New evidence shows that limiting a tax break for highly leveraged firms doesn’t hurt the U.S. economy

Does increasing taxes on businesses reduce private-sector investment? Most economists agree that investment in new projects and technologies is a key driver of economic growth. While the tax code plays less of a role in delivering true welfare-enhancing economic growth than many policymakers claim, during tax policy debates the question of which policies are most likely to increase or decrease investment nevertheless looms large over how the tax code ultimately is—or isn’t—reformed.

A new study is helping to shed light on this important question. Princeton University’s Jordan Richmond, along with the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Lucas Goodman, Adam Isen, and Matthew Smith, examine whether limiting a tax break used by highly indebted U.S. firms affects private investment and corporate debt.

The co-authors specifically investigate what is known as the 163(j) limitation on the deduction for business interest expense, which caps the amount of tax deductions firms can claim based on interest payments they make to banks and other lenders to pay off their debts. This limitation was included in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and went into effect in 2018.

While the 2017 tax law is mostly—and correctly—known for the huge tax reduction it bestows on high-income businesses and individuals, there are a few provisions that raised taxes on certain businesses in an effort to constrain the bill’s total price-tag. Section 163(j) was one such provision, which was estimated at the time to bring in $253 billion in revenue over 10 years.

In addition to helping offset the cost of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—which still increased federal debt by more than $1 trillion—the argument for including 163(j) was that U.S. companies already have a large incentive to invest in new projects via provisions such as bonus depreciation and the research and experimentation credit. Providing a preference to firms that happen to use debt to finance those projects gives them an unfair advantage over firms that choose to finance investment by selling stock or using cash on hand.

There also is a widespread concern that the more highly leveraged, debt-laden firms there are in an economy, the greater the risk of a 2009-style financial crisis, in which defaults cascade across the economy and cause a deep recession.

Limiting interest expense deductions promised to address both of these concerns. Yet, not surprisingly, U.S. businesses opposed the limitation—and continue to rail against it—claiming that it is reducing the incentive for firms to grow the U.S. economy and create jobs. Private equity firms that rely on the beneficial tax treatment of debt to make their highly leveraged business model work are particularly agitated. Progressive tax policy advocates conversely argue that the limitation is a necessary check on debt-fueled corporate raiders.

The new study by Princeton’s Richmond and his co-authors, which was presented at the National Tax Association conference earlier this month, can help policymakers make sense of the conflicting claims. The new study, titled “Tax Policy, Investment, and Firm Financing: Evidence from the U.S. Interest Limitation,” uses actual (but anonymized) tax data and sophisticated methods to compare similar firms that are differentially impacted by the policy. Specifically, they look at firms with similar levels of debt but falling above and below the firm-size threshold for the limitation, being careful to control for other tax changes that affected these firms at the same time.

