The Earned Income Tax Credit is a federal refundable tax credit designed to encourage work, offset federal payroll and income taxes, and raise living standards for low- and middle-income working families. Introduced in 1975, the EITC has grown to be one of the largest and least controversial elements of the U.S. welfare state, with 26.7 million recipients sharing $63 billion in total federal EITC expenditures in 2013.

The placement of the EITC within the tax code has three important effects:

- It provides a simple means of administering the credit without the large overhead of caseworkers and other staff needed for traditional means-tested spending.

- It symbolically links the credit to participation in the formal economy—non-workers are ineligible. This is also an important source of popularity among politicians and policymakers on both sides of the aisle, and also likely reduces the “stigma” that attaches to recipients of traditional welfare.

- Tax credits are not always perceived as spending, and may not count toward congressional spending caps.

The broad political support is buoyed by an expansive academic literature that details the EITC’s benefits. Research over the past two decades has documented large increases in net incomes for low-income families who work, and startling improvement in the well-being of children in those families. EITC expansions of the 1990s dramatically increased work among single parents as well (though the expansions may have had much smaller negative effects on the employment of secondary earners in married couples). Recent research has also found extremely important benefits for children’s educational achievement and attainment.

This brief will provide an overview of the academic research evaluating the EITC’s success in boosting well-being, reducing poverty, and encouraging work among working parents. It will also detail some unintended consequences of the EITC, and provide a brief outline of proposed modifications.

View full PDF here alongside all endnotes

Who is eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit, and for how much?

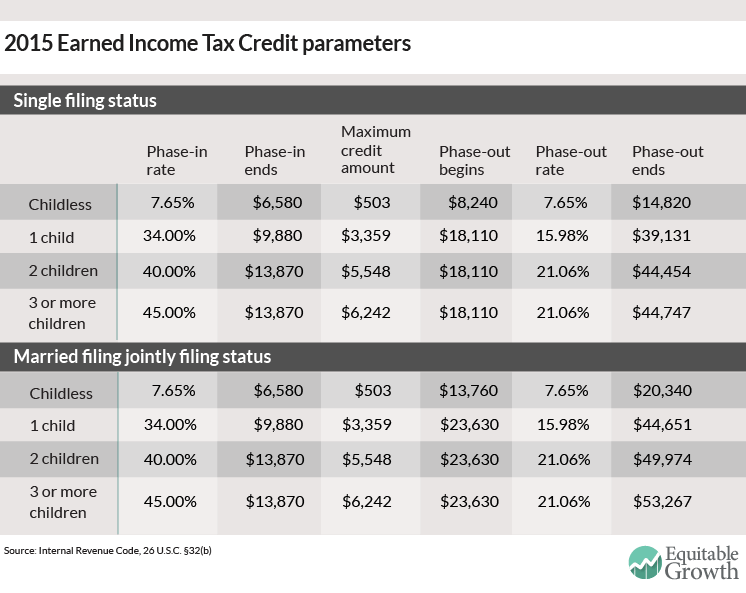

The EITC primarily goes to working parents with children, although a small number of childless individuals are also eligible. In the 2015 tax year, families with incomes below $29,000 to $53,300 (depending on the number of children and marital status) were eligible. For childless individuals, the threshold is $14,820 (or $20,300 for a married couple), and the credit is much smaller. (See Table 1 in Appendix.)

