Overview

The U.S. economy seems quite healthy these days. Overall economic growth, as measured by the Gross Domestic Product, has been growing at close to a 3 percent inflation-adjusted pace over the past year. Inflation is moving up toward the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. Long-term interest rates are increasing as well. These signs of progress, however, should not be cause for complacency. The economy may be on an even footing now, but the next recession could be difficult to fight. Policymakers need to contemplate how they will fight the next downturn in an era of secular stagnation.

Download File

What are the macroeconomic policy tools to counter secular stagnation in the United States?

The economic growth of the past several years has happened as inflation-adjusted short-term interest rates were negative and, over the past year or so, fiscal policy stimulated growth with a rising federal budget deficit. Despite this stimulus, inflation is only just now approaching the Fed’s inflation target after almost six years of undershooting while inflation-adjusted GDP growth has been regarded as lackluster. More than four-and-a-half years after former Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers revived the idea, the possibility of secular stagnation still looms over the U.S. economy.

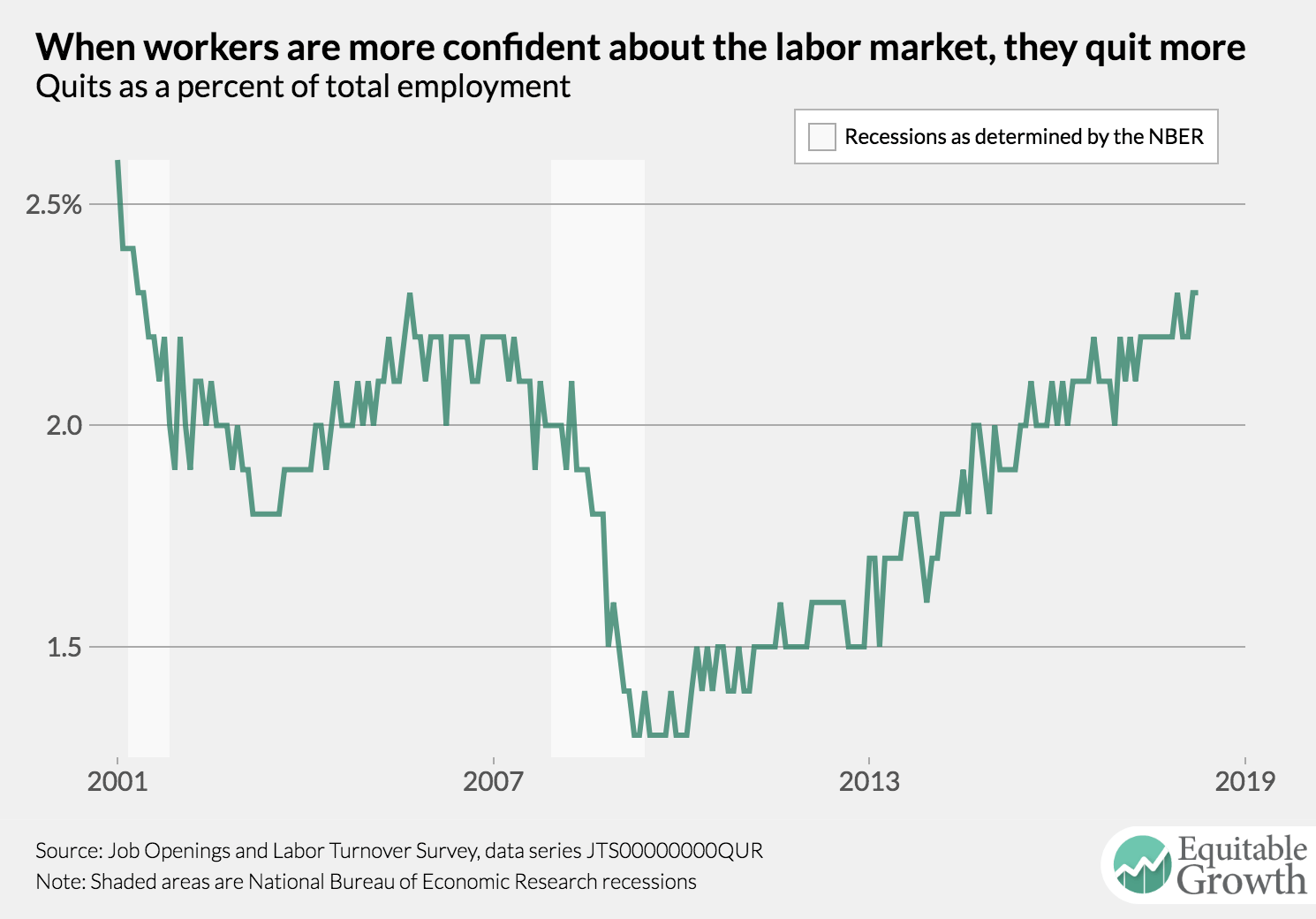

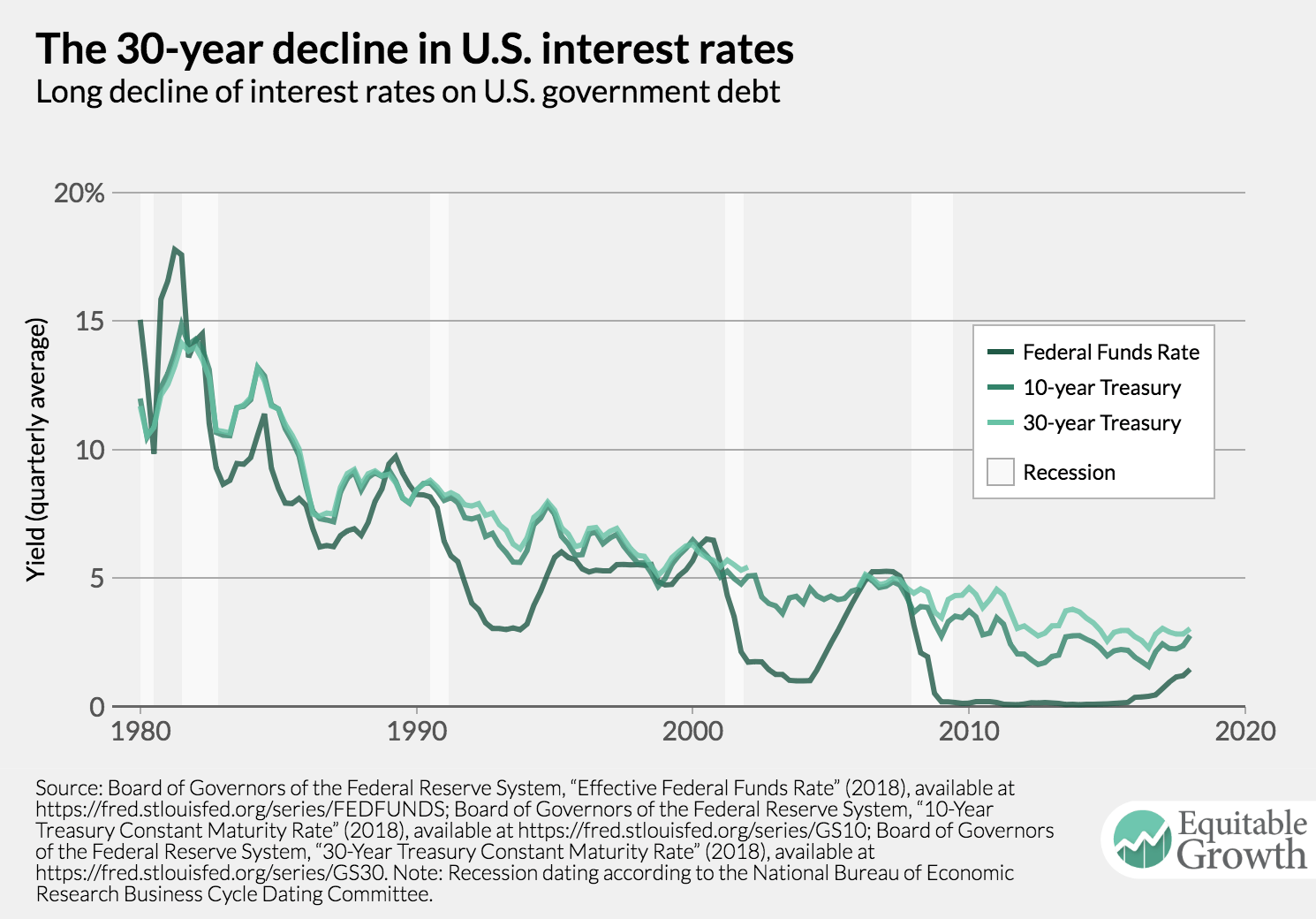

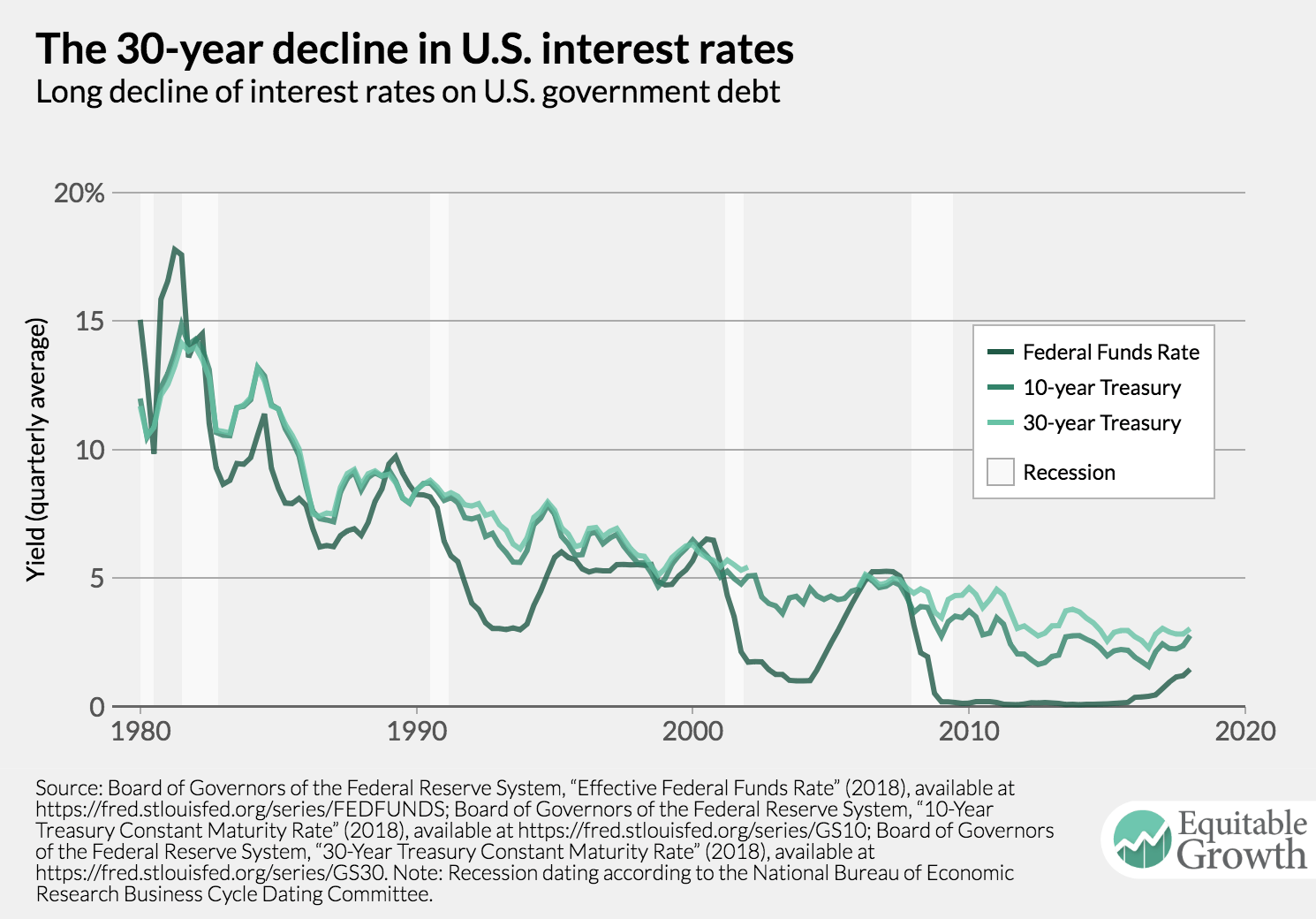

