The U.S. unemployment rate has been at or under 5 percent for more than six months. But even though that number is close to many estimates of the long-run unemployment rate, neither inflation nor wage growth has picked up considerably, despite expectations that they would.

To paraphrase an influential figure of the last era of full employment, what’s the deal with that? Why hasn’t accelerating—never mind strong—wage growth appeared yet? There are a number of possibilities, each a likely contributor to the failure of wage growth to pick up. The challenge is figuring out which are the largest contributors.

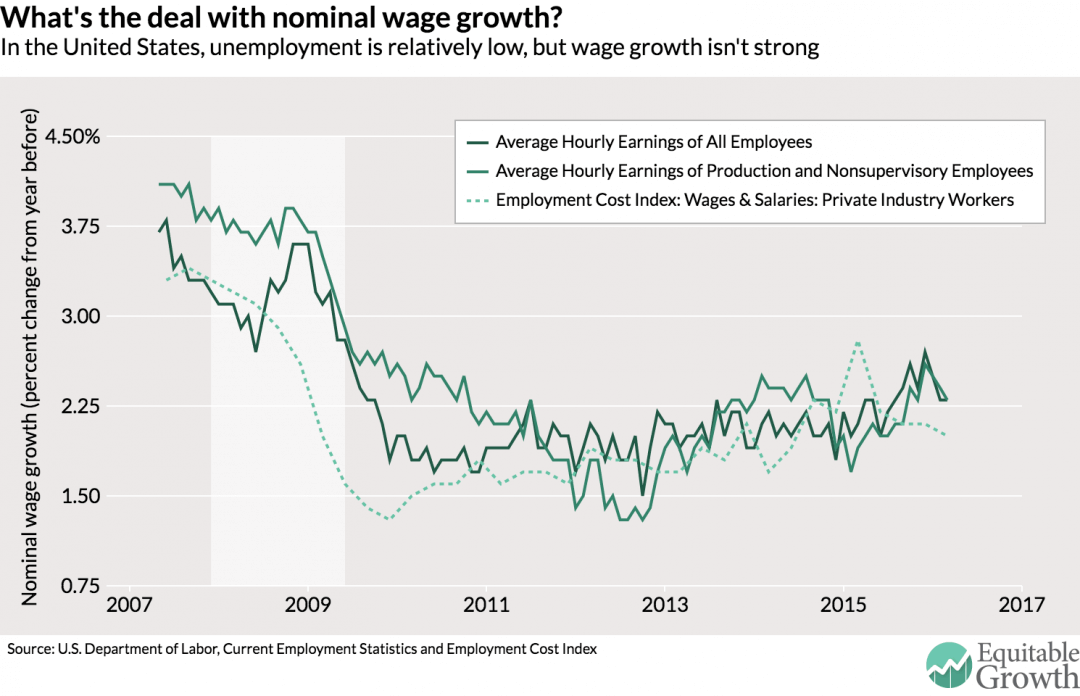

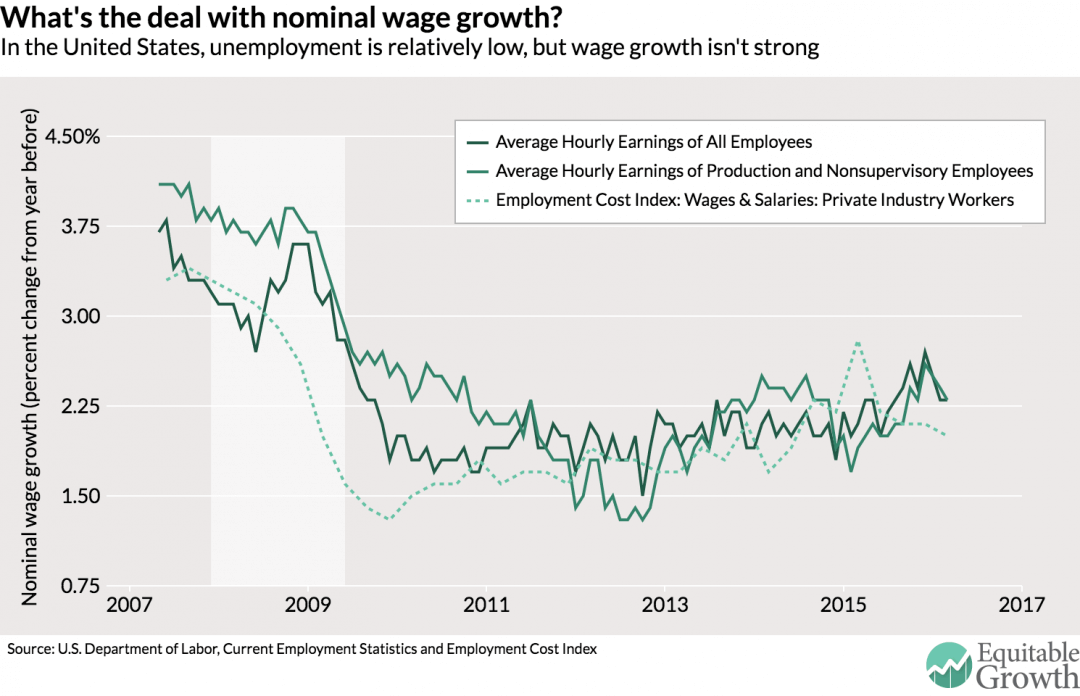

But first, a quick review of the state of nominal wage growth. After a period of seemingly being locked in at 2 percent, nominal wage growth in the United States appeared to pick up in 2015 by a number of measures. But as reflected in Figure 1, it looks like nominal wage growth has since halted its advances. Consider the Employment Cost Index, which seemed to show the first signs of accelerating wage growth in early 2015. The latest data for the first quarter of 2016, released this past Friday, show an annual growth rate of only 2 percent for private-sector workers. Nominal wage growth seems slightly higher according to the Current Employment Statistics data released every month with the jobs report. But both measures only show annual growth of about 2.3 percent—a decline from prior months.

Figure 1

Now let’s look at the possible culprits.

First, a 5 percent unemployment rate may not mean what it used to mean. With the long-term decline of the U.S. labor force participation rate, the unemployment rate may be slightly overstating the health of the country’s labor market. Measured by the employed share of workers ages 25 to 54, the labor market has a long way to go before it hits a level usually associated with strong wage growth.

