When the U.S. Senate begins hearings on the appointment of Andrew Puzder—President Trump’s choice to head the Department of Labor—it is important to consider his qualifications for leading a federal agency tasked with overseeing and enforcing the nation’s labor laws. Beyond his experience as chief executive of CKE Restaurants Holdings Inc., the privately held owner of several fast-food chains (among them Carl’s Jr.), Puzder has been an outspoken critic of labor regulations including minimum wage laws, overtime protections, and health and safety regulations.

Through the record of his op-eds, lobbying work on the behalf of the National Restaurant Association, and blog posts, policymakers and the public can get a clear picture that some of his opinions and beliefs are simply at odds with the facts or at the very least ignorant of recent evidence. In this issue brief, I compare some of Puzder’s widely publicized claims about the very labor regulations he would be tasked with upholding and enforcing, should he be approved by the Senate.

Download File

U.S. Labor Department appointee, the minimum wage, and labor markets

Read the full PDF in your browser

Minimum wage

Claim: “Instead of creating a living wage, the fight for dramatic minimum-wage increases could leave millions with no wage at all.”

Puzder has opined about the consequences of raising the minimum wage more than any other topic. In this statement above and others like it he claims that even moderate minimum wage increases will lead to massive jobs losses. Rather than offering credible academic evidence, he typically bases these claims on simple platitudes such as “make something more expensive and employers will use less of it.”

Yet there is an emerging consensus among economists that moderate increases in the minimum wage have no detectable negative impact on employment. This finding stems from research that examined every state-level minimum wage increase since the early 1990s and compares what happens to employment in low-wage sectors such as restaurants and among teenagers in counties that lie along a state border (where the minimum wage went up) versus counties on the other side of the state border. This careful research design amounts to an apples-to-apples comparison and does not make the mistake of comparing employment trends across states that have dramatically different population trends and economic bases. Several additional papers find similar results.