Secular stagnation is a term for the macroeconomic consequences of an economy with a long-term excess supply of desired savings over desired investment. Since the 1970s, savers around the world and in the United States have increased the amount they wanted to save, increasing the supply of loanable funds. The market for savings and investment tries to find an equilibrium, as demand for savings has declined as well. The result has been declining interest rates. Robust growth will be difficult under these situations unless monetary and fiscal policy boost demand sufficiently or rising asset markets unsustainably increase private demand through credit and financial bubbles. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Traditional macroeconomic policy, particularly monetary policy, can deal with such a trend as policymakers can still push short-term rates to the equilibrium level. Eventually, however, the nominal interest rate hits its zero lower bound, and monetary policy becomes constrained. Grappling with this macroeconomic condition is vital for setting the conditions for strong, stable, and sustainable economic growth.

Several macroeconomists have turned their attention to the question of secular stagnation, its causes, and potential policy responses. A review of some of this research shows that taking secular stagnation seriously requires rearranging the macroeconomic policy toolbox. Fiscal policy becomes more important for stabilizing the economy, and monetary policymakers need to rethink which tools will be most useful in this macroeconomic era where they may have diminished power. Much more research is needed into this phenomenon, but the early research demonstrates that policymakers will have to be bold in an era of secular stagnation.

