This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The ideas of turn-of-the-last century Swedish economist Knut Wicksell have suddenly become quite relevant for monetary policy. The Fed is currently thinking through how high interest rates have to go before they can stop hiking. Figuring out the natural rate of interest is key to that endeavor.

The last several years have seen a rethinking in the benefits of free capital flows between countries. They may play a role in inflating speculative bubbles and push down short-term natural interest rates. In other words, it may contribute to secular stagnation.

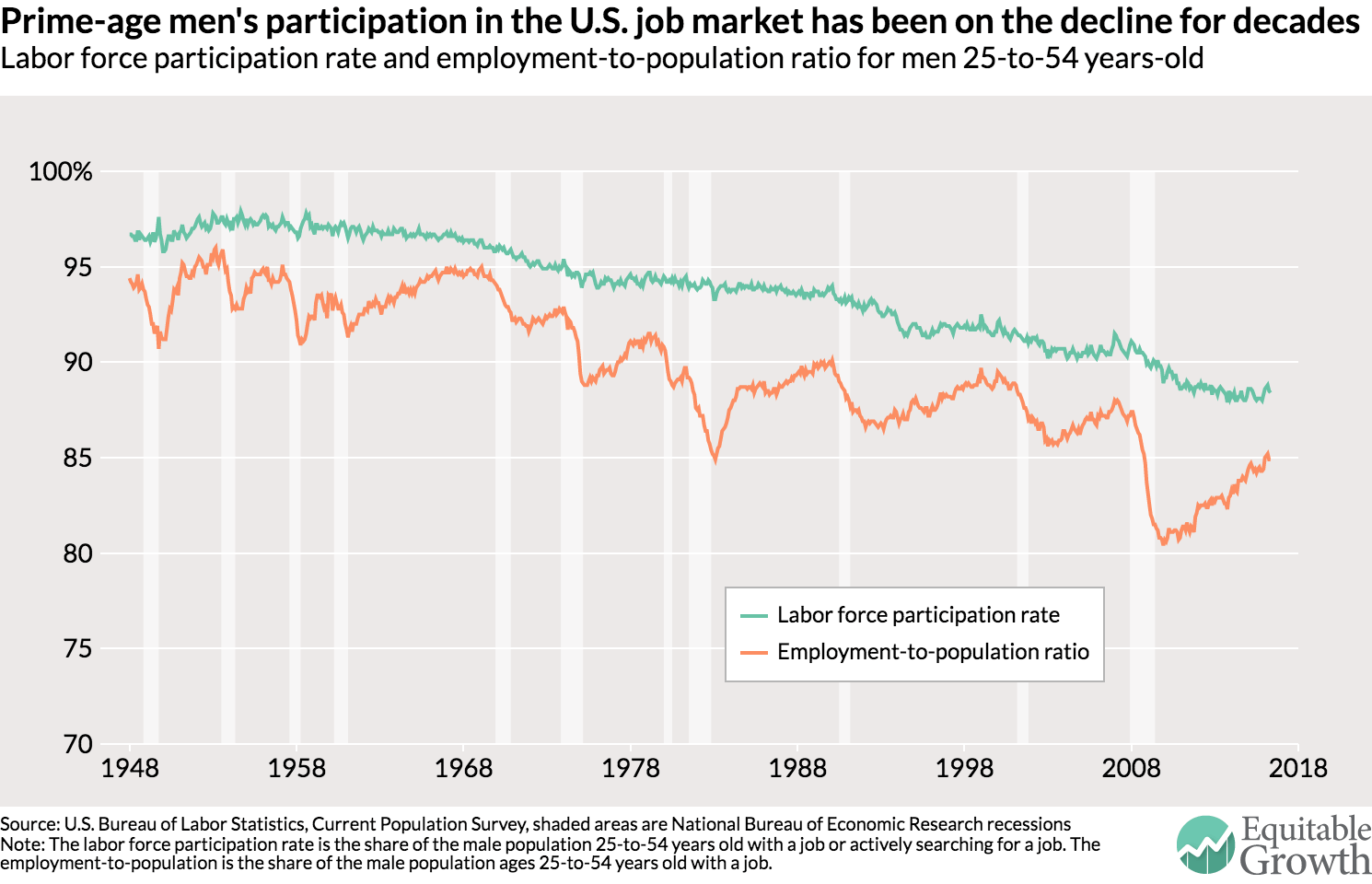

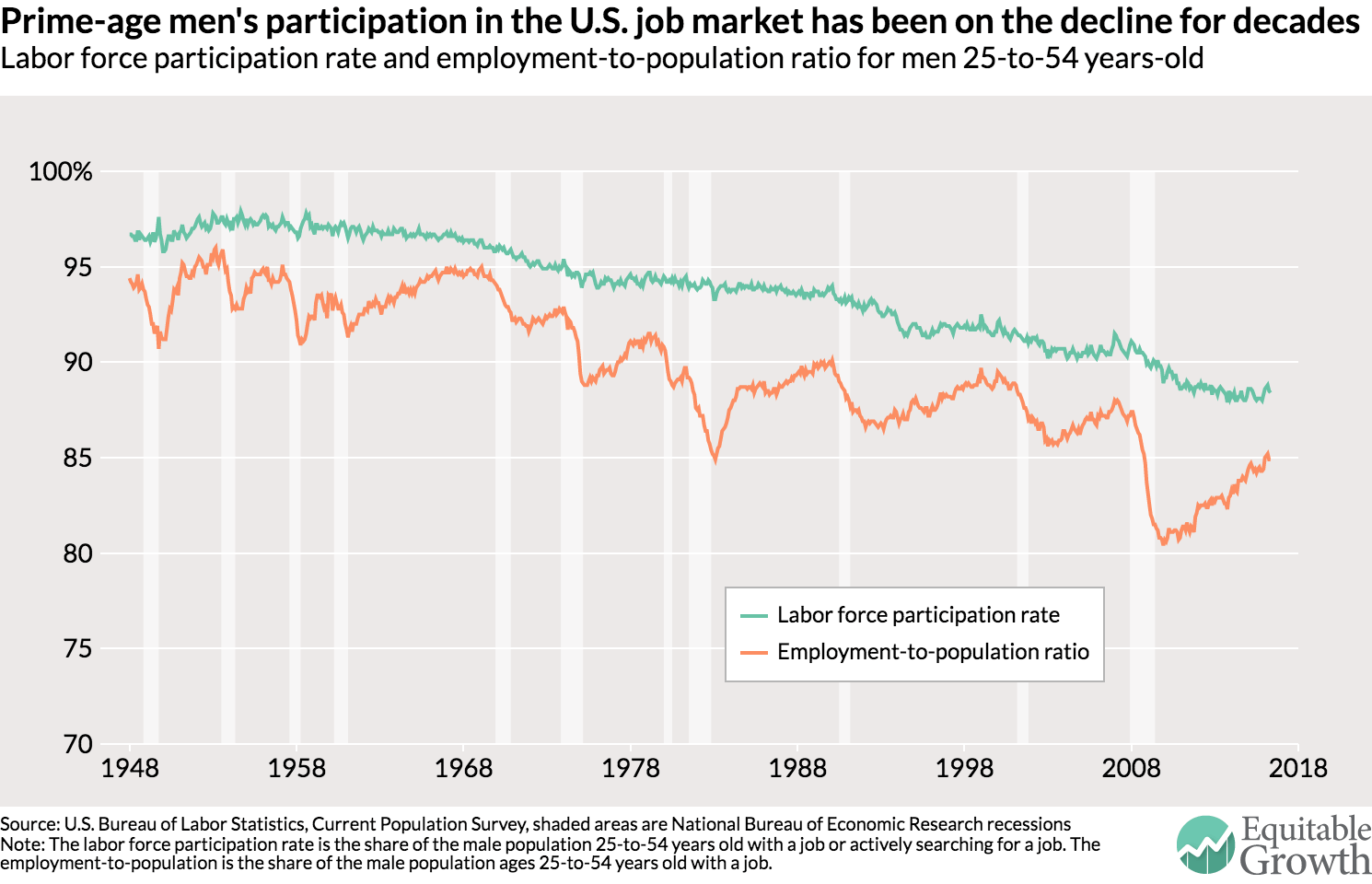

The share of prime-age men in the United States with a job or actively searching for one has been on the decline for more than 50 years. What’s behind the decline? Evidence points to a decline in demand for labor from less-educated men.

Programs such as unemployment insurance are designed to insure workers against some of the pains of losing a job. But unemployment insurance and other so called automatic stabilizers also help boost economic growth during downturns by putting money in the hands of those who will spend it most readily.

Increased consolidation of health care providers has been touted as a way to increase efficiency in the health care industry. But there are downside as well, Nisha Chikhale writes, including higher prices.

Links from around the web

