The state of U.S. wage growth these days is puzzling. The unemployment rate is below where it was before the Great Recession back in 2007, but nominal wage growth is below its level that year and hasn’t picked up in recent years (according to some data series). For economists and analysts who believe that a tighter labor market should lead to higher wages, this disconnect is confusing.

But some analysts, myself included, suggest that the seemingly very tight labor market might not be that tight. The unemployment rate may be low (3.9 percent in April), but the share of workers in their prime years (ages 25 to 54) with a job (79.2 percent) is still below its 2007 level. The prime employment rate can predict wage and compensation growth quite well. Such a continued strong relationship between these variables would suggest that slack remains in the labor market. Stronger wage growth will show up, according to this line of thinking, if the prime employment rate further increases.

Jason Furman, the former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, isn’t sold on this narrative. Furman (now at Harvard University and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute of International Economics and a member of Equitable Growth’s Steering Committee) lays out his concerns in a series of tweets to which Evercore ISI economist Ernie Tedeschi and I have responded. While this might be a quick way to engage on this topic, Paul Krugman has a point that the arguments can be hard to follow. So, let’s lay out some of Furman’s concerns here, as well as some of Krugman’s substantive thoughts, and then turn to a “statement of principles” about this question.

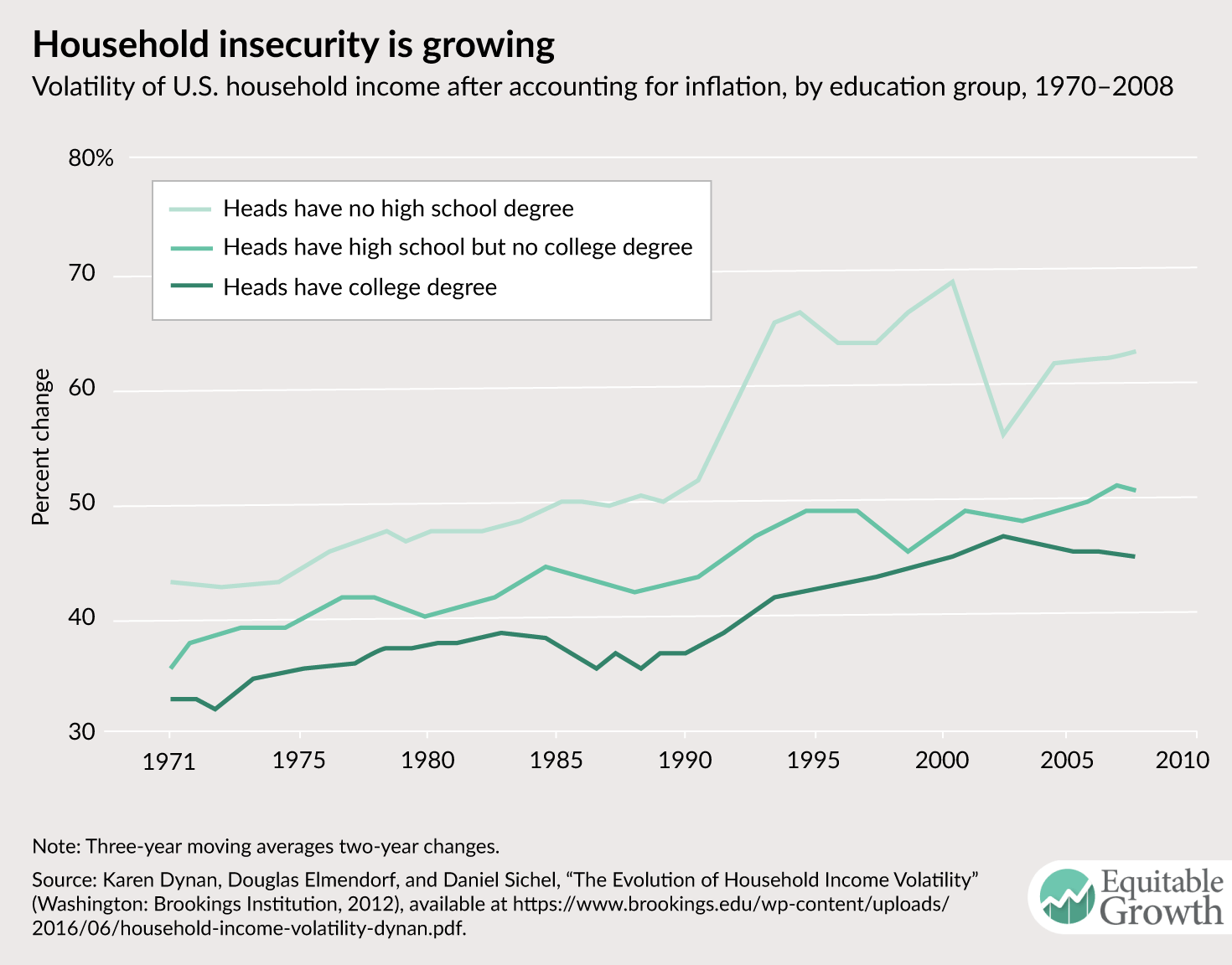

Furman’s critiques of the prime employment rate’s “answer” to the wage growth puzzle can be separated into two parts. The first has to do with the measures of wage growth. Furman notes the differences among the main metrics of wage growth. The commonly cited average hourly earnings, or AHE, data series shows that wage growth is stuck at around 2.5 percent. It hasn’t accelerated much, as the unemployment rate has dropped and the prime employment rate has increased. In contrast, the growth in wages and salaries according to the Employment Cost Index, or ECI, is moving slowly but steadily upward. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The question here is, which wage growth measure do you trust more? The average hourly earnings data are monthly and have a large sample size. But they do not account for the changing composition of workers, which might be biasing measured wage growth downward. The ECI data do adjust for the composition of jobs, but they are only released quarterly and have a smaller sample size. Complicating the picture is the Wage Growth Tracker, a measure of wage growth for consistently employed workers, which was increasing through 2016 but has flat lined in recent years.

Krugman notes in his blog post that increased monopsony power might be responsible for the lack of wage growth. He lays out an argument where firms with market power and which are “scarred” by the memory of the Great Recession are less willing to raise wages. This structural trend could explain why a tight labor market hasn’t led to faster wage growth.

The second part of Furman’s point is that the prime employment rate doesn’t appear to be “stationary.” A stationary variable is a metric that will eventually revert to its trend after a shock. The unemployment rate is a traditionally good example of a stationary variable. It’s at some level prior to a shock (a recession, for example) and then will eventually return to its pre-shock level. Furman’s issue with the prime employment rate is that it might not be stationary. The labor force participation rate of prime-age men has been declining since the late 1960s and women’s participation seems to be on a downward trend as well. This could mean that the level of the prime employment rate is telling economists and policymakers about both cyclical trends (how much slack is left) and secular trends (long-term changes to labor supply or demand in the economy). If the prime employment rate is nonstationary, then it won’t be a good metric for predicting wage growth in the future.