Modeling secular stagnation

The prospect of secular stagnation presents some issues for standard macroeconomic models—namely that secular stagnation cannot exist in them. In the models that influence the academic consensus of macroeconomic policy and the thinking of central bankers, the natural rate of interest can’t be below zero for long. Given that the premise of secular stagnation is that the natural rate of interest can be zero for quite some time, these models aren’t very helpful.

Many of the standard models assume that the interest rate is determined by how much a representative, average consumer discounts money in the future. Firstly, this sets aside the substantial amount of heterogeneity and inequality in the economy that recent research has found crucial for understanding macroeconomic policy. Secondly, this assumes that declines in the interest rates are only temporary. Models will assume that this “representative agent” becomes more impatient about the future, causing a temporary decline in the interest rate that eventually reverts.

Some new research has built models that allow for declining interest rates and extended periods of negative inflation-adjusted interest rates. Brown University economists Gauti Eggertsson, Neil Mehrotra, and Jacob Robbins have developed a model that not only includes these important interest rate features, but also allows for a broader set of factors to determine interest rates. Put simply, their model has the market for assets—set by the supply of and demand for savings—to be the source of interest rates.

Eggertsson, Mehrotra, and Robbins had to perform, as one of the co-authors put it, “open-heart surgery” on the standard models to answer questions about secular stagnation. Whereas in more standard models, the representative agent can look infinitely into the future, the agents in their models won’t live forever, and there are younger generations with which they can trade assets.

It’s this market for savings that allows for more interesting changes in interest rates. Shifts in the supply of desired savings or the demand for these savings determine the interest rate. A shift out in supply of savings, all things equal, will push down interest rates, while an increase in demand for savings, all things equal, will increase the interest rate. An increase in life expectancy, for example, will increase the supply of savings as workers have to save more for retirement. Assuming no other changes, this would push down the natural rate of interest.

These trends can also be thought of as changes in supply and demand for assets. In this case, the demand for assets is a way of presenting the same forces that drive the supply of desired savings. Think again about an increase in life expectancy. Workers needing to save more will need to put their money in assets to fund their retirements. Longer retirements would then increase the demand for assets. And since the price of a bond is inversely correlated with the interest rate, interest rates will go down as prices go up. While this is the framework that some papers use, this issue brief will examine shifts in the supply of and demand for savings.