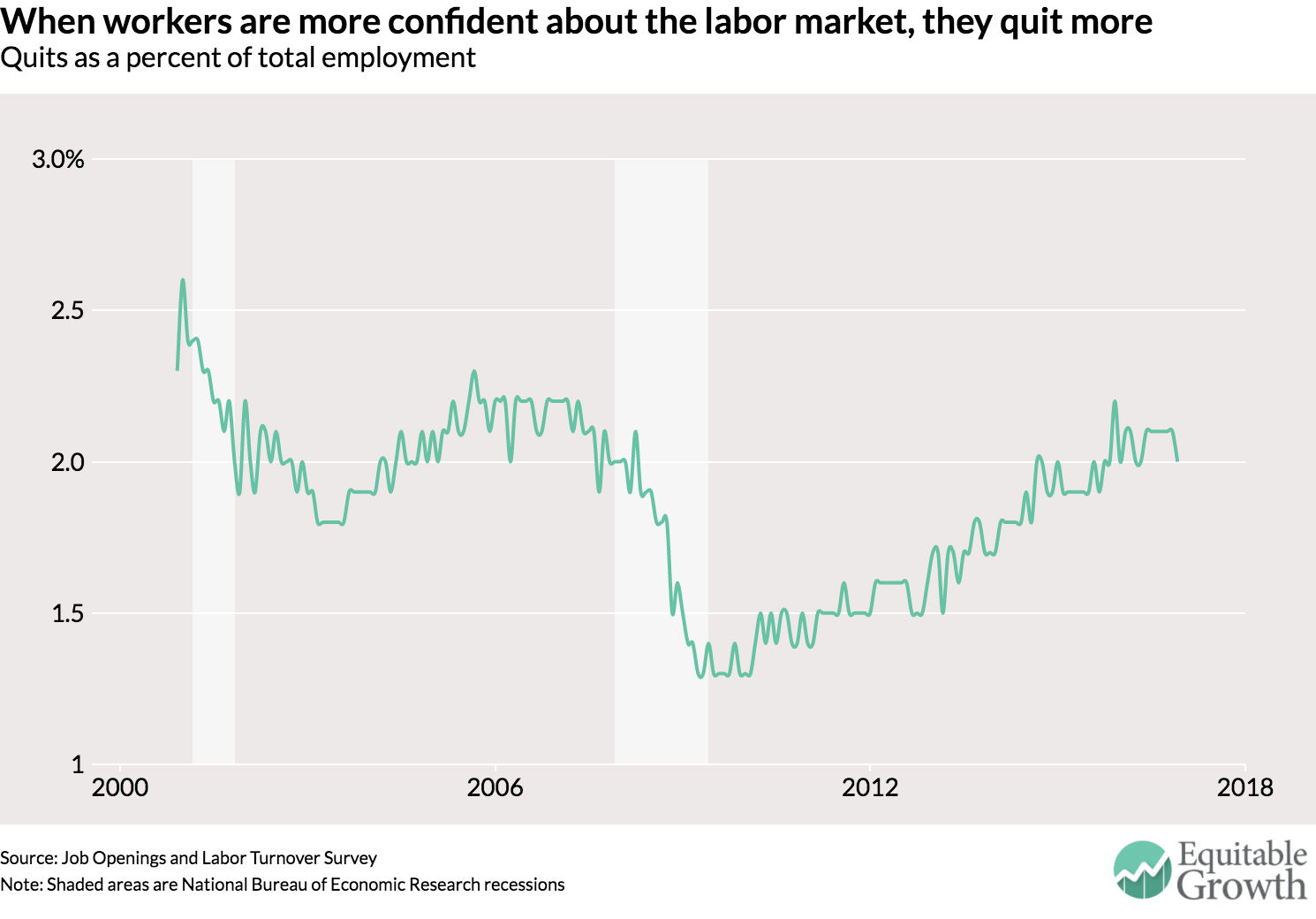

Similarly, a host of economists have offered more realistic models of the labor market—models that recognize the natural dynamism of the so called labor-matching process between workers and employers. One of the key reasons that economists believe that moderate minimum wage increases do not lead to job losses stems from the observation that the typical textbook model of the labor market where employers are simple price takers and instantaneously match perfectly observable supply and demand curves hardly approximates the “real world.” Indeed, under these same models, a minimum wage increase actually kills job vacancies rather than jobs because employees stay longer in their current positions rather than moving to other jobs across the street.

Instead, workers value their jobs more under a higher wage and put in more effort, resulting in higher productivity and a lower firing rate. Empirical research bears this out, as turnover-rates fall dramatically in the face of a minimum wage increase. Ultimately, Puzder’s views on the minimum wage do not take into account new and important credible economic research.

Healthcare

Claim: “The evidence that Obamacare is having a negative impact on hiring is unequivocal, abundant and consistent with common sense.”

Puzder also has written extensively about the costs of the employer-mandate component of the Affordable Care Act. Not surprisingly, he opposes this regulation, basing his views on the burdensome costs that restaurant owners and other low-wage employers will have to pay. Yet in the course of his arguments he misrepresents some basic facts about employment data that are published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, which is part of the Department of Labor that he seeks to lead.