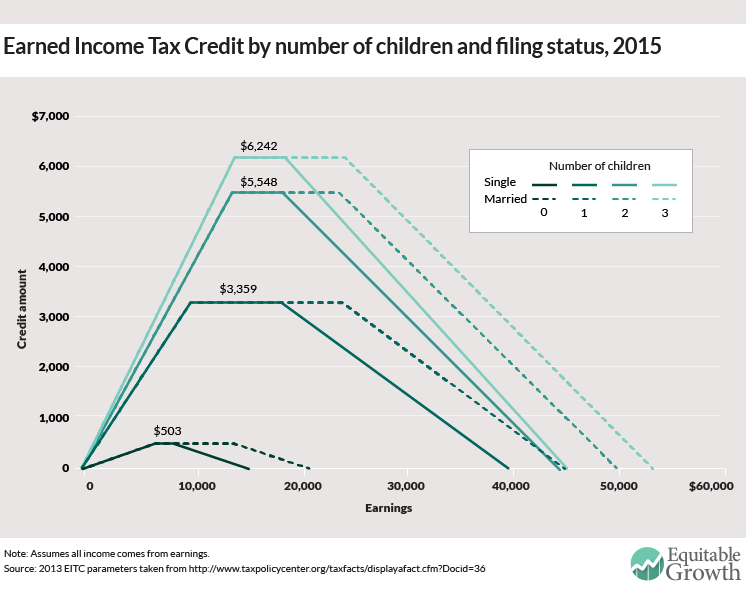

The size of the credit is dependent on how much a worker earns, the family structure (married or single), and the number of children. (See Figure 1.) For each family type, the credit is a fixed percentage of earnings until it reaches its maximum. Beyond this point, the credit is unchanged even as earnings continue to rise. For a married couple with two children, this “plateau” range spans earnings from $13,870 and $23,630, over which the credit is a constant $5,548. The credit then phases out until it reaches zero, at an earnings level of $49,974 for a married couple with two children.

In addition to the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, a number of states have incorporated EITCs into their own tax systems. These states typically offer a refundable (but sometimes non-refundable) credit equal to a percentage of the tax filer’s federal EITC. As of now, 26 states and the District of Columbia have their own EITC programs, ranging from 4 percent (for a family with one child in Wisconsin) to 40 percent (Washington, D.C.) of the federal credit. California is the most recent state to add a state EITC, with a program that takes effect in tax year 2015.

Does the Earned Income Tax Credit encourage work?

The EITC’s structure can be expected to encourage work among single parents, but to discourage it for many would-be secondary earners in married couples. Among workers, some face incentives to work more while many more face incentives to work less.

We begin with the case of a single parent faced with a decision whether to work at all. If she does not work, she will not receive an EITC (although she may receive Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, food stamps, or other transfers). If she does work and her earnings are less than $44,454 (for a two-child family), she will receive a positive EITC. This will partially offset other income taxes if any are owed, and will be refunded if they are not. Clearly, the EITC tilts this decision in favor of working, dramatically so for an individual with potential earnings below the end of the plateau range (which is $13,870 in 2015 for a single mother with two children).

For married couples, the effect can be the opposite. If one spouse makes enough to take the family out of the phase-in range on their own, then the second earner can only reduce the family’s credit by working. And while families in the phase-in range are encouraged to work more, those in the phase-out range may be encouraged to work less in order to be eligible for a larger EITC payment.

A large body of literature empirically examines the labor supply effects of the EITC expansion in the 1990s. Essentially all of the studies agree that this expansion led to sizeable increases in single mothers’ employment rates, concentrated among less-skilled women and among those with more than one qualifying child. There is some evidence of declines in married women’s labor supply, but this effect is unambiguously smaller.

What are the unintended consequences of the Earned Income Tax Credit?

Standard public economic theory implies that a negative effective tax rate that encourages more people to work will lead to a decline in overall pre-tax wages. This implies that a portion of the money spent on the EITC actually benefits employers of EITC recipients and of other workers competing in the same labor market as the recipients. This means that the EITC (like any other policy that increases labor supply, importantly including welfare work requirements) functions in part as a subsidy to employers of the workers in question. As the target recipients of the EITC tend to be relatively low income, the employer share of the benefit flows to employers of low-skill labor.