Another way to think about this increase in the supply of savings is a decrease in the economy’s aggregate demand, or the total amount of demand in the economy. Increased demand for assets means that money that would have increased demand for current goods is now being saved to purchase goods and services at a later date. This is similar to how recessions, or temporary declines in aggregate demand, happen in Keynesian models. Something causes households or businesses to pull back on consumption and increase their savings, which leads to a decline in output. But in the long-run case, the market for supply moves to a new equilibrium with a lower interest rate.

Other models looking at the decline in the natural rate of interest use the market for savings or assets as the key to understanding movements in the interest rate. Economists Adrien Auclert at Stanford University and Matthew Rognlie at Northwestern University look at how the increase in income inequality in the United States may have increased savings as high-income households increase their precautionary savings to protect themselves from income volatility. Similarly, Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Ludwig Straub finds the increased savings of rich households had an important role in declining interest rates, though the reason for the increase differs from Auclert and Rognlie’s reason.

Implications for fiscal policy

These modeling changes might be interesting in and of themselves, but what do they imply for policymakers? The implications for fiscal policy are greatest. In short, fiscal policy appears to be a much stronger stabilization tool than previously thought.

The dominant view of fiscal policy before the Great Recession of 2007–2009 was that it was an inefficient form of stimulus and that the stabilization of the macroeconomy should be left to central banks and monetary policy. This understanding is a product of the Great Moderation, the period of relative macroeconomic stability starting in the late 1980s and ending with the Great Recession. Many economists believed that more effective macroeconomic management, mainly via monetary policy, was responsible for a good part of the moderation.

But the events of the Great Recession and research work since then highlights the important role of fiscal policy in stimulating the economy in the current environment. Jason Furman, during his time as the chair of the Council of Economic Advisers in the Obama administration, presented this new view of fiscal policy and the attendant policy implications. Research on the fiscal multiplier—a measure of how much economic activity a dollar of fiscal stimulus creates—has found that stimulus in the United States during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 was quite effective.

Yet the models of secular stagnation find fiscal policy to be an effective tool against secular stagnation in a different way. Remember that secular stagnation and declining interest rates are due to changes in the supply and demand for savings. In these papers, stimuative fiscal policy (rising budget deficits) leads to increases in interest rates that counteract secular stagnation by increasing the demand for savings and loans. Government debt, in these models, soaks up the excess savings in the economy. The government would act as a sort of “borrower of last resort,” a parallel to a central bank’s role as a “lender of last resort.”

What should the government do with the funds it borrows? According to the Eggertsson, Mehrotra, and Robbins model, it doesn’t seem to matter much: “The increase in government debt could be directed to the young, toward government spending, or distributed to the middle aged and the old in accordance with the fiscal rule.” Auclert and Rognlie’s model finds that fiscal policy counteracts the negative impacts of recessions, the increasing inequality during recessions, so this suggests that polices that insure against falls of income for those who lose their job during recessions—unemployment insurance, for example—may be helpful.

But the while the distribution of the funds might not be important, the source of the funding is key for understanding the impact of fiscal policy. The highest multipliers are found when the increase in spending or reduction in taxes are funded entirely by debt. Remember, the problem of secular stagnation is an excess of savings. Fiscal policy is most effective if it can increase the demand for loans and push up interest rates (the price of loans). Financing an increase in spending with taxes or reducing spending to pay for a tax cut would reduce the amount of excess savings the government is using. In fact, Eggertsson, Mehrotra, and Robbins find that certain tax increases in their model would make the fiscal multiplier negative and actually reduce growth by increasing the amount of savings in the economy.

How should these results inform the thinking of fiscal policymakers? Fiscal policy is an important and powerful tool in a state of secular stagnation. Policymakers should be well aware of the context of fiscal policy and how increased government debt can be a solution. If policymakers are concerned about an economy where low interest rates imperil macroeconomic stabilization or that excessive savings might inflate a financial bubble, then increased government debt would help solve those problems.

Implications for monetary policy

Monetary policy in a state of secular stagnation faces a significant problem. Monetary policymakers try to bring the economy into equilibrium by changing the price of loans and credits via interest rates. Secular stagnation throws a wrench into the monetary policy machine as interest rates have dropped so much that policymakers have less control over them. Models of secular stagnation find that monetary policymakers could make some changes to their toolkit, but their ability to stabilize the economy on their own is still more constrained.

