New research shows unstable schedules do not offer more flexibility for U.S. workers

A growing body of research documents the costs of schedule instability for workers in the United States. Inconsistent shifts make it harder for workers to maintain routines or plan their lives outside of work. For workers paid by the hour, unstable schedules can mean unreliable earnings and financial hardship. The work-life conflict and economic insecurity associated with unstable schedules take a toll on the health and well-being of workers and their children.

Unstable scheduling is often framed as a problem for particular groups of workers who are more vulnerable to employer exploitation, whether because of a greater need for schedule accommodations, a lack of better job options, or any number of other possible factors. But this framing misses the broader extent and economic significance of the problem.

In prior research with Susan Lambert at the University of Chicago, I show that unpredictable and unstable schedules are widespread in the United States, affecting between 10 percent to 30 percent of civilian employees. While schedule instability is more prevalent among part-time workers, Black workers, and workers under the age of 35, it still affects a substantial share of full-time, White, and middle-aged workers. Unpredictable schedules also are common not only in low-wage service industries, such as hospitality and retail, but also across higher-wage construction, production, and transportation jobs.

Why do so many U.S. workers put up with unstable schedules? In a recent working paper, I shed light on this issue by answering a related question: What, if anything, do workers gain from these arrangements? I reframe schedule instability as a problem of allocating risk and reward in the employment relationship. In a fair, well-functioning market, those who accept greater risk can expect greater reward. So, I ask, do scheduling risks come with higher pay, flexibility, or other rewards for workers?

To answer these questions, I test three potential explanations for why workers accept unstable schedules. First, I test the claim that workers are compensated for scheduling risk with higher pay or advancement opportunities. Second, I test the claim that workers with unstable schedules benefit from better work-life balances or flexibility. Third, I test the claim that workers bear uncompensated scheduling risk because they have limited access to stable schedules.

The best available data on labor scheduling and compensation come from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 Cohort, or NLSY97 for short. This survey, sponsored by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, collects exceptionally detailed information on schedule arrangements, pay, and benefits for a nationally representative sample of employees born in the early 1980s. These workers were in their 20s and 30s during the period I studied, from 2011 to 2018.

For this period, the NLSY97 is the only national survey to include questions about the range of weekly hours, length of advance notice, and degree of control the worker or employer has over scheduling. The NLSY97 collects data every other year, providing repeated observations of workers as they move through different jobs and schedule arrangements. These data allow me to identify multiple types of scheduling risks—defined by different combinations of volatile hours, short notice, and little or no worker control—and to analyze the marginal effects of scheduling risk on compensation.