Or perhaps wage growth is behaving strangely because inflation is acting strangely. That’s an argument put forward by Adam Ozimek of Moody’s Analytics, who points out that inflation acted in some unprecedented ways over the course of 2015. Overall inflation, measured by the Consumer Price Index, actually went below zero during some months last year. The last time that happened outside of a recession was in the 1950s. Low inflation has an impact on wage growth, because employers will be less willing to pass along wage hikes to prices, and employees will need less of a wage increase as their real wage growth has been higher.

A third argument is that compositional effects are to blame for the lack of acceleration in measured wage growth. Several economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco have argued that low measured wage growth is due in part to low-wage workers moving into full-time employment. This means that while already-full-time employees are seeing rising wages, that growth is masked by the entrance of lower-earning workers. And the apparent stall in the Employment Cost Index disappears and a clearer upward trend emerges once occupations that pay quite a bit in bonuses are taken out of the calculation.

Of course, all three of these stories as well as others could be true—they’re not mutually exclusive. The relative importance is key. As I’ve written before, the compositional effect has some truth to it, but measures of wage growth looking at only full-time employment seem to indicate only the early stages of a tightening labor market, not its end stage. And while low inflation may mean employers are hesitant to raise prices, research indicates that wage increases are less likely to pass through to overall price increases so that concern might be overblown at this time.

It seems likely then that the labor market just isn’t strong enough to trigger broad-based, strong, accelerating wage growth. Five percent just isn’t what it used to be anymore.