One implication is that the minimum wage can be an efficient complement to the EITC, improving the latter’s effectiveness by limiting employers’ ability to capture the credit. This runs contrary to many policy discussions in which minimum wage opponents point to the EITC as a superior alternative. Incidence considerations imply that the two policies are best thought as complements rather than substitutes, and that EITC increases strengthen the case for raising the minimum wage.

How does the Earned Income Tax Credit help the well-being of low-income working families?

Poverty

The EITC is extremely successful as an anti-poverty program. Credit eligibility is concentrated among families whose incomes (after taxes and transfers) would otherwise be between 75 percent and 150 percent of the poverty line, and take-up rates are substantially higher than in many other anti-poverty programs.

The dramatic expansion of the EITC in the mid-1990s was associated with a decline in child poverty rates in the United States (though this was almost completely reversed during the Great Recession). There were a number of causes for this decline—welfare reform and the strong economy of that period among them—but several studies have found that the EITC was an important contributor to the reduction in poverty due to its work incentives. The Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure estimates that the poverty rate was 15.5 percent in 2013, but would have been 18.4 percent without the EITC and Child Tax Credit.

This estimate does not count the extra earnings that EITC recipients have due to their increased work. Hilary Hoynes of the University of California-Berkeley and Ankur Patel of the U.S. Treasury Department find that labor supply effects approximately double the EITC’s anti-poverty effectiveness, and that the mid-1990s expansion reduced the share of families below the poverty line by 7.9 percentage points.

The program’s effect on child poverty is even stronger: The poverty rate for those under 18 years of age was 16.4 percent, but (again ignoring labor supply responses) would have been 22.8 percent without the refundable tax credit. Based on these numbers, the EITC can be credited with lifting 9.1 million people—including 4.7 million children—out of poverty. The effects on total poverty are far larger than those of any single program except Social Security, and the effects on child poverty are the largest without exception. Again, accounting for the program’s effects on employment and earnings would lead to even larger anti-poverty effects.

Children’s educational outcomes

There is robust evidence that the EITC has quite large effects on children’s academic achievement and attainment, with potentially important consequences for later-life outcomes. Gordon Dahl of the University of California, San Diego and Lance Lochner of the University of Western Ontario find that EITC income raises combined math and reading test scores by about 6 percent of a standard deviation per $1,000 received. The EITC test score impacts appear to be larger for boys, children under 12, black or Hispanic children, and for children whose parents are unmarried. Effects of this magnitude are likely to translate into substantially better life outcomes.

There is also evidence of effects on the amount of education obtained, as distinct from achievement on standardized tests. The University of Michigan’s Katherine Michelmore found that a $1,000 increase in the maximum EITC is associated with 18- to 23-year-olds in likely EITC-eligible households being one percentage point more likely to have ever enrolled in college, and 0.3 percentage points more likely to complete a bachelor’s degree. A rough estimate of the present value of a college degree is $1 million, meaning that a 0.3 percent increase in college graduation is worth about $3,000. That means the return is about 3-to-1 for the initial investment—a large effect, especially considering that college graduation rates are not the main intention of the EITC to begin with. Similarly, Day Manoli of the University of Texas-Austin and Nick Turner of the Treasury Department also find that an extra $1,000 of EITC rebate in the senior year of high school increases college enrollment by 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points.

Health

William Evans of the University of Notre Dame and Craig Garthwaite of Northwestern University examine the EITC’s effects on women’s health before and after the 1993 expansion, finding that women reported improved mental and physical health. The expansion also led to sizable improvements in infant and child health. Hilary Hoynes; Douglas Miller of the University of California-Davis; and David Simon of the University of Connecticut find that the EITC expansion reduced the incidence of low birth weight, a widely used indicator of poor infant health.

What are some proposed modifications to the Earned Income Tax Credit?

Changes within the same basic structure

There have been a number of proposals to expand the EITC either as a whole or for particular groups. Recently, these discussions have centered on temporary EITC expansions (a larger credit for three-child families and an extended schedule for married couples) introduced in 2009, which are due to expire in 2017.

