Should-Read: Laura Tyson and Susan Lund: Rage Against the Machine?: “Almost every aspect of our economies will be transformed by automation in the coming years…

…But history and economic theory suggest that fears about technological unemployment, a term coined by John Maynard Keynes nearly a century ago, are misplaced…. Marvelous new technologies promise higher productivity, greater efficiency, and more safety, flexibility, and convenience. But they are also stoking fears about their effects on jobs, skills, and wages. Feeding these fears is a recent study by the University of Oxford’s Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, and another by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), which find that large shares of employment in both developing and developed countries could technically be automated….

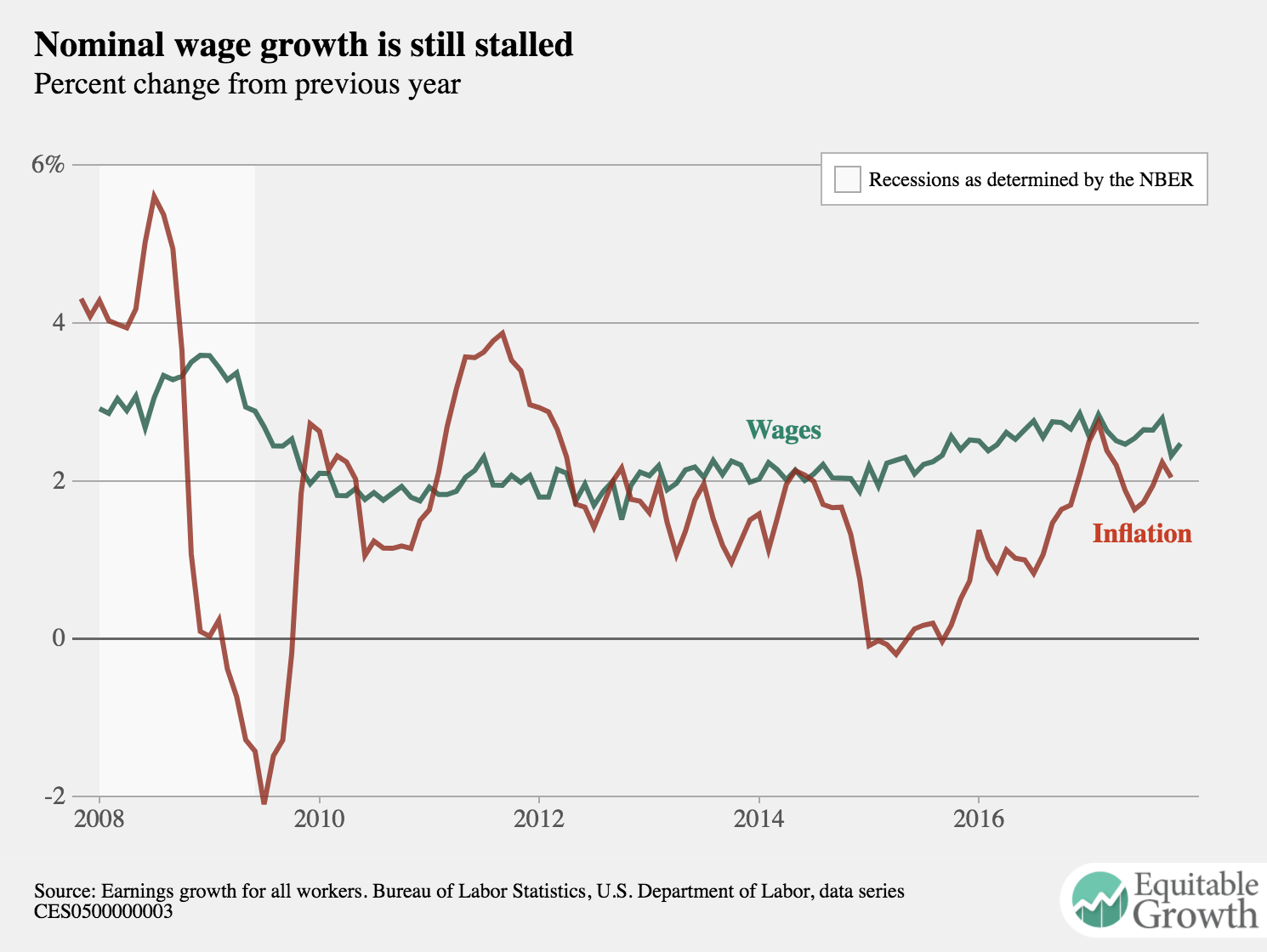

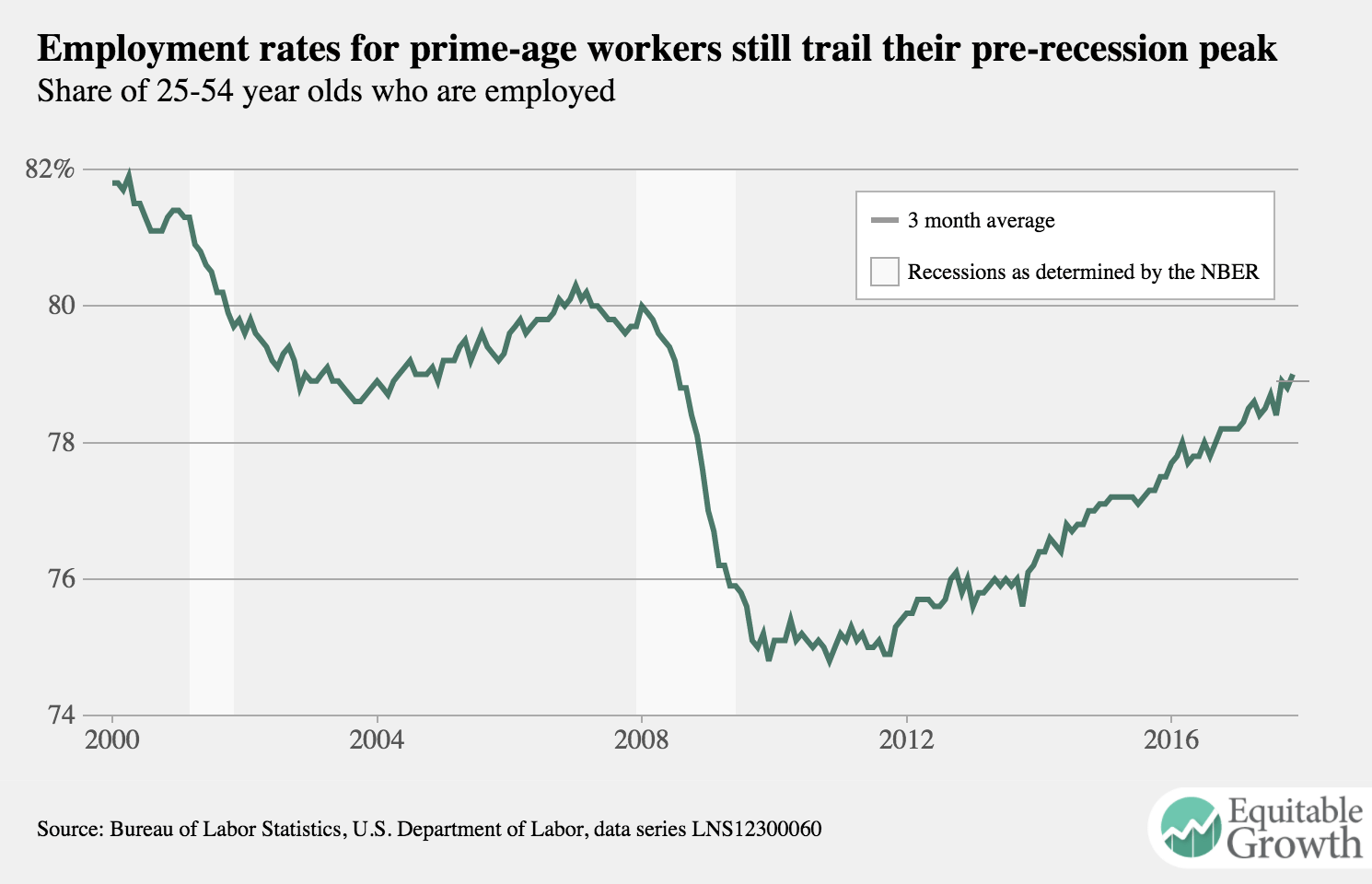

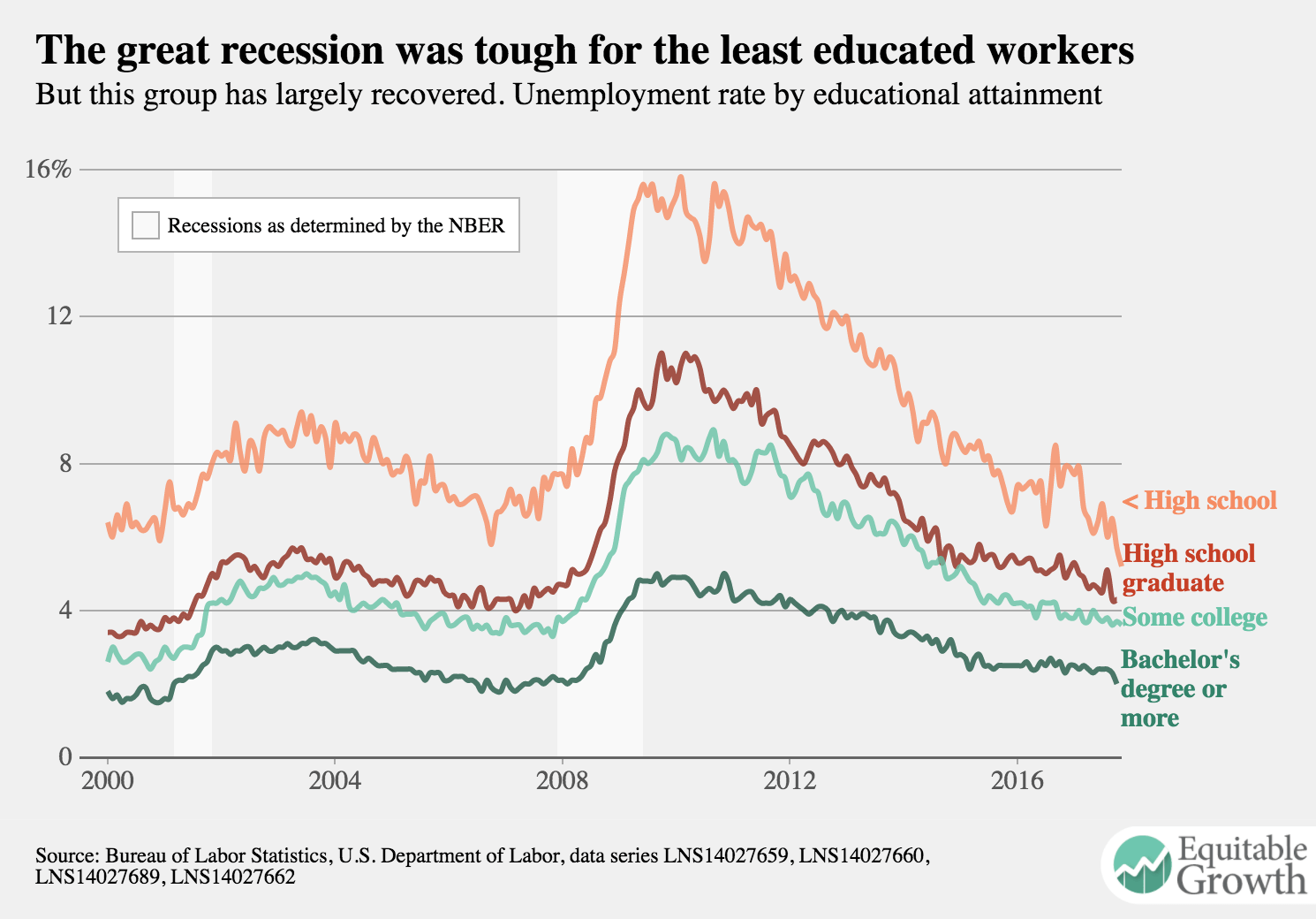

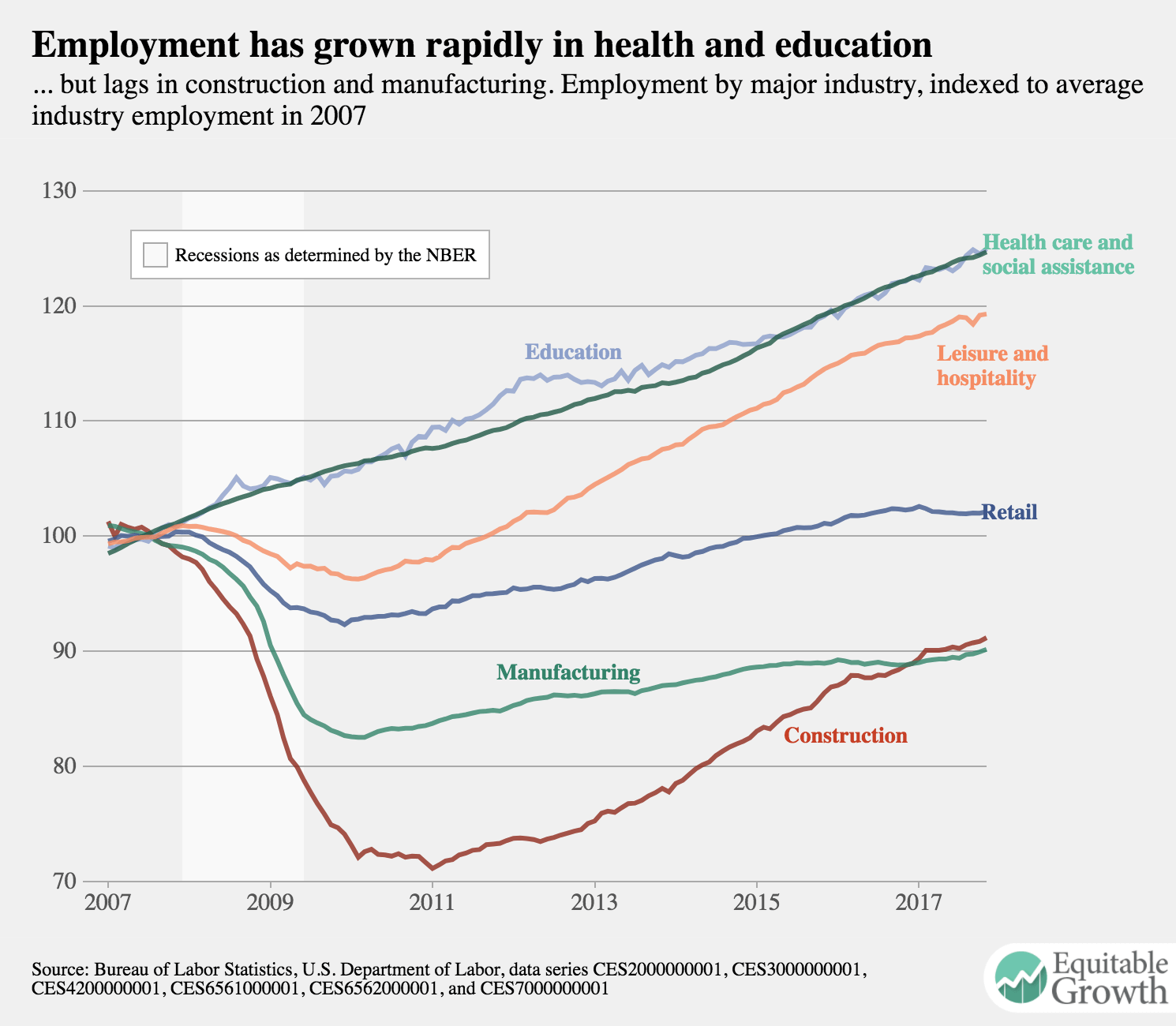

Under a moderate scenario for the speed and breadth of automation, about 15% of the global workforce, or 400 million workers, could be displaced between now and 2030…. The good news is… projected increases in demand… rising incomes, the growing health-care needs of aging populations, and investment in infrastructure, energy efficiency, and renewables…. But the new jobs will differ mightily from the jobs displaced by automation, imposing painful transition costs…. Jobs in major occupational categories like production and office support, and jobs requiring a high school education or less, are likely to decline, while jobs in occupational categories like health and care provision, education, construction, and management, and jobs requiring a college or advanced degree, will increase….

So, what can be done?… Fiscal and monetary policies to sustain full-employment levels of aggregate demand are critical. Policies to promote investment in infrastructure, housing, alternative energy, and care for the young and the aging can boost economic competitiveness and inclusive growth, while creating millions of jobs in occupations likely to be augmented, rather than displaced, by automation. A second response must be a dramatic expansion and redesign of workforce training programs…. Lifelong learning needs to become a reality…. For mid-career workers with children, mortgages, and other financial responsibilities, training that is measured in weeks and months, not in years, will be necessary, as will financial support…. Nanodegrees and stackable credentials are likely to gain in importance. German-style apprenticeships combining classroom work and practical work, and enabling participants to earn a salary while learning, could be important solutions even for middle-aged displaced workers…