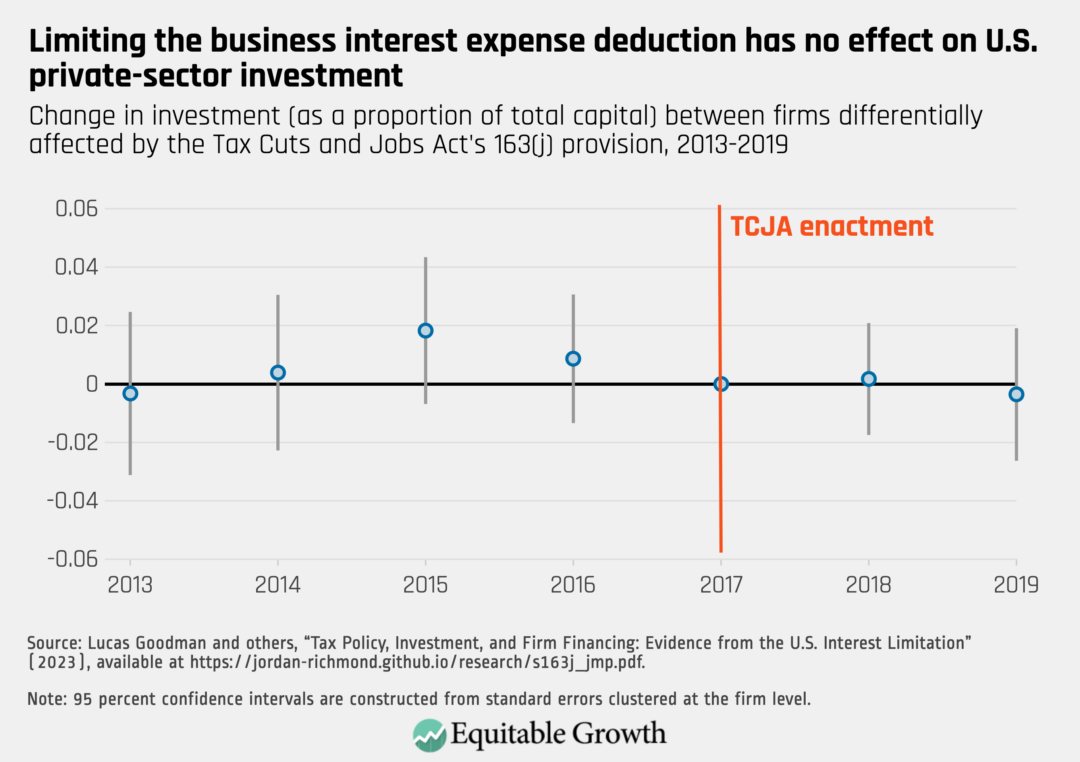

Importantly, the co-authors find that the 163(j) interest limitation did not lead to a reduction in corporate investment by the affected firms. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The co-authors also find that firms do not change their use of debt or cash financing in response to the interest limitation. These results are somewhat surprising, given the classic economic assumption that an increase in the cost of a certain type of capital—in this case, loans and other debt instruments—reduces its use. But the co-authors suggest that the lack of investment changes indicates that firms may face substantial fixed costs to adjusting their capital structures—for example, retiring long-term debt early.

Whatever the mechanism, the study’s findings indicate that limiting the interest deduction is an efficient way to raise substantial revenue. Indeed, these results help argue for doing away with the interest deduction entirely—something that leading economists and legal experts have raised as a potential component of progressive tax reform.

Yet there are three important caveats around this new paper to keep in mind. First, the study excludes utility and finance firms, including private equity funds. The former are excluded because they face rate-of-return regulation, which alters their incentives relative to other similarly debt-demanding firms and thus could bias the results. Finance firms are excluded because many of them supply rather than demand capital, which, again, would muddy the analysis. Although private equity firms themselves are excluded, the sample includes the businesses in which private equity firms invest, which are often loaded up with debt and the corresponding interest deductions.

Second, the study looks at business tax returns from 2013 to 2019, which means it does not cover 2022, when a stricter version of the limitation went into effect. The study does look at 2020 in an appendix but doesn’t fully incorporate those findings into the paper because of the unique circumstances of that year: In addition to the global COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Congress temporarily raised the interest deduction limitation in the name of further stimulating the economy.

Third, the paper’s findings diverge from that of two other papers that find significant investment reductions as a result of the deduction’s limitation. These two studies, however, use financial statement data to study the impacts of the interest limitation on a smaller set of companies, yielding less precise estimates.

Given the negligible effect overall, the findings of the new study also mean that the interest deduction limitation does not seem to be reducing systemic risk in the economy—firms are still taking out just as much debt as they have in the past. If policymakers want to more narrowly address that problem, other interventions may be more effective, such as higher capital requirements at banks.

Policymakers grappling with what to do with the interest deduction limitation—especially now that businesses and some in Congress are hoping to weaken it as part of an end-of-year tax package—should take note of this new study. Despite industry claims to the contrary, it doesn’t appear that delaying, rescinding, or loosening the limitation will boost investment in any meaningful way—just as implementing it did not hamper investment significantly.