This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

This week we published the third installment in our “Equitable Growth in Conversation” series. In this interview, Ben Zipperer talks to David Card and Alan Krueger about advances in empirical techniques in labor economics among other topics.

Increasing concern about a lack of competition in the U.S. economy has most people thinking about how to reduce consolidation among companies. But we shouldn’t ignore the importance of competition in the labor market.

U.S. labor force participation has changed quite a bit over the past 40 years. But as workers have entered and exited the labor force, where have they ended up? And how have these trends changed across the income distribution? Check out our interactive graph to find out.

After being in the wilderness for a few decades, the idea of a universal basic income is making a bit of a comeback. While there aren’t a lot of recent research ideas, it’s worth thinking about some of the potential effects of the program.

In their interview, Card and Krueger talk about advances in techniques to draw out the causal effect of programs and economic shocks. These advances are important and quite interesting, but there is no gold standard when it comes to the techniques.

Links from around the web

Productivity growth has been quite weak in the wake of the Great Recession. Toby Nangle argues that the lack of strong productivity gains may mean the global economy faces a “new impossible trinity”—unless stronger labor bargaining power actually starts to boost productivity. [ft alphaville]

The decline of the middle class in the United States has a number of causes. But the decline of government jobs in recent years looks to be a significant contributor, especially for the black middle class. Annie Lowrey dives into the subject. [nyt magazine]

When it comes to U.S. government debt, the public and policymakers are usually concerned that there’s too much of it. But Narayana Kocherlakota makes a good argument that there should actually be more government debt to help the global economy. [bloomberg view]

The source of low measured productivity growth in the United States is far from clear. And there are a number of hypotheses for why it’s happening. Neil Irwin runs through three scenarios: the depressing, the neutral, and the happy. [the upshot]

Gross domestic product, probably the most cited economic statistic, has come under attack in recent years. A number of researchers, policymakers, and advocates have argued that the statistic is outdated, doesn’t accurately represent changes in living standards, and doesn’t measure economic output well. The Economist joins the skeptical choir. [the economist]

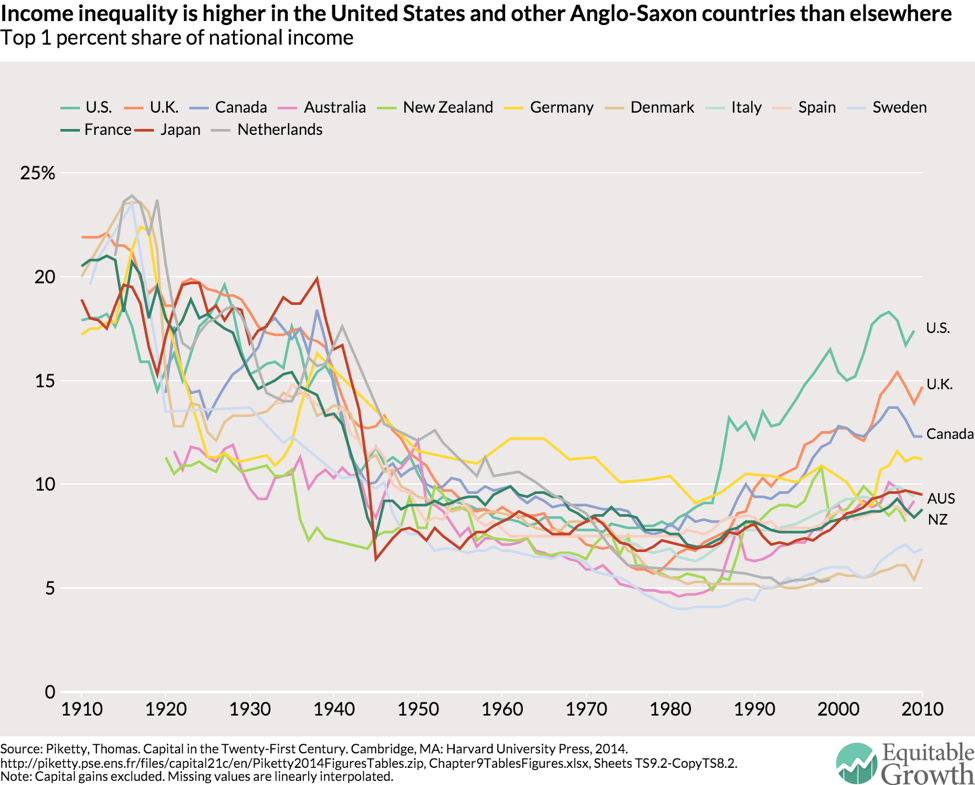

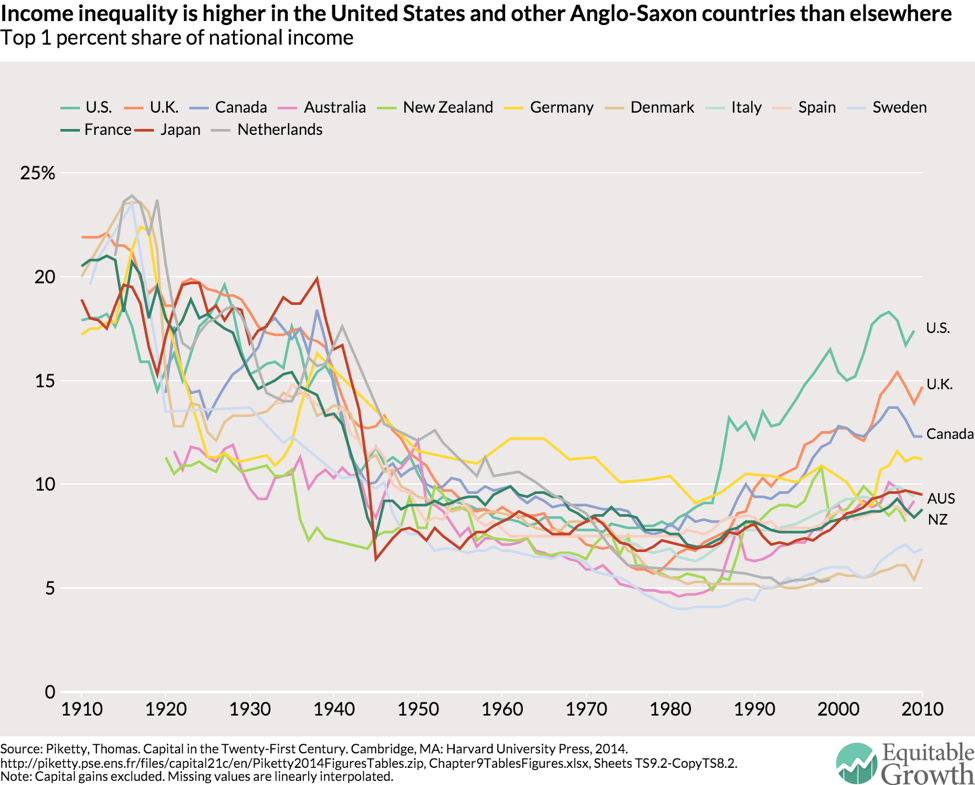

Friday figure

Figure from “What explains the rise in income inequality at the top of the income distribution?” by Matt Markezich