This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Three years after Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” became a surprise best-seller, “After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality,” edited by Heather Boushey, Brad Delong, and Marshall Steinbaum, takes a deeper look at what Piketty’s work means for our current era. The volume, to be released next week, brings together the written reactions of a diverse group of scholars and helps set the research agenda moving forward. We provide an excerpt here.

We all know the role that debt can play in recessions, but what about credit? Nick Bunker writes about research that shows that an increase in an economy’s credit is a better predictor of how severe a recession will be compared to the level of debt.

A recent paper shows that corporations in high-income countries have all increased their savings rate, and are now lending more to the global economy than they are investing in their own corporations.

How has income inequality changed over time? Nick Bunker highlights recent research that looks at data spanning from 1957 to 2013 and finds that the median lifetime income for men has fallen by a stunning 10 percent to 19 percent. And while the results for women are less frightening, the data for the most recent groups show a stagnation.

Links from around the web

Dylan Matthews takes a closer look at the American Health Care Act, and shows why it reverses the reductions in income inequality that Obamacare created and more, leaving many people, especially the poor, worse off than they were before the Affordable Care Act. [vox]

Men’s declining labor force participation isn’t just a short-term economic issue. Andrew L. Yarrow argues that it’s harming today’s kids in a way that may exacerbate the intergenerational transmission of inequality. [san francisco chronicle]

Research shows that noncompete agreements can lower wages, reduce employee motivation, and stymie innovation. This is a sizeable problem considering that 1 in 6 workers are subject to these contracts. Orly Lobel, a University of San Diego Law Professor, argues that we should ban noncompetes, at least for low-wage workers. [new york times]

New research shows that educated workers are much likelier to receive disability insurance benefits compared to workers with a high school degree or less. Kathy Ruffing takes a closer look at why this is considering the outsize benefits of disability insurance for less-educated workers. [cbpp]

Alexia Fernández Campbell wrote about a survey of renowned economists done last week in which every single one rejected the notion that the draft Trump tax plan will pay for itself. [vox]

