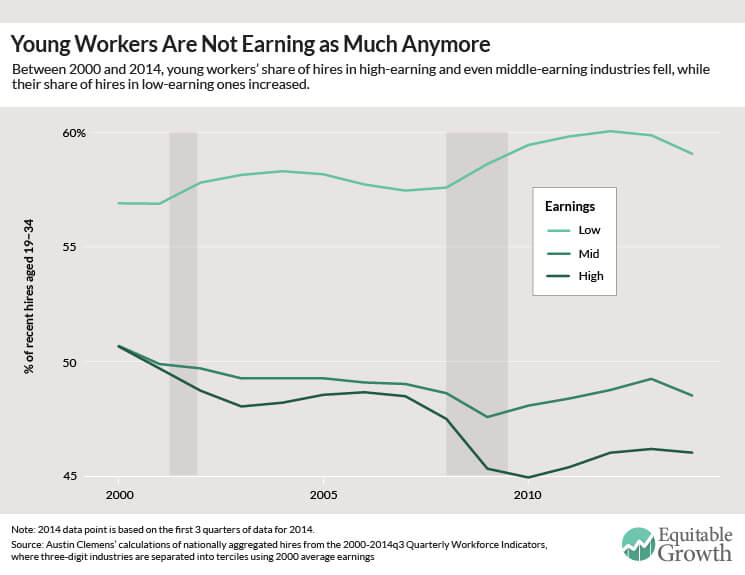

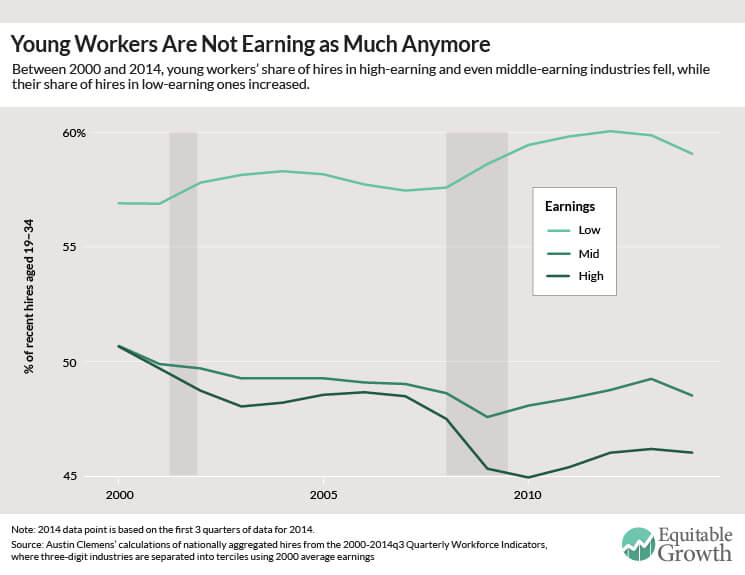

Young workers rely on job-to-job flows—transitioning between jobs to find better offers—in order to build their careers, move up the job ladder, and grow their earnings. Low unemployment allows workers to quit their jobs to search for more fruitful employment. When the labor market contracted during the Great Recession of 2007-2009, however, these job-to-job flows fell. Economists Giuseppe Moscarini of Yale University and Fabien Postel-Vinay of University College London find that during the recession, the jobs ladder shut down, trapping young workers in low-wage jobs. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The danger for recent college graduates is that carrying a large load of student debt requires young people to remain employed, even at jobs that don’t pay well, and hence restricts their ability to search out better opportunities for long-term earnings growth.

Joseph Altonji, Lisa Kahn, and Jamin Speer of Yale University report that all recessions have a damaging long-term effect on recent college graduates no matter what they majored in. For the average major, a recession means a 10 percent reduction in earnings in their first year out of college. In past recessions, high-paying majors such as engineering were less adversely affected, but in the Great Recession, even an engineering degree wasn’t sufficient protection. The three researchers find that between 2007 and 2009, the effect of unemployment on earnings halved the relative advantage that a high-paying major previously guaranteed.

So if young, traditional college graduates are being challenged by the post-recession labor market, what happens when high levels of student debt are thrown into the mix? In a recent paper, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California-Berkeley find that between 1986 and 2012, the wealth of the bottom 90 percent of the wealth distribution in the United States didn’t grow at all. With the little wealth that is, it’s unlikely that recent graduates with large student debt are able to accumulate any savings after servicing their student debts. In fact, the Pew Research Center’s tabulations of the Survey of Consumer Finances show that college-educated householders under 40 who have student debt have one-seventh of the wealth of people who don’t.

Student debt is a long-term burden in other ways too. Paying off college loans displaces other costs associated with our traditional perception of U.S. adulthood and the economic life-cycle. Economists David Cooper and J. Christina Wang of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston find that homeownership rates among college graduates ages 30 to 40 are lower for households with student debt. Similarly, other studies show that car ownership and marriage rates are also lower for young student borrowers.

As the student debt load grows for young borrowers, it is clear there may be long-term effects on young workers’ economic security. Just a generation ago, higher education was considerably more affordable or at least heavily subsidized by state governments, enabling young workers to begin saving and eventually realize the American Dream. But now, higher education is a transformative economic burden for the young workforce. And for the amount of student debt that graduates face upon entering the workforce, higher education certainly has not yielded commensurate benefits.