The rich are different from you and me. They have different consumption baskets.

At least that is the tentative conclusion that some scholars are making in their recent research on the differences in consumption and prices across the U.S. income distribution. Differential inflation rates might not sound like the most exciting topic in the world, but differences in changes in prices and how these differences would impact the level of inequality, the relative gains from increased international trade, and the value of government transfer programs are meaty topics.

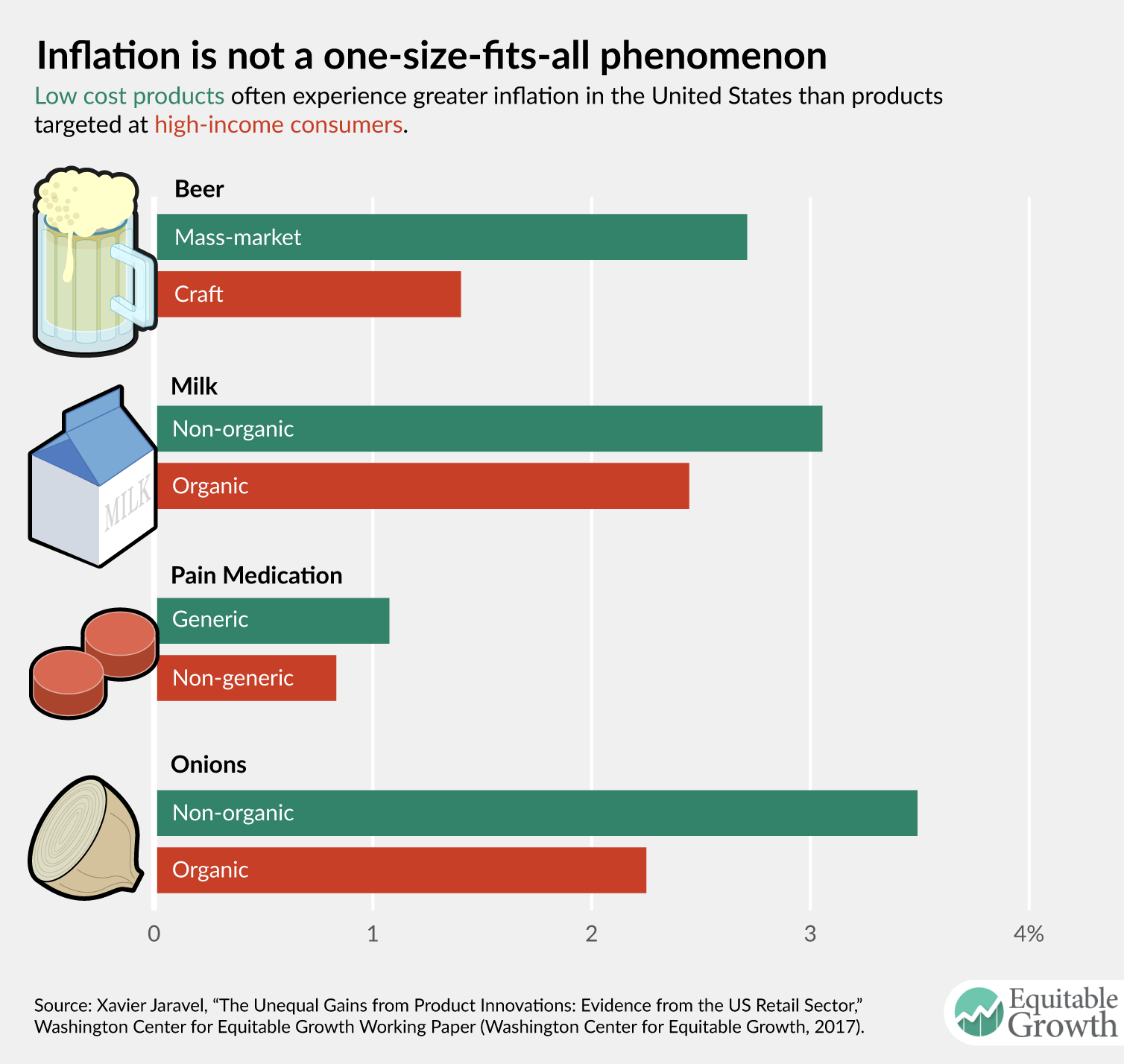

In a paper released today as part of the Equitable Growth working paper series, Stanford University post-doctoral fellow Xavier Jaravel looks at how changes in the income distribution affect differences in product innovation. In other words, Jaravel wants to see if more income at the top means more innovation in products that high-income people buy. He ends up finding that’s exactly what happens, with the result being an inflation rate for high-income households about 0.65 percentage points per year lower than for low-income households.

Another paper, released by the National Bureau of Economic Research earlier this year finds very similar results. Looking at similar data to Jaravel, Benjamin Faber and Thibault Fally of the University of California, Berkeley find a significant difference in the kinds of goods purchased by households in the top 20 percent by income versus those in the bottom 20 percent. Households in the top one-fifth consume more goods from large companies. High-income households tend, for example, to buy more brand name goods than low-income households. The authors say this happens because high-income consumers value higher-quality goods, and large firms can produce a large amount of high-quality goods more cheaply than smaller firms.

This difference ends up having some relevance in certain situations. If income starts flowing more toward high-income households, for example, then companies will have an incentive to increase the quality of their goods. Since larger firms are better at quality production, the prices at large firms will be relatively lower. This would mean that the inequality of inflation-adjusted income would be even larger due to a lower inflation rate for high-income households.

Similarly, if international trade is liberalized, more international competition boosts the share of imported goods, which, in Faber and Fally’s model, will tend to be from higher-quality larger firms. The result is that the richer gain more from the price declines brought on from trade, making the consumer benefits from international trade less progressive than previous studies had indicated.

If both these papers are generally correct, then the differences in inflation also have another implication. If the prices faced by those at the bottom and middle of the income distribution grow faster than the average prices reported in the Consumer Price Index or the Personal Consumption Expenditure price index, then U.S. government safety-net programs should grow at a faster pace. The growth of many programs is tied to overall inflation measures, so they may not be keeping up with the pace of inflation that low-income households actually experience.

Of course, such adjustments should wait until we have far more evidence on this possibility. Given the numerous ways that inequality in inflation could influence our understanding of the economy, this is evidence policymakers and researchers should be very interested in.