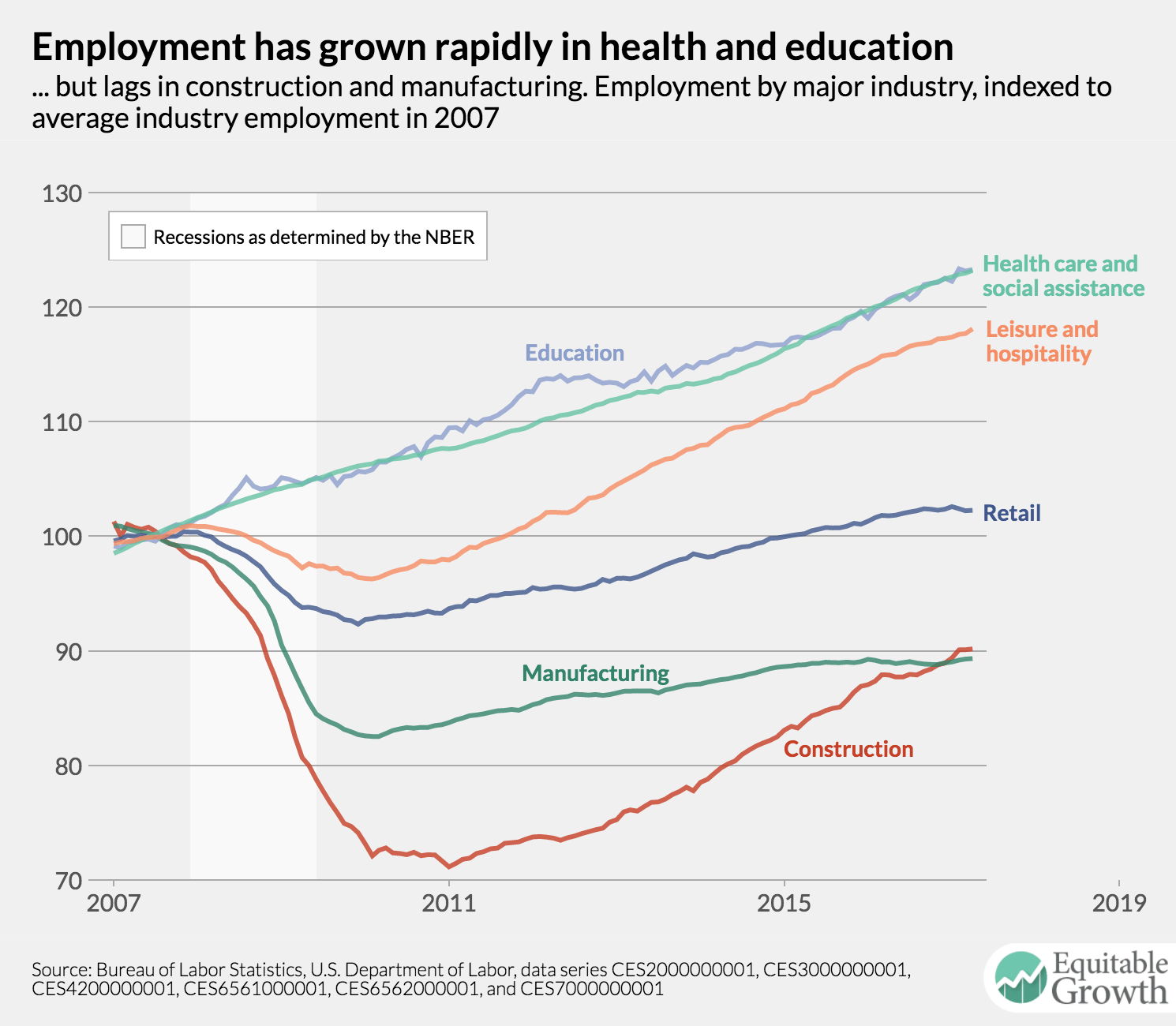

Friday figure

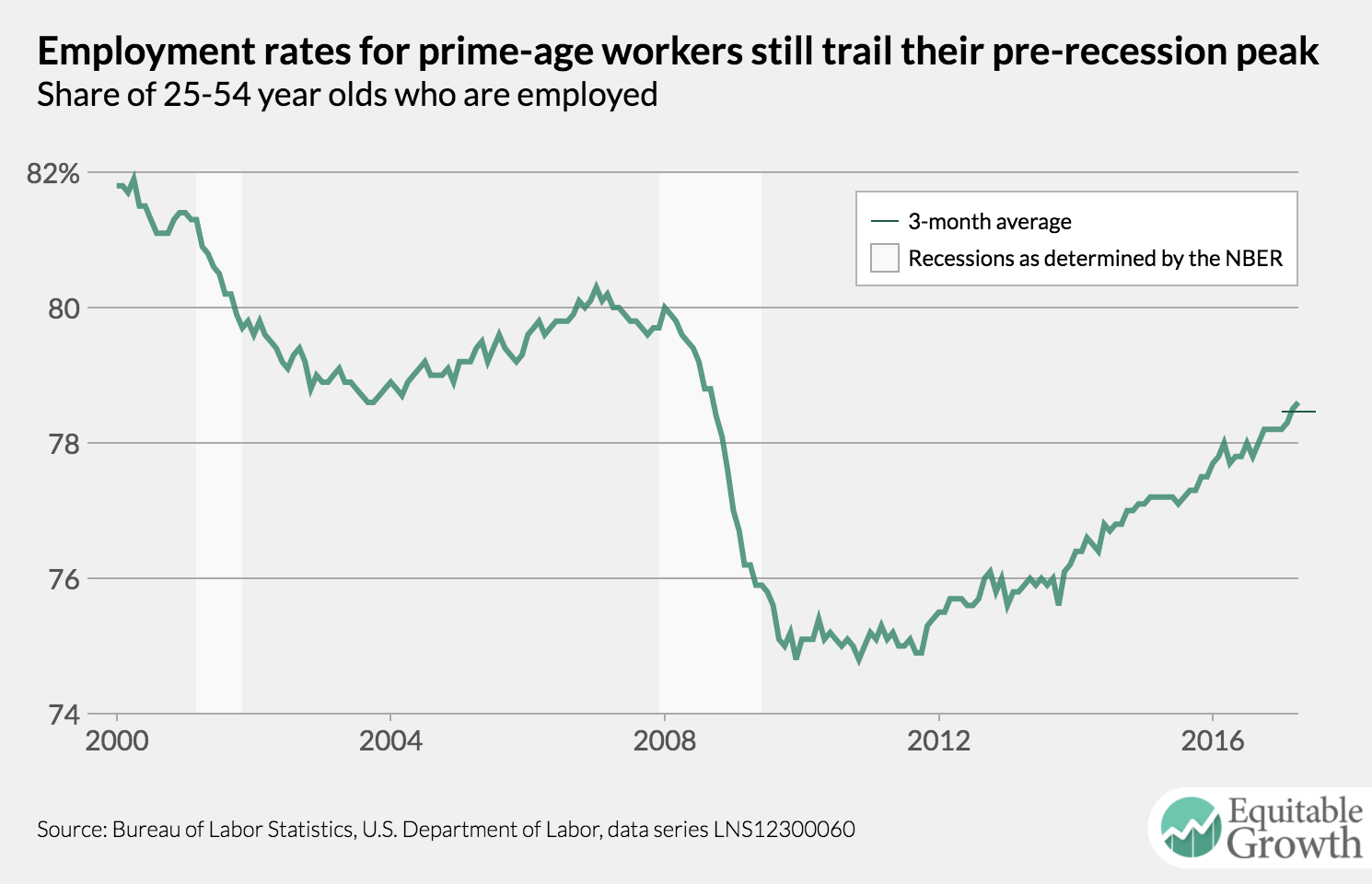

