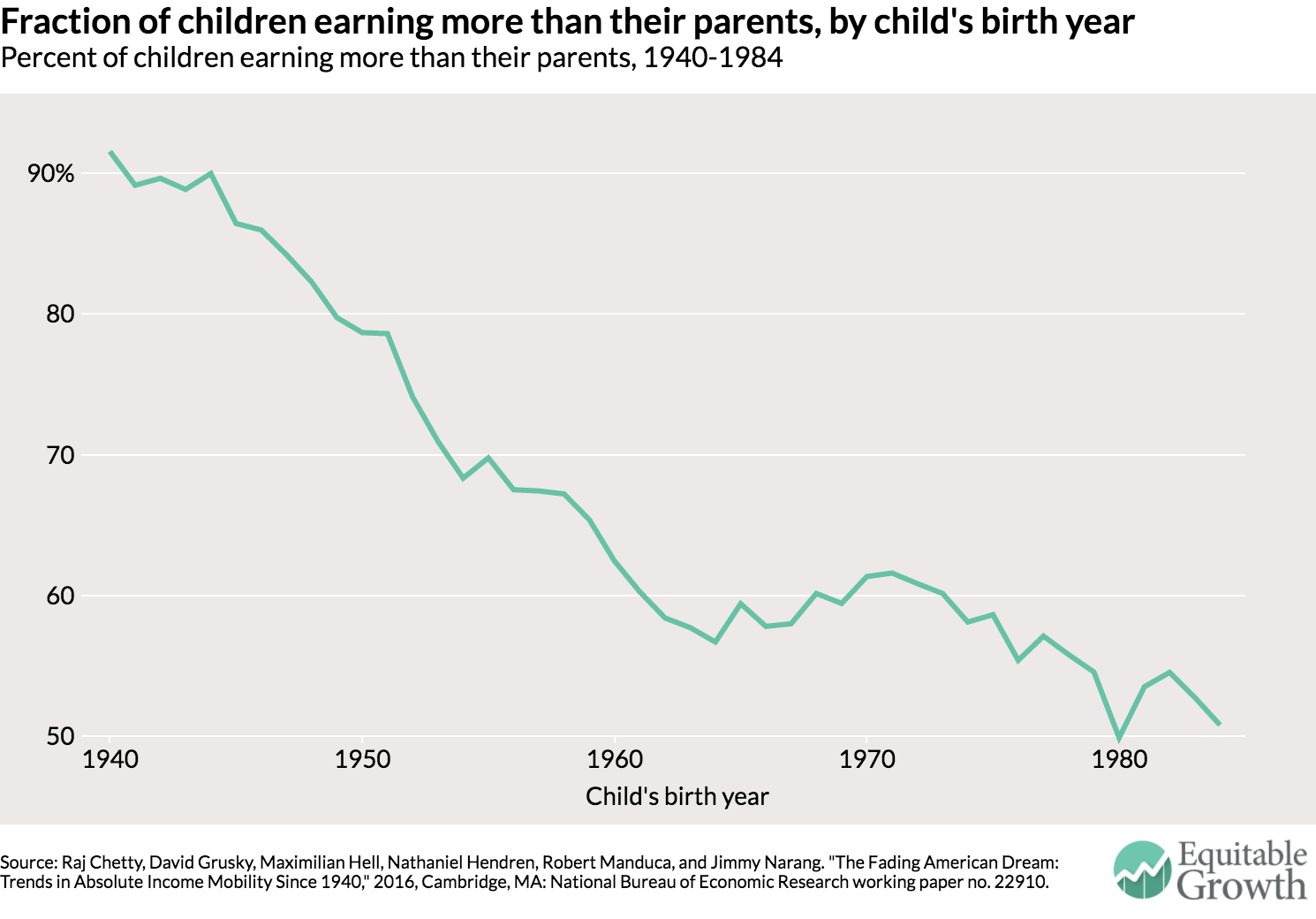

A new study released today by several researchers, led by Raj Chetty of Stanford University reveals a large and significant decline in economic mobility in the United States. The paper shows a precipitous decline in the probability that a person will earn more than their parents, what researchers call “absolute mobility.” Specifically, Chetty and his coauthors look at income levels when a worker is 30 years old, for both parents and children. (For more details on the paper, check out the authors’ summary for Equitable Growth as well as a piece on the new paper from David Leonhardt at the New York Times.)

The paper by Chetty and his co-authors has many interesting findings that researchers and policymakers will certainly dig into. For now, let’s examine the role of relative mobility—the movement up and down the income distribution—in determining absolute mobility. The results of the paper shows a path toward boosting mobility that points toward stronger, more equitable economic growth

One way to think about absolute mobility is that depends on two trends. First, how quickly has income grown at different points in the income distribution for those 30-year-olds from when their parents were 30? Second, how likely it is for the younger generation to be at a point in the income spectrum that is different than their parents? We call the second “relative mobility” because a child could move up or down the income spectrum relative to their parents, but still earn more or less than their parents. We can think absolute mobility is a function of relative mobility, the strength of income growth, and the distribution of income growth.

Whether absolute mobility is higher or lower depends on where the child ends up and how income growth has been at that position. When there is a low level of relative mobility, a child’s absolute mobility is essentially tied to the rate of income growth at their parent’s income level. When there is more relative mobility, it’s less tied.

Previously, Chetty and his co-authors in another project did the work of figuring out the trends in relative mobility for the United States going back to children born in the early 1970s. What they found is that relative mobility hasn’t changed that much—that a parent’s income position has the same relationships with their children’s as it did 40 years ago. With this information in hand, the authors of this new paper can directly calculate absolute mobility for groups of children born after the early 1970s. They find that it’s been on the decline since that time.

But it’s the data before the 1970s where their story gets even more interesting. The researchers have data on income growth going back to the cohort born in 1940, but no data on relative mobility for that era. Any calculation of absolute mobility would have to make assumptions about the levels of relative mobility during the years between 1940 and 1970.

Yet Chetty and his coauthors show that regardless of the assumption one makes about relative mobility during this time, absolute mobility fell. They calculate what absolute mobility would have been for children born in 1940 for every possible level of relative mobility. The result is that absolute mobility would have ranged from 84 percent to 98 percent, depending upon the level of absolute mobility. Regardless of the level of relative mobility, the average worker had at least an 84 percent chance of earning more than their parents. That entire range is well above the level of observed average absolute mobility for the generation born in the early 1970s of about 60 percent.

Why does relative mobility not seem to matter for the trend in absolute mobility for the generation born in the 1940s? Well, the level of income growth was so high and broadly shared during the period between 1940 to 1970 that almost all positions on the income distribution of 1970s were richer than those in the 1940 distribution. A worker could stay at, for example, the 20th percentile of income like their father and still see absolute mobility rise because overall income growth in the United States was so strong and equitable.

A worker born in the 1940s could end up pretty much anywhere in the 1970 income distribution as a 30-year-old and have a very good chance of having a higher income than their parents. Strong, equitable growth resulted in high levels of mobility regardless of the levels of relative mobility. These results indicate that while higher levels of relative mobility may be a good thing in and of itself, it’s not necessary for higher levels of absolute mobility. If we want to insure rising living standards for most Americans, strong and equitable growth across the income distribution seems the best path forward.