With these critiques in mind, here are some thoughts about what’s holding back wage growth in the United States at the moment. These thoughts are based on two briefs published in recent months looking at the tightness of the labor market and the declining rate at which firms are filling open jobs.

Hiring has not been particularly strong during this recovery in the U.S. labor market, particularly when measured against the number of vacant jobs. Part of the decline in hires per job vacancy—a metric known as the vacancy yield or the job-fill rate—is due to the tightening of the labor market, but even accounting for the low unemployment-to-vacancy ratio hiring is down. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

But only certain kinds of hiring are down. Hiring of workers who were previously unemployed or out of the labor market is in-line with the previous labor market recovery. The hiring that is down is the hiring of already-employed workers.

These two trends could affect wage growth in two ways. One is that the hiring of unemployed and not-in-the-labor-force workers could be affecting the composition of wages and pushing down measured wage growth. These newly hired workers are likely to be earning lower wages, therefore adding them to the pool of employed workers will reduce the average wage overall. Such a trend could explain why the average hourly earnings wage series is still showing muted wage growth.

The Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker tries to account for this issue by only looking at the wage gains of already-employed workers. But again, this measure has been quite weak recently as well. Perhaps the lack of job-switching or hiring of already-employed workers is behind this trend. Wage growth would be stronger according to this metric, perhaps, if more workers were switching jobs. Whether this is a structural or cyclical issue is up for debate. If the issue is cyclical, then the rate of job turnover could increase and push this measure of wage growth up. Or a structural increase in employer market power such as monopsony could be at work, meaning that workers’ movement between firms won’t increase much, and wage growth for already-employed workers won’t increase much, either.

The potential of more workers entering the labor force is at the heart of the debate over the utility of the prime employment rate as a measure of slack. If there’s a significant number of workers who don’t have a job but would like one if they thought one were available, then we would see an increase in the labor force participation rate, all things being equal. In recent months, the labor force participation rate has been fairly constant in the face of an aging population. The participation rate for prime-age workers has been steadily increasing. This shift could explain why the relationship between the unemployment rate and wage growth, as measured by average hourly earnings, isn’t holding up. The workers who are getting hired from this “shadow slack” may have lower wages and therefore be pushing down measured wage growth.

Given the shifting composition of workers in the labor market, looking at a measure of wage growth that accounts for compositional changes makes sense. But we also want a measure of wage growth that captures all employed workers, not just those who’ve been employed for some time. The Employment Cost Index may have flaws, but it’s the best metric of the currently available data for this question. Change in measures such as the Wage Growth Tracker may indicate, for example, that the U.S. labor market has tightened enough to boost job-switching and employers’ poaching of workers.

But what’s happening in the labor market as a whole? It’s not clear that the prime employment rate is fully stationary. There’s some suggestive evidence that this may be true, but more research and thinking on this issue is needed. Analysis of the data shows a weak relationship between the unemployment rate and a good measure of wage growth. The prime employment rate has a much stronger relationship and has done a good job predicting wage growth out of the sample it draws from. The relationship is holding up in practice. Economists and analysts may just need to figure out how it works in theory.