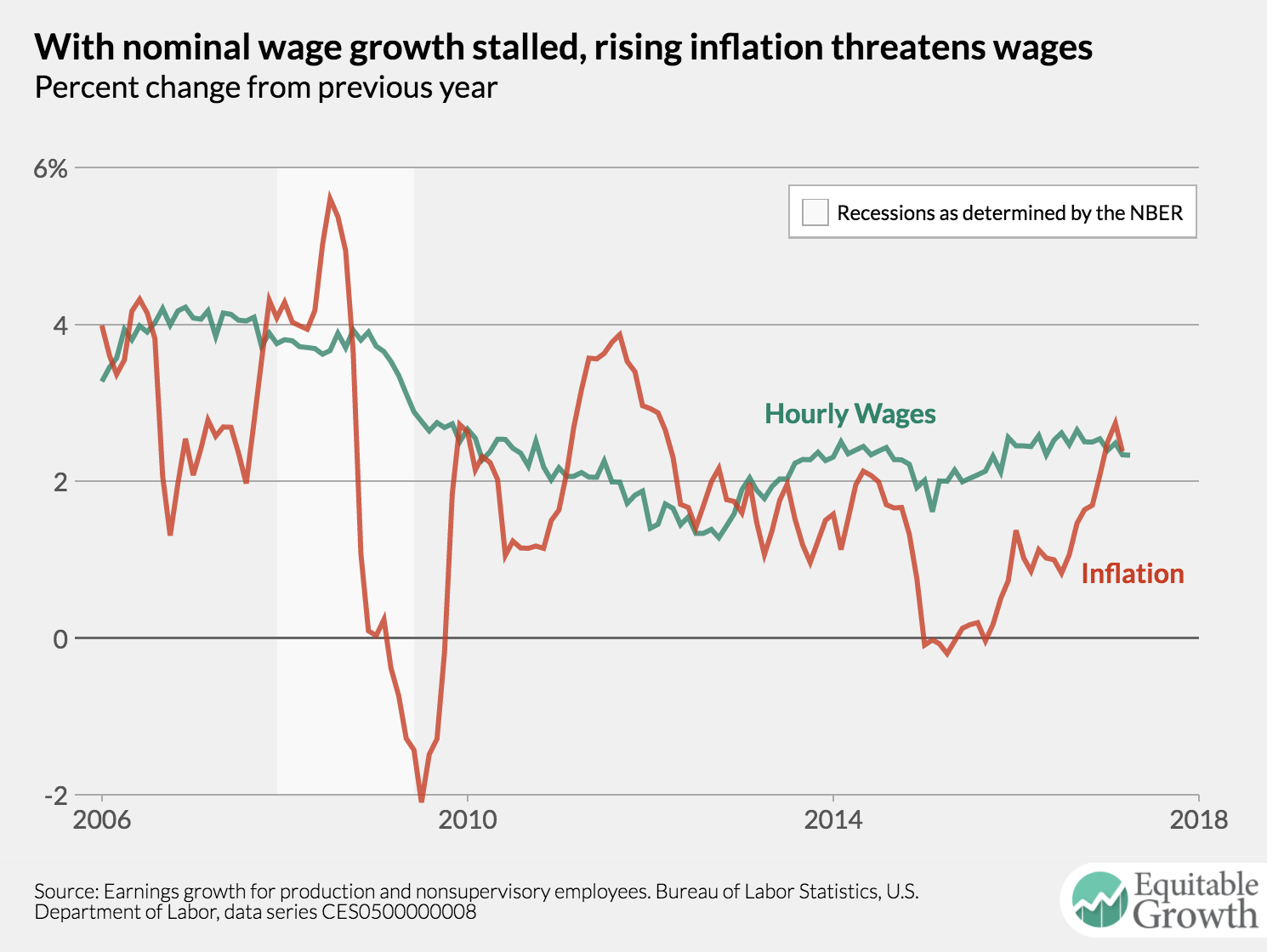

