This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

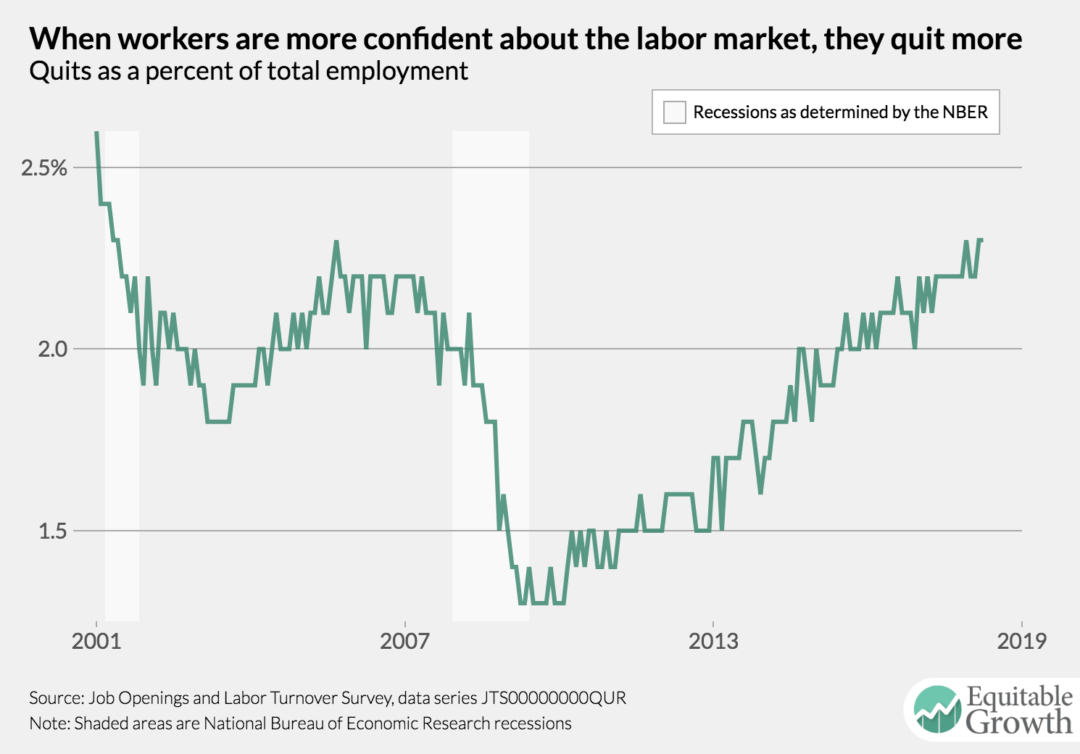

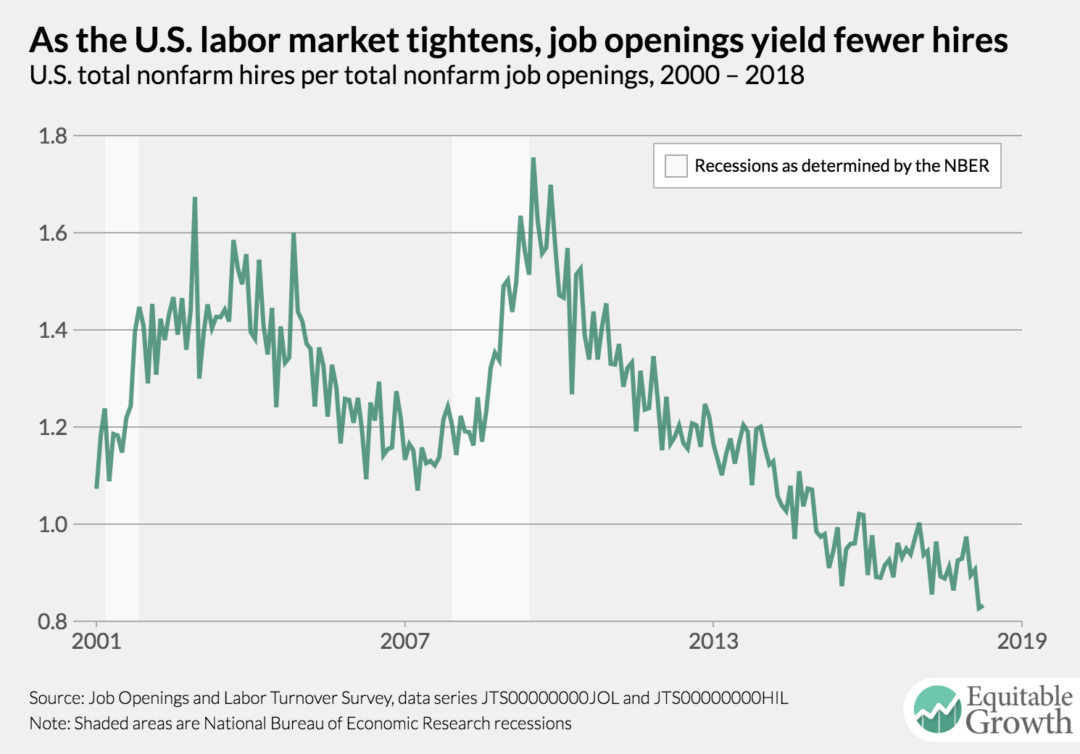

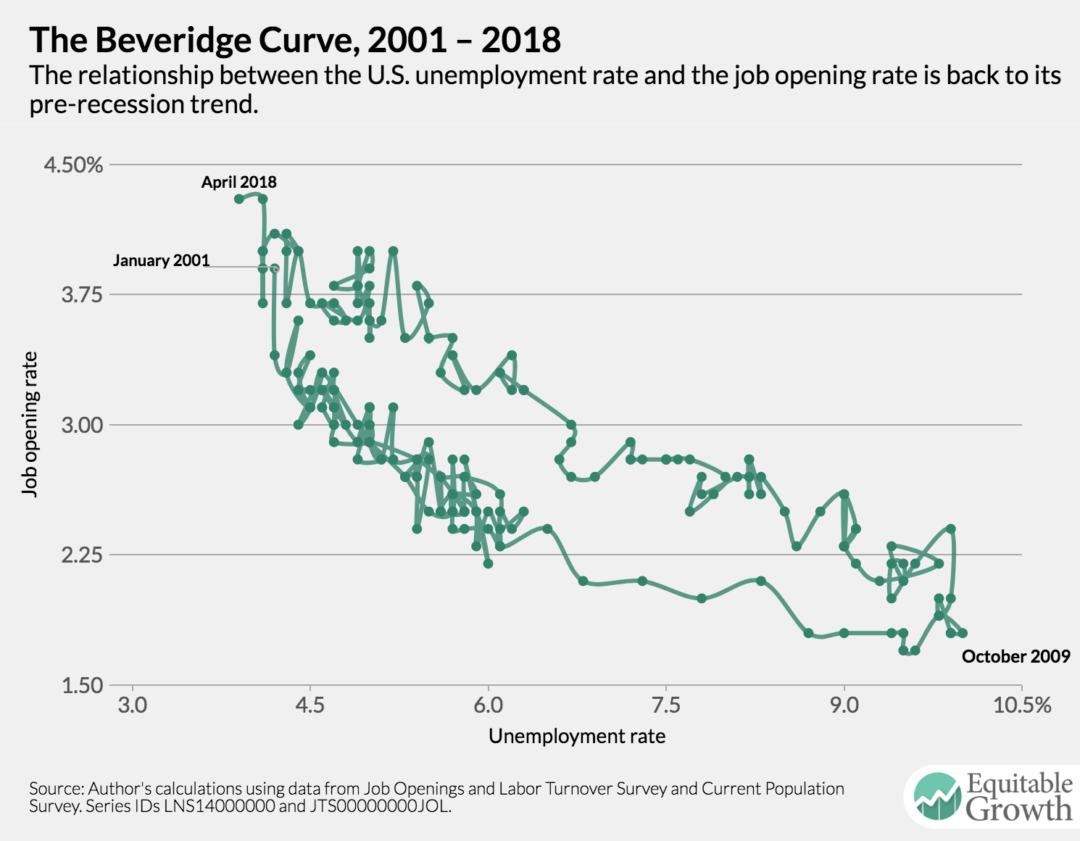

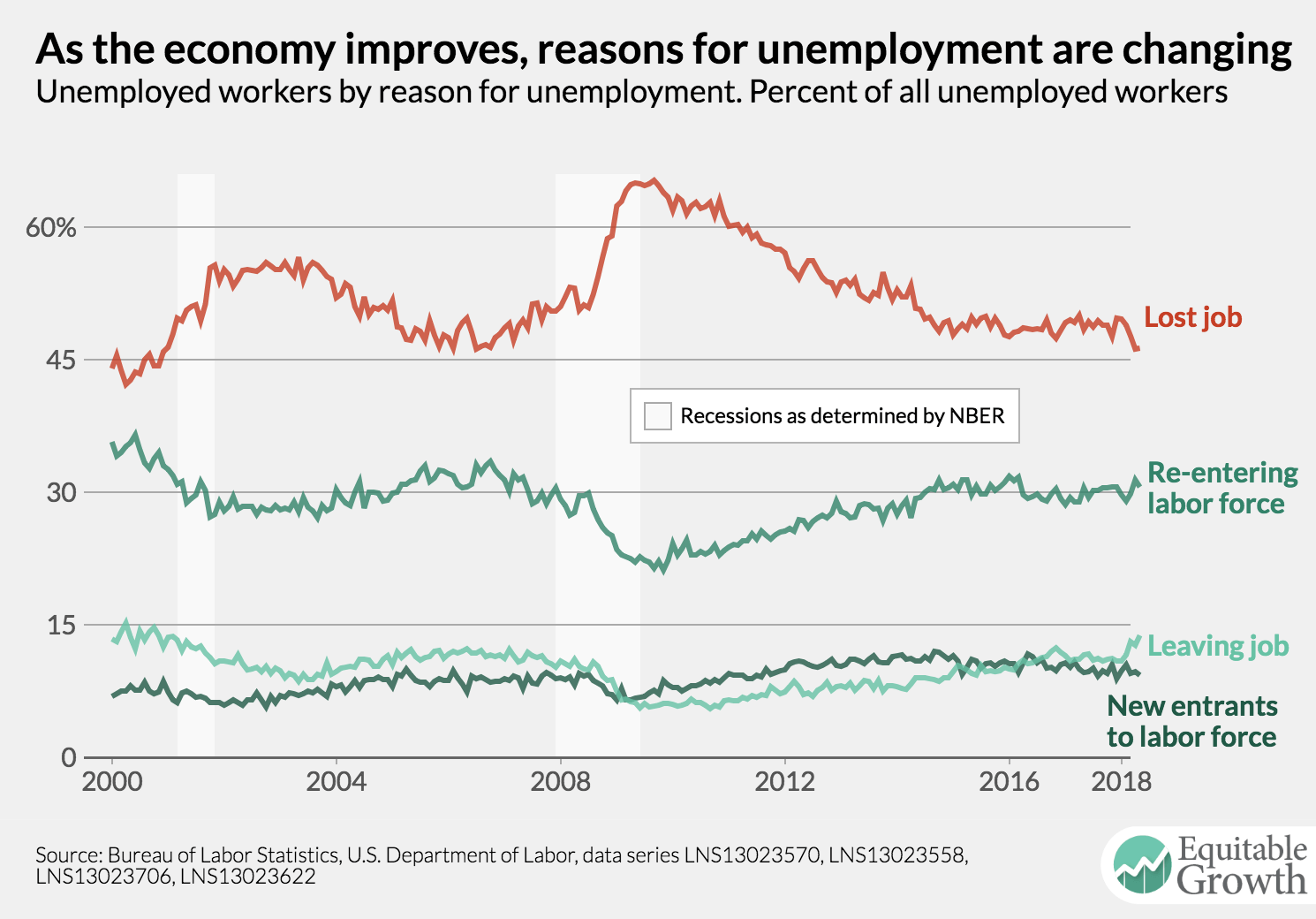

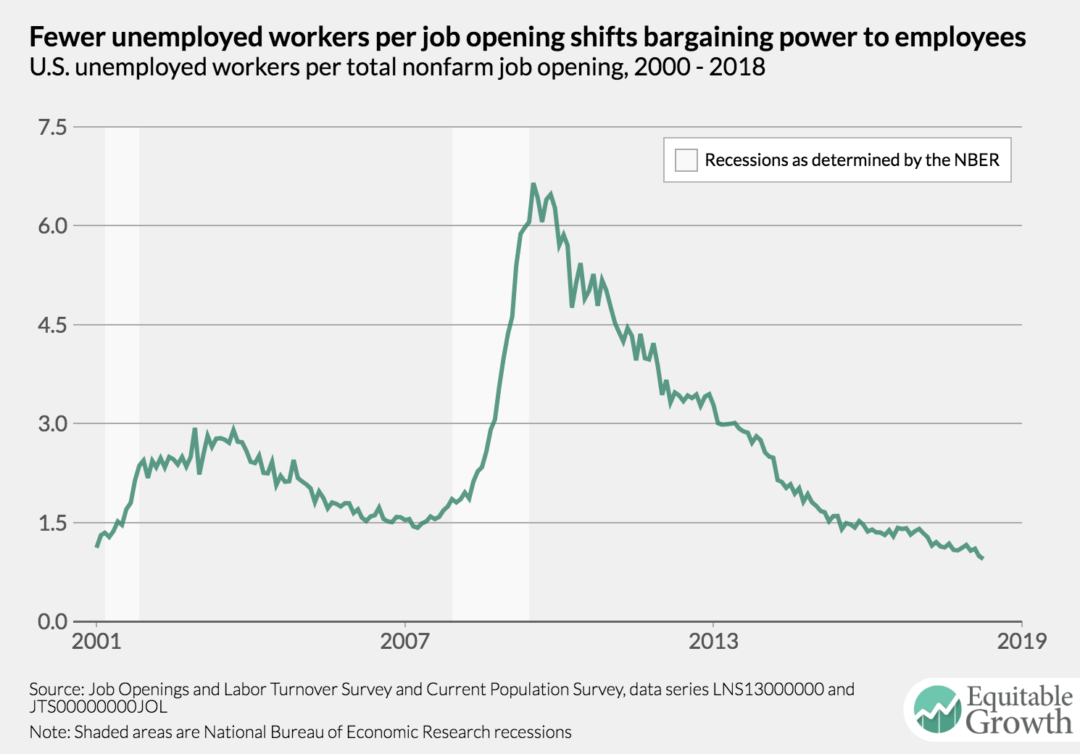

Earlier this week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released the newest data from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey which cover April. Here are four graphs using key data from JOLTS.