One area of concern has been incentives for non-custodial parents, or parents who do not have primary custody of their children. A focus in this area has been to create incentives for the payment of child support, by allowing these parents to receive the credit but conditioning it on the payment of child support. Non-custodial parent credits have recently been implemented in New York and Washington, D.C. An evaluation of the New York program by Austin Nichols, Elaine Sorenson, and Kye Lippold at the Urban Institute found increased work and payment of child support among non-custodial parents eligible for the credit.

A more consequential change would be to expand the EITC for childless workers more generally. This has attracted support of late from President Obama as well as prominent Republicans (notably Representative Paul Ryan (R-WI), now Speaker of the House). President Obama’s most recent proposal, part of his 2016 budget, would double the childless worker credit and extend the age ranges at which taxpayers are eligible. Work I did earlier this year with Hilary Hoynes examines the distributional impacts of the Obama proposal and of a more aggressive proposal that would bring the childless EITC to parity with that available to families with children.

Gordon Berlin, president of MDRC (a non-profit social policy research organization), proposes a more radical modification in the structure of the EITC. He would make EITC eligibility depend on individual earnings, without regard to marriage or children. This would eliminate the second worker penalty, alter marriage incentives, and generate tens of billions of dollars in additional credit payments, mostly to married couples. The expansion of the plateau phase for taxpayers married filing jointly during the 2000s have made the proposal cheaper to implement, but budgetary concerns make implementation of the proposal unlikely. A somewhat less aggressive proposal comes from the Hamilton Project’s Melissa Kearney and Lesley Turner, who propose a secondary earner deduction that would reduce but not eliminate the second worker penalty in the EITC.

There are also several recent proposals for a new EITC aimed exclusively at workers with a documented work-limiting disability, aimed at increasing employment of those with disabilities and thereby reducing strain on the Social Security Disability Insurance trust fund. Two studies done by Jun Huang of Columbia Business School and Maximillian Schmeiser at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, as well as Boston College’s Matthew Rutledge, examine the likely impact of EITC expansion on people with work-limiting disabilities and find an increase in labor force participation among workers with resident children compared to those without.

Administration of the Earned Income Tax Credit

Many EITC recipients hire tax preparers to help file their taxes. In fact, the IRS estimates that 15 million EITC recipients used paid tax preparers in 2013, and one study estimates total tax preparation fees at $2.75 billion. Until recently, many of these for-profit preparers were also in the business of marketing short-term loans (known as refund anticipation loans) against eventual EITC refunds, at very high implicit tax rates.

Recent bank regulation efforts have largely eliminated refund anticipation loans, although there are still other financial products designed to capture a portion of the tax refund. The IRS encourages claimants to simply write “EITC” on their tax returns rather than attempting to calculate it, presumably in part to simplify returns so that recipients do not need to engage preparers. Moreover, not-for-profit tax preparation services exist in many areas. Nevertheless, the high cost to recipients of tax filing services remains a concern.

A second administration issue relates to the EITC’s arrival as a lump-sum payment, months after the period that it nominally covers. It seems clear that the EITC would be more effective in supporting low-income families if it could somehow be delivered more evenly throughout the year. Until 2011, EITC recipients could choose to receive a portion of their credit with each paycheck rather than as a lump sum at tax filing time via the Advance EITC program. But take-up of this option was very low—only 1 percent to 2 percent of EITC claimants—leading to its cancellation. The reasons for this are not well understood. Thus, while there is the desire to change the method of payment, I am not aware of workable proposals to do so.

Conclusion

The Earned Income Tax Credit has become the centerpiece of the U.S. safety net, surpassing all other transfer programs (save perhaps Social Security) in the number of beneficiaries, total expenditures, or poverty reduction impacts. The evidence clearly indicates that it is a remarkably successful program, with important impacts on recipients’ labor supply and health and on their children’s health and educational outcomes.

Appendix

Photo of mother and daughter, veer.com