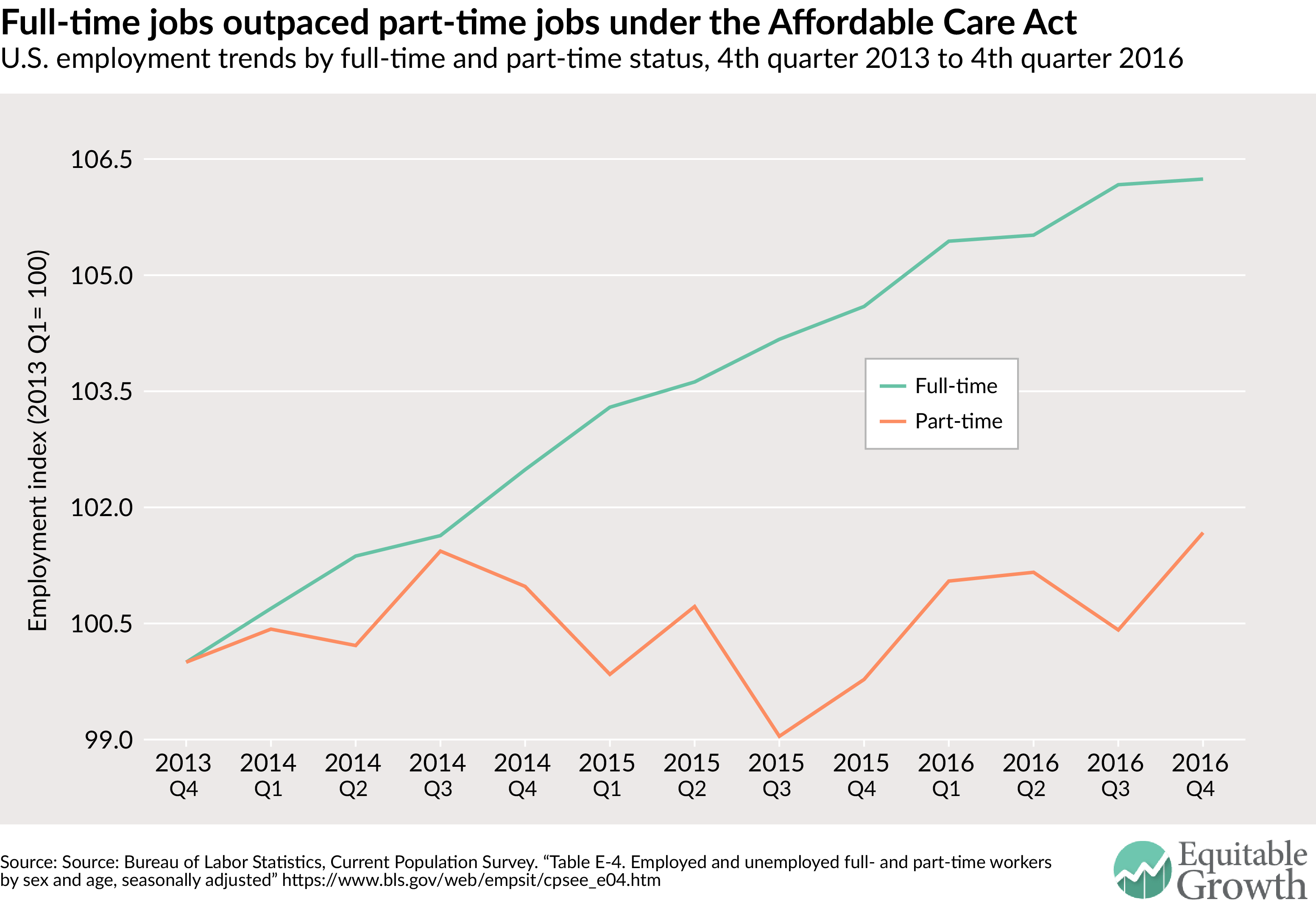

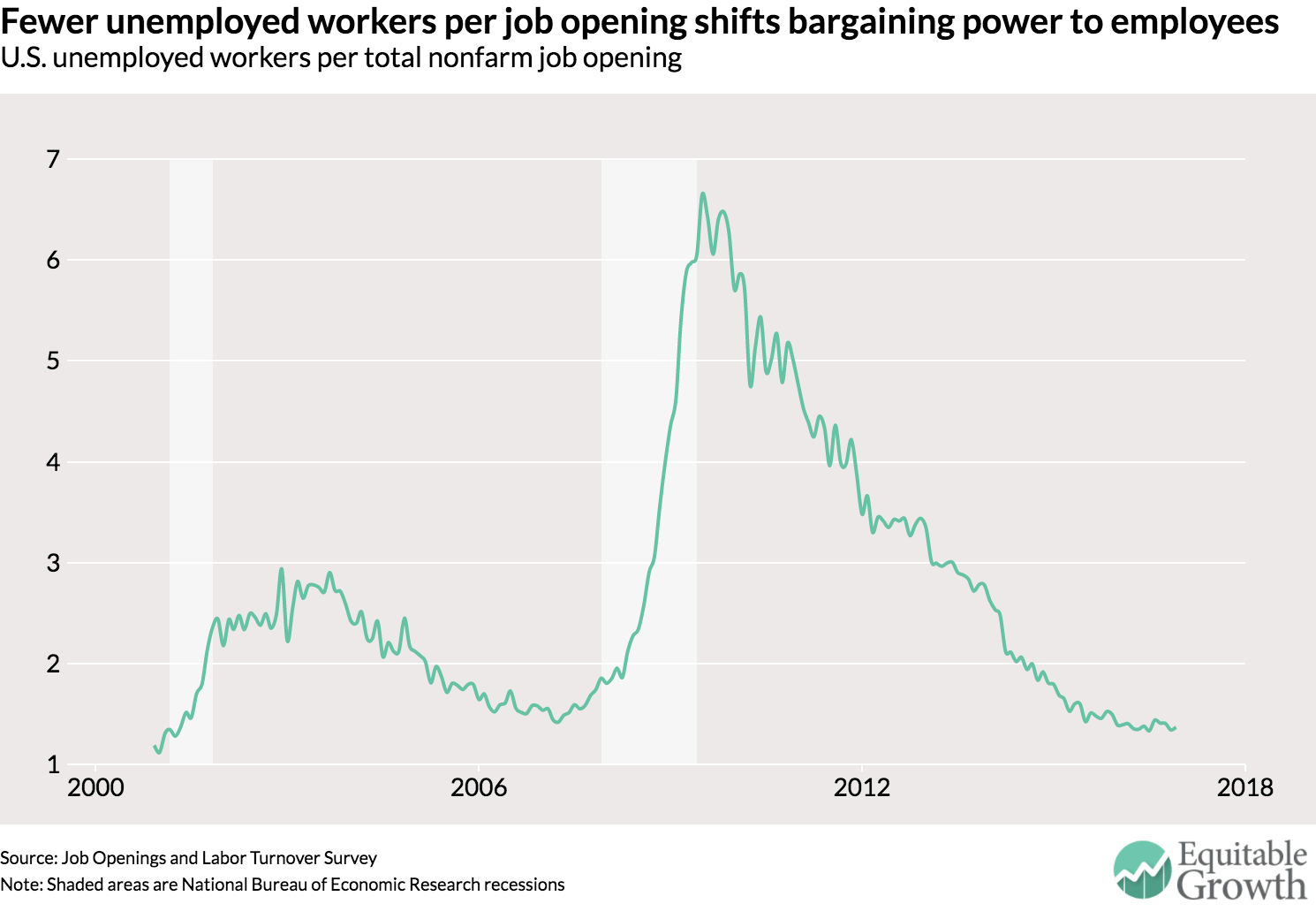

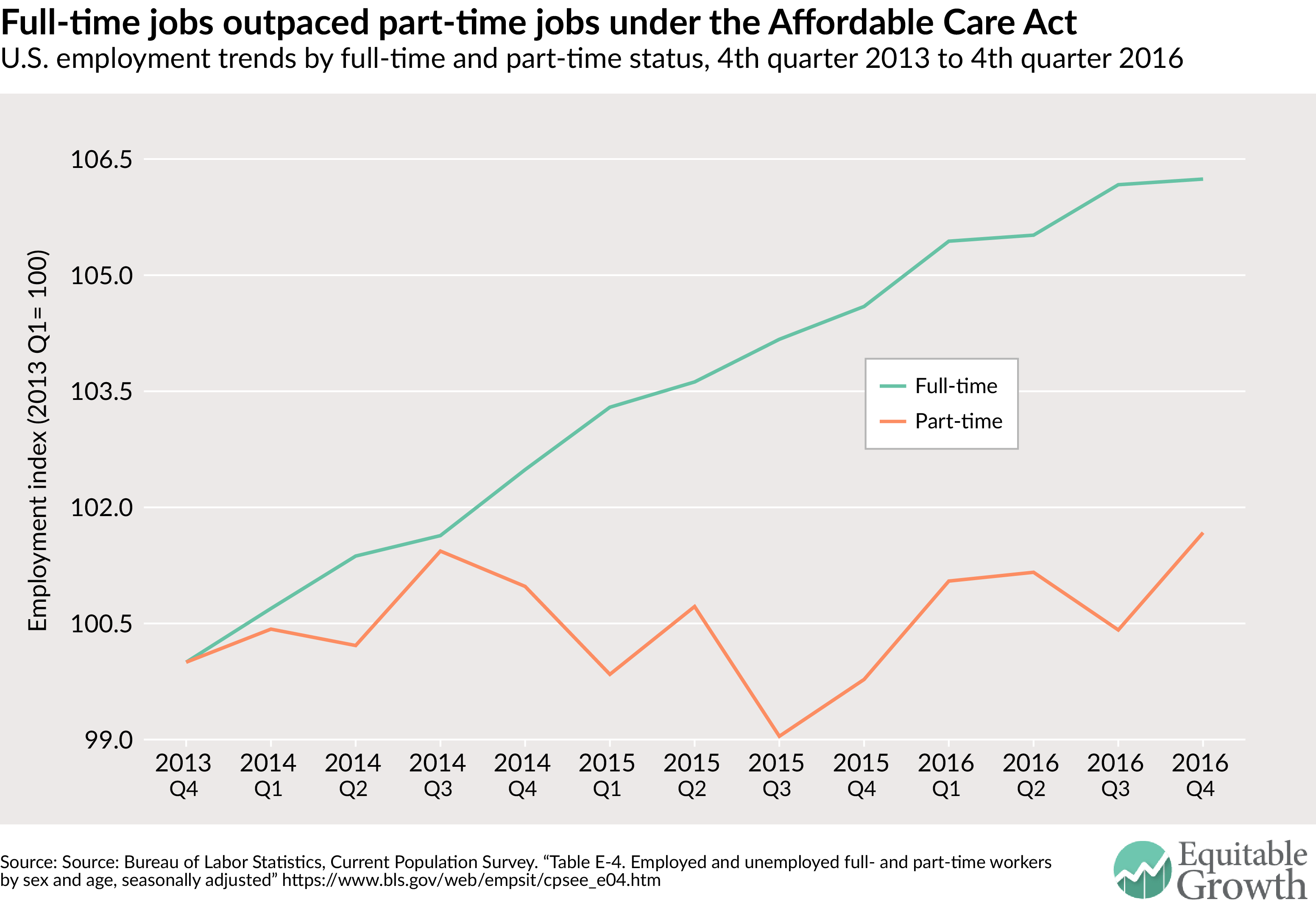

Puzder erroneously claims that the vast majority of large employers are switching from hiring full-time workers to part-time workers to avoid the 30-hour-per-week threshold for the employer mandate to provide heath care under the Affordable Care Act. He looks at one six-month period of BLS data in 2014 and concludes that the only new jobs added were part time jobs. This claim seemed so unfounded that I simply looked at the record of job creation since the last quarter of 2013—the quarter in which the so-called “look back period” could plausibly begin before the mandate actually took effect at the beginning of 2014—through to the end of 2016. The data show just the opposite of what Puzder claims. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

More specifically, based on a basic interpretation of this data, we can see that contrary to Puzder’s claim, the pace of job creation was faster for full-time workers than part-time workers, growing 6.2 percent since the 4th quarter of 2013, compared to 1.7 percent, respectively. If employers were sharply shifting toward part-time work, then we would expect to see the opposite trend.