The problem for monetary policy during secular stagnation is the nominal zero lower bound. Interest rates can be thought of as the return on holding onto money. Central banks can make money less valuable to hold onto and make consumers and businesses more likely to spend that money if they lower interest rates. But if interest rates get to zero, central banks can’t (at least at the moment) push rates below zero. A negative nominal interest rate would mean that money in a bank account would decline in nominal (unadjusted for inflation) terms. The dollar figure in your bank account would go down. The thinking has long been that depositors would just with draw their money from bank accounts and hold them in cash, which has a fixed zero percent nominal interest rate. It always has the same value in nominal terms. Banks wouldn’t be able to charge the negative nominal interest rates.

Forward guidance

The current approach is to sidestep the issue of control over current interest and use promises around future interest rates as a policy tool itself. A central bank may promise to keep nominal interest rates at zero until unemployment or inflation hits certain levels. Forward guidance, as this is called, is premised on the assumption that households and businesses will be aware of this commitment and that they believe the central bank will hold firm to the commitment.

The households in the Eggertsson, Mehrotra, and Robbins model are not “infinitely lived” (meaning there are multiple overlapping generations of agents in the model), so commitments about the future are less powerful than in other models. Furthermore, since the state of secular stagnation is permanent and interest rates will be near or at the zero lower bound for quite some time, then households might not believe that monetary policy will have traction anytime soon. In other words, people either don’t believe the central bank’s commitment or they don’t think it’s relevant to them. In the model, then, forward guidance is far less powerful than many models and policymakers believe.

Increasing the inflation target

One popular suggestion for counteracting the zero lower bound is to bypass the nominal bound by increasing the amount of inflation in the economy. Central banks may be bound by a nominal lower bound, but they can make the inflation-adjusted value of money lower by decreasing inflation-adjusted interest rates. With the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent inflation target, the lower bound on inflation-adjusted rates is negative 2 percent. But a higher inflation target—say, 4 percent—would reduce this bound to negative 4 percent (a 0 percent nominal interest rate minus 4 percent inflation).

The models from Auclert and Rognlie and from Eggertsson, Mehrotra, and Robbins both find that a higher inflation rate could be effective, but that central banks must not be timid and have to set the inflation target high enough. A shift to a 4 percent inflation target might not be large enough if the natural rate of interest has fallen below negative 4 percent. A higher inflation target would be able to solve many instances of secular stagnation, but there would be a chance that the central bank hasn’t gone far enough. Raising the inflation target could be a useful tool for fighting against secular stagnation, but it’s not powerful enough to fully solve the problem.

Negative nominal interest rates

What about getting rid of the nominal lower bound or at least significantly lowering it? While economists and central bankers had long regarded the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates as a solid border, it appears to be a bit porous. The European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan have both managed to set short-term nominal interest rates below zero. How is this possible? People were supposed to take their money out of bank accounts and convert it to cash if the possibility of negative nominal rates was raised. But it appears that money in a bank account and cash in a wallet (or under a mattress) are not perfect substitutes. The benefit of the convenience of having money in a bank account may outweigh the cost of seeing a nominal decline in the value of the account. Just how negative nominal interest rates can get is likely a function of demand for cash in an economy.

Now that policymakers know it’s possible, the question is whether setting nominal interest rates below zero is an effective policy. In the Auclert and Rognlie model, moving the effective lower bound below zero has a sizeable effect. According to one exercise using their model, pushing the nominal lower bound a bit below negative 0.4 percent allows the U.S. economy to get back to a state of full employment. The Eggertsson, Mehrotra, and Robbins paper doesn’t allow for negative nominal interest rates, so it cannot look at the impact of negative rates. Other research by Eggertsson, however, takes a dim view of the expansionary effects of negative nominal rates. Better understanding the mechanics of negative nominal interest rates and how they function in secular stagnation seems to be a ripe area for policy-oriented macroeconomists to investigate—a trend that has started and hopefully will continue.