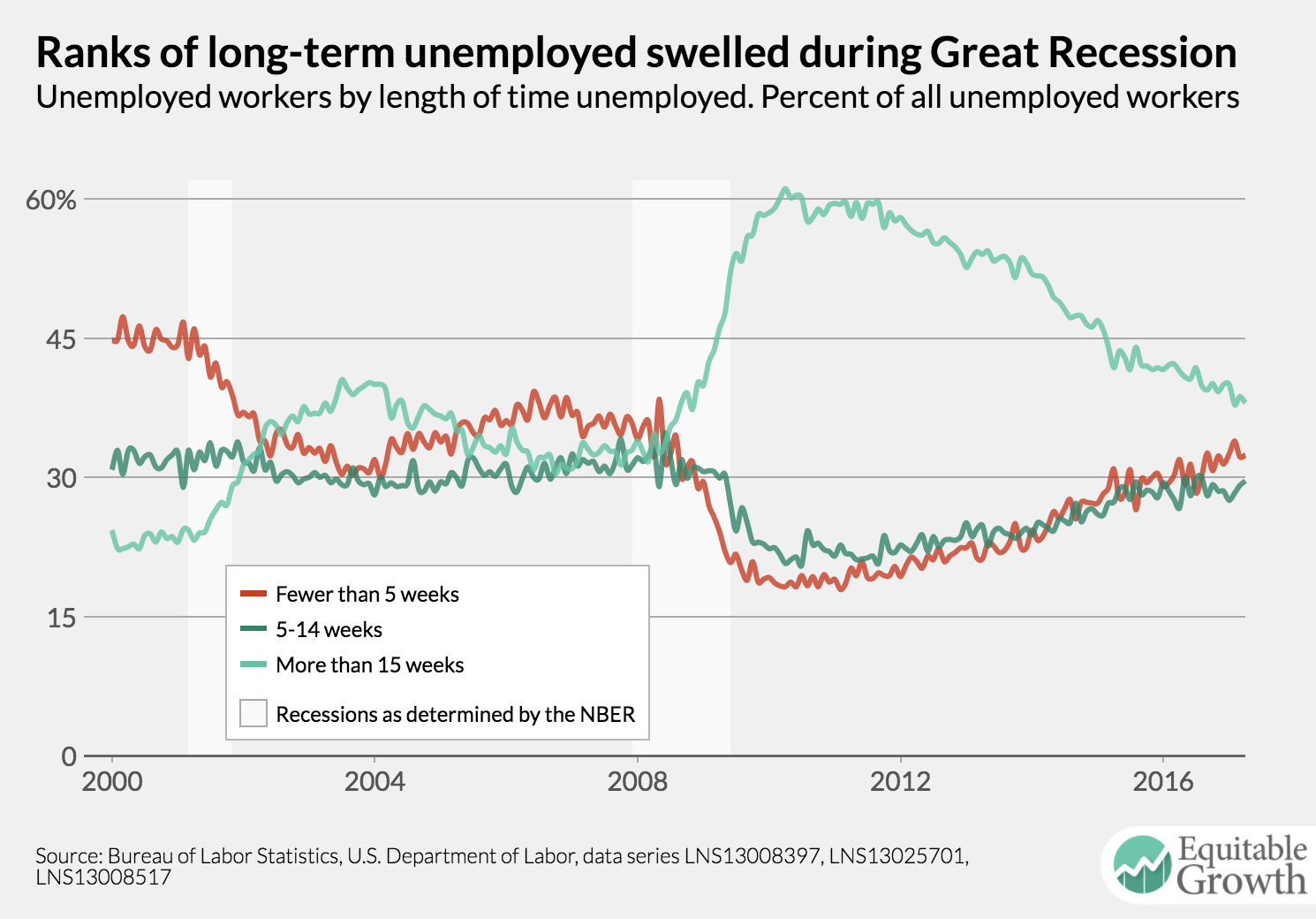

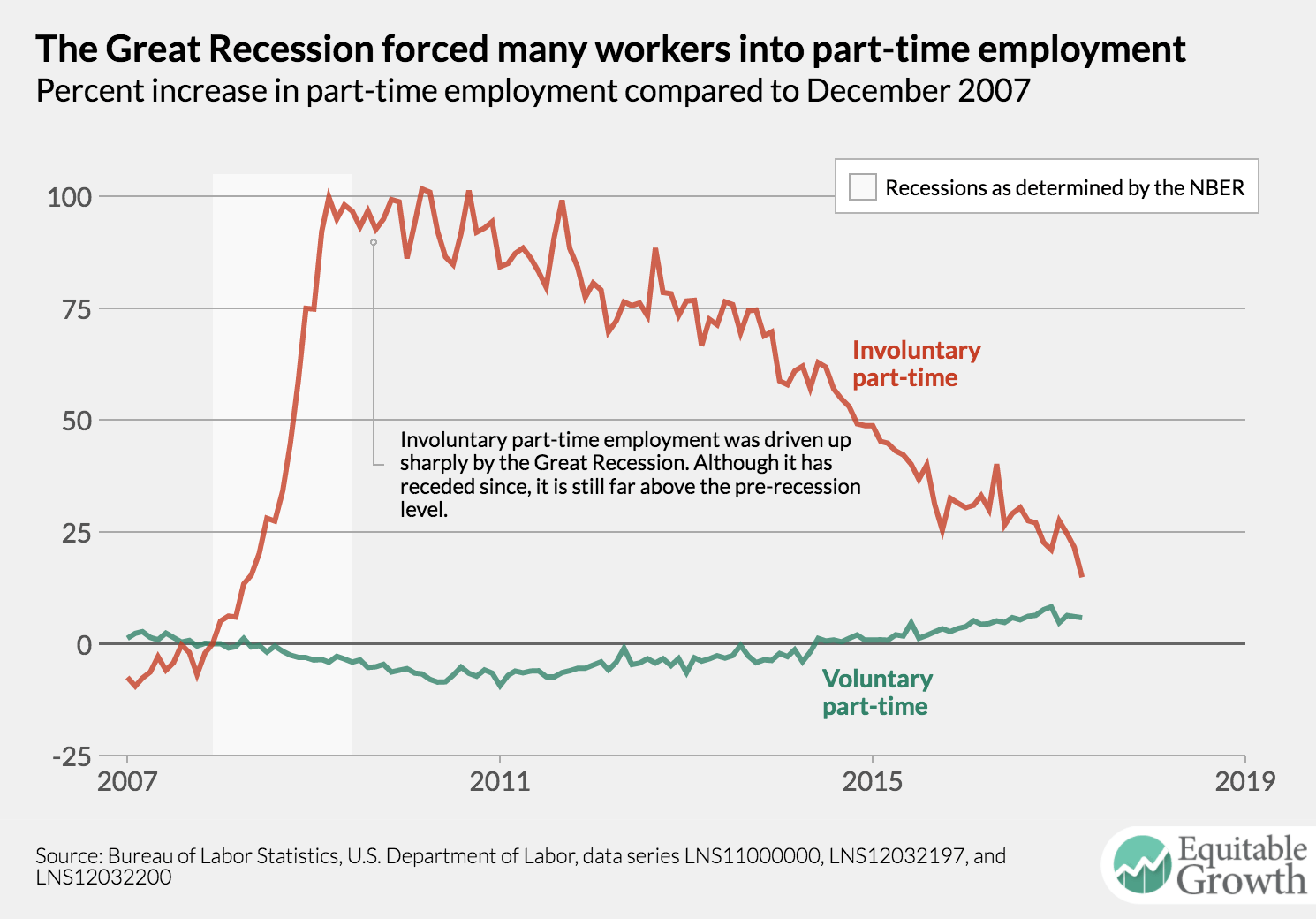

From “Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: April 2017 Report Edition”