Even though the data betray the point the Puzder was trying to make, he still bases his opposition to the employer mandate based on a faulty and simplistic understanding of the labor market. He views workers as perfectly interchangeable units that lack the possibility for learning on the job or improving productivity. He writes:

“The logic for businesses is simple. If you have three employees working 40 hours per week they will produce 120 labor hours. Five employees working 24 hours per week also produce 120 labor hours. Employers must offer the three full-time employees health insurance or pay a penalty. They have no such obligation to the five part-time employees, making part-time employment less costly.”

One reason why employers haven’t shifted completely away from full-time work is that full-time workers tend to be better, more experienced workers who, in return for more hours, are ultimately more productive.

Recent research in the very industry Puzder bases his expertise on bears this out. In a recent paper, I compared the labor practices of full-service restaurants in two metropolitan regions with vastly different labor regulations—San Francisco—which has a $15 minimum wage, an employer healthcare mandate, and paid sick leave—and the Research Triangle in North Carolina, where no local mandates are allowed. Based on interviews with restaurant owners and managers from a variety of sizes and price levels, several things stood out.

First, employers in San Francisco conducted more careful searches for highly skilled employees who invested in their own training and were ultimately more productive. Employers there were more likely to talk about their workers as professionals, rather than replaceable units. Turnover rates in San Francisco in the restaurant industry were markedly lower than in North Carolina as a result. Second, many employers in North Carolina, who are allowed to paid tipped workers a wage as low as $2.13 per hour, built a business model that accepts an extremely high turnover rate and invests little in improving worker productivity. Moreover, restaurant managers in North Carolina were more likely to view workers as disposable and easily replaceable.

The upshot: policymakers need to consider more carefully Puzder’s understanding of at least these two aspects of his prospective job heading up the Department of Labor—the importance of the minimum wage for broad-based wage growth in the U.S. economy, the very basic evidence about the impact of workers’ benefits on the creation of full-time and part-time jobs, and the importance of higher wages and benefits on economic productivity and employer profits.

—T. William Lester, Associate Professor of City and Regional Planning, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) yesterday

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) yesterday