Conclusion

If secular stagnation is an enduring feature of the U.S. economy and new models of it are broadly correct, then the macroeconomic policy toolkit needs to change. Ignoring it could mean the recovery from the next recession will be weak and result in a material declining in living standards for millions of Americans through higher unemployment and lower wages.

The long-term decline in interest rates and excess savings means fiscal policy can no longer be thought of as a secondary concern. Increased federal budget deficits and higher federal debt in a state of secular stagnation are positives, as they will increase short-term growth and push interest rates up. How much U.S. government debt the market could handle isn’t known, but the lower interest rates of recent years and the experience of Japan—with its current debt-to-GDP ratio of about 250 percent and negative inflation-adjusted long-term rates—suggest that demand for high-quality government debt is quite high.

The power of monetary policy is diminished under secular stagnation, but monetary policymakers don’t appear to be impotent. Forward guidance may not have the power that the current consensus believes it does, but changes to inflation targets and pushing nominal interest rates below zero may hold some promise. Whether monetary policy could be further strengthened by changing the current regime of inflation targeting to a price-level target or a nominal GDP level target is an interesting possibility. The current debate among members of the Federal Open Market Committee will hopefully consider these questions moving forward.

Of course, more research and thinking about these questions are needed. The papers reviewed in this brief are part of the beginning of what will hopefully become a large literature. Policymakers may well need all the help they can get in the years to come.

Further reading

Want to read more about the issues and research discussed in this brief? Below is a list of research papers, policy briefs, blog posts, and other pieces that flesh out some of these ideas, present other models and concepts, and evaluate other policy options.

Heather Boushey and Lawrence H. Summers, “Equitable Growth in Conversation: An interview with Lawrence H. Summers,” February 11, 2016, http://equitablegrowth.org/research-analysis/equitable-growth-in-conversation-an-interview-with-lawrence-summers/.

Emi Nakamura and others, “The Elusive Costs of Inflation: Price Dispersion during the U.S. Great Inflation.” Working Paper (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016), available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w22505.

Janet Yellen, “Macroeconomic Research After the Crisis,” speech given at “The Elusive ‘Great’ Recovery: Causes and Implications for Future Business Cycle Dynamics” 60th annual economic conference (Boston, MA: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, October 14, 2016), available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20161014a.htm.

Dan Davies, “How Secular Stagnation Came to Smurf Village,” The Long and Short blog, March 20, 2015, available at https://thelongandshort.org/growth/secular-stagnation-explained.

Josh Bivens, “In Debate Over ”Secular Stagnation,” Don’t Let Legitimate Concerns Over Inequality Let Austerity Off the Hook,” Economic Policy Institute blog, November 22, 2013, available at https://www.epi.org/blog/debate-secular-stagnation-dont-legitimate/.

Paul Krugman, “It’s Baaack! Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (2) (1998): 137–205.

Gauti B. Eggertsson, Neil R. Mehrotra, and Lawrence H. Summers, “Secular Stagnation in the Open Economy,” American Economic Review 106 (5) (2016): 503–7, available at https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20161106.

Joseph E. Gagnon, “The Fed Buys into Secular Stagnation,” Realtime Economic Issues Watch blog, September 20, 2017, available at https://piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/fed-buys-secular-stagnation.

Lael Brainard, “Normalizing Monetary Policy When Neutral Interest Rate Is Low,” speech given at Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (Stanford, CA: Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, December 1, 2015), available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20151201a.pdf.

John C. Williams, “Monetary Policy in a Low R-Star World” (San Francisco, CA: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2016), available at https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2016/august/monetary-policy-and-low-r-star-natural-rate-of-interest/.

Nick Bunker, “How income inequality may affect U.S. interest rates,” Value Added blog, February 19, 2018, available at http://equitablegrowth.org/equitablog/value-added/how-income-inequality-may-affect-u-s-interest-rates/.

Nick Bunker, “Cash [demand] rules everything around us,” Equitable Growth blog, February 1, 2016, available at http://equitablegrowth.org/equitablog/cash-demand-rules-everything-around-us/.

Nick Bunker, “Modeling the decline in U.S. interest rates,” Equitable Growth blog, February 14, 2017, available at http://equitablegrowth.org/equitablog/modeling-the-decline-in-u-s-interest-rates/.