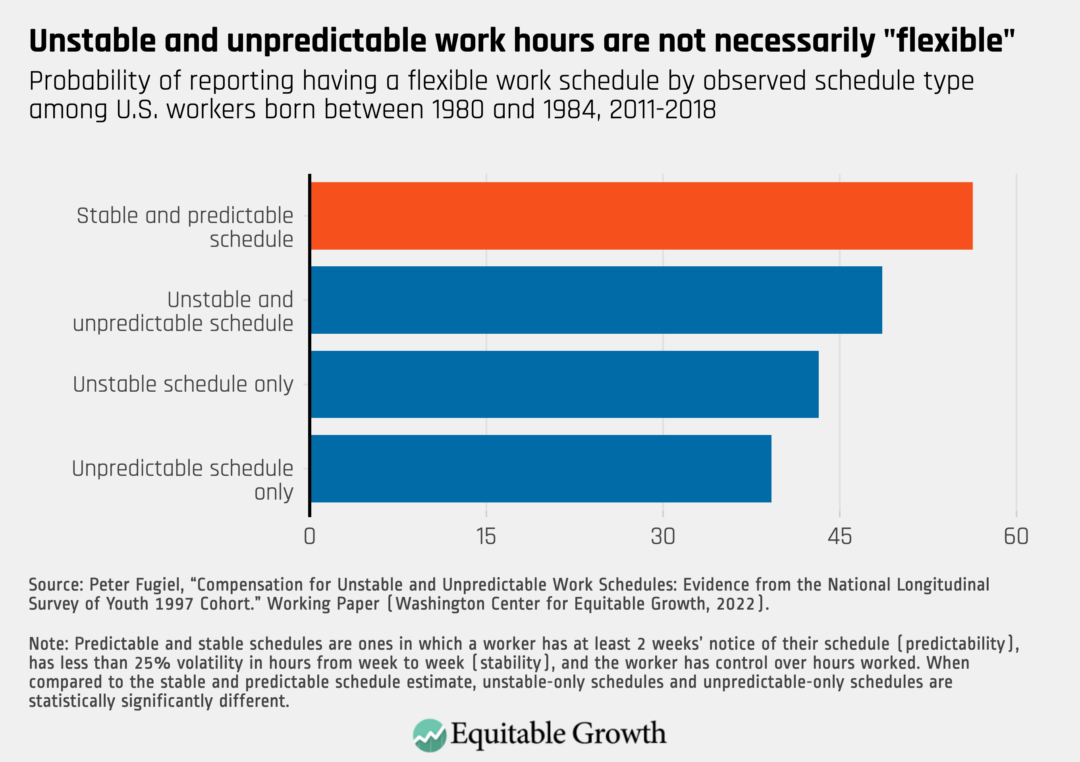

My analysis provides clear evidence that workers are worse off with scheduling risk. I find that jobs with unstable schedules offer workers no more pay and much less flexibility than otherwise-comparable jobs with stable schedules. For a typical worker with a stable and predictable schedule, the probability of having a flexible work schedule as a benefit of their job is 56 percent. That probability falls to 43 percent for those workers with an unstable schedule and 39 percent for those with an unpredictable schedule. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

I also find that scheduling risk lowers job satisfaction and reduces by 10 percentage points the probability that a worker will remain with the same employer over a period of 2 years. This negative effect on retention is consistent with prior research showing that schedule instability increases turnover at large retail and food-service firms. These results complement other recent studies calling into question whether unstable scheduling is as valuable as many employers believe. If unstable scheduling makes workers less satisfied, more likely to quit, and less productive at work, then it may not be the most efficient way of managing business risk.

Another set of findings from my working paper challenge the claim that uncompensated scheduling risk reflects the relative power of employers in the U.S. labor market. I find that compensation penalties for unstable schedules are not greater in the context of higher unemployment, where employers have more power to set compensation. Moreover, when I compare union workers and nonunion workers in the NLSY97 cohort, I find similar rates of unpredictable schedules. At least for U.S. workers in their 20s and 30s, low unemployment and a union contract are not enough to ensure fair compensation for scheduling risk.

Fair Workweek laws offer a more direct solution to the problem of schedule instability. While the details vary by jurisdiction—currently, seven cities and one state have Fair Workweek laws—these laws generally require employers to provide 2 weeks’ advance notice or extra pay for schedule changes. Research on Seattle’s scheduling regulation, for instance, found it was effective in reducing instability and improving health and economic security among covered employees.

My study strengthens the case for enacting Fair Workweek laws. I show that, on average, workers are penalized rather than rewarded for scheduling risk. Contrary to what opponents of scheduling regulations claim, unpredictable and unstable schedules lower job satisfaction and reduce flexibility for workers.

My recent research also provides a rationale for extending scheduling regulations beyond the narrow segment of retail and restaurant chains targeted by early Fair Workweek laws. Transportation and construction workers, for instance, have been largely absent from the public debate around this issue, yet they are exposed to some of the highest rates of scheduling risk.

By implementing scheduling regulations covering a wider range of workplaces across the country, policymakers can improve job quality for millions of workers. With more predictability or extra pay for schedule changes, workers will be better able to provide and care for themselves and their families.

What’s at stake is a precious resource—time—that shouldn’t be wasted with haphazard scheduling practices. If employers truly value schedule flexibility, it is only fair they compensate the workers who provide it.