The Great Recession ended seven years ago this month and yet portions of the United States still have not recovered to the employment rates they had in 2007. And these areas of the country don’t seem likely to reach that level for years. Ana Swanson writes about a paper by economist Danny Yagan at the University of California-Berkeley on this troubling trend. [wonkblog]

What’s behind the rise in wealth inequality? Scottish economist and Nobel Laureate James Mirrlees argues that the random nature of investment returns is a significant cause. And that this fact supports the notion that policymakers might want to tax very high rates of returns on capital to reduce wealth inequality. [contemporary economic policy]

Twenty years ago. U.S. policymakers radically reformed the federal welfare system, then known as Aid for Families with Dependent Children. After two decades with the new Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program in operation, has the replacement program been a success? Dylan Matthews investigates. [vox]

Does slower productivity growth in the United States mean that the interest rates will necessarily be low in the future? The former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, Olivier Blanchard, says no. [piie]

A strange discrepancy in data series about job openings—the U.S. government-created Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey and the Conference Board Help Wanted Online series – has appeared in recent months. Given that the Conference Board’s data goes into a Federal Reserve measure of the labor market, this divergence matters. And it seems to be, in part, because Craigslist has been raising prices. [fed notes]

Friday figure

Figure from “What’s behind the decline in male labor force participation in the United States?” by Nick Bunker