How many U.S. workers are in contingent jobs? How many are independent contractors? Kate Bahn set the stage for new data released these week answering just those questions.

John Williams takes the helm of the power Federal Reserve Bank of New York this month. He’s a fan of the Federal Reserve moving to a price-level target when it comes to monetary policy. Would this be a step in the right direction?

Links from around the web

The U.S. labor market hit a level that no one had seen in almost 50 years. Sho Chandra and Jeanna Smialek report on the ratio of unemployment to vacant jobs dropping below 1. [bloomberg]

The federal government this week released new data on contingent work and alternative work arrangements in the United States for the first time in 13 years. Despite the expectations of many that the data would show a big increase in nontraditional work, Ben Casselman writes that “you can see the gig economy everywhere but in the statistics.” [nyt]

Rising income inequality in the United States has manifested itself in many ways. One of the more prominent trends has been the decline of the middle class. Eleanor Kruase and Isabel V. Sawhill list seven reasons to worry about the middle class. [brookings]

Building off previous work, Jason Furman and Peter Orszag try to answer one of the most important questions about the U.S. economy: is slower productivity growth related to higher economic inequality? [piie]

Social scientists are coming to grips with the problem of replication as researchers have difficulty replicating the results of prior research. Anastasia Ershova and Gerald Schneider point out another wrinkle to this problem: updates of statistical software. [lse impact blog]

Friday figure

Figure is from “JOLTS Day Graphs: April 2018 Report Edition”